Opportunities and Challenges of Using Systematic Reviews to Summarize

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Opportunities for Selective Reporting of Harms in Randomized Clinical Trials: Selection Criteria for Nonsystematic Adverse Events

Opportunities for selective reporting of harms in randomized clinical trials: Selection criteria for nonsystematic adverse events Evan Mayo-Wilson ( [email protected] ) Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg School of Public Health https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6126-2459 Nicole Fusco Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg School of Public Health Hwanhee Hong Duke University Tianjing Li Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg School of Public Health Joseph K. Canner Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine Kay Dickersin Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg School of Public Health Research Article Keywords: Harms, adverse events, clinical trials, reporting bias, selective outcome reporting, data sharing, trial registration Posted Date: February 5th, 2019 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.2.268/v1 License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Read Full License Version of Record: A version of this preprint was published on September 5th, 2019. See the published version at https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-019-3581-3. Page 1/16 Abstract Background: Adverse events (AEs) in randomized clinical trials may be reported in multiple sources. Different methods for reporting adverse events across trials, or across sources for a single trial, may produce inconsistent and confusing information about the adverse events associated with interventions Methods: We sought to compare the methods authors use to decide which AEs to include in a particular source (i.e., “selection criteria”) and to determine how selection criteria could impact the AEs reported. We compared sources (e.g., journal articles, clinical study reports [CSRs]) of trials for two drug-indications: gabapentin for neuropathic pain and quetiapine for bipolar depression. -

Systematic Reviews in Health Care: Meta-Analysis in Context

© BMJ Publishing Group 2001 Chapter 4 © Crown copyright 2000 Chapter 24 © Crown copyright 1995, 2000 Chapters 25 and 26 © The Cochrane Collaboration 2000 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopy- ing, recording and/or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publishers. First published in 1995 by the BMJ Publishing Group, BMA House, Tavistock Square, London WC1H 9JR www.bmjbooks.com First edition 1995 Second impression 1997 Second edition 2001 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 0-7279-1488–X Typeset by Phoenix Photosetting, Chatham, Kent Printed and bound by MPG Books, Bodmin, Cornwall Contents Contributors viii Foreword xiii Introduction 1 Rationale, potentials, and promise of systematic reviews 3 MATTHIAS EGGER, GEORGE DAVEY SMITH, KEITH O’ROURKE Part I: Systematic reviews of controlled trials 2 Principles of and procedures for systematic reviews 23 MATTHIAS EGGER, GEORGE DAVEY SMITH 3 Problems and limitations in conducting systematic reviews 43 MATTHIAS EGGER, KAY DICKERSIN, GEORGE DAVEY SMITH 4 Identifying randomised trials 69 CAROL LEFEBVRE, MICHAEL JCLARKE 5 Assessing the quality of randomised controlled trials 87 PETER JÜNI, DOUGLAS G ALTMAN, MATTHIAS EGGER 6 Obtaining individual patient data from randomised controlled trials 109 MICHAEL J CLARKE, LESLEY A STEWART 7 Assessing the quality of reports -

The Existence of Publication Bias and Risk Factors for Its Occurrence

The Existence of Publication Bias and Risk Factors for Its Occurrence Kay Dickersin, PhD Publication bias is the tendency on the parts of investigators, reviewers, and lication, the bias in terms ofthe informa¬ editors to submit or accept manuscripts for publication based on the direction or tion available to the scientific communi¬ strength of the study findings. Much of what has been learned about publication ty may be considerable. The bias that is when of re¬ bias comes from the social sciences, less from the field of medicine. In medicine, created publication study sults is on the direction or three studies have direct evidence for this bias. Prevention of based signifi¬ provided publica- cance of the is called tion bias is both from the scientific dissemina- findings publica¬ important perspective (complete tion bias. This term seems to have been tion of knowledge) and from the perspective of those who combine results from a used first in the published scientific lit¬ number of similar studies (meta-analysis). If treatment decisions are based on erature by Smith1 in 1980. the published literature, then the literature must include all available data that is Even if publication bias exists, is it of acceptable quality. Currently, obtaining information regarding all studies worth worrying about? In a scholarly undertaken in a given field is difficult, even impossible. Registration of clinical sense, it is certainly worth worrying trials, and perhaps other types of studies, is the direction in which the scientific about. If one believes that judgments should move. about medical treatment should be community all (JAMA. -

Mtg2016-Dickersin-References.Pdf

References for NIH Office of Disease Prevention webinar July 25, 2016 Kay Dickersin Slides 1. Pai M, McCulloch M, Gorman JD, et al/ Systematic reviews and meta-analyses. an illustrated, step-by-step guide/ Natl Med J India 2004-17(2).86-95/ 2. Institute of Medicine. Finding what works in health care: standards for systematic reviews. March 23, 2011. Available at: http://www.iom.edu/Reports/2011/Finding-What-Works-in-Health-Care-Standards-for Systematic-Reviews.aspx 3. Institute of Medicine. Clinical practice guidelines we can trust. March 23, 2011. Available at: http://www.nationalacademies.org/hmd/Reports/2011/Clinical-Practice-Guidelines-We Can-Trust.aspx 4. Higgins JPT, Green S. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions (version 5.1.0). Available at: http://www.cochrane-handbook.org/ 5. Dijkers, M. KT Update (Vol. 4, No. 1 – December 2015) Available at: http://ktdrr.org/products/update/v4n1 6. Tricco !, Soobiah C, !ntony J, Cogo E, MacDonald H, Lillie E, Tran J, D’Souza J, Hui W, Perrier L, Welch V, Horsley T, Straus SE, Kastner M. A scoping review identifies multiple emerging knowledge synthesis methods, but few studies operationalize the method. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 73: 19e28. Published online: February 15, 2016. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.08.030 7. Chandler J, Churchill R, Higgins J, Tovey D. Methodological standards for the conduct of new Cochrane Intervention Reviews. Version 2.2. 17 December 2012 – Available at: http://www.editorial-unit.cochrane.org/sites/editorial unit.cochrane.org/files/uploads/MECIR_conduct_standards%202.2%2017122012.pdf 8. -

Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 6.2

Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 6.2 Technical Supplement to Chapter 4: Searching for and selecting studies Trusted evidence. Informed decisions. Better health. Copyright © 2021 The Cochrane Collaboration Technical Supplement to Chapter 4: Searching for and selecting studies Carol Lefebvre, Julie Glanville, Simon Briscoe, Anne Littlewood, Chris Marshall, Maria-Inti Metzendorf, Anna Noel-Storr, Tamara Rader, Farhad Shokraneh, James Thomas and L. Susan Wieland on behalf of the Cochrane Information Retrieval Methods Group This technical supplement should be cited as: Lefebvre C, Glanville J, Briscoe S, Littlewood A, Marshall C, Metzendorf M-I, Noel-Storr A, Rader T, Shokraneh F, Thomas J, Wieland LS. Technical Supplement to Chapter 4: Searching for and selecting studies. In: Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.2 (updated February 2021). Cochrane, 2021. Available from www.training.cochrane.org/handbook. Throughout this technical supplement we refer to the Methodological Expectations of Cochrane Intervention Reviews (MECIR), which are methodological standards to which all Cochrane Protocols, Reviews, and Updates are expected to adhere. More information can be found on these standards at: https://methods.cochrane.org/mecir and, with respect to searching for and selecting studies, in Chapter 4 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Review of Interventions. 1 Sources to search For discussion of CENTRAL, MEDLINE and Embase as the key database sources to search, please refer to Chapter 4, Section 4.3. For discussion of sources other than CENTRAL, MEDLINE and Embase, please see the sections below. -

Sedative-Hypnotic Prescribing in the United States from 1993 to 2010: Recent Trends and Outcomes

SEDATIVE-HYPNOTIC PRESCRIBING IN THE UNITED STATES FROM 1993 TO 2010: RECENT TRENDS AND OUTCOMES by Christopher Norfleet Kaufmann A dissertation submitted to Johns Hopkins University in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Baltimore, Maryland July, 2015 © 2015 Christopher Norfleet Kaufmann All Rights Reserved Abstract BACKGROUND: Studies show sedative-hypnotic medications (benzodiazepines [BZDs] and non-benzodiazepine receptor agonists [nBZRAs]) to be associated with adverse outcomes. This dissertation examined prescribing trends of these medications from 1993-2010, and comprised of three studies: study 1 examined trends in prescribing of sedative-hypnotics, study 2 examined physician practice style as a contributing factor for trends seen in study 1, and study 3 examined visits involving sedative-hypnotics in emergency departments (EDs). METHODS: Data for studies 1 and 2 came from the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NAMCS). Study 1 analyzed trends in the proportion of visits from 1993-2010 where a BZD and/or nBZRA was prescribed. Study 2 examined trends in the proportion of physicians prescribing BZDs and nBZRAs, as well as the predicted number of visits (based on regression models) that a BZD or nBZRA was prescribed among BZD and nBZRA prescribers respectively. Data for study 3 came from the Drug Abuse Warning Network. Analyses used logistic regression to determine the association between ED visits involving BZDs and/or nBZRAs and the seriousness of visit outcomes. RESULTS: From 1993-2010, we found increases in the proportion of visits resulting in a prescription for a BZD (from 2.6% to 4.4%, p<0.001) and a nBZRA (from 0% to 1.4%, p<0.001), as well as the co-prescribing of these agents at the same visit (from 0% to 0.4%, p<0.001). -

Outcomes in Clinical Intervention Research

OUTCOMES IN CLINICAL INTERVENTION RESEARCH: SELECTION, SPECIFICATION, AND REPORTING by Ian Jude Saldanha A dissertation submitted to Johns Hopkins University in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Baltimore, Maryland July, 2015 © 2015 Ian Jude Saldanha All Rights Reserved DISSERTATION ABSTRACT Introduction Sound clinical intervention research relies on the use of the right outcomes dependably and without bias. This dissertation addresses important research gaps related to selection, specification, data collection and analysis, and reporting of outcomes in research. Methods We examined systematic reviews (SRs) and randomized controlled trials (RCTs). For Aim 1, related to outcome selection, we conducted a case study of outcomes in all Cochrane SRs addressing HIV/AIDS (June 2013), to evaluate whether social network analysis methods could be used to identify central outcomes for core outcome sets. For Aim 2, related to outcome specification and data collection and analysis, we examined all Cochrane SR protocols (June 2013) addressing four major eye conditions for completeness of pre-specification and comparability of outcomes. For Aim 3, related to outcome reporting, we examined all conference abstracts of RCTs presented at the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology (ARVO) 2001-2004 conferences to: (1) evaluate agreement in main outcome results comparing abstracts and corresponding full publications, and (2) evaluate the association between conflicts of interest and full publication. ii Results For Aim 1, we applied social network analysis methods to identify central outcomes, and found that the most central outcomes often differed from the most frequent outcomes. For Aim 2, outcome pre-specification in SRs was largely incomplete. -

The Cochrane Collaboration: a Valuable Knowledge Translation Resource

TECHNICAL BRIEF NO. 29 2010 A Publication of the National Center for the Dissemination of Disability Research (NCDDR) Focus The Cochrane Collaboration: A Valuable Knowledge Translation Resource The Cochrane Collaboration has become the premier source worldwide of high-quality systematic reviews in health care. Cochrane’s importance has even been compared to that of the Human Genome Project (Naylor, 1995). The Cochrane Collaboration’s focus on health care applies in many ways to disability and rehabilitation, particularly in the health and function domain. The purpose of this FOCUS Technical Brief is to provide a brief overview of The Cochrane Collaboration and to highlight entities and resources of the Collaboration that can assist disability and rehabilitation researchers and knowledge users in their knowledge translation (KT) efforts. Cochrane Background and Philosophy The Cochrane Collaboration exists for the purpose of Professor making accurate and up-to-date information about Archibald Leman Cochrane CBE FRCP FFCM health-care effects readily available worldwide and (1909–1988) encompasses some 28,000 contributors in more Source: Cardiff University than 100 countries. The Collaboration is named after Library, Cochrane Archive, Professor Archie Cochrane, an epidemiologist who University Hospital Llandough. Retrieved from stressed the importance of properly evaluating health- The Cochrane Collaboration (www.cochrane.org/about- care interventions—particularly through randomized us/history/archie-cochrane) controlled trials —to ensure that limited health-care [Permission not needed.] resources used interventions that were proved to be effective. The Collaboration was formally launched collaboration, avoiding duplication of effort, and in October 1993, and is a registered not-for-profit enabling consumer participation (see Figure 1). -

Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine

Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine http://jrs.sagepub.com/ Recognizing, investigating and dealing with incomplete and biased reporting of clinical research: from Francis Bacon to the WHO Kay Dickersin and Iain Chalmers J R Soc Med 2011 104: 532 DOI: 10.1258/jrsm.2011.11k042 The online version of this article can be found at: http://jrs.sagepub.com/content/104/12/532 Published by: http://www.sagepublications.com On behalf of: The Royal Society of Medicine Additional services and information for Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine can be found at: Email Alerts: http://jrs.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Subscriptions: http://jrs.sagepub.com/subscriptions Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav >> Version of Record - Dec 1, 2011 What is This? Downloaded from jrs.sagepub.com at The Royal Society of Medicine Library on October 14, 2014 FROM THE JAMES LIND LIBRARY Recognizing, investigating and dealing with incomplete and biased reporting of clinical research: from Francis Bacon to the WHO Kay Dickersin1 • Iain Chalmers2 1Department of Epidemiology, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, MD 21205, USA 2The James Lind Initiative, Oxford, UK Correspondence to: Kay Dickersin. Email: [email protected] DECLARATIONS Why is incomplete reporting dissemination. Research results that are not stat- of research a problem? istically significant (‘negative’) tend to be under- Competing interests reported,9 while results that are regarded as excit- None declared Under-reportingoftheresultsofresearchinanyfield ing or statistically significant (‘positive’) tend to be 10 –12 Funding of scientific enquiry is scientific misconduct because over-reported. -

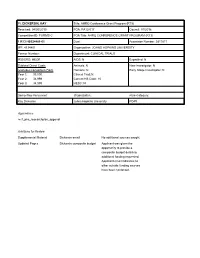

AHRQ Conference Grant Program (Sample)

PI: DICKERSIN, KAY Title: AHRQ Conference Grant Program (R13) Received: 04/30/2015 FOA: PA13-017 Council: 01/2016 Competition ID: FORMS-C FOA Title: AHRQ CONFERENCE GRANT PROGRAM (R13) 1 R13 HS024461-01 Dual: Accession Number: 3817871 IPF: 4134401 Organization: JOHNS HOPKINS UNIVERSITY Former Number: Department: CLINICAL TRIALS IRG/SRG: HEOR AIDS: N Expedited: N Subtotal Direct Costs Animals: N New Investigator: N (excludes consortium F&A) Humans: N Early Stage Investigator: N Year 1: 35,000 Clinical Trial: N Year 2: 34,999 Current HS Code: 10 Year 3: 34,999 HESC: N Senior/Key Personnel: Organization: Role Category: Kay Dickersin Johns Hopkins University PD/PI Appendices m-7_phs_researchplan_appendi Additions for Review Supplemental Material Dickersin email No additional sources sought. Updated Pages Dickersin composite budget Applicant was given the opportunity to provide a composite budget detailing additional funding requested. Applicant email indicates no other outside funding sources have been contacted. OMB Number 4040-0001 Expiration Date 06/30/2016 APPLICATION FOR FEDERAL ASSISTANCE 3. DATE RECEIVED BY STATE State Application Identifier SF 424 (R&R) MD: Maryland 1. TYPE OF SUBMISSION* 4.a. Federal Identifier ❍ Pre-application ● Application ❍ Changed/Corrected b. Agency Routing Number Application 2. DATE SUBMITTED Application Identifier c. Previous Grants.gov Tracking Number 2015-04-30 00071953 5. APPLICANT INFORMATION Organizational DUNS*: 001910777 Legal Name*: Johns Hopkins University Department: CLINICAL TRIALS Division: BLOOMBERG SCHOOL OF PUBLIC HEA Street1*: Bloomberg School of Public Health Street2: 615 N. Wolfe Street, Suite W1600 City*: Baltimore County: State*: MD: Maryland Province: Country*: USA: UNITED STATES ZIP / Postal Code*: 21205-2103 Person to be contacted on matters involving this application Prefix: First Name*: Anthony Middle Name: Edward Last Name*: Jenkins Suffix: Position/Title: Sr. -

CAMARADES: Bringing Evidence to Translational Medicine What Is Research?

Emily Sena, Gillian Currie, Hanna Vesterinen, Kieren Egan, Nicki Sherratt, Cristina Fonseca, Zsannet Bahor, Theo Hirst, Kim Wever, Hugo Pedder, Katerina Kyriacopoulou, Julija Baginskaite, Ye Ru, Stelios Serghiou, Aaron McLean, Catherine Dick, Tracey Woodruff, Patrice Sutton, Andrew Thomson, Aparna Polturu, Sarah MaCann, Gillian Mead, Joanna Wardlaw, Rustam Salman, Joseph Frantzias, Robin Grant, Paul Brennan, Ian Whittle, Andrew Rice, Rosie Moreland, Nathalie Percie du Sert, Paul Garner, Lauralyn McIntyre, Gregers Wegener, Lindsay Thomson, David Howells, Ana Antonic, Tori O’Collins, Uli Dirnagl, H Bart van der Worp, Philip Bath, Mharie McRae, Stuart Allan, Ian Marshall, Xenios Mildonis, Konstantinos Tsilidis, Orestis Panagiotou, John Ioannidis, Peter Batchelor, David Howells, Sanne Jansen of Lorkeers, Geoff Donnan, Peter Sandercock, A Metin Gülmezoglu, Andrew Vickers, An-Wen Chan, Ben Djulbegovic, David Moher,, Davina Ghersi, Douglas G Altman, Elaine Beller, Elina Hemminki, Elizabeth Wager, Fujian Song, Harlan M Krumholz, Iain Chalmers, Ian Roberts, Isabelle Boutron, Janet Wisely, Jonathan Grant, Jonathan Kagan, Julian Savulescu, Kay Dickersin, Kenneth F Schulz, Mark A Hlatky, Michael B Bracken, Mike Clarke, Muin J Khoury, Patrick Bossuyt, Paul Glasziou, Peter C Gøtzsche, Robert S Phillips, Robert Tibshirani, Sander Greenland, SandyDataOliver, Silvio qualityGarattini, Steven andJulious, SusanreproducibilityMichie, Tom Jefferson, Emily Senain , Gillian Currie, Hanna Vesterinen, Kieren Egan, Nicki Sherratt, Cristina Fonseca, Zsannet Bahor, -

Final Research Report

PATIENT-CENTERED OUTCOMES RESEARCH INSTITUTE FINAL RESEARCH REPORT The Benefits and Challenges of Using Multiple Sources of Information about Clinical Trials Kay Dickersin, PhD (Principal investigator), Professor; Evan Mayo-Wilson, MPA, DPhil; Tianjing Li, Assistant Professor AFFILIATION: For the MUDS Investigators, Center for Clinical Trials and Evidence Synthesis, Department of Epidemiology, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, Maryland Original project title: Integrating Multiple Data Sources for Meta-analysis to Improve Patient-Centered Outcomes Research PCORI ID: ME-1303-5785 HSRProj ID: 20143578 _______________ To cite this document, please use: Dickersin K, Mayo-Wilson E, Li T. (2018). The Benefits and Challenges of Using Multiple Sources of Information about Clinical Trials. Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI). https://doi.org/10.25302/3.2018.ME.13035785 TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT ............................................................................................................................. 4 BACKGROUND ....................................................................................................................... 6 Objectives and Overview ........................................................................................................... 6 Patient-Centered Outcomes ...................................................................................................... 6 Reporting Biases ........................................................................................................................