Thesis from Parks to Presidents: Political

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

September 23 Reporting for Candidate Committees Webinar

2020 October Quarterly Reporting Webinar Candidate Committees 1 Prepared by the Federal Election Commission 2020 October Quarterly Reporting Webinar Candidate Committees REPORTING SCHEDULES & IMPORTANCE OF TIMELY FILING I. Reporting Schedule 2 Prepared by the Federal Election Commission 2020 October Quarterly Reporting Webinar Candidate Committees A. Filing frequency 1. House/Senate campaigns. Quarterly filing is mandatory for authorized campaign committees in all calendar years. 2. Presidential campaigns. Presidential campaign committees may file monthly or quarterly during non-election years. B. Election (even) year (2020) 1. Quarterly reports due April 15, July 15, October 15 and January 31. 3 Prepared by the Federal Election Commission 2020 October Quarterly Reporting Webinar Candidate Committees 2. Pre-election reports in election years. a) File Pre-Primary (or Pre-Convention or Pre-Runoff if applicable) Report due 12 days before election. For more information see https://www.fec.gov/help-candidates-and- committees/dates-and-deadlines/2020-reporting- dates/congressional-pre-election-reporting-dates-2020/ b) If participating in general election, file Pre-General Report due 12 days before general election. 3. Post-General Report, due 30 days after general election. 4 Prepared by the Federal Election Commission 2020 October Quarterly Reporting Webinar Candidate Committees 4. 48-Hour Notices a) Principal campaign committees must file for contributions of $1,000 or more received less than 20 days but more than 48 hours before 12:01am of the day of any election in which the candidate is running (even if candidate is unopposed in the election). 5 Prepared by the Federal Election Commission 2020 October Quarterly Reporting Webinar Candidate Committees b) The expedited disclosure requirements apply to all types of contributions received, including contributions collected through a joint fundraising effort. -

The Community Magazine for the High School for the Performing And

The community magazine for The High School for the Performing and Visual Arts, published by HSPVA Friends 2016-2017 Your Gift at Work: TABLE OF CONTENTS The Impact of HSPVA Friends HSPVA DOWNTOWN 4-5 Epiphany 2016-2017 As a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization, HSPVA Friends harnesses community support to ensure the ON THE COVER Charlie Wannall (‘17) in continued excellence of The High School for the Performing and Visual Arts. Under the thoughtful ART AREA HIGHLIGHTS 6-8 bobrauschenbergamerica. Photo by Savanna Lim (‘17) leadership of the Board of Directors, we create opportunities for HSPVA students that prepare them Epiphany is published annually by HSPVA Friends and for higher education and the professional world. ENCORE LUNCHEON 9 distributed to alumni, parents, and supporters of HSPVA and HSPVA Friends. HSPVA relies on us to provide the essential building blocks of an arts education—supplies, COMMUNITY NEWS 10-11 The mission of HSPVA Friends, a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization, is to cultivate support and appreciation for equipment, teachers, and experiences—that allow graduates to emerge as leaders in their The High School for the Performing and Visual Arts locally, fields. The results of an HSPVA education speak for themselves: the 166 members of the Class of 2017 nationally, and internationally in order to enhance educational, DONOR 12-15 professional, and artistic opportunities for current and future were offered more than $36 million in college scholarships! students of HSPVA. RECOGNITION I am delighted to share highlights from HSPVA’s 45th school year. Thanks to your generosity, HSPVA HSPVA FRIENDS BOARD OF DIRECTORS Robert L. -

Wells College Association of Alumnae and Alumni

WellsNotes Spring 2020 Wells College Alumnae and Alumni Newsletter Wells College Association of Alumnae and Alumni WCA TO HONOR TWO DISTINGUISHED ALUMNAE THIS MAY The Wells College Association of Alumnae and Alumni (WCA) is proud to announce the two recipients of the 2020 WCA Award: Gwen Wilkinson ’77 and Stephanie Batcheller ’79. Both alumnae have had distinguished careers in the field of law with a particular emphasis on public service: Gwen as a district attorney and social justice advocate, and Stephanie as a public defender and legal educator. GWEN WILKINSON ’77 STEPHANIE BATCHELLER ’79 The Wells College Association of Alumnae The Wells College Association of Alumnae and Alumni is honoring Gwen Wilkinson and Alumni is honoring Stephanie ’77 with the WCA Award in recognition Batcheller ’79 with the WCA Award for of her public service, especially in the her accomplishments in the field of law and prosecution of perpetrators of child abuse contributions to the justice system. and domestic violence and in addressing Stephanie, a career public defender who has other social justice issues. argued before courts in Georgia, Maryland Gwen established herself as a proactive, and New York, is a senior staff attorney with ethical and passionate advocate for social the New York State Defenders Association justice throughout her career as a prosecutor (NYSDA). Since 1998, she has been with the and social services attorney in Tompkins association’s nonprofit Public Defense Backup County, N.Y. Those same attributes define her work with community Center, where she serves as senior staff attorney, developing client- organizations, providing context for how her education at Wells framed centered representation training strategies for new public defense the passion and drive she is known for. -

Successful Communication in the Workplace 1

Successful Communication in the Workplace 1 Leslie Knope of Parks and Recreation: Successful Communication in the Workplace November 28, 2016 Leslie Knope 2 Introduction According to Genderlect Styles, a theory by Deborah Tannen, women traditionally communicate for relationship while men communicate for power. In order to work past oppression in the workplace, women have had to adjust their communication style to communicate for power vs. relationship, but often receive negative attention for it. Are male communication styles for power the only way to gain success in the workplace today? The television show, Parks and Recreation, shows a good example of a character, Leslie Knope, who exemplifies both types of communication: communicating for power and relationship. She takes a lot of time to invest in her friends and usually, as a comedic element of the series, wants everyone to like her and everyone to be happy, but this usually causes more harm than good. She learns throughout the series that her success comes from her care for her friends and her town while commanding power to stand out as a leader in order to rise in politics. Can success only be gained when we communicate for power instead of relationships? I will look to answer the question of how television series, films, and the media depict “successful” communication practices for women in the workplace by analyzing the character of Leslie Knope in Parks and Recreation. My literature review will discuss how the media portrays women, and what truth these depictions hold for women in the working world. Literature Review A large portion of research done on this topic discusses how prominent female roles in our media are scrutinized, and how positive female roles of women in power are generally underrepresented. -

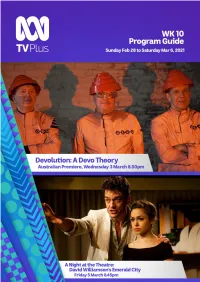

ABC Kids/ABC TV Plus Program Guide: Week 10 Index

1 | P a g e ABC Kids/ABC TV Plus Program Guide: Week 10 Index Index Sunday, 28 February 2021 .................................................................................................................................... 3 Monday, 1 March 2021 ......................................................................................................................................... 9 Tuesday, 2 March 2021 ....................................................................................................................................... 15 Wednesday, 3 March 2021 ................................................................................................................................. 21 Thursday, 4 March 2021 ..................................................................................................................................... 27 Friday, 5 March 2021 .......................................................................................................................................... 33 Saturday, 6 March 2021 ...................................................................................................................................... 38 NOTE: Program times may differ in some states if viewing on VAST or Foxtel. More information can be found at ABC Help. 2 | P a g e ABC Kids/ABC TV Plus Program Guide: Week 10 Sunday, 28 February 2021 Program Guide Sunday, 28 February 2021 5:00am The Day Henry Met (Repeat,G) 5:05am Little Princess (CC,Repeat,G) 5:20am Sarah And Duck (Repeat,G) 5:25am Hoot Hoot Go! (CC,Repeat,G) -

Amy Poehler, Sarah Silverman, Aziz Ansari and More on the Lost Comic

‘He was basically the funniest person I ever met’ Amy Poehler, Sarah Silverman, Aziz Ansari and more on the lost comic genius of Harris Wittels By Hadley Freeman Monday 17.04.17 12A Quiz Fingersh Pit your wits against the breakout stars of this year’s University Challenge, and Bobby Seagull , with Eric Monkman 20 questions set by the brainy duo. No conferring The Fields Medal has in secutive order. This spells out the 5 1 recent times been awarded name of which London borough? to its fi rst woman, Maryam Mirzakhani in 2014, and was What links these former infamously rejected by Russian 7 prime minsters: the British Grigori Perelman in 2006. Which Spencer Perceval, the Lebanese academic discipline is this prize Rafi c Hariri and the Indian awarded for? Indira Gandhi? Whose art exhibition at Tate Narnia author CS Lewis, 2 Britain this year has become 8 Brave New World author the fastest selling show in the Aldous Huxley and former US gallery’s history? president John F Kennedy all died on 22 November. Which year The fi rst national park desig- was this? 3 nated in the UK was the Peak District in 1951. Announced as a Which north European national park in 2009 and formed 9 country’s fl ag is the oldest in 2010, which is the latest existing fl ag in the world? It is English addition to this list? 15 supposed to have fallen out of the heavens during a battle in the University Challenge inspired 13th century. 4 the novel Starter for Ten. -

Fife Lake Public Library a Member of Traverse Area District Library Features September 2019

Fife Lake Public Library A Member of Traverse Area District Library Features September 2019 Information and Hours 77 Lakecrest Lane Fife Lake, MI 49633 Phone: 231-879-4101 Let us help you have a successful Fax: 231-879-3360 [email protected] school year! Sun. & Mon.: Closed We have free public Wi-Fi, public computers, and Tues. & Thurs.: 9am-7pm MELcat resources: ebook text books, practice ACT/ Wed. & Fri.: 9am-5pm Saturday: 10am-2pm SAT tests, Britannica - Online Encyclopedia, Read it- helps to build reading skills and improve Library Resources study habits, and Novelist - Find just the right book Books on Every Subject by subject, age, awards won, books made into Fitness Programs movies, and much more! Volunteer Opportunities Programs for All Ages Early Literacy Blood Drive Tot Time Yoga Luncheons Community Calendar Technology Friends Christmas Tea Wifi Summer Reading Glass Buffet Plate and Cup Sets Coffee Movies Available at Chris Seeley’s Garage Sale Audio Books during Labor Day weekend. Fun, Fun, Fun! August 30 - September 1 All proceeds of the tea set sales will be donated to the Friends of the Fife Lake Public Library. Book Page September 2019 Outfox A Better Man By Sandra Brown By Louise Penny Chances Are Contraband By Richard Russo By Stuart Woods The Chelsea Girls The Dark Side By Fiona Davis By Danielle Steele Good Girl, Bad Girl Ellie and the Harpmaker By Michael Robotham By Hazel Prior If you like… Try ... Tues. Sep 17 Tues. Nov 19 Jimmy Quinn The Light Over London By Richard VanDeWeghe By Julia Kelly Tues. Oct 15 Tues. -

En Genusmedveten Analys Av Varför Remaken Ghostbusters Blivit Hatad

Örebro Universitet Institutionen för humaniora, utbildning och samhällsvetenskap En genusmedveten analys av varför remaken Ghostbusters blivit hatad Självständigt arbete 15hp 2017-01-12 Medie- och kommunikationsvetenskap med inriktning film Handledare: Anne Bachmann Författare: Linnea Hamrin & Amanda Holmstedt Abstract This essay is about the hate Ghostbusters (2016) has received. To find out why the film is hated, a reception study has been done. YouTube and IMDb are the two websites used in this study to collect the hate-comments and reviews. Ghostbusters (2016) is a remake of the original film with the same name from 1984, the original solely has men in the main roles. A big difference between the two films is that the remake contains women instead of men in the main roles. The trailer of Ghostbusters (2016) got many “downvotes” on YouTube and there after the hatred streamed in. Why is the film hated? The theories used in this study contains subjects of representation, attraction and fat studies. As a method Stuart Hall’s Encoding/decoding was used to analyze the reception of the film. This essay contains content which can be connected to cultural studies and feminism. Keywords: Ghostbusters, cultural studies, feminism, gender studies, encoding/decoding, hate speech, fat studies Innehållsförteckning: 1. Inledning 1 1.1 Bakgrund 2 1.2 Syfte 4 1.3 Avgränsningar 4 2. Tidigare forskning 6 3. Teoretiska utgångspunkter 8 3.1 Representation 9 3.2 Attraktion 10 3.3 Fat studies 11 4. Material och metod 13 4.1 Urval och material 13 4.2 Metod 14 4.2.1 Encoding/decoding 15 4.2.2 Susan Faludi 17 4.3 Metodproblem 18 5. -

TELEVISION NOMINEES DRAMA SERIES Breaking Bad, Written By

TELEVISION NOMINEES DRAMA SERIES Breaking Bad, Written by Sam Catlin, Vince Gilligan, Peter Gould, Gennifer Hutchison, George Mastras, Thomas Schnauz, Moira Walley-Beckett; AMC The Good Wife, Written by Meredith Averill, Leonard Dick, Keith Eisner, Jacqueline Hoyt, Ted Humphrey, Michelle King, Robert King, Erica Shelton Kodish, Matthew Montoya, J.C. Nolan, Luke Schelhaas, Nichelle Tramble Spellman, Craig Turk, Julie Wolfe; CBS Homeland, Written by Henry Bromell, William E. Bromell, Alexander Cary, Alex Gansa, Howard Gordon, Barbara Hall, Patrick Harbinson, Chip Johannessen, Meredith Stiehm, Charlotte Stoudt, James Yoshimura; Showtime House Of Cards, Written by Kate Barnow, Rick Cleveland, Sam R. Forman, Gina Gionfriddo, Keith Huff, Sarah Treem, Beau Willimon; Netflix Mad Men, Written by Lisa Albert, Semi Chellas, Jason Grote, Jonathan Igla, Andre Jacquemetton, Maria Jacquemetton, Janet Leahy, Erin Levy, Michael Saltzman, Tom Smuts, Matthew Weiner, Carly Wray; AMC COMEDY SERIES 30 Rock, Written by Jack Burditt, Robert Carlock, Tom Ceraulo, Luke Del Tredici, Tina Fey, Lang Fisher, Matt Hubbard, Colleen McGuinness, Sam Means, Dylan Morgan, Nina Pedrad, Josh Siegal, Tracey Wigfield; NBC Modern Family, Written by Paul Corrigan, Bianca Douglas, Megan Ganz, Abraham Higginbotham, Ben Karlin, Elaine Ko, Steven Levitan, Christopher Lloyd, Dan O’Shannon, Jeffrey Richman, Audra Sielaff, Emily Spivey, Brad Walsh, Bill Wrubel, Danny Zuker; ABC Parks And Recreation, Written by Megan Amram, Donick Cary, Greg Daniels, Nate DiMeo, Emma Fletcher, Rachna -

Historic Context Study of Waterfowl Hunting Camps and Related Properties Within Assateague Island National Seashore, Maryland and Virginia

Historic Context Study of Waterfowl Hunting Camps and Related Properties within Assateague Island National Seashore, Maryland and Virginia by Ralph E. Eshelman, Ph.D and Patricia A. Russell Eshelman & Associates July 21, 2004 For Assateague Island National Seashore National Park Service Department of Interior 7206 National Seashore Lane Berlin, Maryland 21811 i ii CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS…………………………………………………………. ii ABSTRACT………………………………………………………………………..iii INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………………………..1 Project background Clubs and lodges Definitions Regional context WATERFOWL HUNTING ON THE ATLANTIC ………………………………..7 Delaware North to New York Maryland Virginia North Carolina South to Georgia Assateague Island WATERFOWL HUNTING CLUBS AND LODGES……………………………..21 Land-Based Facilities Water-Based Facilities TYPICAL DAY AT A WATERFOWL HUNTING CLUB……………………….31 SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC ASPECTS OF WATERFOWL HUNTING CLUBS AND LODGES………………………………………………… 33 Owners Members Guests: The Rich and Famous Gender Guides Food Thrill of the Hunt Fraternal Comradeship Ethnicity of Support Staff Role in Conservation ASSATEGUE ISLAND WATERFOWL HUNTING CAMPS AND LODGES…………………………………………………………………..47 ASSOCIATED PHYSICAL CHARACTERISTICS OF ASSATEGUE ISLAND WATERFOWL HUNTING CLUBS AND LODGES………….49 iii INVENTORY OF RESOURCES…………………………………………………52 Bob-O-Del Gun Club Bunting’s Gunning Lodge Clements’ Beach House Clements’ Boat House Green Run Lodge High Winds Gun Club Hungerford’s Musser’s Peoples & Lynch Pope’s Island Gun Club Valentine’s CONCLUSION……………………………………………………………………72 REFERENCES CITED……………………………………………………………76 APPENDIX I ANNOTATED LIST OF GUN CLUBS AND LODGES IN MARYLAND AND VIRGINIA………………………………………90 APPENDIX II PROFESSIONAL TRAINING AND EXPERIENCE OF CONTEXT STUDY TEAM………………………………………………99 APPENDIX III CULTURAL LANDSCAPE FIELD SURVEY…………………………………100 iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This project benefited from numerous persons who assisted us in countless ways, shared knowledge, and otherwise made this study possible. -

Television Academy

Television Academy 2014 Primetime Emmy Awards Ballot Outstanding Directing For A Comedy Series For a single episode of a comedy series. Emmy(s) to director(s). VOTE FOR NO MORE THAN FIVE achievements in this category that you have seen and feel are worthy of nomination. (More than five votes in this category will void all votes in this category.) 001 About A Boy Pilot February 22, 2014 Will Freeman is single, unemployed and loving it. But when Fiona, a needy, single mom and her oddly charming 11-year-old son, Marcus, move in next door, his perfect life is about to hit a major snag. Jon Favreau, Director 002 About A Boy About A Rib Chute May 20, 2014 Will is completely heartbroken when Sam receives a job opportunity she can’t refuse in New York, prompting Fiona and Marcus to try their best to comfort him. With her absence weighing on his mind, Will turns to Andy for his sage advice in figuring out how to best move forward. Lawrence Trilling, Directed by 003 About A Boy About A Slopmaster April 15, 2014 Will throws an afternoon margarita party; Fiona runs a school project for Marcus' class; Marcus learns a hard lesson about the value of money. Jeffrey L. Melman, Directed by 004 Alpha House In The Saddle January 10, 2014 When another senator dies unexpectedly, Gil John is asked to organize the funeral arrangements. Louis wins the Nevada primary but Robert has to face off in a Pennsylvania debate to cool the competition. Clark Johnson, Directed by 1 Television Academy 2014 Primetime Emmy Awards Ballot Outstanding Directing For A Comedy Series For a single episode of a comedy series. -

2012 Annual Report

2012 ANNUAL REPORT Table of Contents Letter from the President & CEO ......................................................................................................................5 About The Paley Center for Media ................................................................................................................... 7 Board Lists Board of Trustees ........................................................................................................................................8 Los Angeles Board of Governors ................................................................................................................ 10 Public Programs Media As Community Events ......................................................................................................................14 INSIDEMEDIA/ONSTAGE Events ................................................................................................................15 PALEYDOCFEST ......................................................................................................................................20 PALEYFEST: Fall TV Preview Parties ...........................................................................................................21 PALEYFEST: William S. Paley Television Festival ......................................................................................... 22 Special Screenings .................................................................................................................................... 23 Robert M.