Case Based Urology Learning Program

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

This Document Was Released in November 2020. This Document Will Continue to Be Periodically Updated to Reflect the Growing Body of Literature Related to This Topic

MEDICAL STUDENT CURRICULUM This document was released in November 2020. This document will continue to be periodically updated to reflect the growing body of literature related to this topic. Help: Andrew Gusev - [email protected] MALE INFERTILITY KEYWORDS: infertility, azoospermia, oligospermia, semen analysis, varicocele LEARNING OBJECTIVES: At the end of medical school, the medical student will be able to… 1. Describe the hypothalamus-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis 2. Describe the workup for male infertility, including the importance of the physical exam 3. Restate the limitations of the semen analysis 4. List some common reversible causes of infertility and their treatments 5. Recognize when to refer a patient for ART Introduction Approximately 15% of couples will be unable to conceive after attempting unprotected intercourse for one year. Of these couples, about 50% of them will have some male factor to that is contributing to their infertility (a male factor is the sole reason in approximately 20% of infertile couples). (Thonneau P, 1991) Male infertility can be due to a variety of genetic, anatomic, and environmental conditions, many of which will be briefly discussed below. When a cause for an abnormal semen analysis cannot be found, it is termed idiopathic. When a man is infertile with a normal semen analysis and workup, the term unexplained infertility is used. As the word suggests, these men do not have a known cause for their infertility but it is thought to likely be due genetic defects that have not been described yet. The purpose of evaluation is to identify possible conditions causing infertility and treating reversible conditions which may improve a man’s fertility potential. -

Role of Nutrition and Associated Factors in Oligospermia (Low Sperm

The Pharma Innovation Journal 2019; 8(3): 68-72 ISSN (E): 2277- 7695 ISSN (P): 2349-8242 NAAS Rating: 5.03 Role of nutrition and associated factors in oligospermia TPI 2019; 8(3): 68-72 © 2019 TPI (Low sperm count) www.thepharmajournal.com Received: 09-01-2019 Accepted: 13-02-2019 Neelesh Kumar Maurya Neelesh Kumar Maurya Department of Home Science, Abstract Bundelkhand University, Jhansi, Prevalence of infertility gravitates to increase due to different factors. Causes of male infertility could be Uttar Pradesh, India varicocele, idiopathic infertility, testicular insufficiency, obstruction, ejaculation disorder, medicine- radiation effect, undescended testis, immunological mechanisms, endocrine dysfunction such as diabetes, excessive taking of alcohol, smoking and environmental toxins such as pesticides, mercury and lead. It is furthermore understood that person, obesity, be deficient in of nutrition and habits of utilizing time for example too much use of, laptop, mobile phones, computers and sauna, etc., as for women, age, smoking, too much consumption of alcohol, having a skinny or overweight body and having been exposed to physical or mental stress fruition in amenorrhea might be the causes of infertility. The progress in infertility prevalence draws attention to the effects of factors such as lifestyle, dietetic habits and environmental factors. Male infertility originates from mostly as a result of the association between oxidative stress and antioxidants. A review of these areas will provide researchers with a more noteworthy understanding of the compulsory participation of these nutrients in male reproductive processes. This review also caustic out gaps in recent studies which will require further investigations. Keywords: Nutrition; spermatogenesis, oligospermia, infertility, antioxidants, reproductive Introduction An approximately six per cent of adult males are thought to be infertile. -

Common and Uncommon Presentation of Fluid Within the Scrotal Spaces

THIEME E34 Review Common and Uncommon Presentation of Fluid within the Scrotal Spaces Authors V. Patil, S. M. C. Shetty, S. Das Affiliation Radiodiagnosis, JSS Medical College, Mysore, India Key words Abstract gin. US may suggest a specific diagnosis for a ●▶ US wide variety of intrascrotal cystic and fluid ▶ ▼ ● ultrasonography Ultrasonography(US) of the scrotum has been lesions and appropriately guide therapeutic ●▶ fluid demonstrated to be useful in the diagnosis of options. The paper reviews the current knowl- ●▶ testis ●▶ scrotum fluid in the scrotal sac. Grayscale US character- edge of ultrasound in conditions with fluid in the izes the lesions as testicular or extratesticular testis and scrotum. The review presents the and, with color Doppler, power Doppler and applications of ultrasonography in the diagnosis pulse Doppler, any perfusion can also be assessed. of hydrocele, testicular cysts, epididymal cysts, Cystic or encapsulated fluid collections are rela- spermatoceles, tubular ectasia, hernia and hema- tively common benign lesions that usually pre- toceles. The aim of this paper is to provide a pic- sent as palpable testicular lumps. Most cysts torial review of the common and uncommon arise in the epidydimis, but all anatomical struc- presentation of fluid within the scrotal spaces. tures of the scrotum can be the site of their ori- Introduction images with portions of each testis on the same ▼ image should be ideally acquired in grayscale and Scrotal conditions associated with fluid can be color Doppler modes. The structures within the received 21.01.2015 accepted 29.06.2015 broadly classified as fluid in scrotal sac, testicular scrotal sac are examined to detect extra testicu- cysts, epididymal cysts and inguinoscrotal hernia. -

Aspermia: a Review of Etiology and Treatment Donghua Xie1,2, Boris Klopukh1,2, Guy M Nehrenz1 and Edward Gheiler1,2*

ISSN: 2469-5742 Xie et al. Int Arch Urol Complic 2017, 3:023 DOI: 10.23937/2469-5742/1510023 Volume 3 | Issue 1 International Archives of Open Access Urology and Complications REVIEW ARTICLE Aspermia: A Review of Etiology and Treatment Donghua Xie1,2, Boris Klopukh1,2, Guy M Nehrenz1 and Edward Gheiler1,2* 1Nova Southeastern University, Fort Lauderdale, USA 2Urological Research Network, Hialeah, USA *Corresponding author: Edward Gheiler, MD, FACS, Urological Research Network, 2140 W. 68th Street, 200 Hialeah, FL 33016, Tel: 305-822-7227, Fax: 305-827-6333, USA, E-mail: [email protected] and obstructive aspermia. Hormonal levels may be Abstract impaired in case of spermatogenesis alteration, which is Aspermia is the complete lack of semen with ejaculation, not necessary for some cases of aspermia. In a study of which is associated with infertility. Many different causes were reported such as infection, congenital disorder, medication, 126 males with aspermia who underwent genitography retrograde ejaculation, iatrogenic aspemia, and so on. The and biopsy of the testes, a correlation was revealed main treatments based on these etiologies include anti-in- between the blood follitropine content and the degree fection, discontinuing medication, artificial inseminization, in- of spermatogenesis inhibition in testicular aspermia. tracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI), in vitro fertilization, and reconstructive surgery. Some outcomes were promising even Testosterone excreted in the urine and circulating in though the case number was limited in most studies. For men blood plasma is reduced by more than three times in whose infertility is linked to genetic conditions, it is very difficult cases of testicular aspermia, while the plasma estradiol to predict the potential effects on their offspring. -

Male Infertility

Guidelines on Male Infertility A. Jungwirth, T. Diemer, G.R. Dohle, A. Giwercman, Z. Kopa, C. Krausz, H. Tournaye © European Association of Urology 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE 1. METHODOLOGY 6 1.1 Introduction 6 1.2 Data identification 6 1.3 Level of evidence and grade of recommendation 6 1.4 Publication history 7 1.5 Definition 7 1.6 Epidemiology and aetiology 7 1.7 Prognostic factors 8 1.8 Recommendations on epidemiology and aetiology 8 1.9 References 8 2. INVESTIGATIONS 9 2.1 Semen analysis 9 2.1.1 Frequency of semen analysis 9 2.2 Recommendations for investigations in male infertility 10 2.3 References 10 3. TESTICULAR DEFICIENCY (SPERMATOGENIC FAILURE) 10 3.1 Definition 10 3.2 Aetiology 10 3.3 Medical history and physical examination 11 3.4 Investigations 11 3.4.1 Semen analysis 11 3.4.2 Hormonal determinations 11 3.4.3 Testicular biopsy 11 3.5 Conclusions and recommendations for testicular deficiency 12 3.6 References 12 4. GENETIC DISORDERS IN INFERTILITY 14 4.1 Introduction 14 4.2 Chromosomal abnormalities 14 4.2.1 Sperm chromosomal abnormalities 14 4.2.2 Sex chromosome abnormalities 14 4.2.3 Autosomal abnormalities 15 4.3 Genetic defects 15 4.3.1 X-linked genetic disorders and male fertility 15 4.3.2 Kallmann syndrome 15 4.3.3 Mild androgen insensitivity syndrome 15 4.3.4 Other X-disorders 15 4.4 Y chromosome and male infertility 15 4.4.1 Introduction 15 4.4.2 Clinical implications of Y microdeletions 16 4.4.2.1 Testing for Y microdeletions 17 4.4.2.2 Y chromosome: ‘gr/gr’ deletion 17 4.4.2.3 Conclusions 17 4.4.3 Autosomal defects with severe phenotypic abnormalities and infertility 17 4.5 Cystic fibrosis mutations and male infertility 18 4.6 Unilateral or bilateral absence/abnormality of the vas and renal anomalies 18 4.7 Unknown genetic disorders 19 4.8 DNA fragmentation in spermatozoa 19 4.9 Genetic counselling and ICSI 19 4.10 Conclusions and recommendations for genetic disorders in male infertility 19 4.11 References 20 5. -

Disorders of Ejaculation: an AUA/SMSNA Guideline - American Urological Association

02.07.2020 Disorders of Ejaculation: An AUA/SMSNA Guideline - American Urological Association Home Guidelines Clinical Guidelines Disorders of Ejaculation Disorders of Ejaculation: An AUA/SMSNA Guideline Panel Members Alan W. Shindel MD, Stanley E. Althof, Ph.D., Serge Carrier, MD, Roger Chou, MD, FACP, Chris G. McMahon, MD, John P. Mulhall, MD, Darius A. Paduch, MD, Ph.D., Alexander W. Pastuszak, MD, Ph.D., David Rowland, Ph.D., Ashely H. Tapscott, MD , Ira D. Sharlip MD. Executive Summary Ejaculation and orgasm are distinct but simultaneous events that occur with peak sexual arousal. It is typical for men to have some control over the timing of ejaculation during a sexual encounter. Men who ejaculate before or shortly after penetration, without a sense of control, and who experience distress related to this condition may be diagnosed with Premature Ejaculation (PE). There also exists a population of men who experience difficulty achieving sexual climax, sometimes to the point that they are unable to climax during sexual activity; these men may be diagnosed with Delayed Ejaculation (DE). While up to 30% of men have self- reported PE, few of these men have an ejaculation latency times (the time between penetration and ejaculation) of less than two minutes, making the actual prevalence of clinical PE and DE less than 5%.1, 2 Regardless, the experience of many clinicians suggest that the problem is not rare and can be a source of considerable embarrassment and dissatisfaction for patients. Data on the prevalence of DE are more limited, but a proportion of epidemiological studies report that men have difficulty achieving orgasm.3 Disturbances of the timing of ejaculation can pose a substantial impediment to sexual enjoyment for men and their partners. -

Herbal-Treatment-Common-Diseases

ORGANISATION OUEST AFRICAINE DE LA SANTE BOBO-DIOULASSO (BURKINA FASO) Tel. (226) 20 97 57 75/Fax (226) 20 97 57 72 E-mail : [email protected] - Site web: www.wahooas.org Herbal Treatment of Common Diseases in West Africa Bobo-Dioulasso, Décembre 2011. 1 Contents Page Introduction .............................................................................................................................5 Sickle cell anaemia .................................................................................................................. 6 HIV/AIDS ................................................................................................................................. 9 Tuberculosis ..........................................................................................................................13 Malaria ..................................................................................................................................14 Diabetes ................................................................................................................................16 Arterial hypertension ............................................................................................................. 19 Asthma ..................................................................................................................................21 Azoospermia .........................................................................................................................23 Gallstones .............................................................................................................................24 -

EFFECT of ARGININE on OLIGOSPERMIA* Llce to Endo- ADNAN MROUEH, M.D

FERTILITY AND 8TmRJLITY Vol. 21, No. 3, March 1970 ol. 21 Copyright © 1970 by The Williams & Wilkins Co. Primed in U.S.A . Aust :mato EFFECT OF ARGININE ON OLIGOSPERMIA* llce to Endo- ADNAN MROUEH, M.D. ;IMBEL Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, American University of Beirut, Beirut, Lebanon atozoa :enesis. Several amino acids have been detected the same experienced technician. Semen Work in human semen. They have been implied specimens were obtained by masturbation iology. to play a role in spermatozoal motility.2 after abstinence of at least 3 days. The analysis included observation on volume of cervi Among invertebrates the addition of any n. Ob- one of a number of amino acids and pep ejaculate number of spermatozoa, motil tides to spermatozoa extends their dura ity, and morphology. Twenty-four patients l10mas, tion of motility .11 Several amino acids underwent open testicular biopsy and the have been used to treat cases of oligo tissue was fixed in Bouin's solution. Brtility spermia and asthenospermia with vary Patients were given 2 gm. of arginine 1. Pre ing degrees of success. Of the amino acids hydrochloride daily for 10 weeks. The Fertil- utilized for this purpose, arginine has re treatment was started generally around 2 57. ceived enthusiastic acceptance.7 Out of 21 months after the biopsy to rule out any ~fertile patients reported by Ishigami,5 19 showed local injurious effects of the biopsy. At a favorable response and 5 pregnancies the end of the treatment period semen ensued. Similarly, Bernard/ Tanimura,1° count was obtained and again 1 month and Giarola and Agostini3 reported en after that. -

Infertility, Male : Article by Jonathan Rubenstein, MD 04.11.03 08:05

eMedicine - Infertility, Male : Article by Jonathan Rubenstein, MD 04.11.03 08:05 (advertisement) Home | Specialties | CME | PDA | Contributor Recruitment | Patient Education November 4, 2003 Articles Images CME Patient Education Advanced Search Link to this site Back to: eMedicine Specialties > Medicine, Ob/Gyn, Psychiatry, and Surgery > Quick Find Urology Author Information Introduction Clinical Rate this Article Infertility, Male Differentials Email to a Colleague Workup Last Updated: July 23, 2002 Treatment Synonyms and related keywords: ejaculate volume, sperm concentration, Medication Follow-up oligospermia, too few sperm, low sperm count, azoospermia, no sperm in the Miscellaneous ejaculate, sperm motility, sperm morphology, gonad, testis, testes, testicles, Pictures fertilization Bibliography Click for related AUTHOR INFORMATION Section 1 of 11 images. Author Information Introduction Clinical Differentials Workup Treatment Medication Follow-up Miscellaneous Pictures Bibliography Related Articles Adrenal Adenoma Author: Jonathan Rubenstein, MD, Staff Physician, Department of Urology, Northwestern University Medical School Adrenal Carcinoma Coauthor(s): Robert E Brannigan, MD, Assistant Professor, Department of C-11 Hydroxylase Urology, Northwestern Memorial Hospital Deficiency Jonathan Rubenstein, MD, is a member of the following medical societies: C-17 Hydroxylase American Urological Association Deficiency Cannabis Editor(s): Daniel B Rukstalis, MD, Chief, Associate Professor, Department of Compound Abuse Surgery, Division of Urology, -

Evaluation of Fertility Parameters in Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia Patients Treated with 5 Alph-Reductase Inhibitor (Finasteride) in Amara City/Iraq

Journal of Health, Medicine and Nursing www.iiste.org ISSN 2422-8419 An International Peer-reviewed Journal Vol.30, 2016 Evaluation of Fertility Parameters in Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia Patients Treated with 5 Alph-Reductase Inhibitor (Finasteride) in Amara city/Iraq Mokhtar Mohammed 1 Ahmed Khalifa 2 Nidhal Hashim 3* 1.Baghdad University, College of sciences for women. Baghdad. Iraq 2.Maysan University, College of sciences. Amara city, Iraq 3.Southern Technical University, Amara Technical Institute Department of Medical Laboratory. Amara city, Iraq Abstract The current study aimed to determine the fertility parameters among BPH patients before and after 3 months of taking 5-α reductase (finasteride) by seminal fluid analysis method, 60 patients and 30 healthy individuals as control group from Amara city ,were involved in this study, their ages were between (40-59)year old. They all subjected to direct seminal fluid analysis before and after 3 months of treatment by 5α-reductase(finasteride)(the healthy individuals didn’t take finasteride).The results showed that there is significant decreasing in volume (P˂0.05) in post-treatment group compared to pre-treatment and control group ,while the concentration of semen (count and total count) found to non-significantly decrease in post-treatment compared with pre-treatment and decreases significantly (P˂0.05) in comparison to control control group. On other hand, the Motility (high, moderate) observed to non significantly decreased in post-treatment group compared to pre-treatment group ,but significantly decreased (p<0.05) compared to control group, The Morphology (normal and abnormal ) found to non significantly differences between pre-treatment group and post-treatment group, but that were significantly differences in control group compared to pre-treatment and post-treatment group. -

The Study of Detecting Sperm in Testis Biopsy in Men with Severe Oligospermia and Azoospermia by Two Methods of Wet Prep Cytologic and Classic Histopathologic

Iranian Journal of Reproductive Medicine Vol.6. No.2. pp: 101-104, Spring 2008 The study of detecting sperm in testis biopsy in men with severe oligospermia and azoospermia by two methods of wet prep cytologic and classic histopathologic Houshang Babolhavaeji1 M.D., Seyed Habibollah Mousavi Bahar2 M.D., Nahid Anvari3 M.D., Ph.D., Farhang Abed1 M.D., Arash Roshanpour1 M.D. 1 Infertility Center, Fatemieh Hospital, Hamadan University of Medical Sciences and Health Services, Hamadan, Iran. 2 Besat Hospital, Hamadan University of Medical Sciences and Health Services, Hamadan, Iran. 3 Pathology Department, Fatemieh Hospital, Hamadan University of Medical Sciences and Health Services, Hamadan, Iran. Received: 15 December 2007; accepted: 22 May 2008 Abstract Background: Many azoospermic patients with non obstructive azoospermia (NOA) are candidate for testicular sperm extraction (TESE) and in vitro fertilization. Because sperm might be present in some but not all parts of the testes of such men, multiple sampling of testicular tissue are usually necessary to increase the probability of sperm finding. Sperm finding can be done by two methods: 1) classic histopathology and 2) wet smear. Objective: Comparative study of pathology and wet smear methods for discovering sperm in testis biopsy of azoospermic men. Materials and Methods: We prospectively studied 67 consecutive infertile men who referred to Fatemieh Hospital, Hamedan, Iran between April 2002 and September 2004. All patients were either azoospermic or severely oligozoospermic. They underwent intraoperative wet prep cytological examinations of testis biopsy material and then specimens were permanently fixed for pathologic examination too. Results: Among the 67 testes that underwent wet prep cytological examination, 44 (65.7%) were positive and 23 (34.3%) had no sperm in their wet smear. -

Significance of Testicular Microlithiasis

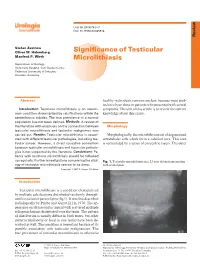

Urol Int 2005;75:3–7 DOI: 10.1159/000085918 Review Stefan Zastrow Oliver W. Hakenberg Signifi cance of Testicular Manfred P. Wirth Microlithiasis Department of Urology, University Hospital ‘Carl Gustav Carus’, Technical University of Dresden , Dresden, Germany Abstract healthy individuals remains unclear, because most stud- ies have been done in patients who presented with scrotal Introduction: Testicular microlithiasis is an uncom- symptoms. The aim of this article is to review the current mon condition characterized by calcifi cations within the knowledge about this entity. seminiferous tubules. The true prevalence in a normal population has not been defi ned. Methods: A review of the literature with emphasis on the connection between Morphology testicular microlithiasis and testicular malignancy was carried out. Results: Testicular microlithiasis is associ- Morphologically, the microliths consist of degenerated ated with different testicular pathologies, including tes- intratubular cells which form a calcifi ed core. This core ticular cancer. However, a direct causative connection is surrounded by a series of concentric layers. The outer between testicular microlithiasis and testicular patholo- gies is not supported by the literature. Conclusions: Pa- tients with testicular microlithiasis should be followed up regularly. Further investigations concerning the etiol- Fig. 1. Testicular microlithiasis in a 23 year old male presenting ogy of testicular microlithiasis remain to be done. with scrotal pain. Copyright © 2005 S. Karger AG, Basel Introduction Testicular microlithiasis is a condition characterized by multiple calcifi cations distributed randomly through- out the testicular parenchyma (fi g.1). It was fi rst described radiologically by Priebe and Garret [1] in 1970. The ap- pearance on ultrasound is typical with scattered multiple echogenic lesions distributed over the testis.