Joni Mitchell - A Chronology of Appearances v5.5 This work-in-progress lists all known appearances, drawn from a variety of sources. Researched, Compiled, and Maintained by Simon Montgomery, © 2001 Special thanks to Joel Bernstein for his contributions and assistance. Unless otherwise noted, appearances took place in the U.S. Appearances in Canada are denoted by city and province. Date format is YYYY.MM.DD Unconfirmed information is highlighted. Latest Update: May 23, 2021 Please send comments, corrections or additions to:

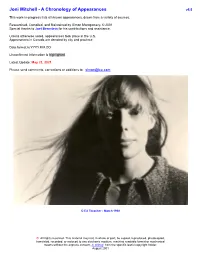

[email protected] © Ed Thrasher - March 1968 © All rights reserved. This material may not, in whole or part, be copied, reproduced, photocopied, translated, recorded, or reduced to any electronic medium, machine readable format or mechanical means without the express consent, in writing, from the specific lawful copyright holder. August 2001 1962 1962 Waskesiu Lake Waskesiu, SK According to Joni, “I started making music…in Saskatchewan mostly up at northern lakes, up around Lake Waskesiu … it was just self-entertainment with the gang then.” 1962.10.31 The Louis Riel Saskatoon, SK Joni’s first paid performance 1962.11.05 The Louis Riel Saskatoon, SK 1962.11.14 The Louis Riel Saskatoon, SK _______________________________________________________________________________ 1963 1963 The Louis Riel Saskatoon, SK Joni participated in weekly “Hoot Nights” playing her ukulele. 1963 Informal Recording - Radio Station CFQC-AM Saskatoon, SK 1963.08 For Men Only–CKBI-TV Prince Albert, SK Nineteen-year-old Joni Anderson was booked as a one-time replacement for a late-night moose-hunting show. During the program Joni was interviewed and performed several songs accompanying herself on baritone ukulele.