California State Univeristy, Northridge Historic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Historic-Cultural Monument (HCM) List City Declared Monuments

Historic-Cultural Monument (HCM) List City Declared Monuments No. Name Address CHC No. CF No. Adopted Community Plan Area CD Notes 1 Leonis Adobe 23537 Calabasas Road 08/06/1962 Canoga Park - Winnetka - 3 Woodland Hills - West Hills 2 Bolton Hall 10116 Commerce Avenue & 7157 08/06/1962 Sunland - Tujunga - Lake View 7 Valmont Street Terrace - Shadow Hills - East La Tuna Canyon 3 Plaza Church 535 North Main Street and 100-110 08/06/1962 Central City 14 La Iglesia de Nuestra Cesar Chavez Avenue Señora la Reina de Los Angeles (The Church of Our Lady the Queen of Angels) 4 Angel's Flight 4th Street & Hill Street 08/06/1962 Central City 14 Dismantled May 1969; Moved to Hill Street between 3rd Street and 4th Street, February 1996 5 The Salt Box 339 South Bunker Hill Avenue (Now 08/06/1962 Central City 14 Moved from 339 Hope Street) South Bunker Hill Avenue (now Hope Street) to Heritage Square; destroyed by fire 1969 6 Bradbury Building 300-310 South Broadway and 216- 09/21/1962 Central City 14 224 West 3rd Street 7 Romulo Pico Adobe (Rancho 10940 North Sepulveda Boulevard 09/21/1962 Mission Hills - Panorama City - 7 Romulo) North Hills 8 Foy House 1335-1341 1/2 Carroll Avenue 09/21/1962 Silver Lake - Echo Park - 1 Elysian Valley 9 Shadow Ranch House 22633 Vanowen Street 11/02/1962 Canoga Park - Winnetka - 12 Woodland Hills - West Hills 10 Eagle Rock Eagle Rock View Drive, North 11/16/1962 Northeast Los Angeles 14 Figueroa (Terminus), 72-77 Patrician Way, and 7650-7694 Scholl Canyon Road 11 The Rochester (West Temple 1012 West Temple Street 01/04/1963 Westlake 1 Demolished February Apartments) 14, 1979 12 Hollyhock House 4800 Hollywood Boulevard 01/04/1963 Hollywood 13 13 Rocha House 2400 Shenandoah Street 01/28/1963 West Adams - Baldwin Hills - 10 Leimert City of Los Angeles May 5, 2021 Page 1 of 60 Department of City Planning No. -

Historic-Cultural Monument (HCM) List City Declared Monuments

Historic-Cultural Monument (HCM) List City Declared Monuments No. Name Address CHC No.CF No. Adopted Notes 1 Leonis Adobe 23537 Calabasas Road 8/6/1962 2 Bolton Hall 10116 Commerce Avenue 8/6/1962 3 Nuestra Senora la Reina de Los 100-110 Cesar E. Chavez Ave 8/6/1962 Angeles (Plaza Church) & 535 N. Main St 535 N. Main Street & 100-110 Cesar Chavez Av 4 Angel's Flight 4th Street & Hill8/6/1962 Dismantled 05/1969; Relocated to Hill Street Between 3rd St. & 4th St. in 1996 5 The Salt Box (Former Site of) 339 S. Bunker Hill Avenue 8/6/1962 Relocated to (Now Hope Street) Heritage Square in 1969; Destroyed by Fire 10/09/1969 6 Bradbury Building 216-224 W. 3rd Street 9/21/1962 300-310 S. Broadway 7 Romulo Pico Adobe (Rancho Romulo) 10940 Sepulveda Boulevard 9/21/1962 8 Foy House 1335-1341 1/2 Carroll Avenue 9/21/1962 9 Shadow Ranch House 22633 Vanowen Street 11/2/1962 10 Eagle Rock 72-77 Patrician Way 11/16/1962 7650-7694 Scholl Canyon Road Eagle Rock View Drive North Figueroa (Terminus) 11 West Temple Apartments (The 1012 W. Temple Street 1/4/1963 Rochester) 12 Hollyhock House 4800 Hollywood Boulevard 1/4/1963 13 Rocha House 2400 Shenandoah Street 1/28/1963 14 Chatsworth Community Church 22601 Lassen Street 2/15/1963 (Oakwood Memorial Park) 15 Towers of Simon Rodia (Watts 10618-10626 Graham Avenue 3/1/1963 Towers) 1711-1765 E. 107th Street 16 Saint Joseph's Church (site of) 1200-1210 S. -

Glendora Walking Tour

This Walking Tour of Downtown Glendora and Environs is intended to foster awareness of the history and the built landscape of our community. It focuses mainly on the Downtown Business District (DBD) and adjacent A Short Primer on Architectural Styles neighborhoods.What consti- Many architectural styles tend to be associated with particular periods of time. tutes “historical” is somewhat Described below are six styles found in Glendora and referred to in this Guide. subjective but the writers have Note also that the term vernacular is used as well.Vernacular styles tend to be tried to include sites that have “unclassifiable” otherwise so architectural historians will classify structures as somehow played a role in this “vernacular brick” for example to separate them from brick buildings with an community.A later driving tour identifiable standard. Recognizing different styles on the landscape allows us guide to sites outside of the to visualize the areal extent of our community in different eras. Note, for exam- DBD is contemplated. A ple, where bungalows transition into ranch homes east of Finkbiner Park/Cullen Avenue:When was the area to the west built? To the east? What does this tell us about the growth of Glendora? A Victorian Built primarily in the latter 19th century, these wood frame homes have many permutations such as “stick” and “Queen Anne.”They possess a strong verti- cal presence emphasized by tall windows, steep roof pitch, and narrow eaves. Often they are sheathed with various types of shingles, including “fish scales.” B B Craftsman Bungalow A product of the Arts and Crafts Movement of the early 20th century, the Craftsman is epitomized by the work of the Green Brothers in Pasadena (Gamble House).These homes were generally built between 1905 and c. -

The Following Are Just Some of the Projects Our Company Has Worked on to Provide a Compliant Window Cleaning System

THE FOLLOWING ARE JUST SOME OF THE PROJECTS OUR COMPANY HAS WORKED ON TO PROVIDE A COMPLIANT WINDOW CLEANING SYSTEM: 1 Bush Street, San Francisco 1321 Mission Street, San Francisco 1 Sutter Street, San Francisco 1330 Broadway, Oakland 100 California Street, San Francisco 1355 Market Street, San Francisco 100 South Ellsworth Avenue, San Mateo 1380 N. California Boulevard, Walnut Creek 100 Grand Avenue, Oakland 1388 Sutter Street, San Francisco 1000 6th Street, San Francisco 1400 & 1500 Seaport Boulevard, Redwood City 1000 Fourth Street, San Rafael 1400 Mission Street, San Francisco 101 Lombard Street, San Francisco 1430 Q Street, Sacramento 102 Horne Avenue, San Francisco 144 King Street, San Francisco 1035 Folsom Street, San Francisco 145 Guerrero Street, San Francisco 1095 Market Street, San Francisco 1450 Franklin, San Francisco 110 Sutter Street, San Francisco 150 Lombard Street, San Francisco 110 The Embarcadero, San Francisco 150 Post Street, San Francisco 1100 Ocean Avenue, San Francisco 1500 Centre Point Drive, Milpitas 111 Jones Street, San Francisco 1500 San Pablo Avenue, Berkeley 1140 Folsom Street, San Francisco 1500 South Grand, Los Angeles 1150 Sacramento Street, San Francisco 1500 Van Ness Avenue, San Francisco 1155 Battery Street, San Francisco 15046 Broadway Valdez, Oakland 116 New Montgomery Street, San Francisco 15106 Mian Plaza, Camarillo 1178 Folsom Street, San Francisco 1515 South Van Ness Avenue, San Francisco 1200 Ashby Avenue, Berkeley 1528 Central Park South, San Mateo 1207 Indiana Street, San Francisco 153 Townsend Street, San Francisco 1239 Turk Street, San Francisco 1532 Harrison Street, San Francisco 125 Mason Street, San Francisco 1545 Pine Street, San Francisco 1250 Lakeside, Sunnyvale 155 Montgomery Street, San Francisco 1251 Turk Street, San Francisco 155 Sansome Street, San Francisco 1255 Battery Street, San Francisco 1601 Mariposa Street, San Francisco 1296 Shotwell Street, San Francisco 1615 Sutter Street, San Francisco F0 1299 Bush Street, San Francisco 1625 Plymouth Avenue, Mountain View 130 E. -

September/October 2010

Volume 32 sep oct 2010 Number 5 Saving the Sixties: What We’ve Learned by Trudi Sandmeier Pop quiz! The Conservancy’s recent educa- tional initiative, “The Sixties Turn 50,” was: a) eye opening b) thrilling c) like opening Pandora’s box d) all of the above (Answer: d) It’s been ten months since the Conservancy and our Modern Committee launched “The Sixties Turn 50,” celebrating Greater L.A.’s rich legacy of 1960s architecture. We hope you attended some of our many events and spent some time on our website at laconservancy.org/sixties. We also held a photography contest and screened three sixties- related films at this year’s Last Remaining Seats The University Religious Center (Killingsworth, Brady & Associates, 1964) is one of the postwar resources targeted for series. Like a language immersion program, we demolition in USC’s proposed master plan. Photo by LAC staff. focused on “all sixties, all the time.” We had fun and learned a lot. For one thing, Los Angeles has a greater ’60s Modern Resources Targeted for legacy than we had imagined. Sixties buildings are everywhere! We knew the decade was an important Development on USC Campus time in the area’s development, but even we were surprised at what we discovered once we scratched by Flora Chou the surface. While not all of it merits preservation, In May 2010, the University of Southern California (USC) released the draft environmental impact this vast set of resources has come into high relief report (EIR) for a master plan to guide development of new uses on and around the University Park campus and deserves examination. -

ANGELINO HEIGHTS Walking Tour

ANGELINO HEIGHTS Walking Tour Original by Murray Burns of the Angelino Heights Community Organization, 1997 Revised 2006/7 by Marco Antonio García, and LA Conservancy volunteers and staff A note on the revised text: Other than the Los Angeles Times, the major source of information for the biographical information on each homeowner was the Angelino Heights HPOZ Historic Resource Documentation Report; Roger G. Hatheway, Principal Investigator, 1981. Copyright 2007 Los Angeles Conservancy. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced without permission from the Los Angeles Conservancy. History of Los Angeles 3 History of Angelino Heights 4 Historic Preservation Overlay Zone (HPOZ) 8 What is Victorian Architecture? 9 Style – Queen Anne 9 Style – Eastlake 10 EAST EDGEWARE Fire Station #6 11 601 (Lefebvre) 12 600 13 701 (Spanish style Apts) 13 608 (Anna Hall) 14 704 (Henry Hall) 15 710 (Jeanette M. Davies) 16 714 (Hall) 17 720 (Craftsman style duplex) 18 Style: Craftsman 18 724 (Libby) 19 726 (Spanish style Apts) 20 801 (Stilson) 22 CARROLL AVE: South Side 1300 (Phillips) 24 1316 (Russell) 26 1320 (Heim) 27 1324 (Scheerer/Plan Book House) 30 1330 (Sessions) 31 1340 (Thomas) 33 1344 (Haskins) 34 1354 (McManus) 36 1400 Block 37 North Side 1355 (Pinney) 38 1345 (Sanders) 40 1337 (Foy Family) 42 Style-Italianate 44 1329 (Innes) 45 1325 (Irey) 48 1321 49 Style - Stick 50 Appendix I: The Hall Family 51 Appendix II: Social Life in Angelino Heights 52 Appendix III: Glossary 53 Angelino Heights 2007 Page 2 A BRIEF HISTORY OF LOS ANGELES On September 4, 1781, a group of 44 settlers founded El Pueblo De Nuestra Senora Reina De Los Angeles (the Town of the Queen of Angels). -

GC 1323 Historic Sites Surveys Repository

GC 1323 Historic Sites Surveys Repository: Seaver Center for Western History Research, Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County Span Dates: 1974-1996, bulk 1974-1978 Conditions Governing Use: Permission to publish, quote or reproduce must be secured from the repository and the copyright holder Conditions Governing Access: Research is by appointment only Source: Surveys were compiled by Tom Sitton, former Head of History Department, Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County Background: In 1973, the History Department of the Natural History Museum was selected to conduct surveys of Los Angeles County historic sites as part of a statewide project funded through the National Preservation Act of 1966. Tom Sitton was appointed project facilitator in 1974 and worked with various historical societies to complete survey forms. From 1976 to 1977, the museum project operated through a grant awarded by the state Office of Historic Preservation, which allowed the hiring of three graduate students for the completion of 500 surveys, taking site photographs, as well as to help write eighteen nominations for the National Register of Historic Places (three of which were historic districts). The project concluded in 1978. Preferred Citation: Historic Sites Surveys, Seaver Center for Western History Research, Los Angeles County Museum of Natural History Special Formats: Photographs Scope and Content: The Los Angeles County historic site surveys were conducted from 1974 through 1978. Compilation of data for historic sites continued beyond 1978 until approximately 1996, by way of Sitton's efforts to add application sheets prepared for National Register of Historic Places nominations. These application forms provide a breadth of information to supplement the data found on the original survey forms. -

Historic - Cultural Monuments (HCM) Listing City Declared Monuments

Historic - Cultural Monuments (HCM) Listing City Declared Monuments Note: Multiple listings are based on unique names and addresses as supplied by the Departments of Cultural Affairs, Building and Safety and the Department of City Planning Office of Historic Resources (OHR). No. Name Address CPC No. CF No. Adopted Demolished 1 Leonis Adobe 23537 Calabasas Road 8/6/1962 2 Bolton Hall 10116 Commerce Avenue 8/6/1962 3 Nuestra Senora la Reina de Los 535 N. Main Street & 100-110 8/6/1962 Angeles (Plaza Church) Cesar Chavez Av 100-110 Cesar E. Chavez Ave & 535 N. Main St 4 Angel's Flight (Dismantled 5/69) Hill Street & 3rd Street 8/6/1962 5 The Salt Box (Destroyed by Fire) 339 S. Bunker Hill Avenue 8/6/1962 1/1/1969 6 Bradbury Building 300-310 S. Broadway 9/21/1962 216-224 W. 3rd Street 7 Romulo Pico Adobe (Rancho Romulo) 10940 Sepulveda Boulevard 9/21/1962 8 Foy House 1335-1341 1/2 Carroll Avenue 9/21/1962 9 Shadow Ranch House 22633 Vanowen Street 11/2/1962 10 Eagle Rock Eagle Rock View Drive 11/16/1962 North Figueroa (Terminus) 72-77 Patrician Way 7650-7694 Scholl Canyon Road 11 West Temple Apartments (The 1012 W. Temple Street 1/4/1963 2/14/1979 Rochester) 12 Hollyhock House 4800 Hollywood Boulevard 1/4/1963 13 Rocha House 2400 Shenandoah Street 1/28/1963 14 Chatsworth Community Church 22601 Lassen Street 2/15/1963 (Oakwood Memorial Park) 15 Towers of Simon Rodia (Watts 10618-10626 Graham Avenue 3/1/1963 Towers) 1711-1765 E. -

Garden Apartments: Remarkable Collection of Monumental Bridges Spanning the Los Angeles River

Volume 34 J a n f e b 2 0 1 2 number 1 Sixth Street Viaduct to Be Replaced by Cindy Olnick On November 18, 2011, the Los Angeles City Council certified the final environmental impact report for the Sixth Street Viaduct Seismic Retrofit Project. The report calls for the replacement of the 1932 bridge with a widened, realigned, cable-stayed suspension bridge of modern design. Despite years of research and consultation with experts worldwide, the Conservancy and others could not find a way to halt or reverse the alkali-silica reaction that is slowly destroying the bridge. The demise of the bridge will be a tremendous loss to the history and landscape of Los Angeles, and to the many Angelenos who care so deeply about this icon. Yet this regrettable outcome LEFT: Lincoln Place in Venice, threatened with demolition for nearly a decade until 2010. Photo by Ingrid E. Mueller. presents an important opportunity for the city UPPER RIGHT: Baldwin Hills Village (Village Green), a National Historic Landmark. Photo by Flora Chou/L.A. Conservancy. LOWER RIGHT: Threatened with demolition for years, Chase Knolls in Sherman Oaks was featured to look to the future without ignoring its past. on our Modern Committee’s “How Modern Was My Valley” tour in 2000. Photo from Conservancy archives. The Sixth Street Viaduct is the largest, last built, and most famous member of a Garden Apartments: remarkable collection of monumental bridges spanning the Los Angeles River. These bridges Design Fostering Community were designed to complement one another, making the collection a de facto historic district. -

Echo Park Los Angeles, Ca

1421-1427 W SUNSET BLVD ECHO PARK LOS ANGELES, CA ECHO PARK RETAIL INVESTMENT OPPORTUNITY Lorena Tomb Ty Del Re Principal Senior Associate OR POTENTIAL DEVELOPMENT SITE T: 213.277.7247 ext. 1 T: 213.277.7247 ext. 3 1 [email protected] [email protected] License #: 01894475 License #: 01947880 www.urbanlimeRE.com 1421-1427 1421-1427 W SUNSET BLVD W SUNSET BLVD LOS ANGELES, CA LOS ANGELES, CA OFFERING: Echo Park Retail Investment or Development Opportunity URBANLIME Real Estate is pleased to present the outstanding opportunity to pur-chase the fee simple interest at 1421 – 1427 W Sunset Boulevard. Located within walking distance to Dodgers Stadium the property consists of a vacant 5,055 square foot building on 13,253 square feet of land with approximately 127 feet of prime street frontage on Sunset Blvd in Echo Park. The property was previously used as retail and is zoned LAC2 which allows for a wide array of Table of Contents commercial uses. The zoning also allows for multi-family and mixed-use de- velopment in one of Los Angeles’s most desirable urban neighborhoods. Offering 3 Property Summary 3 Location 4 PROPERTY SUMMARY Area Highlights 4 Retail Opportunity 6 Address: 1421 -1427 West Sunset Boulevard, Financial Analysis 6 Los Angeles, CA 90026 Amenities Map 7 APN: 5406-010-041 Development Potential 8 Occupancy: 100% Vacant Development Map 9 Gross Building Area: 5,055 SF Features 9 Site Area: 13,253 SF Floorplan 9 Year Built: 1927 Frontage: 127FT Zoned: C2-1VL 2 3 1421-1427 W SUNSET BLVD LOS ANGELES, CA ECHO PARK LOCATION: • Set on the corner of Sunset & Quintero the property is located in the heart of Echo Park with high visibility, heavy trafic, strong retail and a local community consisting of a dense collection of single & multi-fam- ily homes. -

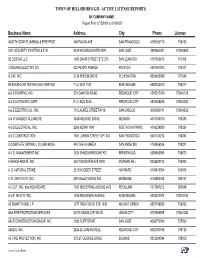

ACTIVE LICENSE REPORTS by COMPANY NAME Report from 5/15/2021To 8/10/2021

TOWN OF HILLSBOROUGH - ACTIVE LICENSE REPORTS BY COMPANY NAME Report From 5/15/2021to 8/10/2021 Business Name Address City Phone License Nb \NORTH STAR PLUMBING & FIRE PROT 466 FAXON AVE SAN FRANCISCO 4155190710 708153 2001 SECURITY SYSTEMS & E.W. 4529 HOUNDS HAVEN WAY SAN JOSE 4082662001 0708-0840 3E DESIGN, LLC 1933 DAVIS STREET STE 270 SAN LEANDRO 5107356475 707304 4 SQUARE ELECTRIC CO. 523 PERRY AVENUE PACIFICA 6507661303 706077 4LEAF, INC. 2126 RHEEM DRIVE PLEASANTON 9254625959 707548 55 BACKFLOW TESTING AND SERVICE P. O. BOX 1162 BURLINGAME 6505183810 706317 A & B ROOFING, INC. 572 CANYON ROAD REDWOOD CITY 6505517029 0708-0215 A & D AUTOMATIC GATE P. O. BOX 5040 REDWOOD CITY 6503658828 0708-0352 A & E ELECTRIC CO., INC. 751 LAUREL STREET #719 SAN CARLOS 6505939111 0708-0822 A & M WONDER CLEANERS 36339 BEATKE DRIVE NEWARK 6507035010 708288 A & Q ELECTRICAL, INC. 2266 KENRY WAY SOUTH SAN FRANC 4156239930 708324 A B Z CONSTRUCTION 1501 LARKIN STREET APT 304 SAN FRANCISCO 6507734213 708284 A COMPLETE DRYWALL CO DBA MICHA 443 THE ALAMEDA SAN ANSELMO 4154569306 708321 A K D MANAGEMENT INC 2526 SHADOWBROOKE RD BRENTWOOD 6505565599 708073 A SHADE ABOVE, INC. 350 WOODVIEW AVE #200 MORGAN HILL 8333609100 706982 A. G. NATURAL STONE 23139 KIDDER STREET HAYWARD 5108878359 003918 A. R. GROTH CO, INC. 200 VALLEY DRIVE #53 BRISBANE 4154683365 002787 A.C.C.P. INC. dba AQUASCAPE 1120 INDUSTRIAL AVENUE # 23 PETALUMA 7077697212 003548 A.V.R. REALTY, INC. 1169 BROADWAY AVENUE BURLINGAME 6503422073 0708-0196 A3 SMART HOME, LP 1277 TREAT BLVD STE 1000 WALNUT CREEK 9252748580 708293 AAA FIRE PROTECTION SERVICES 30113 UNION CITY BLVD. -

Incentives for the Preservation of Historic Homes (2004)

Incentives for the Preservation and Rehabilitation of Historic Homes in the City of Los Angeles A Guidebook for Homeowners Incentives for the Preservation and Rehabilitation of Historic Homes in the City of Los Angeles A Guidebook for Homeowners The Getty Conservation Institute Contents Preface v Introduction vi An Overview of Incentives, Loan Programs, and Grants x for Buying and Rehabilitating Historic Homes Historic Preservation Incentive Programs for Homes 1 Designated at the Local, State, or Federal Level Tax Incentives 2 Mills Act Historical Property Contract 3 Historic Resource Conservation Easement 10 Regulatory Relief 12 California Historical Building Code 12 Zoning Incentives 14 Your Home as a Film Location 15 Commercial Loan Programs for Homeownership 17 and Home Renovation Loans and Mortgages 18 Commercial Lenders and the Public Sector 19 Home Renovation Loans 21 Reverse Mortgages for Seniors 24 Programs for Low- and Moderate- Income 25 Homebuyers and Homeowners Affordable Mortgage Products 28 HUD’s Federal Housing Administration Loans 28 Nonprofit Organizations Working for Affordable Housing 28 California Housing Finance Agency 30 Municipal Programs for Low- and Moderate-Income 31 Homebuyers and Homeowners Programs for Low-Income Homeowners and Homebuyers 31 Programs for Moderate-Income Homebuyers 34 Los Angeles Community Redevelopment Agency 35 State of California Department of Insurance Earthquake 37 Grant Program Historic Preservation Incentives in Other Cities and States 39 Permit Fee Waivers 40 Sales Tax Waivers 40 Revolving