Title 2—Appendix

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Dischargeability of Debts in Bankruptcy

Vanderbilt Law Review Volume 15 Issue 1 Issue 1 - December 1961 Article 2 12-1961 The Dischargeability of Debts in Bankruptcy Paul I. Hartman Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/vlr Part of the Bankruptcy Law Commons Recommended Citation Paul I. Hartman, The Dischargeability of Debts in Bankruptcy, 15 Vanderbilt Law Review 13 (1961) Available at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/vlr/vol15/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Vanderbilt Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Dischargeability of Debts in Bankruptcy Paul I. Hartman* To many debtors, the discharge is the raison d'etre of the bankruptcy laws. In this article, Professor Hartman discusses the history of the dis- charge, its availability and application in certain situations, and its per- sonal nature. I. INThODUCrION From the viewpoint of the bankrupt debtor, a discharge from his obliga- tions is, no doubt, the most important facet of bankruptcy proceedings. The bankruptcy discharge is designed to relieve the honest debtor from his financial entanglements, and to give him an opportunity to reinstate him- self in the business world.' A debtor is now entitled to a discharge as a matter of right, unless he has been guilty of certain specified offenses against the Bankruptcy Act.2 For many generations the idea of a discharge from one's debts has been the relieving feature of bankruptcy. However, it has not always been so. -

Of Iowa Code

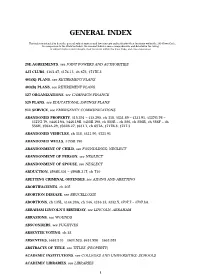

GENERAL INDEX This index is intended to describe general subject matters and law concepts and to identify their locations within the 2014 Iowa Code. In comparison to the Skeleton Index, the General Index is more comprehensive and detailed in the listing of subject matters and concepts, their locations within the Iowa Code, and cross-references. 28E AGREEMENTS, see JOINT POWERS AND AUTHORITIES 4-H CLUBS, §163.47, §174.13, ch 673, §717E.3 401(K) PLANS, see RETIREMENT PLANS 403(B) PLANS, see RETIREMENT PLANS 527 ORGANIZATIONS, see CAMPAIGN FINANCE 529 PLANS, see EDUCATIONAL SAVINGS PLANS 911 SERVICE, see EMERGENCY COMMUNICATIONS ABANDONED PROPERTY, §15.291 – §15.295, ch 318, §321.89 – §321.91, §327G.76 – §327G.79, §446.19A, §446.19B, §455B.190, ch 555B – ch 556, ch 556B, ch 556F – ch 556H, §562A.29, §562B.27, §631.1, ch 657A, §717B.8, §727.3 ABANDONED VEHICLES, ch 318, §321.90, §321.91 ABANDONED WELLS, §455B.190 ABANDONMENT OF CHILD, see FOUNDLINGS; NEGLECT ABANDONMENT OF PERSON, see NEGLECT ABANDONMENT OF SPOUSE, see NEGLECT ABDUCTION, §598B.301 – §598B.317, ch 710 ABETTING CRIMINAL OFFENSES, see AIDING AND ABETTING ABORTIFACIENTS, ch 205 ABORTION DISEASE, see BRUCELLOSIS ABORTIONS, ch 135L, §144.29A, ch 146, §216.13, §232.5, §707.7 – §707.8A ABRAHAM LINCOLN’S BIRTHDAY, see LINCOLN, ABRAHAM ABRASIONS, see WOUNDS ABSCONDERS, see FUGITIVES ABSENTEE VOTING, ch 53 ABSENTEES, §633.510 – §633.520, §633.580 – §633.585 ABSTRACTS OF TITLE, see TITLES (PROPERTY) ACADEMIC INSTITUTIONS, see COLLEGES AND UNIVERSITIES; SCHOOLS ACADEMIC LIBRARIES, see -

TITLE STANDARDS October 10, 2019 10305 ICLE: State Bar Series

TITLE STANDARDS October 10, 2019 10305 ICLE: State Bar Series Thursday, October 10, 2019 TITLE STANDARDS 6 CLE Hours Including 1 Ethics Hour | 1 Professionalism Hour Copyright © 2019 by the Institute of Continuing Legal Education of the State Bar of Georgia. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic, mechanical photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of ICLE. The Institute of Continuing Legal Education’s publications are intended to provide current and accurate information on designated subject matter. They are off ered as an aid to practicing attorneys to help them maintain professional competence with the understanding that the publisher is not rendering legal, accounting, or other professional advice. Attorneys should not rely solely on ICLE publications. Attorneys should research original and current sources of authority and take any other measures that are necessary and appropriate to ensure that they are in compliance with the pertinent rules of professional conduct for their jurisdiction. ICLE gratefully acknowledges the eff orts of the faculty in the preparation of this publication and the presentation of information on their designated subjects at the seminar. The opinions expressed by the faculty in their papers and presentations are their own and do not necessarily refl ect the opinions of the Institute of Continuing Legal Education, its offi cers, or employees. The faculty is not engaged in rendering legal or other professional advice and this publication is not a substitute for the advice of an attorney. -

Mississippi Title Examination Standards

MISSISSIPPI TITLE EXAMINATION STANDARDS SECOND EDITION (Originally adopted effective as of August 1, 2019; Updated effective as of August 1, 2021) Copyright © 2021 Real Property Section of The Mississippi Bar All rights reserved. No copyright is claimed in the text of statutes, regulations, rules, and excerpts from court opinions quoted within this work. FOREWORD Background In 2018, the Executive Committee of the Real Property Section of The Mississippi Bar (the “Section”) approved the formation of a committee to study the formulation and development of title examination standards. After a great deal of study of the use of title examination standards in other states and many hours of drafting and meeting time, the committee (the “Title Standards Board” or “Board”), proposed the first Mississippi title examination standards, which were approved by the Section at The Mississippi Bar Annual Meeting on July 12, 2019, as the first Mississippi title examination standards (the “Standards”). The Board will meet as needed to consider additional standards, amendments to existing standards, and commentary. Amendments and new standards will be presented to the membership of the Section prior to formal adoption by the Section. The Board itself will make changes to the comments and cautions as needed. The Board welcomes comments and suggestions, which may be submitted to the Section chair. Purpose The Standards are guidelines intended to assist land title attorneys (hereinafter referred to as “title examiners” or as an “examiner”) called upon to assess the marketability of land titles, focusing on the manner in which a prudent examiner approaches matters that may be encountered during the course of an examination. -

(2007-165) 2007 Vt

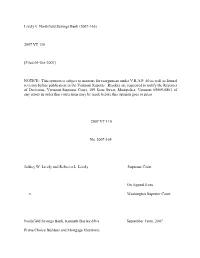

Lively v. Northfield Savings Bank (2007-165) 2007 VT 110 [Filed 05-Oct-2007] NOTICE: This opinion is subject to motions for reargument under V.R.A.P. 40 as well as formal revision before publication in the Vermont Reports. Readers are requested to notify the Reporter of Decisions, Vermont Supreme Court, 109 State Street, Montpelier, Vermont 05609-0801 of any errors in order that corrections may be made before this opinion goes to press. 2007 VT 110 No. 2007-165 Jeffrey W. Lively and Rebecca L. Lively Supreme Court On Appeal from v. Washington Superior Court Northfield Savings Bank, Kenneth Bayley d/b/a September Term, 2007 Prime Choice Builders and Mortgage Electronic Registration Systems, Inc. Mary Miles Teachout, J. William L. Durrell of Benjamin, Bookchin & Durrell, P.C., Montpelier, for Plaintiffs-Appellants. Chad V. Bonanni of Bergeron, Paradis & Fitzpatrick, LLP, Essex Junction, for Defendant- Appellee Mortgage Electronic Registration Systems, Inc. PRESENT: Reiber, C.J., Dooley, Johnson, Skoglund and Burgess, JJ. ¶ 1. DOOLEY, J. In this judgment-lien-foreclosure action, the plaintiffs, Jeffrey and Rebecca Lively, challenge a decision of the superior court, granting summary judgment to defendant, Mortgage Electronic Registration Systems, Inc. (MERS). The court concluded that plaintiffs had failed to perfect their judgment lien against debtor, Kenneth Bayley, because the court issuing the judgment misspelled debtor’s surname and failed to include in the judgment order the date on which the judgment became final. The superior court also determined that, even if the judgment lien was enforceable against debtor’s property, the lien was junior to defendant’s security interest, because at the time the judgment was recorded, debtor and his former wife held the property at issue as tenants by the entirety. -

Title Examinations and Title Issues

CHAPTER 7 Title Examinations and Title Issues R. Prescott Jaunich, Esq. Downs Rachlin Martin PLLC, Burlington Timothy S. Sampson, Esq. Downs Rachlin Martin PLLC, Burlington § 7.1 Introduction ................................................................................. 7–1 § 7.2 Marketable Title .......................................................................... 7–4 § 7.2.1 Vermont Title Standards ............................................... 7–4 § 7.2.2 Common Law Marketable Title—Permits as Encumbrances ............................................................... 7–6 § 7.2.3 Vermont Marketable Record Title Act ........................ 7–10 (a) Person ................................................................ 7–11 (b) Unbroken Chain of Title .................................... 7–11 (c) Conveyance ....................................................... 7–12 (d) Preserved Claims Under the Act ........................ 7–13 § 7.3 Conveyancing Requirements .................................................... 7–15 § 7.3.1 Vermont Deed Customs .............................................. 7–15 § 7.3.2 Deeds by Trustees and Deeds to Trust ........................ 7–17 § 7.3.3 Deeds by Executors, Administrators and Guardians .. 7–17 § 7.3.4 Deeds by Divorce Judgment ....................................... 7–18 § 7.3.5 Probate Decree ............................................................ 7–18 § 7.4 Identifying the Real Estate and Property Descriptions .......... 7–18 § 7.4.1 Reference to Prior Deeds and Instruments -

Update on Oklahoma Real Property Title Authority: Statutes, Regulations, Cases, Attorney General Opinions & Title Examination Standards: Revisions for 2009-2010

UPDATE ON OKLAHOMA REAL PROPERTY TITLE AUTHORITY: STATUTES, REGULATIONS, CASES, ATTORNEY GENERAL OPINIONS & TITLE EXAMINATION STANDARDS: REVISIONS FOR 2009-2010 (Covering July 1, 2009 to June 30, 2010) BY: KRAETTLI Q. EPPERSON, PLLC MEE MEE HOGE & EPPERSON, PLLP 50 PENN PLACE 1900 N.W. EXPRESSWAY, SUITE 1400 OKLAHOMA CITY, OKLAHOMA 73118 PHONE: (405) 848-9100 FAX: (405) 848-9101 E-mail: [email protected] Webpages: www.meehoge.com www.EppersonLaw.com Presented For the: 2011 CLEVERDON ROUNDTABLE SEMINAR OKLAHOMA BAR ASSOCIATION REAL PROPERTY LAW SECTION At Tulsa, OK: May 6, 2011 Oklahoma City, OK: May 13, 2011 (C:\mydocuments\bar&papers\papers\240tleUpdate(09-10)(RPLS).doc) 1 KRAETTLI Q. EPPERSON, PLLC ATTORNEY AT LAW POSITION: Partner: Mee Mee Hoge & Epperson, PLLP 1900 N.W. Expressway, Suite 1400, Oklahoma City, OK 73118 Voice: (405) 848-9100; Fax: (405) 848-9101 E-mail: [email protected]; website: www.EppersonLaw.com COURTS: Okla. Sup. Ct. (May 1979); U.S. Dist. Ct., West. Dist of Okla. (Dec. 1984) EDUCATION: University of Oklahoma [B.A. (PoliSci-Urban Admin.) 1971]; State Univ. of N.Y. at Stony Brook [M.S. (Urban and Policy Sciences) 1974]; & Oklahoma City University [J.D. (Law) 1978]. PRACTICE: Oil/Gas & Real Property Litigation (Arbitration, Shared Surface Use, Quiet Title, Condemnation, & Restrictions); Condo/HOA Creation & Representation; and Commercial Real Estate Acquisition & Development. MEMBERSHIPS/POSITIONS: OBA Title Examination Standards Committee (Chairperson: 1992-Present); OBA Nat’l T.E.S. Resource Center (Director: 1989 -

California Style Manual

CALIFORNIA STYLE MANUAL Fourth Edition A HANDBOOK OF LEGAL STYLE FOR CALIFORNIA COURTS AND LAWYERS By Edward W. Jessen Reporter of Decisions for the Supreme Court and Courts of Appeal .W4-23370-9 ©1942, 1961, 1977, 1986,2000 by the Supreme Court of California Page composition by Imagelnk, San Francisco Cover design by Side by Side Designs, San Francisco Editiorial preparation and manufacturing West Group, California's Official Legal Publisher FOREWORD For almost 60 years, the legal community of California has benefited from the publication of the California Style Manual. The manual provides a guide to standard legal style in the appellate courts, and benefits litigants and jurists alike by establishing a common stylistic base that permits read- ers to focus readily on substance rather than form. In the 14 years since publication of the third edition of the Style Manual, much has changed in the processes used for creating legal docu- ments. A personal computer on the desk is now the rule rather than the exception for most lawyers and judges. At the same time, the availability of diverse reference resources has expanded the ease and scope of research. This latest revision of the manual reflects and responds to many of the changes that the legal profession has experienced, while maintaining a steady hold on the practices that have served the courts and the profession so well. I extend my appreciation to the Reporter of Decisions and those who have assisted him in the task of revising this valuable reference tool. Ronald M. George Chief Justice of California iii SUPREME COURT APPROVAL To the Reporter of Decisions: Pursuant to the authority conferred on the Supreme Court of Cali- fornia by Government Code section 68902, the California Style Manual, Fourth Edition, as submitted to this court for review is approved and adopted as the official organ for the styles to be used in the publication of the Official Reports. -

Tx Vern Stat Property V1 2013 Pp Bk

Vernon’s TEXAS CODES ANNOTATED Volume 1 PROPERTY CODE Sections 1.001 to 21.040 2013 Cumulative Annual Pocket Part Replacing 2012 pocket part supplementing 2004 main volume For Use In 2013–2014 Includes Laws through the 2013 Third Called Session of the 83rd Legislature Mat #41465166 128 a 2013 Thomson Reuters This publication was created to provide you with accurate and authoritative information concerning the subject matter covered; however, this publication was not necessarily prepared by persons licensed to practice law in a particular jurisdiction. The publisher is not engaged in rendering legal or other professional advice and this publication is not a substitute for the advice of an attorney. If you require legal or other expert advice, you should seek the services of a competent attorney or other professional. West’s and Westlaw are registered in the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office. VERNON’S is registered in the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office. TITLE 2—APPENDIX TEXAS TITLE EXAMINATION STANDARDS For easier reference, the Title Examination Standards appear in their entirety in the pocket part of V.T.C.A., Property Code, vol. 1. As Initially Adopted by the Section of Real Estate, Probate and Trust Law and the Oil, Gas and Energy Resources Law Section of the State Bar of Texas on June 27, 1997, as revised through August 2, 2013. By THE TITLE STANDARDS JOINT EDITORIAL BOARD OF THE SECTION OF REAL ESTATE, PROBATE AND TRUST LAW AND THE OIL, GAS AND ENERGY RESOURCES LAW SECTION OF THE STATE BAR OF TEXAS Executive Editor: Edward H. -

IN the COURT of APPEALS of MARYLAND No

Circuit Court for Baltimore County Case # 93CV3985 IN THE COURT OF APPEALS OF MARYLAND No. 48 September Term, 1999 GARY W. WAICKER et al. v. FABIO K. BANEGURA et al. Bell, C. J. Eldridge Rodowsky Raker Wilner Cathell Harrell, - JJ. Opinion by Cathell, J. Filed: February 9, 2000 Gary W. Waicker and Diane L. Waicker, appellants, appeal from a judgment of the Circuit Court for Baltimore County, in favor of Mystic Investments, Inc. (Mystic or Mystic Investments), appellee, finding that Mystic’s lien had priority over a misindexed lien of appellants.1 Appellants present one issue: “Whether the judgment held by appellants Gary and Diane Waicker has priority over the judgments to which appellee Mystic Investments, Inc., have been subrogated.” We respond to appellants’ issue in the negative, and accordingly affirm the circuit court. I. Facts On or about April 28, 1993, appellants, Gary W. Waicker and Diane L. Waicker, sought to have a deficiency judgment they held from the Circuit Court for Baltimore City against appellees Fabio K. Banegura and Olive K. Banegura, as husband and wife, recorded in the Circuit Court for Baltimore County. When the Waickers’ judgment was indexed and recorded by the Clerk of the Baltimore County Circuit Court, it was misindexed under the name Baneguna rather than Banegura. The Baltimore County Notice of Recordation, dated April 28, 1993, was mailed to appellants and showed that the judgment had been indexed improperly.2 1 On our own motion, we issued a writ of certiorari prior to consideration by the Court of Special Appeals. 2 The docket entries in respect to the underlying deficiency judgment rendered in the Circuit Court for Baltimore City include this entry: 02/19/93 ORDR DECREE-JUDGMENT ENTERED IN FAVOR OF GARY W. -

IN the COURT of APPEALS of TENNESSEE at KNOXVILLE May 23, 2006 Session

IN THE COURT OF APPEALS OF TENNESSEE AT KNOXVILLE May 23, 2006 Session BILL YOUNG and wife, MARY YOUNG v. RAC EXPRESS, INC., WILLIAM HAMBLIN & TOMMY HEATWOLE (a/k/a TOMMY HEATWOLD, JR. Direct Appeal from the Chancery Court for Campbell County No. 03-213 Hon. Billy Joe White, Chancellor No. E2005-01165-COA-R3-CV - FILED JUNE 21, 2006 In this declaratory judgment action, the Trial Court invalidated a judgment lien on plaintiffs’ property. On appeal, we affirm. Tenn. R. App. P.3 Appeal as of Right; Judgment of the Chancery Court Affirmed. HERSCHEL PICKENS FRANKS, P.J., delivered the opinion of the court, in which D. MICHAEL SWINEY, J., and SHARON G. LEE, J., joined. Stanley F. Roden, Knoxville, Tennessee, for appellant. Johnny V. Dunaway, Lafollette, Tennessee, for appellees. OPINION Plaintiffs brought this action against RAC Express, Inc., William Hamblin and Tommy Heatwole (a/k/a Tommy Heatwold, Jr.), alleging plaintiffs owned certain real property in Campbell County which they acquired via warranty deed from Hamblin on April 25, 2003, and which Hamblin had acquired from Heatwold via warranty deed on August 15, 2002. Plaintiffs further alleged that they had tried to obtain a loan using the real property as collateral, and that a title search revealed there was a judgment lien outstanding in favor of RAC Express, Inc., against Heatwold. Plaintiffs alleged that the judgment was entered on August 6, 2000, in the amount of $14,000.00, and was recorded as a lien against real property owned by Heatwold on February 21, 2001. Further, that the judgment lien was invalid and had not been properly perfected, and the property was not subject to same. -

Legal Terminology Definitions Latin Terms

Legal Terminology Definitions Latin Terms: a fortiori - With stronger reason a priori - From the cause to the effect ab initio - From the beginning actiones in personam - Personal actions ad curiam - Before a court; to court ad damnum clause - To the damage, clause in a complaint stating monetary loss ad faciendum - To do ad hoc - For this purpose or occasion ad litem - For this suit or litigation ad rem - To the thing at hand ad valorem - According to the value adversus - Against aggregatio menium - Contractual meeting of the minds alias dictus - An assumed name alibi - In another place, elsewhere aliunde - From another place, from without (as in evidence outside the document) alter ego - The other self amicus curiae - “friend of the court” brief animo - With intention, disposit ion, design or will animus - Mind or intention ante litem motam - before the suit or before litigation is filed arguendo - In the course of an argument assumpsit - He undertook or promised bona fide - Good faith capias - Take, arrest captia - Persons, or heads causa mortis - By reason of death caveat - Beware, a warning caveat emptor - “Let the buyer beware” certiorari - “send the pleadings up”, indicating a discretionary review process Cestui - Beneficiaries Cestui que trust - Beneficiaries of a trust circa - In the area of, about or concerning compos mentis - Of sound mind consortium - The conjugal fellowship of husband and wife contra - Against coram nobis - Before us ourselves corpus - Body corpus delicti - Body of the offense cum testamento annexo - “With