Archaeology and Community in Athienou, Cyprus P

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pyla-Koutsopetria I Archaeological Survey of an Ancient Coastal Town American Schools of Oriental Research Archeological Reports

PYLA-KOUTSOPETRIA I ARCHAEOLOGICAL SURVEY OF AN ANCIENT COASTAL TOWN AMERICAN SCHOOLS OF ORIENTAL RESEARCH ARCHEOLOGICAL REPORTS Kevin M. McGeough, Editor Number 21 Pyla-Koutsopetria I: Archaeological Survey of an Ancient Coastal Town PYLA-KOUTSOPETRIA I ARCHAEOLOGICAL SURVEY OF AN ANCIENT COASTAL TOWN By William Caraher, R. Scott Moore, and David K. Pettegrew with contributions by Maria Andrioti, P. Nick Kardulias, Dimitri Nakassis, and Brandon R. Olson AMERICAN SCHOOLS OF ORIENTAL RESEARCH • BOSTON, MA Pyla-Koutsopetria I: Archaeological Survey of an Ancient Coastal Town by William Caraher, R. Scott Moore, and David K. Pettegrew Te American Schools of Oriental Research © 2014 ISBN 978-0-89757-069-5 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Caraher, William R. (William Rodney), 1972- Pyla-Koutsopetria I : archaeological survey of an ancient coastal town / by William Caraher, R. Scott Moore, and David K. Pettegrew ; with contributions by Maria Andrioti, P. Nick Kardulias, Dimitri Nakassis, and Brandon Olson. pages cm. -- (Archaeological reports ; volume 21) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-89757-069-5 (alkaline paper) 1. Pyla-Kokkinokremos Site (Cyprus) 2. Archaeological surveying--Cyprus. 3. Excavations (Archaeology)--Cyprus. 4. Bronze age--Cyprus. 5. Cyprus--Antiquities. I. Moore, R. Scott (Robert Scott), 1965- II. Pettegrew, David K. III. Title. DS54.95.P94C37 2014 939’.37--dc23 2014034947 Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper. For Our Parents, Fred and Nancy Caraher Bob and Joyce Moore Hal and Sharon Pettegrew Introduction to A Provisional Linked Digital Version of Pyla-Koutsopetria I: Archaeological Survey of an Ancient Coastal Town We are very pleased to release a digital version of Pyla-Koutsopetria I: Archaeological Survey of an Ancient Coastal Town (2014). -

Study of the Geomorphology of Cyprus

STUDY OF THE GEOMORPHOLOGY OF CYPRUS FINAL REPORT Unger and Kotshy (1865) – Geological Map of Cyprus PART 1/3 Main Report Metakron Consortium January 2010 TABLE OF CONTENTS PART 1/3 1 Introduction 1.1 Present Investigation 1-1 1.2 Previous Investigations 1-1 1.3 Project Approach and Scope of Work 1-15 1.4 Methodology 1-16 2 Physiographic Setting 2.1 Regions and Provinces 2-1 2.2 Ammochostos Region (Am) 2-3 2.3 Karpasia Region (Ka) 2-3 2.4 Keryneia Region (Ky) 2-4 2.5 Mesaoria Region (Me) 2-4 2.6 Troodos Region (Tr) 2-5 2.7 Pafos Region (Pa) 2-5 2.8 Lemesos Region (Le) 2-6 2.9 Larnaca Region (La) 2-6 3 Geological Framework 3.1 Introduction 3-1 3.2 Terranes 3-2 3.3 Stratigraphy 3-2 4 Environmental Setting 4.1 Paleoclimate 4-1 4.2 Hydrology 4-11 4.3 Discharge 4-30 5 Geomorphic Processes and Landforms 5.1 Introduction 5-1 6 Quaternary Geological Map Units 6.1 Introduction 6-1 6.2 Anthropogenic Units 6-4 6.3 Marine Units 6-6 6.4 Eolian Units 6-10 6.5 Fluvial Units 6-11 6.6 Gravitational Units 6-14 6.7 Mixed Units 6-15 6.8 Paludal Units 6-16 6.9 Residual Units 6-18 7. Geochronology 7.1 Outcomes and Results 7-1 7.2 Sidereal Methods 7-3 7.3 Isotopic Methods 7-3 7.4 Radiogenic Methods – Luminescence Geochronology 7-17 7.5 Chemical and Biological Methods 7-88 7.6 Geomorphic Methods 7-88 7.7 Correlational Methods 7-95 8 Quaternary History 8-1 9 Geoarchaeology 9.1 Introduction 9-1 9.2 Survey of Major Archaeological Sites 9-6 9.3 Landscapes of Major Archaeological Sites 9-10 10 Geomorphosites: Recognition and Legal Framework for their Protection 10.1 -

Larnaka Gastronomy Establishments

Catering and Entertainment Establishments for LARNAKA 01/02/2019 Category: RESTAURANT Name Address Telephone Category/ies 313 SMOKE HOUSE 57, GRIGORI AFXENTIOU STREET, AKADEMIA CENTER 99617129 RESTAURANT 6023, LARNACA 36 BAY STREET 56, ATHINON AVENUE, 6026, LARNACA 24621000 & 99669123 RESTAURANT, PUB 4 FRIENDS 5, NIKIFOROU FOKA STREET, 6021, LARNACA 96868616 RESTAURANT A 33 GRILL & MEZE RESTAURANT 33, AIGIPTOU STREET, 6030, LARNACA 70006933 & 99208855 RESTAURANT A. & K. MAVRIS CHICKEN LODGE 58C, ARCH. MAKARIOU C' AVENUE, 6017, LARNACA 24-651933, 99440543 RESTAURANT AKROYIALI BEACH RESTAURANT MAZOTOS BEACH, 7577, MAZOTOS 99634033 RESTAURANT ALASIA RESTAURANT LARNACA 38, PIALE PASIA STREET, 6026, LARNACA 24655868 RESTAURANT ALCHEMIES 106-108, ERMOU STREET, STOA KIZI, 6022, LARNACA 24636111, 99518080 RESTAURANT ALEXANDER PIZZERIA ( LARNAKA ) 101, ATHINON AVENUE, 6022, LARNACA 24-655544, 99372013 RESTAURANT ALFA CAFE RESTAURANT ΛΕΩΦ. ΓΙΑΝΝΟΥ ΚΡΑΝΙΔΙΩΤΗ ΑΡ. 20-22, 6049, ΛΑΡΝΑΚΑ 24021200 RESTAURANT ALMAR SEAFOOD BAR RESTAURANT MAKENZY AREA, 6028, LARNACA RESTAURANT, MUSIC AND DANCE AMENTI RESTAURANT 101, ATHINON STREET, 6022, LARNACA 24626712 & 99457311 RESTAURANT AMIKOS RESTAURANT 46, ANASTASI MANOLI STREET, 7520, XYLOFAGOU 24725147 & 99953029 RESTAURANT ANAMNISIS RECEPTION HALL 52, MICHAEL GEORGIOU STREET, 7600, ATHIENOU 24-522533 RESTAURANT ( 1 ) Catering and Entertainment Establishments for LARNAKA 01/02/2019 Category: RESTAURANT Name Address Telephone Category/ies ANNA - MARIA RESTAURANT 30, ANTONAKI MANOLI STREET, 7730, AGIOS THEODOROS 24-322541 RESTAURANT APPETITO 33, ARCH. MAKARIOU C' AVENUE, 6017, LARNACA 24818444 RESTAURANT ART CAFE 1900 RESTAURANT 6, STASINOU STREET, 6023, LARNACA 24-653027 RESTAURANT AVALON 6-8, ZINONOS D. PIERIDI STREET, 6023, LARNACA 99571331 RESTAURANT B. & B. RESTAURANT LARNACA-DEKELIA ROAD, 7041, OROKLINI 99-688690 & 99640680 RESTAURANT B.B. BLOOMS BAR & GRILL 7, ATHINON AVENUE, 6026, LARNACA 24651823 & 99324827 RESTAURANT BALTI HOUSE TANDOORI INDIAN REST. -

Cyprus Authentic Route 2

Cyprus Authentic Route 2 Safety Driving in Cyprus Comfort Rural Accommodation Tips Useful Information Only DIGITAL Version A Village Life Larnaka • Livadia • Kellia • Troulloi • Avdellero • Athienou • Petrofani • Lympia • Ancient Idalion • Alampra • Mosfiloti • Kornos • Pyrga • Stavrovouni • Kofinou • Psematismenos • Maroni • Agios Theodoros • Alaminos • Mazotos • Kiti • Hala Sultan Tekke • Larnaka Route 2 Larnaka – Livadia – Kellia – Troulloi – Avdellero – Athienou – Petrofani – Lympia - Ancient Idalion – Alampra – Mosfiloti – Kornos – Pyrga – Stavrovouni – Kofinou – Psematismenos – Maroni – Agios Theodoros – Alaminos – Mazotos – Kiti – Hala Sultan Tekke – Larnaka Margo Agios Arsos Pyrogi Spyridon Agios Tremetousia Tseri Golgoi Sozomenos Melouseia Athienou Potamia Pergamos Petrofani Troulloi Margi Nisou Dali Pera Louroukina Avdellero Pyla Chorio Idalion Kotsiatis Lympia Alampra Agia Voroklini Varvara Agios Kellia Antonios Kochi Mathiatis Sia Aradippou Mosfiloti Agia Livadia Psevdas Anna Ε4 Kalo Chorio Port Kition Kornos Chapelle Delikipos Pyrga Royal LARNAKA Marina Salt LARNAKA BAY Lake Hala Sultan Stavrovouni Klavdia Tekkesi Dromolaxia- Dipotamos Meneou Larnaka Dam Kiti Dam International Alethriko Airport Tersefanou Anglisides Panagia Kivisili Menogeia Kiti Aggeloktisti Perivolia Aplanta Softades Skarinou Kofinou Anafotida Choirokoitia Alaminos Mazotos Cape Kiti Choirokoitia Agios Theodoros Tochni Psematismenos Maroni scale 1:300,000 0 1 2 4 6 8 10 Kilometers Zygi AMMOCHOSTOS Prepared by Lands and Surveys Department, Ministry of Interior, -

0005 0006 0007 0011 0014 0017 0018 0019 0021 0022 0025 0026

Up dated 30/1/2018 APPROVED DAIRY PROCESSING PLANTS Serial Approval No. No. Name of Establishment Address Region Capacity ** Phone No. Fax.No. 1 0005 MIMI ELENI Apostolou Louca 33, 7731 Skarinou, Larnaca Larnaca C 24 32 20 14 24 32 20 21 FARM ATHANASIS OLYMBIOU & 2 Philopappou 11 A, 4002 Mesa Gitonia, Limassol Limassol C 99 68 17 80 25 72 72 00 0006 SONS LTD 24 32 22 56 3 MARIA PROXENOU Pentadaktylou 44A, 7735 Kofinou, Larnaca Larnaca C 24 32 29 96 0007 99 66 52 84 Akadimias 2, III Industrial Area Limassol, Ypsonas, 4193 4 DETELINA DAIRY LTD Limassol C 25 71 54 50 25 71 02 14 0011 Limassol 5 0014 YIANNAKIS & ZOIRO STEFANI LTD 1st April 8, 4700 Pachna, Limassol Limassol C 99 60 48 82 25 94 22 40 6 0017 PITTAS DAIRIES LTD 207 Limassol Avenue, 2235 Latsia, Nicosia Nicosia A 22 48 12 50 22 48 59 04 GALAKTOKOMIO STELIOS. S. 25 57 37 48 7 Zia Giocalp 8, 3010 Limassol Limassol C 25 39 35 48 0018 STAVRINOU (LYGIA) 25 39 35 48 Georgiou Kalogeropoulou, 4007 Mesa Gitonia, Limassol GALAKTOKOMIKA PROIONTA M. 25 33 27 41 8 ( Postal Address: Pantelitsas Panayiotou 3, 3080 Limassol C 25 73 83 14 0019 LOIZOU LTD 99 49 2034 Limassol) 9 0021 ZITA DAIRIES LTD P.O. Box 60176, 8101 Paphos Paphos B 26 95 36 96 26 81 80 00 Aradippou Industrial Area B - Emporiou No. 24 - 25 - PETROU BROS DAIRY PRODUCTS 10 Larnaca (Postal Address P.O. Box 40260, 6302 Larnaca A 24 66 12 10 24 66 25 57 0022 LTD Larnaca) ANTROULLA & EFTICHIOS 24 36 00 18 11 Ammochostos Avenue, 7643 Kalo Chorio, Larnaca Larnaca C 24 63 72 02 0025 TRIFILLIS 99 43 28 08 12 0026 NIKI MICHAEL Demokratias 1, 4601 Prastio Avdemou, Limassol Limassol C 25 22 15 60 25 22 17 63 FARMA A.P. -

Implementation of Sewerage Systems in Cyprus

MINISTRY OF AGRICULTURE , NATURAL RESOURCES AND ENVIRONMENT Monitoring of the Implementation Plan in Cyprus Current Status Dr. Dinos A. Poullis Executive Engineer Water Development Department Ministry of Agriculture Natural Resources and Environment Contents Accession Treaty Commitments National Implementation Plan Stakeholders in the Implementation Plan Sewerage Boards Organizational Setup Information and Data Sources for the Preparation of the Implementaton Plan Implementation – current status Work to be Done Difficulties in Implementation Concluding Remarks Accession Treaty Commitments Transitional period negotiated in the accession treaty of Cyprus for the implementation of the UWWTD, Articles 3, 4 and 5(2) ◦ 31.12.2012 Three interim deadlines concerning four agglomerations>15.000pe ◦ 31.12.2008 – 2 agglomerations (Limassol and Paralimni) ◦ 31.12.2009 - 1 agglomeration (Nicosia) ◦ 31.12.2011 - 1 agglomeration (Paphos) National Implementation Plan National Implementation Plan2005 ◦ Submitted to the EC in March 2005 ◦ 6 Urban agglomerations – 545.000pe ◦ 36 Rural agglomerations – 130.000pe National Implementation Plan2008 ◦ Working Groups for Reporting and the EC Guidance Document ◦ Revised NIP-2008 (agglomeration methodology, new technical solutions, government policies and law amendments) ◦ 7 Urban agglomerations – 630.000pe ◦ 50 Rural agglomerations – 230.000pe Article 17 ◦ A revised Implementation Plan is under preparation. Stakeholders in the Implementation Plan Council of Ministers (overall responsibility for the Implementation Plan) Ministry of Agriculture, Natural Resources and Environment Ministry of Interior Ministry of Finance Planning Bureau Sewerage Boards (Established and operate under the “Sewerage Systems Laws 1971 to 2004”) ◦ Urban Sewerage Boards ◦ Rural Sewerage Boards Sewerage Boards Organizational Setup Urban Sewerage Boards ◦ Autonomous organizations (technically and administratively competent) ◦ Carry out their own design, tendering, construction and operation of their sewerage systems. -

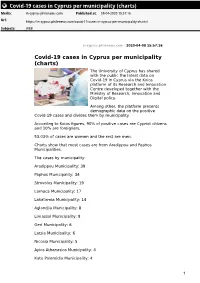

Covid-19 Cases in Cyprus Per Municipality (Charts) Media: In-Cyprus.Philenews.Com Published At: 08-04-2020 15:57:16

Covid-19 cases in Cyprus per municipality (charts) Media: in-cyprus.philenews.com Published at: 08-04-2020 15:57:16 Url: https://in-cyprus.philenews.com/covid-19-cases-in-cyprus-per-municipality-charts/ Subjects: WEB in-cyprus.philenews.com - 2020-04-08 15:57:16 Covid-19 cases in Cyprus per municipality (charts) The University of Cyprus has shared with the public the latest data on Covid-19 in Cyprus via the Koios platform of its Research and Innovation Centre developed together with the Ministry of Research, Innovation and Digital policy. Among other, the platform presents demographic data on the positive Covid-19 cases and divides them by municipality. According to Koios figures, 90% of positive cases are Cypriot citizens and 10% are foreigners. 53.03% of cases are women and the rest are men. Charts show that most cases are from Aradippou and Paphos Municipalities. The cases by municipality: Aradippou Municipality: 39 Paphos Municipality: 34 Strovolos Municipality: 19 Larnaca Municipality: 17 Lakatamia Municipality: 14 Aglandjia Municipality: 8 Limassol Municipality: 8 Geri Municipality: 6 Latsia Municipality: 6 Nicosia Municipality: 5 Ayios Athanasios Municipality: 4 Kato Polemidia Municipality: 4 1 Covid-19 cases in Cyprus per municipality (charts) Media: in-cyprus.philenews.com Published at: 08-04-2020 15:57:16 Url: https://in-cyprus.philenews.com/covid-19-cases-in-cyprus-per-municipality-charts/ Subjects: WEB Mesa Geitonia Municipality: 4 Paralimni Municipality: 4 Mammari: 4 Meniko: 4 Ypsonas Municipality: 4 Yeroskipou Municipality: -

SEWERAGE SYSTEMS in CYPRUS National Implementation Programme Directive 91/271/EEC for the Treatment of Urban Waste Water

SEWERAGE SYSTEMS IN CYPRUS National Implementation Programme Directive 91/271/EEC for the treatment of Urban Waste Water Pantelis Eliades SiSenior EtiExecutive EiEngineer Head of the Wastewater and Re‐use Division Water Development Department «Water Treatment –Sewage» Spanish – Cypriot Partnering Event Hilton Hotel, Nicosia, 15 March 2010 Contents • Introduction • Requirements of the Directive 91/271/EEC • Implementation Programme of Cyprus(IP‐2008) – Description – CliCompliance DtDates – Current Situation – RidRequired IttInvestments / Financ ing • Collection Networks • Waste Water Treatment Plants • Re‐use of Treated Waste Water 2 Introduction • The Council Directive 91/271/EEC concerns the collection, treatment and discharge of urban wastewater with objective the protection of the environment. • According to Artilicle 17 of the Diiirective, Cyprus establish ed an Implementation Programme which concerns: – 57 Agglomerations – Population Equivalent(p.e.) 860.000 – Investments €1.430 million – Co‐Financ ing by EU €125 million • The Ministry of Agriculture, Natural Resources and Environment has the overall responsibility for the implementation of the Directive 3 Requirements of the Directive 91/271/EEC • Installation of collec tion netktworksand wastttewater tttreatmen t plants for secondary or equivalent treatment, in the agglomerations with population equivalent (p.e.) greater than 2000, (Articles 3 and 4) • More stringent treatment in sensitive areas which are subject to eutrophication – removal of Nitrogen and Phosphorus (Article 5) -

UNFICYP 2930 R100 Oct19 120%

450000 E 500000 E 550000 E 600000 E 650000 32o 30' 33o 00' 33o 30' 34o 00' 34o 30' Cape Andreas 395000 N HQ UNFICYP 395000 N MEDITERRANEAN SEA HQ UNPOL 联塞部队部署 Rizokarpaso FMPU Multinational UNFICYP DEPLOYMENT Ayia Trias DÉPLOIEMENT DE L’UNFICYP MFR UNITED KINGDOM Yialousa o o Vathylakas 35 30' 35 30' ДИСЛОКАЦИЯ ВСООНК ARGENTINA Leonarisso HQ Sector 2 DESPLIEGUE DE L A UNFICYP Ephtakomi ARGENTINA UNITED KINGDOM Galatia Cape Kormakiti SLOVAKIA Akanthou Komi Kebir UNPOL 500 m HQ Sector 1 Ardhana Karavas KYRENIA 500 m Kormakiti Lapithos Ayios Amvrosios Temblos Boghaz ARGENTINA / PARAGUAY / BRAZIL Dhiorios Myrtou 500 m Bellapais Trypimeni Trikomo ARGENTINA / CHILE 500 m 500 m Famagusta SECTOR 1 Lefkoniko Bay Sector 4 UNPOL VE WE K. Dhikomo Chatos WE XE HQ 390000 N UNPOL Kythrea 390000 N UNPOL VD WD ari WD XD Skylloura m Geunyeli Bey Keuy K. Monastir SLOVAKIA Mansoura Morphou am SLOVAKIA K. Pyrgos Morphou Philia Dhenia M Kaimakli Angastina Strovilia Post Kokkina Bay P. Zodhia LP 0 Prastio 90 Northing 9 Northing Selemant Limnitis Avlona UNPOL Pomos NICOSIA UNPOL 500 m Karavostasi Xeros UNPA Tymbou (Ercan) FAMAGUSTA UNPOL s s Cape Arnauti ti it a Akaki SECTOR 2 o Lefka r Kondea Kalopsidha Varosha Yialia Ambelikou n e o Arsos m m r a Khrysokhou a ro te rg Dherinia s t s Athienou SECTOR 4 e Bay is s ri SLOVAKIA t Linou A e P ( ) Mavroli rio P Athna Akhna 500 m u Marki Prodhromi Polis ko Evrykhou 500 m Klirou Troulli 1000 m S Louroujina UNPOL o o Pyla 35 00' 35 00' Kakopetria 500 mKochati Lymbia 1000 m DHEKELIA Ayia Napa Cape 500 m Pedhoulas SLOVAKIA S.B.A. -

The Click Beetles of Cyprus with Descriptions of Two New Species and Notes on Species of the Genus Haterumelater Ohira, 1968 (Coleoptera: Elateridae)

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Zeitschrift der Arbeitsgemeinschaft Österreichischer Entomologen Jahr/Year: 2003 Band/Volume: 55 Autor(en)/Author(s): Preiss Rüdiger, Platia Giuseppe Artikel/Article: The Click Beetles of Cyprus with descriptions of two new species and notes on species of the genus Haterumelater Ohira, 1968 (Coleoptera: Elateridae). 97-123 ©Arbeitsgemeinschaft Österreichischer Entomologen, Wien, download unter www.biologiezentrum.at Z.Arb.Gem.Öst.Ent. 55 97-123 1 Wien, 15. 12.2003 ISSN 0375-5223 The Click Beetles of Cyprus with descriptions of two new species and notes on species of the genus Haterumelater OHIRA, 1968 (Coleoptera: Elateridae) Rüdiger PREISS and Giuseppe PLATIA Abstract During a 3-year stay in Cyprus (Preiss) new material was collected and access to the collections of the Ministry of Agriculture in Nicosia, of Mr. Makris and Mr. Georgiou in Limassol and of the Agricultural University in Athens led to a revision of the elaterid fauna of Cyprus. The present contribution treats 37 species. Nine species are recorded for the first time from Cyprus. Two new species are described. Drasterius makrisi n. sp. can be separated from the very variable D. bimaculatus (ROSSI, 1790) by the coarse puncturation on the disc of the wider pronotum. Cardiophorus georgioui n. sp. can easily be distinguished from Cardiophorus miniaticollis CANDÈZE, 1860 by the orange coloured legs and from some south European species (Italy), in particular C. argiolus (GÉNÉ, 1836) and C. ulcerosus (GÉNÉ, 1836), by the absence of markings on the pronotum. The female of Agriotes magnami PLATIA & GUDENZI, 1996 is also described. -

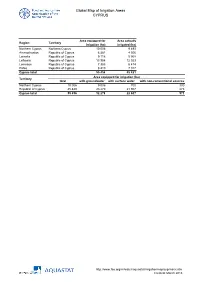

Global Map of Irrigation Areas CYPRUS

Global Map of Irrigation Areas CYPRUS Area equipped for Area actually Region Territory irrigation (ha) irrigated (ha) Northern Cyprus Northern Cyprus 10 006 9 493 Ammochostos Republic of Cyprus 6 581 4 506 Larnaka Republic of Cyprus 9 118 5 908 Lefkosia Republic of Cyprus 13 958 12 023 Lemesos Republic of Cyprus 7 383 6 474 Pafos Republic of Cyprus 8 410 7 017 Cyprus total 55 456 45 421 Area equipped for irrigation (ha) Territory total with groundwater with surface water with non-conventional sources Northern Cyprus 10 006 9 006 700 300 Republic of Cyprus 45 449 23 270 21 907 273 Cyprus total 55 456 32 276 22 607 573 http://www.fao.org/nr/water/aquastat/irrigationmap/cyp/index.stm Created: March 2013 Global Map of Irrigation Areas CYPRUS Area equipped for District / Municipality Region Territory irrigation (ha) Bogaz Girne Main Region Northern Cyprus 82.4 Camlibel Girne Main Region Northern Cyprus 302.3 Girne East Girne Main Region Northern Cyprus 161.1 Girne West Region Girne Main Region Northern Cyprus 457.9 Degirmenlik Lefkosa Main Region Northern Cyprus 133.9 Ercan Lefkosa Main Region Northern Cyprus 98.9 Guzelyurt Lefkosa Main Region Northern Cyprus 6 119.4 Lefke Lefkosa Main Region Northern Cyprus 600.9 Lefkosa Lefkosa Main Region Northern Cyprus 30.1 Akdogan Magosa Main Region Northern Cyprus 307.7 Gecitkale Magosa Main Region Northern Cyprus 71.5 Gonendere Magosa Main Region Northern Cyprus 45.4 Magosa A Magosa Main Region Northern Cyprus 436.0 Magosa B Magosa Main Region Northern Cyprus 52.9 Mehmetcik Magosa Main Region Northern -

First Mtdna Sequences and Body Measurements for Rattus Norvegicus from the Mediterranean Island of Cyprus

life Article First mtDNA Sequences and Body Measurements for Rattus norvegicus from the Mediterranean Island of Cyprus Eleftherios Hadjisterkotis 1, George Konstantinou 2, Daria Sanna 3,*, Monica Pirastru 3 and Paolo Mereu 3 1 Agricultural Research Institute, P.O. Box 22016, Nicosia 1516, Cyprus; [email protected] 2 Society for the Protection of Natural Heritage and the Biodiversity of Cyprus, Keryneias 6, Geri 2200, Cyprus; [email protected] 3 Department of Biomedical Sciences, University of Sassari, Viale San Pietro 43/b, 07100 Sassari, Italy; [email protected] (M.P.); [email protected] (P.M.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 12 June 2020; Accepted: 3 August 2020; Published: 5 August 2020 Abstract: Invasive species are the primary driver of island taxa extinctions and, among them, those belonging to the genus Rattus are considered as the most damaging. The presence of black rat (Rattus rattus) on Cyprus has long been established, while that of brown rat (Rattus norvegicus) is dubious. This study is the first to provide molecular and morphological data to document the occurrence of R. norvegicus in the island of Cyprus. A total of 223 black rats and 14 brown rats were collected. Each sample was first taxonomically attributed on the basis of body measurements and cranial observations. Four of the specimens identified as R. norvegicus and one identified as R. rattus were subjected to molecular characterization in order to corroborate species identification. The analyses of the mitochondrial control region were consistent with morphological data, supporting the taxonomic identification of the samples. At least two maternal molecular lineages for R.