Commodification and the Figure of the Castrato in Smollettâ•Žs Humphry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wiley John Williams, BM

1-- q ASPECTS OF IDIOMATIC HARMONY IN THE HARPSICHORD SONATAS OF DOMENICO SCARLATTI THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State College in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF MUSIC By Wiley John Williams, B. M. Denton, Texas June, 1961 TABLE O CONTENTS Page Lr3 ISTRTIOS. .. .. .. .. iy Chapter I. BI10GRAPHY. a . II. THE STYLE OF THE SONATAS . 8 III. HA2MOSIC 3TYE -. - . 12 Modality Leading Tone Functions of Lower Neighbor Tones Modulation Cyclic Modulation Unprepared Modulation General Types of Dissonance Polychordal Progressions Dissonance Occurring in Modulation Extended 'ertal Harmony Permutating Contrapuntal Combinations IV. CONCLUSIONI.. .a. .a. ... ,. 39 ,IBLI RAP HY . .a .. a . .. 0.0. .0 .0 .. 0 .0 .0 .. .. 41 iii LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Figure Page 1. Longo 180--iv-V Phrygian Cadence . 14 2. Longo 202--Parallel Fifths Between iv and V . - - -. 15 Chords -. " - - - - - - - - 3. Longo 273--Modulating Figure Based on Phrygian Cadence. - . 15 4. Longo 257--Resembles Pure Phrygian Mode. 16 5. Longo 260--Phrygian Cadence and Dominant Pedal 17 6. Longo 257--Major and Minor Scale in Contrary Motion . " . 17 7. Long 309--Leading Tone Effect on I, IV, V . 18 8. Longo 309--Leading Tone Effect on I and II . 19 9. Long 342--Non-harmonic Tones are Turning Points of Scale Motion . 20 10. Longo 273--Raised Fourth Degree Delays Upper Voice Progress . 21 11. Longo 281--Alterations Introduce Modulation. 22 12. Longo 178--Raised Fourth Scale Degree. 22 13. Longo 62--Upper Harmonic Minor Tetrachords . 23 14. Longo 124--Raised Lower Neighbor Tones and Principal Tones Produce Melody. -

Note by Martin Pearlman the Castrato Voice One of The

Note by Martin Pearlman © Martin Pearlman, 2020 The castrato voice One of the great gaps in our knowledge of "original instruments" is in our lack of experience with the castrato voice, a voice type that was at one time enormously popular in opera and religious music but that completely disappeared over a century ago. The first European accounts of the castrato voice, the high male soprano or contralto, come from the mid-sixteenth century, when it was heard in the Sistine Chapel and other church choirs where, due to the biblical injunction, "let women remain silent in church" (I Corinthians), only men were allowed to sing. But castrati quickly moved beyond the church. Already by the beginning of the seventeenth century, they were frequently assigned male and female roles in the earliest operas, most famously perhaps in Monteverdi's L'Orfeo and L'incoronazione di Poppea. By the end of that century, castrati had become popular stars of opera, taking the kinds of leading heroic roles that were later assigned to the modern tenor voice. Impresarios like Handel were able to keep their companies afloat with the star power of names like Farinelli, Senesino and Guadagni, despite their extremely high fees, and composers such as Mozart and Gluck (in the original version of Orfeo) wrote for them. The most successful castrati were highly esteemed throughout most of Europe, even though the practice of castrating young boys was officially forbidden. The eighteenth-century historian Charles Burney described being sent from one Italian city to another to find places where the operations were performed, but everyone claimed that it was done somewhere else: "The operation most certainly is against law in all these places, as well as against nature; and all the Italians are so much ashamed of it, that in every province they transfer it to some other." By the end of the eighteenth century, the popularity of the castrato voice was on the decline throughout Europe because of moral and humanitarian objections, as well as changes in musical tastes. -

THE CASTRATO SACRIFICE: WAS IT JUSTIFIED? Jennifer Sowle, B.A

THE CASTRATO SACRIFICE: WAS IT JUSTIFIED? Jennifer Sowle, B.A. Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 2006 APPROVED: Elizabeth King Dubberly, Major Professor Stephen Dubberly, Committee Member Jeffrey Snider, Committee Member Graham Phipps, Director of Graduate Studies in the College of Music James C. Scott, Dean of the College of Music Sandra L. Terrell, Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Sowle, Jennifer, The Castrato Sacrifice: Was it Justified? Master of Arts (Music), August 2006, 65 pages, references, 30 titles. One of the greatest mysteries in the history of music is the castrato singers of the Baroque era. Castration has existed for many thousands of years, but for the first time in history, it was used for artistic purposes. Who were these men who seemingly gave up their masculinity for the sake of music? By examining the time period and circumstances in which these musicians lived, an answer may be found. Exploring the economic, social, and political structure of the 17th and 18th centuries may reveal the mindset behind such a strange yet accepted practice. The in-depth study of their lives and careers will help lift the veil of mystery that surrounds them. Was their physical sacrifice a blessing or a curse? Was it worth it? Copyright 2006 by Jennifer Sowle ii Perhaps the greatest mystery in the history of opera is the Italian castrato singers of the Baroque period. These strange phenomena can more easily be seen as ethereal voices whose mystique cannot be duplicated by any amount of modern training or specialized technique, rather than as human musicians who simply wanted to perform or serve the Church with their unique talent. -

Cross Gender Roles in Opera

Boys Will Be Girls, Girls Will Be Boys: Cross Gender Roles in Opera University at Buffalo Music Library Exhibit October 1, 2003-January 9, 2004 An exhibit focusing on the high-voiced male castrato singers and on “pants roles,” in which women sing male roles. Created in conjunction with “Gender Week @ UB” 2003. Curated by Nara Newcomer CASE 1: Castrati : Introduction The opera stage is one place where gender roles have always been blurred, disguised, even switched – possibly multiple times within the course of an opera! Italian composers of seventeenth and eighteenth century opera seria (“serious opera” – as distinguished from comic opera) were especially free in this regard, largely connected with the high-voiced male castrati. Such traditions are not solely confined to that era, however. This exhibit will examine gender roles in opera, focusing on the castrati and upon operatic travesty, specifically upon breeches parts (“pants roles”). The photographs in the section of the exhibit on breeches parts come from the Music Library’s J. Warren Perry Collection of Memorabilia which includes over 2,000 photographs, largely operatic. Many of the photographs bear the singer’s autographs and are inscribed to Dr. Perry. A castrato is a type of high-voiced male singer, produced by castrating young boys with promising voices before they reached puberty. Castrati rose to prominence in the Italian opera seria of the 17th and 18th centuries. They were the prima donnas, even the rock stars, of their day. Somewhat ironically, however, the era of castrati both began and ended in the church. Castrati are known to have existed in Western Europe by the 1550’s and were present for centuries before in the Byzantine church. -

Farinelli Or Concerning the Vocal Derivations of the Old Custom of Castration Oscar Bottasso

Original JMM Farinelli or Concerning the Vocal Derivations of the Old Custom of Castration Oscar Bottasso Instituto de Inmunología. Facultad de Ciencias Médicas, Universidad Nacional de Rosario (Argentina). Correspondence: Oscar Bottasso. Facultad de Ciencias Médicas. Santa Fe 3100. Rosario -2000- (Argentina). e-mail: [email protected] Received 14 October 2009; accepted 2 January 2010 Summary The film presents some of the passages of the life of Carlo Broschi, the famous Farinelli, a castrato who delighted so many lovers of the settecentista opera. Upon witnessing a street challenge between the young singer and a young trumpeter, over which Farinelli is victorious due to his extraordinary voice, George F. Handel, at the time an official musician of the English court and being present almost by chance, proposes a trip to London. Farinelli rejects the offer which leads to a tense relation between the two of them, a relationship full of antipathies but at the same time with a certain degree of mutual recog- nition. In contrast to Farinelli’s scarcely addressed confinement in the Spanish court, at the peak of his career, the film is rich in showing us the varied visits of the Broschi brothers to different European sce- narios, blended with episodes where Farinelli’s seductive character triggers numerous love scenes final- ly consummated by his brother Ricardo, anatomically intact. According to the physiopathology of prepu- bertal castration this seems more over-acted than real. Keywords: Carlo Broschi, Castration, Farinelli, Gérard Corbiau, Haendel. Technical details (Benedict), Omero Antonutti (Nicola Porpora), Marianne Basler (Countess Mauer) Pier Paolo Title: Farinelli. Capponi (Broschi) Graham Valentine (Prince of Original title: Farinelli. -

Castrati Singers and the Lost "'Cords"9 Meyer M

744 CASTRATI SINGERS AND THE LOST "'CORDS"9 MEYER M. MELICOW, M.D. * Given Professor Emeritus of Uropathology Research Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons New York, New York In the Italian language, nouns of feminine gender end with "a", while those of masculine gender end with "o"-yet we label Joan Sutherland a soprano, not soprano and Marian Anderson a contralto, not contralto. Why? T HE year 1600, with the performance of Euridice composed by Jacopo Peri, marks the birth of modem opera. 1-4 Prior to that date, Greek- style dramas were performed in which polyphonic choruses dominated. Vincenzo Galilei, the father of Galileo, and Jacopo Peri rebelled against this and introduced a significant innovation by employing single vocal parts consisting of arias and recitatives. This in time led to bel canto, often for sheer vocal display. At first there were no public opera houses, and performances were given in private theaters or chapels belonging to kings, dukes, bishops, etc. But opera soon caught on and in 1637 the first public opera houses opened in Venice. By 1700 Venice had 17 opera houses and there were hundreds throughout Italy. Some were very ornate, displaying a mixture of baroque and rococo styles. Soon there were performances in Germany (sangspiel), France (opera bouffe, later opera comique), Poland, Sweden, and England (where it was labeled "ballad opera"). 1,2,3 Composers and producers of opera had a problem because for centuries women were not allowed to sing in church or theater. There were no women singers; all roles, male and female, were played by men. -

Farinelli CD Featuring Ann Hallenberg out Now with Exclusive Anniversary Sampler to Mark Les Talens Lyriques’ 25Th Anniversary

Farinelli CD featuring Ann Hallenberg out now with exclusive anniversary sampler to mark Les Talens Lyriques’ 25th anniversary Ann Hallenberg Les Talens Lyriques Christophe Rousset Aparté AP117 OUT NOW Following their sell-out Farinelli concerts, Christophe Rousset and the Swedish mezzo-soprano Ann Hallenburg release their much-anticipated recording: Farinelli – A Portrait, out now on Aparté. The recording, made from a live radio broadcast in Norway, includes works by composers Broschi, J.C Bach, Giacomelli, Porpora, Hasse and Leo that were sung by the world’s most famous 18th century castrato. The success of the soundtrack to the film Farinelli (1994), which sold more than a million discs worldwide, firmly established Les Talens Lyriques on the international Baroque scene two decades ago. To mark the ensemble’s 25th anniversary, an exclusive sampler of 25 tracks accompanies the Farinelli disc, with music from Les Talens Lyriques’ rich collection of recordings. The Farinelli disc coincides with the release of the Handelian diptych Alcina/Tamerlano by Les Talens Lyriques and Rousset with Outhere. Rousset and Hallenberg have formed a fierce partnership over the past years through their Farinelli collaboration, presenting these long-forgotten gems of the Italian operatic repertoire across Europe to critical acclaim and packed concert halls. Today only few singers can master the pyrotechnics, vocal range and breath control that the castrati uniquely possessed in the past. Hallenberg, who was awarded with a 2016 International Opera Award, also features on the Blu-ray of the Handel double bill production by Pierre Audi of Alcina and Tamerlano, performed by Les Talens Lyriques and conducted by Christophe Rousset. -

Il Farinelli a Bologna Mostra Storico-Documentaria

Il Farinelli a Bologna Mostra storico-documentaria in occasione del 300° anniversario della nascita di Carlo Broschi detto il Farinelli 6-30 aprile 2005 Museo internazionale e biblioteca della musica di Bologna Carlo Broschi detto Farinelli (1705-1782), forse il più celebre cantante di tutti i tempi, si esibì varie volte a Bologna tanto da essere insignito della cittadinanza onoraria bolognese nell'ottobre 1732; un mese più tardi acquistò un podere fuori Porta Lame, con il progetto di edificarvi una villa, nella quale trascorrere la vecchiaia una volta ritiratosi dalle scene. Dopo un lungo soggiorno in Spagna, il Farinelli si stabilì definitivamente a Bolo- gna il 19 agosto 1761, rimanendovi fino alla sua morte, avvenuta il 16 settembre 1782. Nella sua magnifica villa in Via Lame 228 (oggi Via Zanardi 30) visse con una piccola corte di artisti, coltivando i rapporti con le più influenti corti europee. Il Farinelli è sepolto alla Certosa di Bologna, purtroppo il suo immenso patrimonio è an- dato disperso e la sua villa demolita del 1949. La mostra Il Farinelli a Bologna riunisce circa 250 riproduzioni di documenti, lettere, immagini e dipin- ti; particolare attenzione è stata riservata alla ricostruzio- ne degli ambienti e dell'atmosfera della villa del Farinel- li, oggi perduta. Allestita nella primavera 2001 a Palazzo Dall'Armi Marescalchi, in occasione della Terza Setti- mana della Cultura promossa dal Ministero per i Beni e le Attività Culturali, nel 2005 è stata ospite ad Andria, città natale del Farinelli, per iniziativa del Comune di Andria e dell’Associazione Misure Composte. La mostra è curata da Luigi Verdi, con la consulenza storica e ico- nografica di Francesca Boris, Maria Pia Jacoboni, Vin- cenzo Lucchese e Carlo Vitali. -

The Eroticism of Emasculation: Confronting the Baroque Body of the Castrato Author(S): Roger Freitas Freitas Source: the Journal of Musicology, Vol

The Eroticism of Emasculation: Confronting the Baroque Body of the Castrato Author(s): Roger Freitas Freitas Source: The Journal of Musicology, Vol. 20, No. 2 (Spring 2003), pp. 196-249 Published by: University of California Press Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/jm.2003.20.2.196 Accessed: 03-10-2018 15:00 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms University of California Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Journal of Musicology This content downloaded from 146.57.3.25 on Wed, 03 Oct 2018 15:00:19 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms The Eroticism of Emasculation: Confronting the Baroque Body of the Castrato ROGER FREITAS A nyone who has taught a survey of baroque music knows the special challenge of explaining the castrato singer. A presentation on the finer points of Monteverdi’s or Handel’s art can rapidly narrow to an explanation of the castrato tradition, a justification 196 for substituting women or countertenors, and a general plea for the dramatic viability of baroque opera. As much as one tries to rationalize the historical practice, a treble Nero or Julius Caesar can still derail ap- preciation of the music drama. -

Music in the Classical Era (Mus 7754)

MUSIC IN THE CLASSICAL ERA (MUS 7754) LOUISIANA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC & DRAMATIC ARTS FALL 2016 instructor Dr. Blake Howe ([email protected]) M&DA 274 meetings Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays, 9:30–10:20 M&DA 221 office hours Fridays, 8:30–9:30, or by appointment prerequisite Students must have passed either the Music History Diagnostic Exam or MUS 3710. Howe / MUS 7754 Syllabus / 2 GENERAL INFORMATION COURSE OBJECTIVES This course pursues the diversity of musical life in the eighteenth century, examining the styles, genres, forms, and performance practices that have retrospectively been labeled “Classical.” We consider the epicenter of this era to be the mid eighteenth century (1720–60), with the early eighteenth century as its most logical antecedent, and the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century as its profound consequent. Our focus is on the interaction of French, Italian, and Viennese musical traditions, but our journey will also include detours to Spain and England. Among the core themes of our history are • the conflict between, and occasional synthesis of, French and Italian styles (or, rather, what those styles came to symbolize) • the increasing independence of instrumental music (symphony, keyboard and accompanied sonata, concerto) and its incorporation of galant and empfindsam styles • the expansion and dramatization of binary forms, eventually resulting in what will later be termed “sonata form” • signs of wit, subjectivity, and the sublime in music of the “First Viennese Modernism” (Haydn, Mozart, early Beethoven). We will seek new critical and analytical readings of well-known composers from this period (Beethoven, Gluck, Haydn, Mozart, Pergolesi, Scarlatti) and introduce ourselves to the music of some lesser-known figures (Alberti, Boccherini, Bologne, Cherubini, Dussek, Galuppi, Gossec, Hasse, Hiller, Hopkinson, Jommelli, Piccinni, Rousseau, Sammartini, Schobert, Soler, Stamitz, Vanhal, and Vinci, plus at least two of J. -

ANN HALLENBERG LES TALENS LYRIQUES CHRISTOPHE ROUSSET Concert Enregistré Le 26 Mai 2011 À Bergen (Grieghallen) Dans Le Cadre Du Festival International De Bergen

ANN HALLENBERG LES TALENS LYRIQUES CHRISTOPHE ROUSSET Concert enregistré le 26 mai 2011 à Bergen (Grieghallen) dans le cadre du Festival international de Bergen. Enregistrement : NRK Mastering : Little Tribeca Traduction française : Jean-François Lattarico (textes chantés 2, 4-6, 8-9, 11), Bénédicte Hertz (textes chantés 1 & 3), Laurent Cantagrel (textes chantés 10-12 & p. 18-28) English translation : Charles Johnston (p. 6-15 and sung texts) Photos © Eric Larrayadieu, © cargocollective.com/vermeesch - Eric Larrayadieu (p.44) Remerciements à Laura et Maurizio Pietrantoni. AP117 © Little Tribeca 2016 p NRK - Les Talens Lyriques 2011 apartemusic.com Farinelli A PORTRAIT - LIVE IN BERGEN ANN HALLENBERG - LES TALENS LYRIQUES - CHRISTOPHE ROUSSET RICCARDO BROSCHI (1698-1756) JOHANN ADOLF HASSE (1699-1783) 1. “Son qual nave ch’agitata” (Arbace) 7’35 7. Ouverture 7’35 extrait/from Artaserse extrait/from Cleofide 2. “Ombra fedele anch ’io” (Dario) 9’42 LEONARDO LEO (1694-1744) extrait/from Idaspe 8. “Che legge spietata” (Arbace) 5’00 GEMINIANO GIACOMELLI (ca. 1692-1740) 9. “Cervo in bosco” (Arbace) 6’13 extrait/from Catone in Utica 3. “Già presso al termine” (Farnaspe) 6’30 extrait/from Adriano in Siria GEORG FRIEDRICH HANDEL (1685-1759) NICOLA PORPORA (1686-1768) 10. “Sta nell’Ircana” (Ruggiero) 5’27 extrait/from Alcina 4. “Si pietoso il tuo labro” (Mirteo) 7’06 11. “Lascia ch’io pianga” (Almirena) 4’41 extrait/from Semiramide riconosciuta extrait/from Rinaldo 5. “Alto Giove” (Acio) 10’19 extrait/from Polifemo NICOLA PORPORA 12. “In braccio a -

Viewed the Thesis/Dissertation in Its Final Electronic Format and Certify That It Is an Accurate Copy of the Document Reviewed and Approved by the Committee

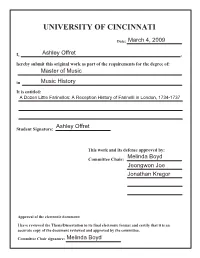

U UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date: March 4, 2009 I, Ashley Offret , hereby submit this original work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Master of Music in Music History It is entitled: A Dozen Little Farinellos: A Reception History of Farinelli in London, 1734-1737 Ashley Offret Student Signature: This work and its defense approved by: Committee Chair: Melinda Boyd Jeongwon Joe Jonathan Kregor Approval of the electronic document: I have reviewed the Thesis/Dissertation in its final electronic format and certify that it is an accurate copy of the document reviewed and approved by the committee. Committee Chair signature: Melinda Boyd A Dozen Little Farinellos: A Reception History of Farinelli in London, 1734-37 A Thesis Submitted to the Division of Graduate Studies and Research of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Music in the Division of Composition, Musicology, and Theory of the College-Conservatory of Music 2009 By Ashley Offret B. M., University of Maine, 2005 Committee Chair: Dr. Melinda Boyd ABSTRACT Farinelli’s arrival in London in 1734 to perform with the Opera of the Nobility marked a temporary rise in the declining popularity of Italian Opera in England. The previous few decades had seen Italian opera overwhelmingly successful under the baton of Georg Frederic Handel, despite frequent and constant complaints by critics. This thesis will reconstruct Farinelli’s reception history through an examination of contemporary literature. First, it will examine Farinelli’s irresistibility as a sexual icon by reconstructing London’s ideas about femininity, while taking into account his unique traits that attracted him to both males and females.