Unity Wetlands Conservation Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

American Eel Distribution and Dam Locations in the Merrymeeting Bay

Seboomook Lake American Eel Distribution and Dam Ripogenus Lake Locations in the Merrymeeting Bay Pittston Farm North East Carry Lobster Lake Watershed (Androscoggin and Canada Falls Lake Rainbow Lake Kennebec River Watersheds) Ragged Lake a d a n Androscoggin River Watershed (3,526 sq. miles) a C Upper section (1,363 sq. miles) South Twin Lake Rockwood Lower section (2,162 sq. miles) Kokadjo Turkey Tail Lake Kennebec River Watershed (6,001 sq. miles) Moosehead Lake Wood Pond Long Pond Long Pond Dead River (879 sq. miles) Upper Jo-Mary Lake Upper Section (1,586 sq. miles) Attean Pond Lower Section (3,446 sq. miles) Number Five Bog Lowelltown Lake Parlin Estuary (90 sq. miles) Round Pond Hydrology; 1:100,000 National Upper Wilson Pond Hydrography Dataset Greenville ! American eel locations from MDIFW electrofishing surveys Spencer Lake " Dams (US Army Corps and ME DEP) Johnson Bog Shirley Mills Brownville Junction Brownville " Monson Sebec Lake Milo Caratunk Eustis Flagstaff Lake Dover-Foxcroft Guilford Stratton Kennebago Lake Wyman Lake Carrabassett Aziscohos Lake Bingham Wellington " Dexter Exeter Corners Oquossoc Rangeley Harmony Kingfield Wilsons Mills Rangeley Lake Solon Embden Pond Lower Richardson Lake Corinna Salem Hartland Sebasticook Lake Newport Phillips Etna " Errol New Vineyard " Madison Umbagog Lake Pittsfield Skowhegan Byron Carlton Bog Upton Norridgewock Webb Lake Burnham e Hinckley Mercer r Farmington Dixmont i h s " Andover e p Clinton Unity Pond n i m a a Unity M H East Pond Wilton Fairfield w e Fowler Bog Mexico N Rumford -

Water Column Summer 2004

Vol. 9, No. 1 Provided free of charge to our monitors and affiliates Summer 2004 Inside Lake Sebasticook Story • Page 8 2004 Life Long Volunteers • Page 16 Maine Lakes 2004 IPP Workshops • Page 18 CONFERENCE VLMP& Annual Meeting June 19 • 8am - 3pm University of Southern Maine, Gorham See Pages 2 & 3 For More Information What’s Inside VLMP ANNUAL MEETING Annual Meeting Overview . 2 Registration . 3 Maine Lakes Lakeside Notes . 4 Recertification Schedule . 5 Littorally Speaking . 6 2004 IPP Workshops . 18 Conference 2004 Lake Sebasticook Story* . 8 Lake Lingo . 11 JUNE 19, 8:00 am - 3:15 pm Culvert Thawing* . 12 University of Southern Maine, Gorham Life Long Volunteers . 16 Brackett Center News Tentative Program Overview Be A Part... 14 MORNING PLENARY SESSION * Volunteer Monitor Articles 8:00 Registration Bailey Hall Lobby 8:25 Welcome - Dan Buckley and Scott Williams 8:40 A Place on Water - Wesley McNair 9:50 Plenary Session Helping Hands: Statewide Resources for Lake Protection and Management 10:00 Refreshment Break 10:15 Recognition and Award Ceremony VLMP Staff 10:45 COLA Annual Meeting Scott Williams Executive Director VLMP Annual Meeting Jim Roby-Brantley Program Assistant Readings from A Place on Water Roberta Hill Program Director Maine Center for 11:30 Lunch Invasive and Aquatic Plants Linda Bacon QA/QC Advisor (Maine DEP) 12:30 Kayak Drawing for VLMP Water Quality Monitors Board of Directors Peter Fischer (Bristol) President 12:45 - 3:10 Afternoon Breakout Sessions Dick Thibodeau (Turner) Vice President Jim Burke (Lewiston) Treasurer -

Inventory of Lake Studies in Maine

University of Southern Maine USM Digital Commons Maine Collection 7-1973 Inventory of Lake Studies in Maine Charles F. Wallace Jr. James M. Strunk Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usm.maine.edu/me_collection Part of the Biology Commons, Environmental Health Commons, Environmental Indicators and Impact Assessment Commons, Environmental Monitoring Commons, Hydrology Commons, Marine Biology Commons, Natural Resources and Conservation Commons, Natural Resources Management and Policy Commons, Other Life Sciences Commons, and the Terrestrial and Aquatic Ecology Commons Recommended Citation Wallace, Charles F. Jr. and Strunk, James M., "Inventory of Lake Studies in Maine" (1973). Maine Collection. 134. https://digitalcommons.usm.maine.edu/me_collection/134 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by USM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Maine Collection by an authorized administrator of USM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INVENTORY OF LAKE STUDIES IN MAINE By Charles F. Wallace, Jr. and James m. Strunk ,jitnt.e of ~lame Zfrxemtiue ~epnrlmeut ~fate Jhtuuiug ®£fit£ 189 ~fate ~treet, !>ugusht, ~nine 04330 KENNETH M. CURTIS WATER RESOURCES PLANNING GOVERNOR 16 WINTHROP STREET PHILIP M. SAVAGE TEL. ( 207) 289-3253 STATE PLANNING DIRECTOR July 16, 1973 Please find enclosed a copy of the Inventory of Lake Studies in Maine prepared by the Water Resources Planning Unit of the State Planning Office. We hope this will enable you to better understand the intensity and dir ection of lake studies and related work at various private and institutional levels in the State of Maine. Any comments or inquiries, which you may have concerning its gerieral content or specific studies, are welcomed. -

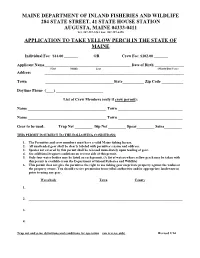

Application to Take Yellow Perch in the State of Maine

MAINE DEPARTMENT OF INLAND FISHERIES AND WILDLIFE 284 STATE STREET, 41 STATE HOUSE STATION AUGUSTA, MAINE 04333-0411 Tel: 207-287-5261 Fax: 207-287-6395 APPLICATION TO TAKE YELLOW PERCH IN THE STATE OF MAINE Individual Fee: $44.00 _______ OR Crew Fee: $102.00 _______ Applicant Name____________________________________________ Date of Birth _______________ First Middle Last (Month/Day/Year) Address _______________________________________________________________________ Town ___________________________________State___________ Zip Code ___________ Daytime Phone (____) ________________________ List of Crew Members (only if crew permit): Name ________________________________________ Town _________________________________ Name ________________________________________ Town _________________________________ Gear to be used: Trap Net _________ Dip Net _________ Spear_________ Seine_________ THIS PERMIT IS SUBJECT TO THE FOLLOWING CONDITIONS: 1. The Permittee and crew members must have a valid Maine fishing license. 2. All unattended gear shall be clearly labeled with permittee’s name and address. 3. Species not covered by this permit shall be released immediately upon tending of gear. 4. See additional trapnet conditions on reverse side of this permit. 5. Only four water bodies may be listed on each permit. (A list of waters where yellow perch may be taken with this permit is available from the Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife) 6. This permit does not give the permittee the right to use fishing gear on private property against the wishes -

The Water C Lumn

NON-PROFIT U.S. POSTAGE PAID the Lewiston, ME Permit # 82 Water C lumn ADDRESS SERVICE REQUESTED The Newsletter of Lake Stewards of Maine - Volunteer Lake Monitoring Program Vol. 23, No. 1 Celebrating the Work of Maine's Citizen Lake Stewards Winter 2018-19 Climate Change... What can you find onwww.LakesOfMaine.org ? And Lakes Search lakes throughout the State of Maine and discover… • Physical characteristics • Fish, wildlife and plant diversity • Water quality, present and historical • Invasive aquatic species survey findings • Active Lake Stewards throughout Maine • Maps of all types • Conservation efforts in lake watersheds • Watershed management efforts • Published lake research documents • Graphic representation of lake data And much more! 36 What’s Inside : President's Message . 2 Lakeside Notes . 3 President’s Littorally Speaking ~ Invasive Species & Climate Change . 4 Quality Counts . 6 Under the Hand Lens ~ European Frog-bit . 7 Connecting the Drops ~ LSM Sustainability . 8 Message Development Team Tidbits . 9 Citizen Lake Science: Water Quality & Climate Change . 10 Bill Monagle IPP Notes from the Front Lines . 12 President, LSM Board of Directors Near Real-Time Lake Data . 15 Tips For IPPers . 16 ake Stewards of Maine the full board meets 5 times/year, Seeking Board Members . 17 L(LSM) is a fitting new name but the schedule for individual Thank You to our Generous Donors! . 18 for our organization. It speaks subcommittee meetings (in-person Beyond Clean, Drain, Dry: Advanced Protocols . 21 directly to the awesome efforts of or virtually) may take place on an Maine Lakes Water Quality Year in Review . 22 Matt Scott - Goodwill Lake Ambassador . -

Waterville Caniba Naturals

in Maine June 6, 2018 Special Advertising Supplement Kennebec Journal Morning Sentinel 2 Wednesday, June 6, 2018 _______________________________________________________Advertising Supplement • Kennebec Journal • Morning Sentinel INDEX OF ADVERTISERS AUTOMOTIVE CANNABIS CONNECTION St. Joseph Maronite Catholic Columbia Classic Cars...................13 Cannabis Connection Directories 70-71 Church ..........................................65 Skowhegan & Waterville Caniba Naturals ..............................70 St. Mary............................................65 Tire Center ....................................26 Cannabis Healing Center, The .......70 St. Michael Parish ...........................65 Father Jimmy’s ...............................70 Sugarloaf Christian Ministry ..........65 ANIMALS & Harry Brown’s Farm .......................70 Summer Worship Directory ...........65 PETS Homegrown Healthcare Union Church of Belgrade Lakes Paws and Claws........................19, 57 Apothecary & Learning Center ...71 United Methodist Church ............65 Companion Animal Clinic ..............57 Integr8 Health..................................70 Unity United Methodist Church .....65 Hometown Veterinary Care ............57 Limited Edition Farm, LLC - Vassalboro United Methodist Kennebec Veterinary Care .............57 Medical Marijuana........................71 Church ..........................................65 Veterinary and Kennel Directory ..... 57 Maja’s ...............................................71 Waterville First Baptist Church -

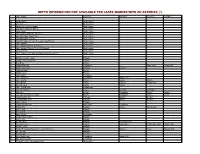

Depth Information Not Available for Lakes Marked with an Asterisk (*)

DEPTH INFORMATION NOT AVAILABLE FOR LAKES MARKED WITH AN ASTERISK (*) LAKE NAME COUNTY COUNTY COUNTY COUNTY GL Great Lakes Great Lakes GL Lake Erie Great Lakes GL Lake Erie (Port of Toledo) Great Lakes GL Lake Erie (Western Basin) Great Lakes GL Lake Huron Great Lakes GL Lake Huron (w West Lake Erie) Great Lakes GL Lake Michigan (Northeast) Great Lakes GL Lake Michigan (South) Great Lakes GL Lake Michigan (w Lake Erie and Lake Huron) Great Lakes GL Lake Ontario Great Lakes GL Lake Ontario (Rochester Area) Great Lakes GL Lake Ontario (Stoney Pt to Wolf Island) Great Lakes GL Lake Superior Great Lakes GL Lake Superior (w Lake Michigan and Lake Huron) Great Lakes AL Baldwin County Coast Baldwin AL Cedar Creek Reservoir Franklin AL Dog River * Mobile AL Goat Rock Lake * Chambers Lee Harris (GA) Troup (GA) AL Guntersville Lake Marshall Jackson AL Highland Lake * Blount AL Inland Lake * Blount AL Lake Gantt * Covington AL Lake Jackson * Covington Walton (FL) AL Lake Jordan Elmore Coosa Chilton AL Lake Martin Coosa Elmore Tallapoosa AL Lake Mitchell Chilton Coosa AL Lake Tuscaloosa Tuscaloosa AL Lake Wedowee Clay Cleburne Randolph AL Lay Lake Shelby Talladega Chilton Coosa AL Lay Lake and Mitchell Lake Shelby Talladega Chilton Coosa AL Lewis Smith Lake Cullman Walker Winston AL Lewis Smith Lake * Cullman Walker Winston AL Little Lagoon Baldwin AL Logan Martin Lake Saint Clair Talladega AL Mobile Bay Baldwin Mobile Washington AL Mud Creek * Franklin AL Ono Island Baldwin AL Open Pond * Covington AL Orange Beach East Baldwin AL Oyster Bay Baldwin AL Perdido Bay Baldwin Escambia (FL) AL Pickwick Lake Colbert Lauderdale Tishomingo (MS) Hardin (TN) AL Shelby Lakes Baldwin AL Walter F. -

Maine Inland Ice Fishing Laws : 1939 Revision Maine Department of Inland Fisheries and Game

Maine State Library Digital Maine Inland Fisheries and Wildlife Law Books Inland Fisheries and Wildlife 4-22-1939 Maine Inland Ice Fishing Laws : 1939 Revision Maine Department of Inland Fisheries and Game Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalmaine.com/ifw_law_books Recommended Citation Maine Department of Inland Fisheries and Game, "Maine Inland Ice Fishing Laws : 1939 Revision" (1939). Inland Fisheries and Wildlife Law Books. 66. https://digitalmaine.com/ifw_law_books/66 This Text is brought to you for free and open access by the Inland Fisheries and Wildlife at Digital Maine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Inland Fisheries and Wildlife Law Books by an authorized administrator of Digital Maine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Y v Maine INLAND ICE FISHING LAWS 19 3 9 REVISION ICE FISHING LAWS The waters* listed by Counties, in this pamphlet are separated into groups which are governed by the same laws GENERAL LAW Except as otherwise specified herein, it Is illegal to fish bai_any_Jtmd_^f_fish_Jn^va2er«_»vhicli_are_closed^o_fishin^ for salmon, trout and togue. Bass cannot be taken through tTTT ice at any time, Persons properly licensed may fish through the ice in the daytime with 5 set lines each, when under the immediate supervision of the person fishing, and *n the night-time for cusk in such waters as are open forfiah- ing in the night time for cusk. Non-residents over 10 years of age and residents over 18 years of age must be licensed. Sec, 27. Fishing for gain or hire prohibited! exceptions! JMialty. Whoever shall, for the whole or any part of the time, engage in the business or occupation of fishing in any of the inland waters of the state above tide-waters, for salmon, togue, trout, black bass, pickerel, or white perch, for gain or hire, shall for every such offense pay a fine of $50 and costs, except that pickerel legally taken in the County of Washington may be sold by the person tak ing the same. -

Rfq) Planning Consultant Services for Impaired Lake Watershed Plan Development

WALDO COUNTY SOIL AND WATER CONSERVATION DISTRICT REQUEST FOR QUALIFICATIONS (RFQ) PLANNING CONSULTANT SERVICES FOR IMPAIRED LAKE WATERSHED PLAN DEVELOPMENT The Waldo County Soil and Water Conservation District (District) is requesting Statements of Qualifications from interested and qualified Consultants for Professional Planning Consultant Services in order to assist in the development of an update to the Unity Pond (Lake Winnecook) Watershed-Based Management Plan. The purpose of the Unity Pond (Lake Winnecook) Watershed-Based Management Plan Project is to create a comprehensive plan for Unity Pond (Lake Winnecook) with well-developed implementation strategies that effectively improve the water quality of the lake over the next 10 years Overview The District has been awarded a grant and is under contract with the Maine DEP to develop a watershed-based plan for the Pond (Lake). Funds for this project were provided by the USEPA under Section 319 of the Clean Water Act. Unity Pond sits at 175 feet above sea level. The pond has a maximum depth of 12 meters (41 feet), an average depth of 6 meters (19 feet), and an estimated volume of 57,959,154 m3. The pond flushes 1.23 times per year.i The watershed is drained by three major tributaries- Meadow Brook, Bithers (bog) Brook, and Carlton Stream. Meadow Brook originates in the western watershed in a large tamarack bog complex, Bithers Brook flows from the east, and Carlton Stream flows from the north at the outlet of Carlton Pond (a.k.a. Carlton Bog). A single outlet, Sandy Stream, is located at the southern end of the pond. -

Maine Inland Ice Fishing Laws : 1938 Maine Department of Inland Fisheries and Game

Maine State Library Digital Maine Inland Fisheries and Wildlife Law Books Inland Fisheries and Wildlife 4-21-1938 Maine Inland Ice Fishing Laws : 1938 Maine Department of Inland Fisheries and Game Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalmaine.com/ifw_law_books Recommended Citation Maine Department of Inland Fisheries and Game, "Maine Inland Ice Fishing Laws : 1938" (1938). Inland Fisheries and Wildlife Law Books. 65. https://digitalmaine.com/ifw_law_books/65 This Text is brought to you for free and open access by the Inland Fisheries and Wildlife at Digital Maine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Inland Fisheries and Wildlife Law Books by an authorized administrator of Digital Maine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Maine INLAND ICE FISHING LAWS 1 9 3 8 V ’ * I 1 ^ ^ • ICE FISHING LAWS The waters, listed by Counties, in this pamphlet are separated into groups which are governed by the same laws GENERAL LAW Except as otherwise specified herein, it is illegal to fish for any kind of fish in waters which are closed to fishing for salmon, trout and togue. Bass cannot be taken through the ice at any time. Persons properly licensed may lish through the ice in the daytime with 5 set lines each, when under the immediate supervision of the person fishing, and in the night time for cusk in such waters as are open for fish ing in the night time for cusk. Non-residents over 10 years of age and residents over 18 years of age m ust be licensed. Sec. 27. Fishing for gain or hire prohibited; exceptions; penalty. -

¨§¦95 ¨§¦95 ¨§¦95

Ä Ä Ä Ä k 173 216 e Churchill Lake Ä Ä A r o o s t o o k Maine Mountain Collaboration for Fish and WildlifeMunsungan 204 Lake Grand Lake Eagle Lake Sebois Western Maine, 2.26 million acres Millinocket Allagash Lake Branch Lake Millimagassett ast E cot River Lake obs RCPP Project Area Baker Lake Pen Indian Pond Cha mb Caucomgomoc erl ain Lake La ke Matagamon Mud Pond Lakes Umbazooksus Lake Black Pond Loon Lake Brandy Pond Chesuncook Lake Matta Seboomook Lake Penobscot Lake Caribou Lake A r o o s t o o k PRENTISS TWP, Lobster Lake Canada Somerset Falls Lake BALD ¤£201 Ragged Lake Millinocket SANDY MOUNTAIN Lake BAY TWP TWP T4 R3 Spencer Pond Pemadumcook Molunkus Lake Brassua Chain Lake Ä MOOSE Jo-Mary Ä Lake DENNISTOWN RIVER Lake Dolby Pond §95 First ¦¨ 204 FORSYTH PLT Moose Moosehead Roach Pond River Lake TWP Long P LONG Quakish Lake enob Wood Pond Pond scot POND TWP Riv JACKMAN er GORHAM GORE Holeb Pond MISERY GORE TWP Jo-Mary Lake kea g HOLEB TWP m ATTEAN TWP w a tta LOWELLTOWN Attean Pond MISERY TWP a PARLIN Indian East Branch Lake M TWP BRADSTREET POND TWP Pond T5 R7 Seboeis Lake BEATTIE TWP TWP CHASE APPLETON BKP WKR Endless P e n o b s c o t JOHNSON STREAM Lake Mattamiscontis TWP Lake MOUNTAIN TWP Lower Wilson Pond MERRILL SKINNER UPPER STRIP TWP ENCHANTED TWP Ä TWP Ä HOBBSTOWN T5 R6 TWP e Ä TWP k South Ä BKP WKR a COBURN GORE WEST L Branch Lake c 161 LOWER i 6 Spencer Lake Lake d FORKS PLT o ST MERRILL STRIP TWP o ENCHANTED Onawa h Piscataquis c 212 S KIBBY TWP TWP Moxie CHAIN OF T3 R5 KING Pond PONDS TWP BKP WKR BOWTOWN TWP ata -

Chapter 3 Existing Environment

Chapter 3 Dan Salas, Cardno JFNew Dan Salas, Cardno View of Carlton Pond Existing Environment • Introduction • Physical Landscape • Refuge and WPA Biological Resources • Cultural Landscape Setting and Land Use History • Socioeconomic Environment • Refuge and WPA Administration • Refuge and WPA Public Use • Archaeological and Historical Resources Introduction Introduction This chapter describes the current and historic physical, biological, and socioeconomic landscape of Carlton Pond WPA and the three units comprising Sunkhaze Meadows NWR (Sunkhaze Meadows, Benton, and Sandy Stream Units). Included are descriptions of the physical landscape, the regional context and its history, and the refuge environment, including its history, current administration, programs, and specific refuge resources. The 11,484-acre Sunkhaze Meadows Unit is located in the town of Milford, Penobscot County, approximately 14 miles northeast of Bangor, Maine. The refuge is about 3 miles east of the Penobscot River and roughly bounded on the west by Dudley Brook, on the south and east by County Road, and on the north and east by Stud Mill Road. Sunkhaze Stream bisects the refuge along a northeast to southwest orientation and, along with its six tributaries, creates a diversity of wetland communities. The bogs and stream wetlands, adjacent uplands and associated transition zones, provide important habitat for many wildlife species. The wetland complex consists primarily of wet meadows, shrub thickets, cedar swamps, extensive red and silver maple floodplain forests and open freshwater stream habitats, along with plant communities associated with peatlands, such as shrub heaths and cedar and spruce bogs. The 334-acre Benton Unit is in the town of Benton, Kennebec County, about 5 miles northeast of Waterville, Maine.