The SABPP Women's Report 2013

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Economic Development Department on Annual Report 2012/13

ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT DEPARTMENT Annual Report 2012 - 2013 CONTENTS ECONOMY HIGHLIGHTS ......................................................................................................... 2 EDD AND AGENCY HIGHLIGHTS.............................................................................................. 3 1. PART A: GENERAL INFORMATION ............................................................................... 4 1.1 Overview of the Report and Policy and Commitment Statement by Minister Ebrahim Patel ............................................................................................. 5 1.2 Statement by Deputy Minister Professor Hlengiwe Mkhize ....................................... 20 1.3 Overview of the Accounting Officer ........................................................................... 22 1.4 Entities reporting to the Minister .............................................................................. 24 1.5 Strategic Overview ................................................................................................... 25 1.6 Legislative and Other Mandates ............................................................................... 26 1.7 Organisational Structure .......................................................................................... 28 1.8 Contact Details ......................................................................................................... 29 1.9 List of Abbreviations ................................................................................................ -

Covid-19 Regulatory Update 01Jun2020

Covid-19 Regulatory Update: 01 June 2020 CONTENTS CONFIRMED CASES .................................................. 2 LOCKDOWN REGULATIONS ..................................... 6 CULTURAL AFFAIRS .................................................. 2 SOCIAL SECURITY ..................................................... 6 EDUCATION ................................................................ 2 SPORT ......................................................................... 7 EMPLOYMENT LAW ................................................... 3 TOBACCO ................................................................... 7 ENERGY & MINING ..................................................... 4 TOURISM ..................................................................... 7 FINANCIAL LAW / RELIEF FUNDS............................. 5 TRADE AND INDUSTRY ............................................. 8 HEALTH AND SAFETY ............................................... 5 TRANSPORTATION .................................................... 8 Index to Covid-19 regulations and notices: https://juta.co.za/covid-19-legislation-update/2020/05/21/index/ Lexinfo Practice Management Alert This newsletter is published bi-monthly and focuses on issues such as client care, innovation, legal technology, management, leadership, remote working, work-life balance, knowledge management, libraries, succession, management, skills development, artificial intelligence, human resources, libraries, marketing and branding. The latest edition, March to April 2020, is now -

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report: Volume 2

VOLUME TWO Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report The report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission was presented to President Nelson Mandela on 29 October 1998. Archbishop Desmond Tutu Ms Hlengiwe Mkhize Chairperson Dr Alex Boraine Mr Dumisa Ntsebeza Vice-Chairperson Ms Mary Burton Dr Wendy Orr Revd Bongani Finca Adv Denzil Potgieter Ms Sisi Khampepe Dr Fazel Randera Mr Richard Lyster Ms Yasmin Sooka Mr Wynand Malan* Ms Glenda Wildschut Dr Khoza Mgojo * Subject to minority position. See volume 5. Chief Executive Officer: Dr Biki Minyuku I CONTENTS Chapter 1 Chapter 6 National Overview .......................................... 1 Special Investigation The Death of President Samora Machel ................................................ 488 Chapter 2 The State outside Special Investigation South Africa (1960-1990).......................... 42 Helderberg Crash ........................................... 497 Special Investigation Chemical and Biological Warfare........ 504 Chapter 3 The State inside South Africa (1960-1990).......................... 165 Special Investigation Appendix: State Security Forces: Directory Secret State Funding................................... 518 of Organisations and Structures........................ 313 Special Investigation Exhumations....................................................... 537 Chapter 4 The Liberation Movements from 1960 to 1990 ..................................................... 325 Special Investigation Appendix: Organisational structures and The Mandela United -

LIST of MEMBERS (Female)

As on 28 May 2021 LIST OF MEMBERS (Female) 6th Parliament CABINET OFFICE-BEARERS OF THE NATIONAL ASSEMBLY MEMBERS OF THE NATIONAL ASSEMBLY As on 28 May 2021 MEMBERS OF THE EXECUTIVE (alphabetical list) Minister of Agriculture, Land Reform and Rural Development ............. Ms A T Didiza Minister of Basic Education ....................................................... Mrs M A Motshekga Minister of Communications and Digital Technologies ....................... Ms S T Ndabeni-Abrahams Minister of Cooperative Governance and Traditional Affairs ............... Dr N C Dlamini-Zuma Minister of Defence and Military Veterans ..................................... Ms N N Mapisa-Nqakula Minister of Forestry, Fisheries and Environment ............................... Ms B D Creecy Minister of Human Settlements, Water and Sanitation ...................... Ms L N Sisulu Minister of International Relations and Cooperation ......................... Dr G N M Pandor Minister of Public Works and Infrastructure ................................... Ms P De Lille Minister of Small Business Development ....................................... Ms K P S Ntshavheni Minister of Social Development .................................................. Ms L D Zulu Minister of State Security ......................................................... Ms A Dlodlo Minister of Tourism ................................................................. Ms M T Kubayi-Ngubane Minister in The Presidency for Women, Youth and Persons with Disabilities ..................................................................... -

Report of the 54Th National Conference Report of the 54Th National Conference

REPORT OF THE 54TH NATIONAL CONFERENCE REPORT OF THE 54TH NATIONAL CONFERENCE CONTENTS 1. Introduction by the Secretary General 1 2. Credentials Report 2 3. National Executive Committee 9 a. Officials b. NEC 4. Declaration of the 54th National Conference 11 5. Resolutions a. Organisational Renewal 13 b. Communications and the Battle of Ideas 23 c. Economic Transformation 30 d. Education, Health and Science & Technology 35 e. Legislature and Governance 42 f. International Relations 53 g. Social Transformation 63 h. Peace and Stability 70 i. Finance and Fundraising 77 6. Closing Address by the President 80 REPORT OF THE 54TH NATIONAL CONFERENCE 1 INTRODUCTION BY THE SECRETARY GENERAL COMRADE ACE MAGASHULE The 54th National Conference was convened under improves economic growth and meaningfully addresses the theme of “Remember Tambo: Towards inequality and unemployment. Unity, Renewal and Radical Socio-economic Transformation” and presented cadres of Conference reaffirmed the ANC’s commitment to our movement with a concrete opportunity for nation-building and directed all ANC structures to introspection, self-criticism and renewal. develop specific programmmes to build non-racialism and non-sexism. It further directed that every ANC The ANC can unequivocally and proudly say that we cadre must become activists in their communities and emerged from this conference invigorated and renewed drive programmes against the abuse of drugs and to continue serving the people of South Africa. alcohol, gender based violence and other social ills. Fundamentally, Conference directed every ANC We took fundamental resolutions aimed at radically member to work tirelessly for the renewal of our transforming the lives of the people for the better and organisation and to build unity across all structures. -

Zuma's Cabinet Reshuffles

Zuma's cabinet reshuffles... The Star - 14 Feb 2018 Switch View: Text | Image | PDF Zuma's cabinet reshuffles... Musical chairs reach a climax with midnight shakeup LOYISO SIDIMBA [email protected] HIS FIRST CABINET OCTOBER 2010 Communications minister Siphiwe Nyanda replaced by Roy Padayachie. His deputy would be Obed Bapela. Public works minister Geoff Doidge replaced by Gwen MahlanguNkabinde. Women, children and people with disabilities minister Noluthando MayendeSibiya replaced by Lulu Xingwana. Labour minister Membathisi Mdladlana replaced by Mildred Oliphant. Water and environmental affairs minister Buyelwa Sonjica replaced by Edna Molewa. Public service and administration minister Richard Baloyi replaced by Ayanda Dlodlo. Public enterprises minister Barbara Hogan replaced by Malusi Gigaba. His deputy became Ben Martins. Sport and recreation minister Makhenkesi Stofile replaced by Fikile Mbalula. Arts and culture minister Lulu Xingwana replaced by Paul Mashatile. Social development minister Edna Molewa replaced by Bathabile Dlamini. OCTOBER 2011 Public works minister Gwen MahlanguNkabinde and her cooperative governance and traditional affairs counterpart Sicelo Shiceka are axed while national police commissioner Bheki Cele is suspended. JUNE 2012 Sbu Ndebele and Jeremy Cronin are moved from their portfolios as minister and deputy minister of transport respectively Deputy higher education and training minister Hlengiwe Mkhize becomes deputy economic development minister, replacing Enoch Godongwana. Defence minister Lindiwe Sisulu moves to the Public Service and Administration Department, replacing the late Roy Padayachie, while Nosiviwe MapisaNqakula moves to defence. Sindisiwe Chikunga appointed deputy transport minister, with Mduduzi Manana becoming deputy higher education and training minister. JULY 2013 Communications minister Dina Pule is fired and replaced with former cooperative government and traditional affairs deputy minister Yunus Carrim. -

Pocket Guide to South Africa 2010/2011: Government

GOVERNMENT 19 Pocket Guide to South Africa 2010/11 GOVERNMENT Government’s outcomes approach is embedded in and a direct resultant of the electoral mandate. Five priority areas were identified: decent work and sus- tainable livelihoods, education, health, rural development, food security and land reform and the fight against crime and corruption. These translated into 12 outcomes to create a better life for all: • an improved quality of basic education • a long and healthy life for all South Africans • all South Africans should be safe and feel safe • decent employment through inclusive growth • a skilled and capable workforce to support an inclusive growth path • an efficient, competitive and responsive economic infra- structure network • vibrant, equitable, sustainable rural communities with food security for all • sustainable human settlements and an improved quality of household life • a responsive, accountable, effective and efficient local government system • environmental assets and natural resources that are well protected and enhanced • a better Africa and a better world as a result of South Africa’s contributions to global relations • an efficient and development-oriented public service and an empowered, fair and inclusive citizenship. In 2010, performance agreements for the outcomes were signed between President Jacob Zuma and Cabinet ministers. Delivery agreements will further unpack each outcome. The Department for Performance Monitoring and Evaluation in The Presidency will facilitate the process of regular reporting and monitoring of progress against the agreed outputs and targets in the delivery agreements. This process will foster an understanding of how the various spheres of government are working together to achieve the outcomes. The Presidency, March 2011 President: Jacob Zuma Deputy President: Kgalema Motlanthe 20 The Constitution The Constitution is the supreme law of the country. -

35911 30-11 Legala Layout 1

Government Gazette Staatskoerant REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA REPUBLIEK VAN SUID-AFRIKA Vol. 569 Pretoria, 30 November 2012 No. 35911 LEGAL NOTICES A WETLIKE KENNISGEWINGS N.B. The Government Printing Works will not be held responsible for the quality of “Hard Copies” or “Electronic Files” submitted for publication purposes AIDS HELPLINE: 0800-0123-22 Prevention is the cure 201541—A 35911—1 2 No. 35911 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 30 NOVEMBER 2012 IMPORTANT NOTICE The Government Printing Works will not be held responsible for faxed documents not received due to errors on the fax machine or faxes received which are unclear or incomplete. Please be advised that an “OK” slip, received from a fax machine, will not be accepted as proof that documents were received by the GPW for printing. If documents are faxed to the GPW it will be the sender’s respon- sibility to phone and confirm that the documents were received in good order. Furthermore the Government Printing Works will also not be held responsible for cancellations and amendments which have not been done on original documents received from clients. TABLE OF CONTENTS LEGAL NOTICES Page BUSINESS NOTICES.............................................................................................................................................. 11 Gauteng..................................................................................................................................................... 11 Eastern Cape............................................................................................................................................ -

Party List Rank Name Surname African Christian Democratic Party

Party List Rank Name Surname African Christian Democratic Party National 1 Kenneth Raselabe Joseph Meshoe African Christian Democratic Party National 2 Steven Nicholas Swart African Christian Democratic Party National 3 Wayne Maxim Thring African Christian Democratic Party Regional: Western Cape 1 Marie Elizabeth Sukers African Independent Congress National 1 Mandlenkosi Phillip Galo African Independent Congress National 2 Lulama Maxwell Ntshayisa African National Congress National 1 Matamela Cyril Ramaphosa African National Congress National 2 David Dabede Mabuza African National Congress National 3 Samson Gwede Mantashe African National Congress National 4 Nkosazana Clarice Dlamini-Zuma African National Congress National 5 Ronald Ozzy Lamola African National Congress National 6 Fikile April Mbalula African National Congress National 7 Lindiwe Nonceba Sisulu African National Congress National 8 Zwelini Lawrence Mkhize African National Congress National 9 Bhekokwakhe Hamilton Cele African National Congress National 10 Nomvula Paula Mokonyane African National Congress National 11 Grace Naledi Mandisa Pandor African National Congress National 12 Angela Thokozile Didiza African National Congress National 13 Edward Senzo Mchunu African National Congress National 14 Bathabile Olive Dlamini African National Congress National 15 Bonginkosi Emmanuel Nzimande African National Congress National 16 Emmanuel Nkosinathi Mthethwa African National Congress National 17 Matsie Angelina Motshekga African National Congress National 18 Lindiwe Daphne Zulu -

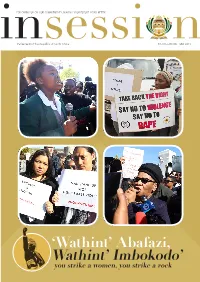

Wathint' Imbokodo'

FOLLOWING UP ON OUR COMMITMENTS, MAKING YOUR FUTURE WORK BETTER Parliament of the Republic of South Africa SPECIAL EDITION • GBV 2019 ‘Wathint’ Abafazi, Wathint’ Imbokodo’ you strike a women, you strike a rock Vision An activist and responsive people’s Parliament that improves the quality of life of South Africans and ensures enduring equality in our society. Mission Parliament aims to provide a service to the people of South Africa by providing the following: • A vibrant people’s Assembly that intervenes and transforms society and addresses the development challenges of our people; • Effective oversight over the Executive by strengthening its scrutiny of actions against the needs of South Africans; Provinces of Council National of • Participation of South Africans in the decision-making of National Assembly National of processes that affect their lives; • A healthy relationship between the three arms of the State, Black Rod Mace Mace that promotes efficient co-operative governance between the spheres of government, and ensures appropriate links with our region and the world; and • An innovative, transformative, effective and efficient parliamentary service and administration that enables Members of Parliament to fulfil their constitutional responsibilities. Strategic Objectives 1. Strengthening oversight and accountability 2. Enhancing public involvement 3. Deepening engagement in international fora 4. Strengthening co-operative government 5. Strengthening legislative capacity 6 8 10 12 14 Contents 5. Presiding Officers condemn brutality -

1 Minister Maite Nkoana-Mashabane Deputy Minister Nomaindia Mfeketo

Minister Maite Nkoana-Mashabane Deputy Minister Nomaindia Mfeketo Deputy Minister Lluwellyn Landers [email protected], Vol. 5 2014 1 Minister Maite Nkoana-Mashabane receiving the President of Kenya, Uhuru Kenyatta, for the Presidential Inauguration at the Air Force Base Waterkloof, Pretoria IN THIS ISSUE contents 4 Letter from the Editor 5 Did you know? FEATURE 6 Presidential Inauguration 2014 8 South Africa’s new Cabinet 8 South Africa: an integrated, active member of the international community NATIONAL DAY CELEBRATIONS 15 Gabarone 16 Hong Kong 17 Kampala 18 Windhoek 19 Bucharest 19 Algiers 20 Manila 21 Seoul 22 São Paulo 23 Tokyo 24 Brasilia 25 Luanda 26 Tunis 27 Athens 32 28 Conakry 29 South Africans voting in Bangkok REBOOT 30 Word puzzle 6 8 6 30 Soduko 31 Learn a new language PRESIDENTIAL INAUGURATION 32 Photo collage 2 [email protected], Vol. 5 2014 [email protected], Vol. 5 2014 3 the it’s your voice South Africa participated in the Western The Department of Arts and the diplomat is an internal newsletter Sahara International Film Festival, Culture recently conducted a sod- of the Department of International Relations which took place from 29 April to 4 May turning ceremony to launch the and Cooperation published by the 1 2 2014 in the Sahrawi refugee camps construction of the Sarah Baartman Branch: Public Diplomacy in South Western Algeria. It included Centre of Memory. Situated at her EDITOR-IN-CHIEF a special tribute to Nelson Mandela burial site, the centre will honour Clayson Monyela as well as film screenings, workshops and document the life of Baartman MANAGING EDITOR and a performance by South African and the heritage of the Khoisan Michelle Greeff musician Jonas Mosa Gwangwa. -

Statement on the Virtual Cabinet Meeting of Wednesday, 5 August 2020 | the Presidency

Statement on the virtual Cabinet Meeting of Wednesday, 5 August 2020 |... http://www.thepresidency.gov.za/cabinet-statements/statement-virtual-ca... I I THE PRESIDENCY REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA- (-/)· MAIN MENU PresidencyZA/?ref=mf) https://www.youtube.co Presidential Hotline: 17737 (http://www.dpme.gov.za Search the Presidency /keyfocusareas/hotlineSite/Pages/default.aspx) Statement on the virtual Cabinet Meeting of Wednesday, 5 August Commission in The Presidency 2020 independent commission A. Focus on Corruption for the remuneration of public office-bearers 1. Abuse of resources for Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) interventions REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA 1.1. Cabinet reflected with disappointment on recent reports of acts of corruption and theft From the Desk of the President of the much-needed resources that government has allocated to save lives and livelihoods during the COVID-19 pandemic. 1.2. Some unscrupulous individuals and companies have been looting state resources that were meant to provide food to needy families and personal protective equipment (PPEs) to frontline officials, particularly healthcare workers. (/from-the-desk-of-the-president/desk- 1.3. Such criminal and immoral activities included inflating quoted prices, intercepting and president%2C-monday%2C-03- redirecting food parcels meant for the poor, and acts of fraud involving funds designated to alleviate the hardships of employees and businesses affected by the shutting down of august-2020) economic activities during the national lockdown. Issue: 03 August 2020 Chairship of the African Union 1.4. Cabinet has called on all public institutions to uphold the highest standards of integrity and accountability, and fulfil their mandates effectively and efficiently.