Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Female Lifestyle Factors and Risk Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sample-11060.Pdf

Ob/Gyn Sonography An Illustrated Review 2nd Edition Jim Baun, BS, RDMS, RVT, FSDMS Professional Ultrasound Services San Francisco, California SPECIALISTS IN ULTRASOUND EDUCATION, TEST PREPARATION, AND CONTINUING MEDICAL EDUCATION iv SPECIALISTSCopyright IN ULTRASOUND © 2016, EDUCATION, 2004 by Davies Publishing, Inc. TEST PREPARATION, AND CONTINUINGAll rights MEDICAL reserved. EDUCATION No part of this work may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, scanning, and recording, without prior written permission from the publisher. Davies Publishing, Inc. Michael Davies, Publisher Specialists in Ultrasound Education, Christina J. Moose, Editorial Director Test Preparation, and Continuing Charlene Locke, Production Manager Medical Education Janet Heard, Operations Manager 32 South Raymond Avenue Pasadena, California 91105-1961 Jim Baun, Illustration Phone 626-792-3046 Stephen Beebe, Illustration Facsimile 626-792-5308 Satori Design Group, Inc., Design Email [email protected] www.daviespublishing.com Notice to Users of This Publication: In the field of ultrasonography, knowledge, technique, and best practices are continually evolving. With new research and developing technologies, changes in methodologies, professional prac- tices, and medical treatment may become necessary. Sonography practitioners and other medi- cal professionals and researchers must rely on their experience and knowledge when evaluating and using information, methods, -

27Th ANNUAL RESEARCH DAY & Henderson Lecture

27th ANNUAL RESEARCH DAY & Henderson Lecture FRIDAY, MAY 7, 2010 8:00 a.m. to 6:30 p.m. Northrop Frye Hall, Ground Floor Victoria University, 73 Queen's Park Crescent East University of Toronto M5S 1K7 Lecturer: Jane Norman MD Professor of Maternal and Fetal Health, University of Edinburgh, UK Co-Director, Edinburgh Tommy’s Centre for Maternal and Fetal Health Research Topic: Being Born Too Soon – Do Obstetricians Have Anything To Offer? Abstract deadline: Friday, March 5, 2010 http://www.obgyn.utoronto.ca/Research/ResearchDay.htm For additional information or assistance, please contact Helen Robson at [email protected] PROGRAMME-AT-A-GLANCE (A.M.) Department of Obstetrics & Gynaecology 27th Annual Research Day, Friday, May 7, 2010 Northrop Frye Hall, Victoria University, University of Toronto, 73 Queen’s Park Crescent NF=Northrop Frye Hall Burwash Hall is located at the north end of the Victoria Quad 7:30 a.m. on Poster Set-up for Poster Session I [NF, ground floor, Rms. 004, 006, 007 & 008] 8:00 a.m. Registration & Continental Breakfast [NF, ground floor lobby] 8:25 – 8:30 a.m. Welcome: Dr. Alan Bocking, Chair [NF, ground floor Lecture Hall, Rm. 003] 8:30 – 9:45 a.m. Oral Session I (O1-O5) [NF, ground floor Lecture Hall, Rm. 003] 9:45 – 10:05 a.m. Coffee Break & Poster Session I Walkabout [NF, ground floor lobby; Rms. 004, 006, 007 & 008] 10:05 – 11:05 a.m. Poster Session I Tour [NF, Rms. 004, 006, 007 & 008] Groups A-F Poster Takedown for a.m. -

Annualreport 2010

AnnualReport 2010 Seth G.S. Medical College & King Edward Memorial Hospital Municipal Corporation of Greater Mumbai Convocation Ceremony of Use of smart board by 1st MBBS students Fellowship and Certificate Courses Automated chappati maker Clean KEM campaign Cardiac Ambulance Seth G.S. Medical College & King Edward Memorial Hospital Municipal Corporation of Greater Mumbai ANNUAL REPORT 2010 Concept (Front & Back cover) Dr. Sanjay Oak Director -Medical Education and Major Hospitals Professor of Pediatric Surgery Publisher Diamond Jubilee Society Trust Seth G.S. Medical College & KEM Hospital, Parel, Mumbai 400 012. Printer Urvi Compugraphics A2/248, Shah & Nahar Industrial Estate, S.J. Marg, Lower Parel (West), Mumbai 400 013. Tel.: 91 - 22 - 2494 5863 © Seth GS Medical College & KEM Hospital, 2011 Acknowledgements Smt. Shraddha Jadhav Hon. Mayor Smt. Shailaja Girkar Shri Subodh Kumar Deputy Mayor Municipal Commissioner Shri Sunil Prabhu Smt. Manisha Patankar-Mhaiskar Leader of the House Additional Municipal Commissioner (Western Suburbs) Shri Rajhans Singh Shri Aseem Gupta Leader of the Opposition Additional Municipal Commissioner (Eastern Suburbs) Shri Rahul Shewale Shri Mohan Adtani Chairman-Standing Committee Additional Municipal Commissioner (City) Smt. Ashwini Mate Shri Rajeev Jalota Chairman-Public Health Committee Additional Municipal Commissioner (Projects) Shri Parshuram (Chotu) Desai Shri Rajendra Vale Chairman-Works Committee (City) Deputy Municipal Commissioner (Estate & General Administration) Shri Anil Pawar Shri Sanjay (Nana) Ambole Chairperson - Ward Committee Municipal Councillor From the Director’s desk..... The twin institutes of the Seth GS Medical College & KEM Hospital were established in 1926 with a nationalistic spirit to cater to the “health care needs of the northern parts of the island” to be manned entirely by Indians. -

Herbal Medicines in Pregnancy and Lactation : an Evidence-Based

00 Prelims 1410 10/25/05 2:13 PM Page i Herbal Medicines in Pregnancy and Lactation An Evidence-Based Approach Edward Mills DPh MSc (Oxon) Director, Division of Clinical Epidemiology Canadian College of Naturopathic Medicine North York, Ontario, Canada Jean-Jacques Duguoa MSc (cand.) ND Naturopathic Doctor Toronto Western Hospital Assistant Professor Division of Clinical Epidemiology Canadian College of Naturopathic Medicine North York, Ontario, Canada Dan Perri BScPharm MD MSc Clinical Pharmacology Fellow University of Toronto Toronto, Ontario, Canada Gideon Koren MD FACMT FRCP Director of Motherisk Professor of Medicine, Pediatrics and Pharmacology University of Toronto Toronto, Ontario, Canada With a contribution from Paul Richard Saunders PhD ND DHANP 00 Prelims 1410 10/25/05 2:13 PM Page ii © 2006 Taylor & Francis Medical, an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group First published in the United Kingdom in 2006 by Taylor & Francis Medical, an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN Tel.: ϩ44 (0)20 7017 6000 Fax.: ϩ44 (0)20 7017 6699 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.tandf.co.uk/medicine All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or trans- mitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1P 0LP. -

Journal of Threatened Taxa

PLATINUM The Journal of Threatened Taxa (JoTT) is dedicated to building evidence for conservaton globally by publishing peer-reviewed artcles OPEN ACCESS online every month at a reasonably rapid rate at www.threatenedtaxa.org. All artcles published in JoTT are registered under Creatve Commons Atributon 4.0 Internatonal License unless otherwise mentoned. JoTT allows unrestricted use, reproducton, and distributon of artcles in any medium by providing adequate credit to the author(s) and the source of publicaton. Journal of Threatened Taxa Building evidence for conservaton globally www.threatenedtaxa.org ISSN 0974-7907 (Online) | ISSN 0974-7893 (Print) Review Ramifications of reproductive diseases on the recovery of the Sumatran Rhinoceros Dicerorhinus sumatrensis (Mammalia: Perissodactyla: Rhinocerotidae) Nan E. Schafer, Muhammad Agil & Zainal Z. Zainuddin 26 February 2020 | Vol. 12 | No. 3 | Pages: 15279–15288 DOI: 10.11609/jot.5390.12.3.15279-15288 For Focus, Scope, Aims, Policies, and Guidelines visit htps://threatenedtaxa.org/index.php/JoTT/about/editorialPolicies#custom-0 For Artcle Submission Guidelines, visit htps://threatenedtaxa.org/index.php/JoTT/about/submissions#onlineSubmissions For Policies against Scientfc Misconduct, visit htps://threatenedtaxa.org/index.php/JoTT/about/editorialPolicies#custom-2 For reprints, contact <[email protected]> The opinions expressed by the authors do not refect the views of the Journal of Threatened Taxa, Wildlife Informaton Liaison Development Society, Zoo Outreach Organizaton, or any of -

Sperm Aneuploidy and DNA Fragmentation in Unexplained

Esquerré-Lamare et al. Basic and Clinical Andrology (2018) 28:4 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12610-018-0070-6 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Sperm aneuploidy and DNA fragmentation in unexplained recurrent pregnancy loss: a multicenter case-control study Camille Esquerré-Lamare1,2, Marie Walschaerts1,2, Lucie Chansel Debordeaux3, Jessika Moreau1,2, Florence Bretelle4, François Isus1,5, Gilles Karsenty6, Laetitia Monteil7, Jeanne Perrin8,9, Aline Papaxanthos-Roche3 and Louis Bujan1,2* Abstract Background: Recurrent pregnancy loss (RPL) is defined as the loss of at least three pregnancies in the first trimester. Although the most common cause is embryo aneuploidy, and despite female checkup and couple karyotyping, in about 50% of cases RPL remain unexplained. Male implication has little been investigated and results are discordant. In this context, we conducted a multi-center prospective case-control study to investigate male gamete implication in unexplained RPL. Methods: A total of 33 cases and 27 controls were included from three university hospitals. We investigated environmental and family factors with a detailed questionnaire and andrological examination, sperm characteristics, sperm DNA/chromatin status using the sperm chromatin structure assay (SCSA) and terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) and sperm aneuploidy using fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH). The Mann-Whitney test and the Wilcoxon or Fisher exact tests were used. A non-parametric Spearman correlation was performed in order to analyze the relationship between various sperm parameters and FISH and sperm DNA fragmentation results. Results: We found significant differences between cases and controls in time to conceive, body mass index (BMI), family history of infertility and living environment. -

International Publications (2009)

INTERNATIONAL PUBLICATIONS Faculty of Medicine, Cairo University (2009) Edited by: Professor Dr. Lamis Ragab Professor Dr. Taymour Mostafa Professor Dr. Hesham El Anany Professor Dr. Rania Mohamed Printed by MEDC INDEX 1 Pubmed Index Publications …………………………. 1-157 2 Other Cited Publications ……………………………. 158-163 3 a. Oral Presentations at International Conferences … 164-169 b. Poster Presentations at International Conferences . 170-173 c. Abstracts in International Conferences ………….. 174-176 An important part of the mission of Kasr Al Aini Faculty of Medicine, Cairo University is training a professional, specialized graduate able to conduct research and apply national and international standards of medical care. The institution should prove that academic research activities make a full contribution to the achievement of the mission. The quality and quantity of research activities should be documented. This is the third document of the published research of the faculty in international journals. The number of staff involved in peer reviewed published research is 415. We aim to increase this record by encouraging staff, especially the young generations, to publish their research in international journals with a high impact factor. The quality and quantity of research activities is an important factor in accrediting academic instutitions and ranking of universities. Dean of the Faculty Vice Dean for Postgraduate Studies & Research Prof. Dr. Ahmed Sameh Farid Prof. Dr. Lamis Ragab International Publications Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2009 Feb;53(2):251-6. Impact Factor: 1.953 Effect of dexmedetomidine on the characteristics of bupivacaine in a caudal block in pediatrics. Saadawy I, Boker A, Elshahawy MA, Almazrooa A, Melibary S, Abdellatif AA, Afifi W. -

Accepted Manuscript

ACCEPTED MANUSCRIPT Prenatal inflammation exposure-programmed cardiovascular diseases and potential prevention Youcai Denga,b,1,*, Liang Songa,b,1, Xuqiang Niea,b, Weinian Shoua,b,c, Xiaohui Lia,b,* aInstitute of Materia Medica, College of Pharmacy, Army Medical University (Third Military Medical University), 30# Gaotanyan Rd., Shapingba District, Chongqing 400038, China bCenter of Translational Medicine, College of Pharmacy, Army Medical University (Third Military Medical University), 30# Gaotanyan Rd., Shapingba District, Chongqing 400038, China cHerman B Wells Center for Pediatric Research, Department of Pediatrics, Indiana University School of Medicine, 1044 W. Walnut Street, R4 W302D, Indianapolis, IN 46202, USA 1These authors equally contributed to this work. *Address correspondence to: Xiaohui Li and Youcai Deng Address: Room 606, Pharmaceutical Sciences Building, 30# Gaotanyan Rd, Shapingba District, Chongqing 400038, China Tel.: (86) 23-68771632;ACCEPTED MANUSCRIPT Fax: (86)23-68753397 Email address: [email protected] (Y. Deng); [email protected] (X. Li) ___________________________________________________________________ This is the author's manuscript of the article published in final edited form as: Deng, Y., Song, L., Nie, X., Shou, W., & Li, X. (n.d.). Prenatal inflammation exposure-programmed cardiovascular diseases and potential prevention. Pharmacology & Therapeutics. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pharmthera.2018.05.009 ACCEPTED MANUSCRIPT Abstract In recent years, the rapid development of medical and pharmacological interventions has led to a steady decline in certain noncommunicable chronic diseases (NCDs), such as cancer. However, the overall incidence of cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) has not seemed to decline. CVDs have become even more prevalent in many countries and represent a global health threat and financial burden. -

Job Analysis Final Report for Web2

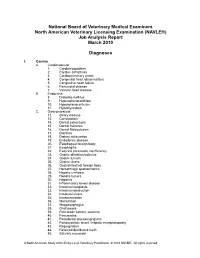

National Board of Veterinary Medical Examiners North American Veterinary Licensing Examination (NAVLE®) Job Analysis Report March 2010 Diagnoses I. Canine A. Cardiovascular 1. Cardiomyopathies 2. Cardiac arrhythmia 3. Cardiopulmonary arrest 4. Congenital heart abnormalities 5. Congestive heart failure 6. Pericardial disease 7. Valvular heart disease B. Endocrine 8. Diabetes mellitus 9. Hyperadrenocorticism 10. Hypoadrenocorticism 11. Hypothyroidism C. Gastrointestinal 12. Biliary disease 13. Constipation 14. Dental extractions 15. Dental fractures 16. Dental Malocclusion 17. Diarrhea 18. Dietary indiscretion 19. Endodontic disease 20. Esophageal foreign body 21. Esophagitis 22. Exocrine pancreatic insufficiency 23. Gastric dilatation/volvulus 24. Gastric tumors 25. Gastric ulcers 26. Gastrointestinal foreign body 27. Hemorrhagic gastroenteritis 28. Hepatic cirrhosis 29. Hepatic tumors 30. Hepatitis 31. Inflammatory bowel disease 32. Intestinal neoplasia 33. Intestinal obstruction 34. Intestinal ulcers 35. Intussusception 36. Malnutrition 37. Megaesophagus 38. Oral tumors 39. Pancreatic tumors, exocrine 40. Pancreatitis 41. Periodontal disease/gingivitis 42. Portosystemic shunt / hepatic encephalopathy 43. Regurgitation 44. Retained deciduous teeth 45. Salivary mucocele A North American Study of the Entry-Level Veterinary Practitioner © 2010 NBVME. All rights reserved. D. Hemic/Lymphatic 46. Anemia (general) 47. Immune mediated hemolytic anemia 48. Immune mediated thrombocytopenia 49. Canine juvenile cellulitis 50. Coagulopathy 51. Hemangiosarcoma 52. Immunodeficiency 53. Lymphadenopathy 54. Lymphosarcoma / leukemia 55. Mast cell tumor 56. Systemic lupus erythematosus 57. Transfusion therapy E. Integumentary 58. Abscesses 59. Acral lick granuloma 60. Allergic dermatitis 61. Alopecia 62. Anal sac disease 63. Aural hematoma 64. Bite wounds 65. Burns 66. Decubitus ulcers 67. Dermatophytosis 68. Diseases of claws 69. Diseases of pads 70. Otitis externa/media 71. -

NAD Deficiency Due to Environmental Factors Or Gene–Environment Interactions Causes Congenital Malformations and Miscarriage in Mice

NAD deficiency due to environmental factors or gene–environment interactions causes congenital malformations and miscarriage in mice Hartmut Cunya,b, Melissa Rapadasa,1, Jessica Gereisa,1, Ella M. M. A. Martina, Rosemary B. Kirka, Hongjun Shia,2, and Sally L. Dunwoodiea,b,c,3 aDevelopmental and Stem Cell Biology Division, Victor Chang Cardiac Research Institute, Sydney, NSW 2010, Australia; bFaculty of Medicine, University of New South Wales, Sydney, NSW 2052, Australia; and cFaculty of Science, University of New South Wales, Sydney, NSW 2052, Australia Edited by Nancy C. Andrews, Duke University School of Medicine, Durham, NC, and approved January 3, 2020 (received for review September 26, 2019) Causes for miscarriages and congenital malformations can be central concept of pharmacogenetics, which studies the effects of genetic, environmental, or a combination of both. Genetic variants, genetic heterogeneity on drug response (6). Similarly, diet is an hypoxia, malnutrition, or other factors individually may not affect environmental factor that has been implicated in gene–environment embryo development, however, they may do so collectively. Biallelic interactions and congenital malformations (7). The composition of loss-of-function variants in HAAO or KYNU, two genes of the nico- the maternal diet has, for example, been linked to the causation of tinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD) synthesis pathway, are caus- neural tube defects. In 1991, a randomized double-blind trial ative of congenital malformation and miscarriage in humans and revealed that these defects are primarily a vitamin deficiency dis- mice. The variants affect normal embryonic development by disrupt- order, which can be prevented in 80% of cases by daily dietary ing the synthesis of NAD, a key factor in multiple biological pro- supplementation with folic acid before and during the first tri- cesses, from its dietary precursor tryptophan, resulting in NAD mester of pregnancy (8). -

9828 MA Preg Loss 24/04/2013 11:43 Page 17

33456_WhyMe_3425_DM:9828 MA preg loss 24/04/2013 11:43 Page 17 Why me? 33456_WhyMe_3425_DM:9828 MA preg loss 24/04/2013 11:43 Page 2 Miscarriages happen for lots of different reasons. Sometimes the cause is known but often it isn’t. Some women benefit from treatment but others don’t need it. This leaflet looks at the possible causes of miscarriage and the tests and treatment that might help you. What is a miscarriage? What happens now? Miscarriage is when you lose your If this is your first or second baby any time up to 24 weeks of miscarriage, you probably won’t be pregnancy. After 24 weeks losing a offered tests or treatment. That’s baby during pregnancy or labour is because most women go on to have a called a stillbirth. successful pregnancy next time. Miscarriage is very common. No one But if you think there is a good reason knows exactly how many miscarriages for having tests now, perhaps because happen, but experts think that more of your age or the time it took you to than one pregnancy in every five ends conceive, you might want to talk to in miscarriage. your GP about an earlier referral. There is still a lot that we don’t know If you’ve had three miscarriages or about miscarriage, and you may never more in a row, you should be offered find out why it happened to you. That tests. That’s because a cause is more can be hard to cope with. likely to be found at this stage. -

SLE and Pregnancy

21 SLE and Pregnancy Hanan Al-Osaimi and Suvarnaraju Yelamanchili King Fahad Armed Forces Hospital, Jeddah Saudi Arabia 1. Introduction Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is an autoimmune disease that affects multiple organs. Disease flares can occur at any time during pregnancy and postpartum without any clear pattern. The hormonal and physiological changes that occur in pregnancy can induce lupus activity. Likewise the increased inflammatory response during a lupus flare can cause significant complications in pregnancy. Distinguishing between signs of lupus activity and pregnancy either physiological or pathological can be difficult [Clowse, 2007]. Pregnancy is a crucial issue that needs to be clearly discussed in details in all female patients with SLE who are in the reproductive age group. There are two essential concerns. The first one is the Lupus activity on pregnancy and the second one is the influence of pregnancy on Lupus. That is the reason why pregnancy should be planned at least six months of remission with close follow-up for SLE flares. Women with SLE usually have complicated pregnancies out of which one third will result in cesarean section, one third will have preterm delivery and more than 20% will be complicated by preeclampsia [Clowse, 2006; Clark, 2003]. Rarely an SLE patient with a controlled disease activity may deteriorate as pregnancy advances, but still the pregnancy outcome can be better if pregnancy is well timed and managed. 2. Physiology of pregnancy There are increased demands by the mother, fetus and the placenta during pregnancy which is to be met by the mother’s organ systems. Therefore there are some cardiovascular, hematological, immunological, endocrinal and metabolic changes in the mother in normal pregnancy.