Summer 2019 CONTENTS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Union Election Held Amidst Charges of Improprieties Bulls Saga Continues

Holy Terrors: Duke Athletics beat a bunch of religious fanatics in straight sets 6-1,6-1, 6-0. Chris THE CHRONICLE Yankee scored a hat trick in the hat trick. THURSDAY. SEPTEMBER 27. 1990 DUKE UNIVERSITY DURHAM, NORTH CAROLINA CIRCULATION: 15.000 VOL. 86. NO. 25 Union election held amidst charges of improprieties By ADRIAN DOLLARD by ineligible people, do not occur. Today's union election is being Scott asked the administration held despite charges of improper to allow two Bryan Center house conduct. keepers, Louis Owens and Members of the union repre Frederick Ferrell, time off from senting most housekeeping and work to serve as poll watchers. Food Services workers claim Her request was denied. The following are polling times and places for the Local 77 union officers and University ad Observers were selected from election. Employees can vote at any station regardless of where ministrators unfairly aided in the list provided by the Local's they work. cumbent candidates. Business Manager Jimmy Pugh instead. Scott claims the Univer The union, Local 77 of the LOCATION TIME American Federation of State, sity thereby violated federal law County and Municipal Employ by "improperly favoring the in West Union, basement lounge 6:30 a.m.-4:30 p.m cumbents over the other candi ees, represents 500 University Hospital North, Room 1103 6:30 a.m.-9 a.m. employees. dates." "There is no way that a fair In addition, she alleges the ad Hospital North, Room 1109 3:30 p.m.-5 p.m. ministration violated laws bar election can be held" under pres Hospital South, 6:30 a.m.-9 a.m. -

Grunge Is Dead Is an Oral History in the Tradition of Please Kill Me, the Seminal History of Punk

THE ORAL SEATTLE ROCK MUSIC HISTORY OF GREG PRATO WEAVING TOGETHER THE DEFINITIVE STORY OF THE SEATTLE MUSIC SCENE IN THE WORDS OF THE PEOPLE WHO WERE THERE, GRUNGE IS DEAD IS AN ORAL HISTORY IN THE TRADITION OF PLEASE KILL ME, THE SEMINAL HISTORY OF PUNK. WITH THE INSIGHT OF MORE THAN 130 OF GRUNGE’S BIGGEST NAMES, GREG PRATO PRESENTS THE ULTIMATE INSIDER’S GUIDE TO A SOUND THAT CHANGED MUSIC FOREVER. THE GRUNGE MOVEMENT MAY HAVE THRIVED FOR ONLY A FEW YEARS, BUT IT SPAWNED SOME OF THE GREATEST ROCK BANDS OF ALL TIME: PEARL JAM, NIRVANA, ALICE IN CHAINS, AND SOUNDGARDEN. GRUNGE IS DEAD FEATURES THE FIRST-EVER INTERVIEW IN WHICH PEARL JAM’S EDDIE VEDDER WAS WILLING TO DISCUSS THE GROUP’S HISTORY IN GREAT DETAIL; ALICE IN CHAINS’ BAND MEMBERS AND LAYNE STALEY’S MOM ON STALEY’S DRUG ADDICTION AND DEATH; INSIGHTS INTO THE RIOT GRRRL MOVEMENT AND OFT-OVERLOOKED BUT HIGHLY INFLUENTIAL SEATTLE BANDS LIKE MOTHER LOVE BONE, THE MELVINS, SCREAMING TREES, AND MUDHONEY; AND MUCH MORE. GRUNGE IS DEAD DIGS DEEP, STARTING IN THE EARLY ’60S, TO EXPLAIN THE CHAIN OF EVENTS THAT GAVE WAY TO THE MUSIC. THE END RESULT IS A BOOK THAT INCLUDES A WEALTH OF PREVIOUSLY UNTOLD STORIES AND FRESH INSIGHT FOR THE LONGTIME FAN, AS WELL AS THE ESSENTIALS AND HIGHLIGHTS FOR THE NEWCOMER — THE WHOLE UNCENSORED TRUTH — IN ONE COMPREHENSIVE VOLUME. GREG PRATO IS A LONG ISLAND, NEW YORK-BASED WRITER, WHO REGULARLY WRITES FOR ALL MUSIC GUIDE, BILLBOARD.COM, ROLLING STONE.COM, RECORD COLLECTOR MAGAZINE, AND CLASSIC ROCK MAGAZINE. -

Holy Name of Jesus Church

Holy Name of Jesus Church Pastoral Assistant for Liturgy & Music: Rev. Albert Pinciaro, Pastor Sue Scanlon Rev. Msgr. J. James Cuneo, J.C.D., Choir Director/Cantor: Nina DeMasi Pastoral Associate Emeritus Parish Secretary, Faith Formation Facilitator: Rev. Churchill Penn, In Residence Maryjean daSilva Deacon Dan O’Connor Finance Board Chair: Anne Wargo Parish Trustees: Carol Bogue & Greg Moreau MASSES: MARRIAGE Saturday Vigil: 4:30 p.m. We celebrate Christian love and family with the Sacrament NEW SUNDAY SCHEDULE: 8:15 A.M. & 10:45 A.M. of Matrimony. Couples should contact the office one year in Daily: Monday - Friday - 7:30 a.m. advance. Marian Devotions follow Monday morning Mass. ANOINTING OF THE SICK Adoration following Wednesday morning Mass Anyone who is ill and in need of prayers, comfort and/or NEW PARISHIONERS strength should call the office to arrange to receive this beautiful Sacrament. Please call, visit the office or register online. SACRAMENTAL EVENTS: BAPTISM HOSPITALIZATION We celebrate new Christian life with Holy Baptism. Families If you or a loved one is hospitalized or homebound, please are requested to contact the office before the arrival of your notify us to receive care. We are not notified due to new child for instructions and registration. HIPAA law. RECONCILIATION BULLETIN SUBMISSIONS Saturdays from 3:00-3:45p.m. and weekdays by request. Please submit to: [email protected] 5TH SUNDAY OF LENT MARCH 29, 2020 WHAT’S HAPPENING THI S W E E K Mon 3/30 Tues 3/31 Wed April 1 Thur 4/2 Fri 4/3 Sat 4/4 Sun 4/5 7:30 am Mass 7:30 am Mass 7:30 am Mass 7:30 am Mass 7:30 am Mass 4:30 pm Mass 8:15 am Mass +Antonio +Sylvain Family +Sr. -

Hiroshima, Nagasaki, and Minamata 1945 to 1975

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by The University of Utah: J. Willard Marriott Digital Library THE EXPERIENCE OF THE EXCLUDED: HIROSHIMA, NAGASAKI, AND MINAMATA 1945 TO 1975 by Robert C. Goodwin A thesis submitted to the faculty of The University of Utah in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Asian Studies College of the Humanities The University of Utah August 2010 Copyright © Robert C. Goodwin 2010 All Rights Reserved T h e U n i v e r s i t y o f U t a h G r a d u a t e S c h o o l STATEMENT OF THESIS APPROVAL The thesis of Robert C. Goodwin has been approved by the following supervisory committee members: Wesley M. Sasaki-Uemura , Chair June 3, 2010 Date Approved Janet M. Theiss , Member June 3, 2010 Date Approved Mamiko C. Suzuki , Member June 3, 2010 Date Approved and by Janet M. Theiss , Chair of the Department of Asian Studies Program and by Charles A. Wight, Dean of the Graduate School. ABSTRACT After Japan’s defeat in the Pacific War in 1945, the country became not only ground zero for the first use of atomic weapons, but also experienced year zero of the postwar, democratic era—the top-down reorganization of the country politically and socially—ushered in by the American Occupation. While the method of government changed, the state rallied around two pillars: the familiar fixture of big business and economics, and the notion of “peace” supplied by the new constitution. -

Total Tracks Number: 1108 Total Tracks Length: 76:17:23 Total Tracks Size: 6.7 GB

Total tracks number: 1108 Total tracks length: 76:17:23 Total tracks size: 6.7 GB # Artist Title Length 01 00:00 02 2 Skinnee J's Riot Nrrrd 03:57 03 311 All Mixed Up 03:00 04 311 Amber 03:28 05 311 Beautiful Disaster 04:01 06 311 Come Original 03:42 07 311 Do You Right 04:17 08 311 Don't Stay Home 02:43 09 311 Down 02:52 10 311 Flowing 03:13 11 311 Transistor 03:02 12 311 You Wouldnt Believe 03:40 13 A New Found Glory Hit Or Miss 03:24 14 A Perfect Circle 3 Libras 03:35 15 A Perfect Circle Judith 04:03 16 A Perfect Circle The Hollow 02:55 17 AC/DC Back In Black 04:15 18 AC/DC What Do You Do for Money Honey 03:35 19 Acdc Back In Black 04:14 20 Acdc Highway To Hell 03:27 21 Acdc You Shook Me All Night Long 03:31 22 Adema Giving In 04:34 23 Adema The Way You Like It 03:39 24 Aerosmith Cryin' 05:08 25 Aerosmith Sweet Emotion 05:08 26 Aerosmith Walk This Way 03:39 27 Afi Days Of The Phoenix 03:27 28 Afroman Because I Got High 05:10 29 Alanis Morissette Ironic 03:49 30 Alanis Morissette You Learn 03:55 31 Alanis Morissette You Oughta Know 04:09 32 Alaniss Morrisete Hand In My Pocket 03:41 33 Alice Cooper School's Out 03:30 34 Alice In Chains Again 04:04 35 Alice In Chains Angry Chair 04:47 36 Alice In Chains Don't Follow 04:21 37 Alice In Chains Down In A Hole 05:37 38 Alice In Chains Got Me Wrong 04:11 39 Alice In Chains Grind 04:44 40 Alice In Chains Heaven Beside You 05:27 41 Alice In Chains I Stay Away 04:14 42 Alice In Chains Man In The Box 04:46 43 Alice In Chains No Excuses 04:15 44 Alice In Chains Nutshell 04:19 45 Alice In Chains Over Now 07:03 46 Alice In Chains Rooster 06:15 47 Alice In Chains Sea Of Sorrow 05:49 48 Alice In Chains Them Bones 02:29 49 Alice in Chains Would? 03:28 50 Alice In Chains Would 03:26 51 Alien Ant Farm Movies 03:15 52 Alien Ant Farm Smooth Criminal 03:41 53 American Hifi Flavor Of The Week 03:12 54 Andrew W.K. -

To the MSU Bookstore!

2 THURSDAY. DECEMBER 9, 2004 NEWS Beware of Peg-Leg Pirates ~ OMER GOMER much less one that happens on shoots. out, f~ying anything in its his flesh path, 111clud111g oak trees, small E XCREMENT W RITER . ·1d · T.k. 1 k If the pirate does this, he will chi ren, puppies, 1 ·1 c oc ·s, In the ramblings and run-on probably be off-balance, unle s and hedgehogs, unless they are sentences I'm writing today I plan he has managed to fuse some sort named Sonic, because then the) to warn everyone about the Yery of tail or other balancing device would be able to outrun any kind real threat of pirates. Why you to hi~ body in his secret pirate of laser beam while grabbing ask? Because if I don't, who will? lair. However, since most pirates assorted gold rings for no appar Pirates come in all shapes are poor, they would not be able ent purpose. and sizes. Some are short and fat, to .ifford to do thi , which is an !f ever trapped in this situ while others are tall and skinny. advanrage to anyone caught in the ation, hold a mirror up to the However, all are dangerous. midst of person-to-pirate com- pirate. Pirates are very vain .ind Pirates don't care who you bat. When thev are getting ready stupid creatures. They will be fas are or where you're from. In fact, to launch their peg leg of death cinated by their own appearance, _... illustration by Paya Sharna they're probably just wondering at your face, one must simply but unfortunately will not realize Eyepatches and parrots are dead gJve-aways when identifjing pi7' how the hell they managed to push the pirates over. -

Thomas Phleps

9/11 UND DIE FOLGEN IN DER POPMUSIK I. TON-SPUREN Thomas Phleps 1. REMIXES Eine der ersten musikbezogenen Reaktionen nach 9/11 war die Produktion von Remixes, die in diesem Falle nicht Musik vermischten, sondern Musik und O-Töne der Berichterstattung am Tage der Anschläge. Im deutschspra- chigen Raum hatte die SynthPop-Band And One ihr Doku-Remix »Amerika brennt« am 15. September als »aktuelles Zeitdokument« und »um unsere Wut zu verewigen« ins Netz gestellt: eine hart an der Peinlichkeitsgrenze angesiedelte Collage aus Nachrichtensplittern, Augenzeugenberichten, George W. Bush-Worten, Sinatras »New York, New York«, wabernden Sphären-Keyboards und zackigen Beats — laut Selbstaussage »für all die [...], die ihren Weg der Verzweiflung mit uns gehen wollen und die Tanz- fläche als ein Medium der Hoffnung verstehen« (http://www.andone.com). In den USA wurden Doku-Remixes vor allem von den Radio- und Fernseh- stationen (hier noch gekoppelt mit den allbekannten Bildern — vorgeblich der Trauer und Hoffnung) produziert. Innerhalb kürzester Zeit schwirrten an die 100 dieser Remixes durch den Äther, darunter mehrere Bearbeitungen von John Lennons »Imagine«, einem Song, der nach 9/11 zunächst auf der Clear Channel-Liste fragwürdiger Tex- te (s.u.) auftauchte (und außerdem am 21. September 2001 beim größten Auflauf populärer Künstler, dem in New York und Los Angeles parallel veran- stalteten und von über 8000 Fernseh- und Radiostationen live übertragenen Benefizkonzert A Tribute To Heroes, überraschenderweise von Neil Young interpretiert wurde — dem Manne also, der wenig später mit seinem kriege- rischen »Let's Roll« höchstpersönlich die letzten Insignien einer pazifistisch- gewaltfreien Popmusik aus dem Wege räumte). Eines der vielen »Imagine«-Remixes zeigt an, dass hier vielfach mit heißer Nadel gestrickt wurde bzw. -

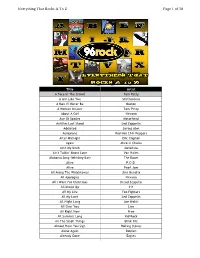

Of 30 Everything That Rocks a to Z

Everything That Rocks A To Z Page 1 of 30 Title Artist A Face In The Crowd Tom Petty A Girl Like You Smithereens A Man I'll Never Be Boston A Woman In Love Tom Petty About A Girl Nirvana Ace Of Spades Motorhead Achilles Last Stand Led Zeppelin Addicted Saving Abel Aeroplane Red Hot Chili Peppers After Midnight Eric Clapton Again Alice In Chains Ain't My Bitch Metallica Ain't Talkin' About Love Van Halen Alabama Song (Whiskey Bar) The Doors Alive P.O.D. Alive Pearl Jam All Along The Watchtower Jimi Hendrix All Apologies Nirvana All I Want For Christmas Dread Zeppelin All Mixed Up 311 All My Life Foo Fighters All My Love Led Zeppelin All Night Long Joe Walsh All Over You Live All Right Now Free All Summer Long Kid Rock All The Small Things Blink 182 Almost Hear You Sigh Rolling Stones Alone Again Dokken Already Gone Eagles Everything That Rocks A To Z Page 2 of 30 Always Saliva American Bad Ass Kid Rock American Girl Tom Petty American Idiot Green Day American Woman Lenny Kravitz Amsterdam Van Halen And Fools Shine On Brother Cane And Justice For All Metallica And The Cradle Will Rock Van Halen Angel Aerosmith Angel Of Harlem U2 Angie Rolling Stones Angry Chair Alice In Chains Animal Def Leppard Animal Pearl Jam Animal I Have Become Three Days Grace Animals Nickelback Another Brick In The Wall Pt. 2 Pink Floyd Another One Bites The Dust Queen Another Tricky Day The Who Anything Goes AC/DC Aqualung Jethro Tull Are You Experienced? Jimi Hendrix Are You Gonna Be My Girl Jet Are You Gonna Go My Way Lenny Kravitz Armageddon It Def Leppard Around -

Seas of Sorrow, Lakes of Heaven: Community and Ishimure Michiko

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses Dissertations and Theses July 2020 Seas of Sorrow, Lakes of Heaven: Community and Ishimure Michiko Brett Kaufman University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/masters_theses_2 Part of the Japanese Studies Commons Recommended Citation Kaufman, Brett, "Seas of Sorrow, Lakes of Heaven: Community and Ishimure Michiko" (2020). Masters Theses. 928. https://doi.org/10.7275/17621364 https://scholarworks.umass.edu/masters_theses_2/928 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations and Theses at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SEAS OF SORROW, LAKES OF HEAVEN: COMMUNITY AND ISHIMURE MICHIKO A Thesis Presented by BRETT KAUFMAN Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment Of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts May 2020 Japanese East Asian Language and Cultures SEAS OF SORROW, LAKES OF HEAVEN: COMMUNITY AND ISHIMURE MICHIKO A Thesis Presented By BRETT KAUFMAN Approved as to style and content by: ___________________________________________ Amanda Seaman, Chair ___________________________________________ Stephen Miller, Member ________________________________________ Bruce Baird, Unit Director East Asian Languages and Cultures Program Department of Languages, Literatures and Cultures ________________________________________ Robert G. Sullivan, Chair Department of Languages, Literatures and Cultures DEDICATION For Sammy ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I’d like to take the opportunity to thank all of my professors who helped me over the course of this program. To my chair, I would like to thank Professor Amanda Seaman for all of the advice and help that allowed me to complete this project. -

Alice in Chains Facelift Mp3, Flac, Wma

Alice In Chains Facelift mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: Facelift Country: Europe Released: 1990 Style: Alternative Rock, Grunge MP3 version RAR size: 1447 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1283 mb WMA version RAR size: 1807 mb Rating: 4.7 Votes: 125 Other Formats: WMA FLAC MIDI AIFF AC3 AUD FLAC Tracklist Hide Credits A1 We Die Young 2:32 A2 Man In The Box 4:46 A3 Sea Of Sorrow 5:49 A4 Bleed The Freak 4:01 A5 I Can't Remember 3:42 A6 Love, Hate, Love 6:27 B1 It Ain't Like That 4:37 B2 Sunshine 4:44 B3 Put You Down 3:16 Confusion B4 5:44 Backing Vocals – Michael Starr B5 I Know Somethin (Bout You) 4:21 B6 Real Thing 4:03 Companies, etc. Distributed By – CBS Records Phonographic Copyright (p) – CBS Records Inc. Copyright (c) – CBS Records Inc. Recorded At – London Bridge Studio Recorded At – Capitol Studios Mixed At – Soundcastle Mastered At – Future Disc Manufactured By – Sony/CBS, Haarlem Credits A&R – Nick Terzo Art Direction – David Coleman Bass – Michael Starr Booking [Agency] – ICM , Jeff Rowland Design [Logo] – David Coleman Drums, Percussion – Sean Kinney Engineer [Additional] – Ron Champagne Engineer [Assistant Mix] – Bob Lacivita Engineer [Assistant] – Leslie Ann Jones Guitar, Backing Vocals – Jerry Cantrell Management – Kelly Curtis, Susan Silver Mastered By – Eddy Schreyer Photography By – Rocky Schenck Product Manager – Peter Fletcher Recorded By, Producer, Mixed By – Dave Jerden Vocals – Layne Staley Notes The release comes with a black and white printed inner sleeve featuring lyrics and publishing details. -

Minamata Disease and the Miracle of the Human Desire to Live

Volume 6 | Issue 4 | Article ID 2732 | Apr 01, 2008 The Asia-Pacific Journal | Japan Focus Reborn from the Earth Scarred by Modernity: Minamata Disease and the Miracle of the Human Desire to Live Ishimure Michiko Reborn from the Earth Scarred byher non-fiction prose, Ishimure’s poetry and Modernity: Minamata Disease and the fiction have also won acclaim, including her Miracle of the Human Desire to Live 1997 novel, Tenko (forthcoming in English translation by Bruce Allen as Lake of Heaven). Ishimure Michiko MB Translated by Michael Bourdaghs The mouth of the Minamata River flows down For nearly half a century, Ishimure Michiko (b. into the Shiranui Sea. We called the strand that 1927) has been an important voice in Japanese stretches out broadly to the leftUmawari no environmental literature. She first came to Tomo. national attention as a result of her writings on the ongoing environmental disaster ofSome two hundred years ago, it was apparently Minamata Disease. Caused by the methyl a shallow, gently sloping beach. Small mercury and other poisonous industrial wastes fishermen’s homes dotted the shoreline. dumped by the Chisso Corporation into the harbor at the town of Minamata, theThis embankment that sits between the town debilitating neurological syndrome first began inland and the Chisso chemical plant built on appearing in the mid 1950s, but wonits outskirts was originally formed by the plants widespread attention only in the 1960s, thanks that flourished naturally there—susuki grass, to the efforts of local residents and activists. yoshitake reeds, wild chrysanthemums with Ishimure’s 1969 bookKugai jÅdo: Waga their tiny flowers, oleaster trees. -

Alice in Chains Facelift Mp3, Flac, Wma

Alice In Chains Facelift mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: Facelift Country: Poland Released: 1993 Style: Alternative Rock, Grunge MP3 version RAR size: 1204 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1400 mb WMA version RAR size: 1226 mb Rating: 4.1 Votes: 287 Other Formats: DXD AA VOX MP1 VQF WMA AAC Tracklist Hide Credits We Die Young 1 2:32 Music By, Lyrics By – Cantrell* Man In The Box 2 4:46 Lyrics By – Staley*Music By – Cantrell* Sea Of Sorrow 3 5:49 Music By, Lyrics By – Cantrell* Bleed The Freak 4 4:01 Music By, Lyrics By – Cantrell* I Can't Remember 5 3:42 Lyrics By – Staley*Music By, Lyrics By – Cantrell* Love, Hate, Love 6 6:27 Lyrics By – Staley*Music By – Cantrell* It Ain't Like That 7 4:37 Lyrics By – Cantrell*Music By – Cantrell*, Starr*, Kinney* Sunshine 8 4:44 Music By, Lyrics By – Cantrell* Put You Down 9 3:16 Music By, Lyrics By – Cantrell* Confusion 10 5:44 Backing Vocals – Michael StarrLyrics By – Staley*Music By – Cantrell*, Starr* I Know Somethin (Bout You) 11 4:21 Music By, Lyrics By – Cantrell* Real Thing 12 4:03 Lyrics By – Staley*Music By – Cantrell* Companies, etc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – Sony Music Entertainment Inc. Copyright (c) – Sony Music Entertainment Inc. Distributed By – Sony Music Manufactured By – Sony Music – S4246720110-0101 Made By – Sony Music Entertainment Inc. Published By – Buttnugget Publishing Published By – Jack Lord Music Published By – Phlembot Music Published By – Lungclam Music Recorded At – London Bridge Studio Recorded At – Capitol Studios Mixed At – Soundcastle Mastered