The Relationship of Personal Morality to Lawyering and Professional Ethics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

4 Main Ideas and Supporting Details in Writing

4 Main Ideas and Supporting Details in Writing A paragraph is a series of sentences that support a main idea, or point. A paragraph typically starts with the main idea or point (also called the topic sentence), and the rest of the paragraph provides specific details to support and develop the point. The illustration below shows the relationship between point and support. Support Support Support Support Outlining An outline is a helpful way to plan a paper or to analyze it. An outline shows at a glance the point of a paper and a numbered list of the items that support the point. Here is an example of a paragraph and an outline of the paragraph. 1People in my family love our dog Punch. 2However, I have several reasons for wanting to get rid of Punch. 3First of all, he knows I don’t like him. 4Sometimes he gives me an evil look and curls his top lip back to show me his teeth. 5The message is clearly, “Someday I’m going to bite you.” 6Another reason to get rid of Punch is he sheds everywhere. 7Every surface in our house is covered with Punch hair. 8I spend more time brushing it off my clothes than I do mowing the lawn. 9Last of all, Punch is an early riser, while (on weekends) I am not. 10He will start barking and whining to go outside at 7 a.m., and it’s my job to take care of him. 11When I told my family that I had a list of good reasons for getting rid of Punch, they said they would make up a list of reasons to get rid of me. -

Private. Lives

JJLJ-L, I ..}u.... t I 4.rl @ THE UNIVERSITY THEATRE 1950·51 Season Films and Plays THE September 6-8: Opm City, Italian .film 21, 22: j ean Cocteau's B.eauty and the Beast, French film UNIVERSITY 28,29: The Dam11ed, French film OF October ~. 6: Antoine and AntoitJette, French film 12, 13: BJ(ape from Yesterday, French film HAWAII 19,20: The Raven, French film 26,27: The Barber of Seville, French Opera Comique film THEATRE November 7, 11: Theatre Group production of Lawrence and Armina Langner's THE PURSUIT OF HAPPINESS GROUP 14-18: THE PURSUIT OF HAPPINESS 24-25: Pagnol's Marius, French film December 1, 2: Pagnol's Cnar, French film 7·9: Cage of Nightingales, French film 30: Theatre Group production of Bernard Shaw's MAJOR BARBARA January 5, 6: MAJOR BARBARA 10-13: MAJOR BARBARA February 8, 9: Jouvet in Between Eleven and Midnight, French film 15, 16: Gigi, French film \ 22,23: Kreutzer Sonata, French film March 15-17: Theatre Group.production of THE HOUSE OF SUGAWARA, a newly NOEL COWARD'S translated Kabuki play 20-24: THE HOUSE OF SUGAWARA 27·29: THE HOUSE OF SUGAW ARA 30, 31: Light of India, Indian film PRIVATE. LIVES April 6: T!Je Ghost Goes Wm, American fil~ 13: Museum of Modern Art film, the Marx Brothers in Dudz Soup 14: Shoeshine, Italian film 21-22: Theatre Group production of William Wycherly's THE COUNTRY WIFE 25-28: THE COUNTRY WIFE May 2, 3, 5: The Soul of ChinR, Chinese film 4: Museum of Modem Art film, Garbo in Annt~ Chrhtie 11·12: Theatre Group production of FOUR ORIGINAL PRIZE PLAYS 17·19: FOUR ORIGINAL PRIZE PLAYS June 1: Museum of Modem Art film, Chaplin's Essanay Comedies 8,9: Theatre Group production of Noel Coward's PRIVATE LIVES 14-16: PRIVATE LIVES JUNE 8, 9, 14. -

Private Lives and Public Leadership

DiscernmentSo that you may be able to discern what is best. Phil. 1:10 Private Lives and Public Leadership ■ For many Americans, the impeachment trial Can a homemaker live a life secreted away from Inside: of William Jefferson Clinton is merely another the family, behind a closed door, without it bear- opportunity to express disgust with government ing fruit in the more public parts of one’s house? Where Should We and an invasive news media. In the following pages, our authors sharp- Draw the Line? 2 Although ample justification exists to en our capacity to judge more justly and com- regret the impeachment process, I am disap- passionately.As we stretch our moral faculty, A Case for pointed in one of the most frequently stated may our eyes be opened to see God’s eternal Telling More 4 reasons—the wish that Congress would put the wisdom come to bear on the intractable moral president’s personal matters aside and “get on decisions of everyday life. God Cannot with the business of the coun- I am pleased to introduce Be Privatized 6 try.” I respond,Why should we our new editor, Mr. Stan separate a president’s moral Guthrie. He has big shoes to Panelists Explore choices from the business of the “Why should we fill, taking over for our col- Theme During country? Aren’t questions of league, Mark Fackler. Mark Roundtable 8 truth-telling, personal integrity, separate a ended his superb run as editor and legal process central to the president’s moral this past summer with his move The Link Between citizen-formation process? from Wheaton to Calvin Private Lives We must recognize the choices from the College. -

Private Lives, Public House—The White-Ellery House

PRIVATE LIVES, PUBLIC HOUSE: THE STORY OF THE FAMILIES WHO LIVED IN THE WHITE-ELLERY HOUSE LECTURE FINDING AID & TRANSCRIPT Speakers: Stephanie Buck and Martha Oaks Date: 4/3/2010 Runtime: 1:00:58 Camera Operator: Bob Quinn Identification: VL21; Video Lecture #21 Citation: Buck, Stephanie, and Martha Oaks. “Private Lives, Public House: The Story of the Families Who Lived in the White-Ellery House.” CAM Video Lecture Series, 4/3/2010. VL21, Cape Ann Museum Library & Archives, Gloucester, MA. Copyright: Requests for permission to publish material from this collection should be addressed to the Librarian/Archivist. Language: English Finding Aid: Description: Karla Kaneb, 4/20/2020. Transcript: Monica Lawton, 5/6/2020. Video Description This lecture is the first of many events planned by the Cape Ann Museum in 2010 to celebrate the 300th anniversary of the White-Ellery House. In this presentation, archivist and librarian Stephanie Buck recounts the life of the Reverend John White (1677-1760) for whom the house was built in 1710. As the pastor of the Private Lives, Public House – The White-Ellery House: The Stories of the Families Who Lived There – VL00 – page 2 First Parish Church in Gloucester, White lived in the house until 1733. Curator Martha Oaks picks up next when ownership is transferred to the Ellery family in 1740, several generations of which remained at the house until it was given to the museum in 1947. From early colonial times to the building of Route 128, this deep dive into the archival collections of the museum highlights the changes that have been experienced by the people of Gloucester as personified in this remarkably well-preserved historic structure. -

Resource Pack.Indd

Noël Coward’s Private Lives Lesson Resource Pack Director Lucy Bailey Designer Katrina Lindsay Lighting Designer Oliver Fenwick Music Errollyn Wallen Image: Noël Coward photographed by Horst P Horst in 1933. Horst Estate/Courtesy Staley-Wise Gallery, New York Contents Introduction & Cast List ……………………… 3 Information for Teachers................................ 4 Noël Coward by Sheriden Morley…………… 5 In Conversation with Lucy Bailey................... 7 Private Lives by John Knowles....…..……. 9 Synopsis …………..…………………………… 11 Social Class................................................... 12 Noël Coward: In his own words….…….…….. 13 Noël Coward visits Hampstead Theatre......... 14 Texts for Comparison with Private Lives…… 15 Performance Evaluation…..………..….....….. 16 Set Design by Katrina Lindsay....................... 17 Language of Private Lives.............................. 18 Lesson Activities - Worksheet one………………………………… 20 Worksheet two………………………………… 21 Worksheet three………………………………. 22 Worksheet four………………………………… 23 Worksheet fi ve…………………………………. 24 Script Extract……….………………………….. 25 Further reading………………………………… 29 Introduction Amanda and Elyot can’t live together and they can’t live apart. When they discover they are honey- mooning in the same hotel with their new spouses, they not only fall in love all over again, they learn to hate each other all over again. A comedy with a dark underside, fi reworks fl y as each character yearns desperately for love. Full of wit and razor sharp dialogue, Private Lives remains one of the most successful and popular comedies ever written. Written in 1929, Private Lives was brilliantly revived at Hampstead in 1962, bringing about a ‘renaissance’ in Coward’s career and establishing Hampstead as a prominent new theatre for London. Private Lives was a runaway hit when it debuted in 1930, and the play has remained popular in revivals ever since. -

Public and Private Lives: Women in St. Petersburg at the Turn of the Century

Tampa Bay History Volume 8 Issue 1 Article 3 6-1-1986 Public and Private Lives: Women in St. Petersburg at the Turn of the Century Ellen Babb Milly St. Julien Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/tampabayhistory Recommended Citation Babb, Ellen and Julien, Milly St. (1986) "Public and Private Lives: Women in St. Petersburg at the Turn of the Century," Tampa Bay History: Vol. 8 : Iss. 1 , Article 3. Available at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/tampabayhistory/vol8/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Open Access Journals at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Tampa Bay History by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Babb and Julien: Public and Private Lives: Women in St. Petersburg at the Turn of PUBLIC AND PRIVATE LIVES: WOMEN IN ST. PETERSBURG AT THE TURN OF THE CENTURY by Ellen Babb and Milly St. Julien An American woman living at the turn of the century was frequently depicted as a portrait of a middle-class housewife and mother, frozen at the doorstep of her home. Her place was the familial domicile where she posed as the loving, supportive companion to her more worldly husband and as the nurturing, educating mother responsible for the proper upbringing of her offspring. The “lady of leisure” rarely worked outside the home, but devoted herself to domestic duties, including the imparting of essential values of discipline, hard work, and sobriety to her children. This training was necessary for the successful integration of these future citizens into the free enterprise system.1 The inference that these women, isolated within their private domains, were passive participants in the economic process who sat on the sidelines of community affairs, veils us from a more accurate and three dimensional view of these women of the late Victorian age. -

CAN't BUY ME LOVE: Funding Marriage Promotion Versus Lis-Tening to Real Needs in Breaking the Cycle of Poverty

CAN’T BUY ME LOVE: FUNDING MARRIAGE PROMOTION VERSUS LISTENING TO REAL NEEDS IN BREAKING THE CYCLE OF POVERTY * ALY PARKER I. INTRODUCTION A. “WE DON’T HAVE MUCH, BUT WE HAVE LOVE.” Anthony watched the worker hastily usher his girlfriend Pam into the small, blue room. The blinds on the door clicked shut behind her, unlike the other rooms in the Civic Center Department of Public Social Services office. The Civic Center Office caters almost exclusively to public assis- tance applicants living in Skid Row, Los Angeles, California. Most of the other rooms don’t even have doors. On a busy day, everybody hears frus- trated applicants arguing with their case workers. Anthony didn’t get up when Pam walked away. He leaned over and apologetically explained to me that he didn’t like leaving her alone, but he wasn’t allowed in the room while she underwent a medical examination. Checking to make sure the blinds were still closed, he opened his tattered manila folder and leafed through his old documents: proof of work applica- tions, letters confirming his medical condition, and handwritten telephone numbers of various community mental health centers. At 60 years old, An- thony’s hands were shaking when he found what he was looking for: a piece of light green paper folded in half with “Anthony” written on the * J.D. Candidate, Class of 2009, University of Southern California, Gould School of Law. Spe- cial thanks to Professor Ron Garet for his guidance and thoughtfulness throughout the process of writ- ing this Note. His dedication to social justice has inspired generations of USC Law students. -

BOYD-QUINSON MAINSTAGE JULY 12-28, 2018 WHERE Norway

JULIANNE BOYD, ARTISTIC DIRECTOR AND Drs. Judith and Martin Bloomfield PRESENT BY Lucas Hnath FEATURING Ashley Bufkin Christopher Innvar Laila Robins Mary Stout SCENIC DESIGNER COSTUME DESIGNER LIGHTING DESIGNER Brian Prather Jen Caprio Chris Lee SOUND DESIGNER WIG DESIGNER Lindsay Jones J. Jared Janas PRODUCTION STAGE MANAGER CASTING Leslie Sears Pat McCorkle, Katja Zarolinski, CSA DIGITAL ADVERTISING BERKSHIRE PRESS REPRESENTATIVE NATIONAL PRESS REPRESENTATIVE The Pekoe Group Charlie Siedenburg Matt Ross Public Relations DIRECTED BY Joe Calarco SPONSORED IN PART BY Anne and Larry Frisman & Susan and David Lombard A Doll's House, Part 2 is presented by special arrangement with Dramatists Play Service, Inc., New York. Originally produced on Broadway by Scott Rudin, Eli Bush, Joey Parnes, Sue Wagner, and John Johnson. Commissioned and first produced by South Coast Repertory. BOYD-QUINSON MAINSTAGE JULY 12-28, 2018 WHERE Norway. Inside the Helmer house. WHEN 15 years since Nora left Torvald. CAST IN ORDER OF APPEARANCE Anne Marie...............................................................................................Mary Stout* Nora ......................................................................................................Laila Robins* Torvald ........................................................................................ Christopher Innvar* Emmy ................................................................................................. Ashley Bufkin* STAFF Production Stage Manager ......................................................................Leslie -

Private Lives

presents Private Lives By: Noel Coward Our student performances are funded by a generous grant from: and The Coates Charitable Foundation 1 The Classic Theatre of San Antonio Study Guide- Private Lives by Noel Coward TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE 3 SYNOPSIS 4 ABOUT THE PLAYWRIGHT 5 HISTORY OF THE PLAY 6 PRODUCTION TEAM 7 THEMES of Private Lives 8 VOCABULARY TERMS 9 “On the Bus”/SURVEY 10 DELVING DEEPER 11 CLASSROOM ACTIVITIES The Classic Theatre mission is to build a professional theatre that inspires passionate involvement in a shared theatrical experience and to create a source of pride for our community. AIM High intern Renelle Wilson (far right) onstage with the cast of Classic Theatre of San Antonio’s award- winning production of Scapin by Moliere. 2 The Classic Theatre of San Antonio Study Guide- Private Lives by Noel Coward SYNOPSIS “I think very few people are completely normal really, deep down in their private lives.”-Amanda Act 1 Following a brief courtship, Elyot and Sibyl are honeymooning at a hotel in Deauville, although her curiosity about his first marriage is not helping his romantic mood. In the adjoining suite, Amanda and Victor are starting their new life together, although he cannot stop thinking of the cruelty Amanda's ex-husband displayed towards her. Elyot and Amanda, following a volatile three-year-long marriage, have been divorced for the past five years, but they now discover that they are sharing a terrace while on their honeymoons with their new and younger spouses. Elyot and Amanda separately beg their new mates to leave the hotel with them immediately, but both new spouses refuse to cooperate and each storms off to dine alone. -

Tom Clancy Book List

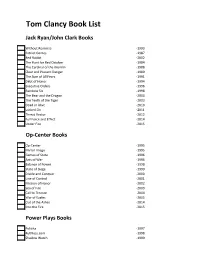

Tom Clancy Book List Jack Ryan/John Clark Books Without Remorse -1993 Patriot Games -1987 Red Rabbit -2002 The Hunt for Red October -1984 The Cardinal of the Kremlin -1988 Clear and Present Danger -1989 The Sum of All Fears -1991 Debt of Honor -1994 Executive Orders -1996 Rainbow Six -1998 The Bear and the Dragon -2000 The Teeth of the Tiger -2003 Dead or Alive -2010 Locked On -2011 Threat Vector -2012 Full Force and Effect -2014 Under Fire -2015 Op-Center Books Op-Center -1995 Mirror Image -1995 Games of State -1996 Acts of War -1996 Balance of Power -1998 State of Siege -1999 Divide and Conquer -2000 Line of Control -2001 Mission of Honor -2002 Sea of Fire -2003 Call to Treason -2004 War of Eagles -2005 Out of the Ashes -2014 Into the Fire -2015 Power Plays Books Politika -1997 Ruthless.com -1998 Shadow Watch -1999 Bio-Strike -2000 Cold War -2001 Cutting Edge -2002 Zero Hour -2003 Wild Card -2004 Net Force Books Net Force -1999 Hidden Agendas -1999 Night Moves -1999 Breaking Point -2000 Point of Impact -2001 CyberNation -2001 State of War -2003 Changing of the Guard -2003 Springboard -2005 The Archimedes Effect -2006 Net Force Explorers Books Virtual Vandals -1998 The Deadliest Game -1998 One is the Loneliest Number -1999 The Ultimate Escape -1999 The Great Race -1999 End Game -1998 Cyberspy -1999 Shadow of Honor -2000 Private Lives -2000 Safe House -2000 Gameprey -2000 Duel Identity -2000 Deathworld -2000 High Wire -2001 Cold Case -2001 Runaways -2001 Splinter Cell Books Splinter Cell -2004 Operation Barracuda -2005 Checkmate -2006 Fallout -2007 Conviction -2009 Endgame -2009 Blacklist Aftermath -2013 Ghost Recon Books Ghost Recon -2008 Combat Ops -2011 EndWar Books EndWar -2008 The Hunted -2011 H.A.W.X. -

2020-21 LTC6 Xmascarol Program.Indd

special holiday event CCharlesharles DDickens’ickens’ A CHRISTMAS CAROL AN ORIGINAL ADAPTATION BY Anthony Lawton INNCO COLLABORATIONCOLLAB ORATION WWITHITH Christopher Colucci ANDAND Thom Weaver STREAMING DECEMBER 4 – 27, 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS 2 Welcome ..........................................................3 From the Dramaturg............................... 4-6 Dickens’ One-Man Christmas Carol .... 4 Christmas Traditions .................................5 “Are there no workhouses?” ...................5 From the Artistic Director .........................7 From the Creators ...................................8-9 Who’s Who .............................................. 10-13 About the Lantern ......................................14 Thank You to Our Donors ..................15-27 Annual Fund ...............................................15 Ticket Donations ...................................... 22 COVER, THIS PAGE, and THROUGHOUT: Anthony Lawton in Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol. All Lantern production photos by Mark Garvin. ©2020 LANTERN THEATER COMPANY / WWW.LANTERNTHEATER.ORG WELCOME 3 LANTERN THEATER COMPANY Charles McMahon Stacy Maria Dutton ARTISTIC DIRECTOR EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR in partnership with MIRROR THEATRE COMPANY presents Charles Dickens’ A CHRISTMAS CAROL AN ORIGINAL ADAPTATION BY Anthony Lawton IN COLLABORATION WITH Christopher Colucci & Thom Weaver Thom Weaver Kierceton Keller SCENIC & LIGHTING DESIGNER COSTUME DESIGNER Christopher Colucci Lydia Stahl SOUND DESIGNER STAGE MANAGER © 2020. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. FURTHER -

Pigs, Party Secretaries, and Private Lives in Hungary Author(S): Martha Lampland Source: American Ethnologist, Vol

Pigs, Party Secretaries, and Private Lives in Hungary Author(s): Martha Lampland Source: American Ethnologist, Vol. 18, No. 3, Representations of Europe: Transforming State, Society, and Identity (Aug., 1991), pp. 459-479 Published by: Wiley on behalf of the American Anthropological Association Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/645589 Accessed: 29-06-2019 20:32 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms American Anthropological Association, Wiley are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to American Ethnologist This content downloaded from 137.110.34.112 on Sat, 29 Jun 2019 20:32:18 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms pigs, party secretaries, and private lives in Hungary MARTHA LAMPLAND-University of California, San Diego It did not take long to learn that in the village the Communist party secretary was universally disliked. Initially, only veiled comments were tendered in my presence; with time, however, more open criticisms were leveled, criticisms of his style, his demeanor, his history in office. But perhaps the most scathing criticism of all was that he was a do-nothing (dologtalan). When I first heard this criticism voiced, my friend impressed upon me that not only was the party secretary himself a do-nothing, but his entire family had always been so.