Drafting the Fdd for Multiple Or Otherwise Complex Offerings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Level 1 Level 2

I-10 13 1 2 4 6 7 8 9 10 12 B 5 1 B 1 11 11 2 E C 3 4 12 3 8 VINCENT AVENUE 1 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 4 5 6 7 9 10 11 K19 5 D K1 K2 K3 K4 K7 K8 K10 K11 K12 K13 K15 K16 K17 K18 CC 6 13 26 22 21 20 17 16 15 14 27 25 24 19 18 17 16 15 7 8 9 10 11 12 19 18 K9 23 22 21 20 28 14 K21 K22 K23 K24 13 28 27 17 16 A 26 25 24 23 22 19 15 14 13 D 21 20 10 LEVEL 1 9 Garage Garage 8 3 Levels 3 Levels 7 6 5 1 4 E 3 29 30 31 Firestone WEST COVINA PARKWAY 7 8 6 H 23 F G 5 9 4 Food 10 Court 10 12 3 4 5 9 1 2 3 5 6 7 1 1314 2 6 7 8 1 2 J 3 21 K25 K26 K28 K29 K30 K30 K31 4 5 6 8 9 10 16 15 14 13 12 11 10 9 8 22 21 20 16 15 14 13 12 20 17 19 18 17 21 K34 11 20 19 18 17 16 14 13 12 19 18 F H Garage Garage LEVEL 2 3 Levels 3 Levels Restrooms / Baños Security / Seguridad Mall Office / Oficina ATM / Cajero Automático Food / Comidas Play Space Family Lounge Stroller Rental Amazon Locker Volta Charging Stations Area de Juego para Niños Salón Familiar Carrito de Rentar Elevator / Elevador Escalator / Escaleras Mall Entry / Entrada Parking / Aparcamiento APPAREL — WOMEN’S ATHLETIC APPAREL & EQUIPMENT K2 Doc Popcorn/Dippin’ Dots MATERNITY & BABY H15 12PM A16 ARZA Soccer C23 Green Crush D9 H&M Kids A9 Aèropostale A7 Cap City E13 Jamba Juice Macy’s, Destination Maternity H15 Austin 5 A6 Champs Sports K19 Lollicup H3 Boarders J19 Foot Locker F9 Mrs. -

E:Kx:!Alilur \ 877.750.5464

E:Kx:!aliLur \ 877.750.5464 PARKING GARAGE Las Vegas IVIaps Visit us at: http:/Awww.lasvegasmaps.com LTTXOR U.0006 LOWER LEVEL ELEVATORS Las Vegas Maps Visit us at: http://www.iasvegasmaps.com ATTRACTIONS DINING LUXOR ELEVATORS ENTERTAINMENT NIGHTLIFE SPA AND POOL ABX American Burger Works E9 The Atrium Showroom LI 7 Aurora L19 Attraction & StiowTicl<ets L2 Backstage Deli l-so ELEVATOR 1 Nurture Spa and Salon L46 BucadiBeppo E19 Menopause The Musical® Centra Bar & Lounge L25 BODIES... Ttie Exhibition Li Blizz Frozen Yogurt and Desserts la Floors 1 -5 Oasis Pool L48 Dairy Queen/Orange Julius E16 Carrot Top Flight L22 SCORE! IM Food Court lb Floors 22-30 Titanic: The Artifact Exhibition i.3 Bonnano's Pizzeria, L.A. Subs and Salads, Dick's Last Resort E10 FANTASY LAX Nightclub/Savile Row L24 Drenched Pool E36 ELEVATOR 2 McDonald's, Nathan's Famous Hot Dogs, Drenched Clubhouse E4 CRISSANGEL*" Believe'" MB The Spa at Excalibur ESS 2 Floors 6-15 Fun Dungeon El Original Chicken Tender Company, Starbucks Coffee Excalibur Buffet E12 Theatre & Box Office ELEVATOR 3 Arcade and Midway MORE The Buffet (Lower Level) The Steakhouse at Camelot E14 3a Floors 1 -5 Box Office E16 Public House Food Court E15 3b Floors 16-21 Thunder Showroom E17 Pyramid Cafe Auntie Anne's Pretzels, Big Chill Daiquiri Bar, Tournament of Kings Showroom E18 Rice & Company ; Cinnabon, Hot Dog on a Stick, Krispy Kreme; ELEVATOR 4 M life Desk !fi Starbucks (Three Locations) McDonald's, Pick up Stix, Pizza Hut, Popeyes, 4a Floors 1-5 Poker Room T&T (Tacos & Tequila) Popcornopolis, Starbucks Coffee, 4b Floors 6-15 M life Desk E6 T&T (Tacos & Tequila) Daiquiri Bar Tropical Smoothie E3 Poker Room E2 TENDER'^ steak & seafood . -

1289130, 140 & 180 Southsan Jose, Californiapark Victoria Drive Milpitas, California

FOR SALELEASE 1289130, 140 & 180 SOUTHSAN JOSE, CALIFORNIAPARK VICTORIA DRIVE MILPITAS, CALIFORNIA 1289 S Park Victoria Dr PROPERTY HIGHLIGHTS + ±9,094 SF + Corner Location at Signalized Location + Anchored by Comerica Bank (NYSE: CMA) + Walking Distance to Nearby Retail with Enclosed Walk Up ATM Amenities + Great Investor or User (SBA) Opportunity + Great Access to Highway 680 + Ground Floor: 4,450 SF (49%) + Building Signage Available – Leased to Comerica Bank + Parking Ratio: 4/1,000 SF (LED: 12/31/24) (35 On-Site Parking Spaces) + 2nd Floor: 4,644 SF (51%) + Parcel Size 22,521 SF – To be Delivered Vacant + APN: 088-36-035 CONTACT US VINCE MACHADO ANTHONY PODESTA Senior Vice President Associate Lic. 01317553 Lic. 01467260 +1 408 453 7411 +1 408 453 7479 [email protected] [email protected] www.cbre.us/siliconvalley 1289 S PARK VICTORIA DR FOR SALE Milpitas, California FLOOR PLAN 1st FLOOR ±4,450 SF Leased to Comerica Suite 100 ±4,450 SF VACANT VACANT Suite 200 Suite 205 ±1,662 SF ±751 SF 2nd FLOOR ±4,644 SF Suite 201 ±2,231 SF VACANT © 2018 CBRE, Inc. This information has been obtained from sources believed reliable. We have not verified it and make no guarantee, warranty or representation about it. Any projections, opinions, assump- tions or estimates used are for example only and do not represent the current or future performance of the property. You and your advisors should conduct a careful, independent investigation of the property to determine to your satisfaction the suitability of the property for your needs. N:\Team-Marketing\1289 S Park Victoria Drive\1289_S_ParkVictoria_Flyer_V04.indd Photos herein are the property of their respective owners and use of these images without the express written consent of the owner is prohibited. -

Level 2 Level 1

LEVEL SPACE # LEVEL SPACE # APPAREL The Blessed Life ............................................................................1 nF-09 Icing ..................................................................................................1 n C-02 Charlotte Russe ............................................................................2 n K-02 Island Expressions Jewelry .......................................................2 n H-05 Cookies Clothing Company .....................................................1 n E-02A JYL Jewelry .....................................................................................1 n F-01A Hot Topic .........................................................................................2 n M-07A Kay Jewelers ..................................................................................1 n A-08 Jeans Warehouse .........................................................................1 n E-03 N. Cat Costume Fashion Jewelry ............................................1 n F-04 Know1..............................................................................................2 n L-05 Zales Jewelers ...............................................................................1 n E-07 n H-09 Local Motion .................................................................................2 M-09 -02 G- A G 10 H-0 1 H-08 OFFICE SUPPLIES Mayjah League Clothing ...........................................................1 n G-03 G- 01 G-09 H- H-06 07 paper, pens, etc. by Conrad .....................................................2 -

Hayward Dining Guide

Hayward Dining Guide Restaurants, Eateries, Coffee & More Welcome to the City of Hayward! Sharing a meal with family and friends is a social event and when the food is really good, a celebration. The diversity of restaurants in Hayward reflects this community and acknowledges the many cultures thriving in the ‘Heart of the Bay.’ Going to a new restaurant is one of the easiest and fun ways to try something new: It’s the exotic without the airfare, the comfort without the commitment, the fallback when the refrigerator is empty. Please use this guide to support our local restaurants and economy. If you have any additions or changes, please contact the City’s Economic Development Department by calling 510‐583‐5540 or by emailing Economic.Development@hayward‐ca.gov. Enjoy! Afghan Kabul Afghan Restaurant* 24046 Hesperian Blvd 510 293‐3093 African Kupe Studio Restaurant & Lounge 943 B St. 510 576‐3234 American Anna's Coffee Shop 444 Jackson St 510 582‐9185 Applebee's Neighborhood Grill & Bar 24041 Southland Dr 510 782‐1002 Buddy’s Bites and Brews 24277 Hesperian Blvd 510 401‐5999 Carmen & Family Bar‐B‐Q 692 W A St 510 887‐1979 Chaparral Grill 303 Southland Mall Dr 510 760‐4328 Coco’s 20413 Hesperian Blvd 510 782‐5686 City Bistro* 30162 Industrial Pkwy SW 510 429‐8600 Country Waffles Hayward 30182 Industrial Pkwy SW 510 429‐9100 Crabaholic #2 24375 Southland Dr 510 887‐8999 Denny’s* 30163 Industrial Pkwy SW 510 471‐0311 Digger’s Diner 217 W Winton Ave 510 470‐3664 Elephant Bar Restaurant 24177 Southland Dr 510 266‐0400 Emil Villa’s 24047 Mission -

Portland Crossing 2030 W U.S

1 Portland Crossing 2030 W U.S. Hwy 181 Portland, TX 78374 2 SANDS INVESTMENT GROUP EXCLUSIVELY MARKETED BY: BLAKE DAVIS TONY BARRERA Lic. # 632214 Lic. # 676109 512.543.4647 | DIRECT 512.768.0213 | DIRECT [email protected] [email protected] 305 Camp Craft Rd, Suite 550 Westlake Hills, TX 78746 844.4.SIG.NNN www.SIGnnn.com In Cooperation With Sands Investment Group Austin, LLC Lic. #9004706 BoR: Max Freedman - TX Lic. # 644481 SANDS INVESTMENT GROUP 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS 04 06 09 15 17 INVESTMENT OVERVIEW LEASE ABSTRACT PROPERTY OVERVIEW AREA OVERVIEW TENANT OVERVIEW Investment Summary Rent Roll & Financials Property Images City Overview Tenant Profiles Investment Highlights Sold/On Market Comparables Location, Aerial & Retail Maps Demographics © 2021 Sands Investment Group (SIG). The information contained in this ‘Offering Memorandum’, has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable. Sands Investment Group does not doubt its accuracy; however, Sands Investment Group makes no guarantee, representation or warranty about the accuracy contained herein. It is the responsibility of each individual to conduct thorough due diligence on any and all information that is passed on about the property to determine its accuracy and completeness. Any and all proJections, market assumptions and cash flow analysis are used to help determine a potential overview on the property, however there is no guarantee or assurance these proJections, market assumptions and cash flow analysis are subJect to change with property and market conditions. Sands Investment Group encourages all potential interested buyers to seek advice from your tax, financial and legal advisors before making any real estate purchase and transaction. -

Pocket Guide to Low Sodium Foods

CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .............................................................................7 Use Less Salt ...............................................................................8 Tips to Reduce Salt ....................................................................8 Become Sodium Conscious ............................................................9 Foods High in Sodium ................................................................9 Note to the Hypertensive ............................................................. 10 FOOD LABELING GUIDELINES ...................................................... 12. What the Label Tells You .............................................................. 12. Nutritional Content Claims ........................................................... 13. Calories and Nutrients ................................................................ 13. DINING OUT ................................................................................ 17 USING THIS GUIDE ...................................................................... 18 Nutritive Criteria ........................................................................ 19 Author’s Note ............................................................................. 2.0 Abbreviations and Symbols ......................................................... 2.1 Food Measurements and Equivalents ............................................. 2.1 Reading the Nutritive Values ........................................................ 2.2. PART 1 – GROCERY -

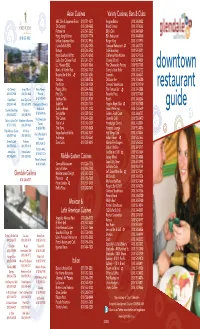

Resturant Map 2013 2/27/13 9:12 AM Page 1

Resturant Map 2013 2/27/13 9:12 AM Page 1 Asian Cuisines Variety Cuisines, Bars & Clubs ABC Chin & Japanese Food (818) 551-1677 Angelas Bistro (818) 240-0382 Chi Dynasty (818) 500-9888 Brand Terrace (818) 242-6565 Fortune Inn (818) 547-2832 Billy’s Deli (818) 246-1689 (818) 637-8982 Hong Kong Kitchen (818) 247-7774 BJ’s Restaurant (818) 844-0160 Ichiban Japanese Rest. (818) 242-9966 Burger King (818) 247-1914 I Love Tofu & BBQ (818) 242-0505 Carousel Restaurant (818) 246-7775 Katsuya (818) 244-5900 Café Broadway (818) 549-0311 Kyoto Seafood Buffett (818) 243-8168 California Pizza Kitchen (818) 507-1558 Lucky Star Chinese Food (818) 241-0211 Charles Billiard (818) 547-4859 L.L. Hawaiin BBQ (818) 637-8566 The Cheesacake Factory (818) 550-7505 Max’s of Manila Rest. (818) 637-7751 Clancy’s Crab Boiler (818) 242-2722 downtown Noypitz Bar & Grill (818) 247-6256 Conrad’s (818) 246-6547 Octopus (818) 500-8788 DA Juice Bar (818) 243-6200 Panda Inn (818) 502-1234 Damon’s Steakhouse (818) 507-1510 Chi Dynasty Jersey Mike's Richie Palmer's restaurant Peking China (818) 244-9888 The Famous Bar (818) 241-2888 (818) 500-9888 (818) 281-4888 Pizzeria Pho City (818) 555-3888 Favorite Place (818) 507-7409 CrepeMaker Jewel City Diner (818) 240-4440 Sedthee Thai (818) 247-9789 Foxy’s (818) 246-0244 (818) 243-1445 (818) 637-8998 Starbucks at Barnes & Sushi Kai (818) 243-7393 Giggles Night Club (818) 500-7800 guide Crumbs Bake Shop Katsuya Noble Café Sushi on Brand (818) 241-0133 Great White Hut (818) 243-5619 (818) 502-0050 (818) 244-5900 (818) 545-9146 Teriyaki -

For Fast Food

For Fast Food ... stop at one of the 99 nation-wide Fast Food chains in today's grid--but do not Super-Size it! A R C T I C C I R C L E E B R K P E O K M Z A D Y P P A H E O P S H A K E Y S P I Z Z A Z O S D U S N G O D T O C S F O & S S O T N E K C I H C R M I A S J B S L E Z T E R P S L E Z T E W T T H C I S I I P R E R A A I A L T K Y R E S S O N Y O M K S A E B E H O O R N T M O S V O S N L S U E P C S G R N D B T G T F A E G I E L E E G S I Z W K A G I S G P G E O P Y O B N U B U F K L R P C L T C G U A L I I D L R R A O R T U H A Z Z I P R N L N L E O N I A R Z O A N B T S E G L J P E W T A S P I D H L O E S Y A T R T W R A A R O O U G S K A X M I G H T Y T A C O N D H H S T L T R S S X O T Y I G N Z C E S U L O W I R S N J G E N O A A S E E O A L B D H L O H O K A H O K A B E N T O O J O O I U K N T K I P T B Y S U E H R I D T L A Q O S S S E E O F A H K S E D E R U B I O S J R R G N N E T D R L E Z T I N H C S R E N E I W A C N N R P E O T I T A E L A O S U E A G A N I R A M B U S E I K H S A R G U O R H P B K T T R H T A T R S R S R B S Q D E M C & E N S N O S N E W S P C A R L S J R S I G O B A E Y T I S H H P A E A Q D O B A M E X I C A N G R I L L N N T U R N N L E E W O A R F D C O A C R N T H O E N T I V S L Y C I I C S E E E O O T O A S C X D S H N E K C I H C R E E N O I P A K T K B F H M R A H Z F I L I B E R T O S E E D R A H E S N D U E R U S I C N K T L Z K F T E T R N A T H A N S F A M O U S Z I H R E C H E U S O N I E V I R D S R E K C E H C E C N V U A N I G D L G W K J C K P P F E S V A X P J I R E R T L I R B T -

Professional Office Suites for Lease at Victoria Gardens 12505 & 12487 N

G. CHAFFEY BUILDING AT CHAFFEY TOWN SQUARE PROFESSIONAL OFFICE SUITES FOR LEASE AT VICTORIA GARDENS 12505 & 12487 N. MAINSTREET | RANCHO CUCAMONGA, CA Office Suites Situated Above the Best Retail Amenities in the Inland Empire New Owner, Brookfield Properties, is a Global Leader in Premier Real Estate Portfolio Management, with a Focus on Maximizing the Tenant Experience. DAVID MUDGE LINDSAY MINGEE 951.276.3611 951.276.3622 [email protected] [email protected] DRE# 01070762 DRE# 01920658 No warranty or representation has been made to the accuracy of the foregoing information. Terms of sale or lease and availability are subject to change or withdrawal without notice. Lee & Associates Commercial Real Estate Services, Inc. - Riverside. 3240 Mission Inn Avenue - Riverside, CA 92507 | Corporate DRE# 01048055 REV: 06/29/20 G. CHAFFEY BUILDING AT CHAFFEY TOWN SQUARE PROFESSIONAL OFFICE SUITES FOR LEASE AT VICTORIA GARDENS NOW OWNED & MANAGED BY BROOKFIELD PROPERTIES 12505 & 12487 N. MAINSTREET | RANCHO CUCAMONGA, CA 12505 N. Mainstreet (W. Chaffey Building) Suite 220 1,749 RSF Fully Built Out Office Suite Suite 225 1,217 RSF Fully Built Out Office Suite Suite 222/225 2,966 RSF Combined Square Footage $2.50 PSF, Full Service Gross 12487 N. Mainstreet (G. Chaffey Building) Suite 250 3,414 RSF Vanilla Shell with Open Floor Plan Cold Shell with Excellent Views, Ready Suite 256 5,689 RSF for Custom Design Fully Built Out Office W/Kitchen Suite 260 2,230 RSF Available September 1, 2020 $2.50 PSF, Full Service Gross DEPARTMENT STORES Jos. A. Bank Clothiers 28 646-8521 HEALTH & BEAUTY Luna Modern Mexican Kitchen 29 334-4444 Lucky Brand Jeans 8 463-4006 2% Chop 38 922-8080 PARKING PARKING JCPenney 646-8911 The Melt 27 Coming Soon ATM Management Office Macy’s 646-3333 Oakley 16 899-3056 bareMinerals 28 463-6369 P.F. -

Spring 2014 Newsletter Shop to Help Your School

SPRING 2014 NEWSLETTER SHOP TO HELP YOUR SCHOOL EARN $700 TO $5,000 SHOP & LOG RECEIPTS TO HELP SPRING IS FASHION YOUR SCHOOL EARN UP TO $5,000! Earn 500 points per dollar spent at Lexy and Image Visit our new and expanded women’s fashion retailers at Lower Level near Bring your original receipts from purchases made at Moreno Crunch Fitness. Valley Mall since May 1, 2013 to the Mall Management Office, located on the Lower Level near Macy’s and open Earn Quadruple points per dollar spent at these selected stores: Monday - Friday, 8:30am to 5pm. Receipts are logged, Spring Fashions: stamped and returned to the customer. Or, you may deposit Claire’s, Express, Forever 21, Hollister Co., Journeys, Justice, receipts you don’t need back (with your school name) any New York & Company, The Children’s Place, Torrid and Zumiez time in the Earning 4 Learning collection box, located on the Gifts, Fun & Games: Lower Level near Macy’s and Harkins Theatre. Your school Bath & Body Works, Crunch Fitness, FYE, Radio Shack, Round 1 earns at least five points for each dollar spent at any store, and Things Remembered restaurant and service provider at Moreno Valley Mall. Earn Double points per dollar spent at these selected eateries: Did you receive a receipt via email? Boba Express, Burger & Grill, Chinese Gourmet Express, Cinnabon, Visit shoppingpartnership.com/morenovalley to submit a Dairy Queen/Orange Julius, Hometown Buffet, Hot Dog on a Stick, receipt emailed to you from a retailer. Kelly’s Coffee and Fudge Factory, Mrs. Fields Cookies, PretzelMaker, Questions? Sansei, Sbarro Italian Eatery, Subway and Sweet Factory Call (800) 539-3273 or visit MorenoValleyMall.com. -

Restaurant Inspection Scores Since 4/20/15

Restaurant Inspection Scores since 4/20/15 FACILITY NAME SITE ADDRESS CITY ACTIVITY SCORE DATE 10TH & M SEAFOODS 301 MULDOON RD ANCHORAGE 7/22/2015 100 10TH & M SEAFOODS 301 MULDOON RD ANCHORAGE 12/28/2016 92 12-100 COFFEE & 12100 OLD SEWARD ANCHORAGE 1/27/2017 100 COMMUNITIES HWY 12-100 COFFEE & 12100 OLD SEWARD ANCHORAGE 4/29/2015 94 COMMUNITIES HWY 12-100 COFFEE & 12100 OLD SEWARD ANCHORAGE 2/17/2016 97 COMMUNITIES HWY 3 NORTH MARKET - BP 3rd 900 E BENSON BLVD 3rd ANCHORAGE 1/14/2016 100 Floor 49TH STATE BREWERY 717 W 3RD AVE ANCHORAGE 8/8/2016 94 49TH STATE BREWERY - 717 W 3RD AVE ANCHORAGE 8/8/2016 96 BAR 5TH AVENUE DELI 320 W 5TH AVE 410 ANCHORAGE 11/4/2015 90 5TH AVENUE DELI 320 W 5TH AVE 410 ANCHORAGE 10/21/2016 91 88TH ST PIZZA 2300 E 88TH AVE ANCHORAGE 4/12/2016 94 88TH ST PIZZA 2300 E 88TH AVE ANCHORAGE 3/22/2017 95 88TH ST PIZZA 2300 E 88TH AVE ANCHORAGE 5/6/2015 97 907 SWEETS 1600 GAMBELL ST ANCHORAGE 10/10/2016 100 907 WINGMAN 3505 SPENARD RD C1&2 ANCHORAGE 11/1/2016 95 A CUP ABOVE 5737 OLD SEWARD HWY ANCHORAGE 7/29/2015 99 A CUP ON THE RUN 1402 INGRA ST ANCHORAGE 10/27/2016 99 A CUP ON THE RUN 1402 INGRA ST ANCHORAGE 12/30/2015 97 A D FARM 825 L ST ANCHORAGE 3/2/2016 98 A SAUCE COMPANY 825 L ST ANCHORAGE 7/2/2016 100 A SAUCE COMPANY 825 L ST ANCHORAGE 7/2/2016 100 A SLICE OF HEAVEN - M 6920 BAXTER TERRACE ANCHORAGE 4/25/2016 98 A TASTE OF THAI 11109 OLD SEWARD ANCHORAGE 12/2/2015 100 HWY 6 A WHOLE LATTE LOVE 4000 W DIMOND BLVD ANCHORAGE 4/6/2017 100 A WHOLE LATTE LOVE 4000 W DIMOND BLVD ANCHORAGE 5/28/2015 98 A WHOLE LATTE