Maine Loon Mortality: 1987-2012

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Following Document Comes to You From

MAINE STATE LEGISLATURE The following document is provided by the LAW AND LEGISLATIVE DIGITAL LIBRARY at the Maine State Law and Legislative Reference Library http://legislature.maine.gov/lawlib Reproduced from scanned originals with text recognition applied (searchable text may contain some errors and/or omissions) ACTS AND RESOLVES AS PASSED BY THE Ninetieth and Ninety-first Legislatures OF THE STATE OF MAINE From April 26, 1941 to April 9, 1943 AND MISCELLANEOUS STATE PAPERS Published by the Revisor of Statutes in accordance with the Resolves of the Legislature approved June 28, 1820, March 18, 1840, March 16, 1842, and Acts approved August 6, 1930 and April 2, 193I. KENNEBEC JOURNAL AUGUSTA, MAINE 1943 PUBLIC LAWS OF THE STATE OF MAINE As Passed by the Ninety-first Legislature 1943 290 TO SIMPLIFY THE INLAND FISHING LAWS CHAP. 256 -Hte ~ ~ -Hte eOt:l:llty ffi' ft*; 4tet s.e]3t:l:ty tfl.a.t mry' ~ !;;llOWR ~ ~ ~ ~ "" hunting: ffi' ftshiRg: Hit;, ffi' "" Hit; ~ mry' ~ ~ ~, ~ ft*; eounty ~ ft8.t rett:l:rRes. ~ "" rC8:S0R8:B~e tffi:re ~ ft*; s.e]38:FtaFe, ~ ~ ffi" 5i:i'ffi 4tet s.e]3uty, ~ 5i:i'ffi ~ a-5 ~ 4eeme ReCCSS8:F)-, ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ffi'i'El, 4aH ~ eRtitles. 4E; Fe8:50nable fee5 ffi'i'El, C!E]3C::lSCS ~ ft*; sen-ices ffi'i'El, ~ ft*; ffi4s, ~ ~ ~ ~ -Hte tFeasurcr ~ ~ eouRty. BefoFc tfte sffi4 ~ €of' ~ ~ 4ep i:tt;- ~ ffle.t:J:.p 8:s.aitional e1E]3cfisc itt -Hte eM, ~ -Hte ~ ~~' ~, ftc ~ ~ -Hte conseRt ~"" lIiajority ~ -Hte COt:l:fity COfi111'lissioReFs ~ -Hte 5a+4 coufity. Whenever it shall come to the attention of the commis sioner -

American Eel Distribution and Dam Locations in the Merrymeeting Bay

Seboomook Lake American Eel Distribution and Dam Ripogenus Lake Locations in the Merrymeeting Bay Pittston Farm North East Carry Lobster Lake Watershed (Androscoggin and Canada Falls Lake Rainbow Lake Kennebec River Watersheds) Ragged Lake a d a n Androscoggin River Watershed (3,526 sq. miles) a C Upper section (1,363 sq. miles) South Twin Lake Rockwood Lower section (2,162 sq. miles) Kokadjo Turkey Tail Lake Kennebec River Watershed (6,001 sq. miles) Moosehead Lake Wood Pond Long Pond Long Pond Dead River (879 sq. miles) Upper Jo-Mary Lake Upper Section (1,586 sq. miles) Attean Pond Lower Section (3,446 sq. miles) Number Five Bog Lowelltown Lake Parlin Estuary (90 sq. miles) Round Pond Hydrology; 1:100,000 National Upper Wilson Pond Hydrography Dataset Greenville ! American eel locations from MDIFW electrofishing surveys Spencer Lake " Dams (US Army Corps and ME DEP) Johnson Bog Shirley Mills Brownville Junction Brownville " Monson Sebec Lake Milo Caratunk Eustis Flagstaff Lake Dover-Foxcroft Guilford Stratton Kennebago Lake Wyman Lake Carrabassett Aziscohos Lake Bingham Wellington " Dexter Exeter Corners Oquossoc Rangeley Harmony Kingfield Wilsons Mills Rangeley Lake Solon Embden Pond Lower Richardson Lake Corinna Salem Hartland Sebasticook Lake Newport Phillips Etna " Errol New Vineyard " Madison Umbagog Lake Pittsfield Skowhegan Byron Carlton Bog Upton Norridgewock Webb Lake Burnham e Hinckley Mercer r Farmington Dixmont i h s " Andover e p Clinton Unity Pond n i m a a Unity M H East Pond Wilton Fairfield w e Fowler Bog Mexico N Rumford -

Maine Boating 2008 Laws & Rules

Maine State Library Maine State Documents Inland Fisheries and Wildlife Law Books Inland Fisheries and Wildlife 1-1-2008 Maine Boating 2008 Laws & Rules Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalmaine.com/ifw_law_books Recommended Citation "Maine Boating 2008 Laws & Rules" (2008). Inland Fisheries and Wildlife Law Books. 479. http://digitalmaine.com/ifw_law_books/479 This Text is brought to you for free and open access by the Inland Fisheries and Wildlife at Maine State Documents. It has been accepted for inclusion in Inland Fisheries and Wildlife Law Books by an authorized administrator of Maine State Documents. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STATE OF MAINE BOATING 2008 LAW S & RU L E S www.maine.gov/ifw STATE OF MAINE BOATING 2008 LAW S & RU L E S www.maine.gov/ifw MESSAGE FROM THE GOVERNOR & COMMISSIONER With an impressive inventory of 6,000 lakes and ponds, 3,000 miles of coastline, and over 32,000 miles of rivers and streams, Maine is truly a remarkable place for you to launch your boat and enjoy the variety and beauty of our waters. Providing public access to these bodies of water is extremely impor- tant to us because we want both residents and visitors alike to enjoy them to the fullest. The Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife works diligently to provide access to Maine’s waters, whether it’s a remote mountain pond, or Maine’s Casco Bay. How you conduct yourself on Maine’s waters will go a long way in de- termining whether new access points can be obtained since only a fraction of our waters have dedicated public access. -

STATE of MAINE EXECUTIVE DEPARTMENT STATE PLANNIJ'\G OFFICE 38 STATE HOUSE STATION AUGUSTA, MAINE 043 3 3-003Fi ANGUS S

MAINE STATE LEGISLATURE The following document is provided by the LAW AND LEGISLATIVE DIGITAL LIBRARY at the Maine State Law and Legislative Reference Library http://legislature.maine.gov/lawlib Reproduced from scanned originals with text recognition applied (searchable text may contain some errors and/or omissions) Great Pond Tasl< Force Final Report KF 5570 March 1999 .Z99 Prepared by Maine State Planning Office I 84 ·State Street Augusta, Maine 04333 Acknowledgments The Great Pond Task Force thanks Hank Tyler and Mark DesMeules for the staffing they provided to the Task Force. Aline Lachance provided secretarial support for the Task Force. The Final Report was written by Hank Tyler. Principal editing was done by Mark DesMeules. Those offering additional editorial and layout assistance/input include: Jenny Ruffing Begin and Liz Brown. Kevin Boyle, Jennifer Schuetz and JefferyS. Kahl of the University of Maine prepared the economic study, Great Ponds Play an Integral Role in Maine's Economy. Frank O'Hara of Planning Decisions prepared the Executive Summary. Larry Harwood, Office of GIS, prepared the maps. In particular, the Great Pond Task Force appreciates the effort made by all who participated in the public comment phase of the project. D.D.Tyler donated the artwork of a Common Loon (Gavia immer). Copyright Diana Dee Tyler, 1984. STATE OF MAINE EXECUTIVE DEPARTMENT STATE PLANNIJ'\G OFFICE 38 STATE HOUSE STATION AUGUSTA, MAINE 043 3 3-003fi ANGUS S. KING, JR. EVAN D. RICHERT, AICP GOVERNOR DIRECTOR March 1999 Dear Land & Water Resources Council: Maine citizens have spoken loud and clear to the Great Pond Task Force about the problems confronting Maine's lakes and ponds. -

Water Column Summer 2004

Vol. 9, No. 1 Provided free of charge to our monitors and affiliates Summer 2004 Inside Lake Sebasticook Story • Page 8 2004 Life Long Volunteers • Page 16 Maine Lakes 2004 IPP Workshops • Page 18 CONFERENCE VLMP& Annual Meeting June 19 • 8am - 3pm University of Southern Maine, Gorham See Pages 2 & 3 For More Information What’s Inside VLMP ANNUAL MEETING Annual Meeting Overview . 2 Registration . 3 Maine Lakes Lakeside Notes . 4 Recertification Schedule . 5 Littorally Speaking . 6 2004 IPP Workshops . 18 Conference 2004 Lake Sebasticook Story* . 8 Lake Lingo . 11 JUNE 19, 8:00 am - 3:15 pm Culvert Thawing* . 12 University of Southern Maine, Gorham Life Long Volunteers . 16 Brackett Center News Tentative Program Overview Be A Part... 14 MORNING PLENARY SESSION * Volunteer Monitor Articles 8:00 Registration Bailey Hall Lobby 8:25 Welcome - Dan Buckley and Scott Williams 8:40 A Place on Water - Wesley McNair 9:50 Plenary Session Helping Hands: Statewide Resources for Lake Protection and Management 10:00 Refreshment Break 10:15 Recognition and Award Ceremony VLMP Staff 10:45 COLA Annual Meeting Scott Williams Executive Director VLMP Annual Meeting Jim Roby-Brantley Program Assistant Readings from A Place on Water Roberta Hill Program Director Maine Center for 11:30 Lunch Invasive and Aquatic Plants Linda Bacon QA/QC Advisor (Maine DEP) 12:30 Kayak Drawing for VLMP Water Quality Monitors Board of Directors Peter Fischer (Bristol) President 12:45 - 3:10 Afternoon Breakout Sessions Dick Thibodeau (Turner) Vice President Jim Burke (Lewiston) Treasurer -

China Lake Characterisitcs

CHINA LAKE CHARACTERISITCS WATERSHED DESCRIPTION The China Lake watershed is located in Kennebec County, Maine, and is situated within the townships of China, Vassalboro, and Albion (Figure 8). The lake is classified by the Maine Information Display Analysis System (MIDAS) as MIDAS #5448 (PEARL 2005a). This classification system assigns unique four-digit codes to identify all lakes and ponds in Maine. China Lake is located 44.25° N and 69.33° W, at an elevation of 59.1 m (194 ft), and covers a surface area of 1,604 ha (3,963 acres) (PEARL 2005a). China is classified geographically as a two basin lake, with an East Basin and West Basin (PEARL 2005a). Bathymetrically, China Lake is described as a three basin lake, with three deep holes forming the western, southeastern, and northeastern basins (Manthey, pers. comm.). China Lake has an average depth of 10.1 m (33.1 ft), a maximum depth of 28.2 m (92.4 ft), and a volume of 120,001,704 m3 (97,286.4 acre- ft) (PEARL 2005a). The water within China Lake flows from input to output at an annual rate of 0.35 flushes per year. There are several small islands within China Lake, most notably Indian Island, Green Island, Bradley Island, and Moody Island. China Lake is dimictic, experiencing thermal stratification in the summer with turnovers occurring each spring and fall. Algal blooms have been reported yearly since 1983 and the Maine Department of Environmental Protection (MDEP) currently describes China Lake as a “frequently blooming” lake. This classification means that the lake commonly experiences late summer and early fall reductions in water transparency due to algal blooms (MDEP 2005a). -

Inventory of Lake Studies in Maine

University of Southern Maine USM Digital Commons Maine Collection 7-1973 Inventory of Lake Studies in Maine Charles F. Wallace Jr. James M. Strunk Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usm.maine.edu/me_collection Part of the Biology Commons, Environmental Health Commons, Environmental Indicators and Impact Assessment Commons, Environmental Monitoring Commons, Hydrology Commons, Marine Biology Commons, Natural Resources and Conservation Commons, Natural Resources Management and Policy Commons, Other Life Sciences Commons, and the Terrestrial and Aquatic Ecology Commons Recommended Citation Wallace, Charles F. Jr. and Strunk, James M., "Inventory of Lake Studies in Maine" (1973). Maine Collection. 134. https://digitalcommons.usm.maine.edu/me_collection/134 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by USM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Maine Collection by an authorized administrator of USM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INVENTORY OF LAKE STUDIES IN MAINE By Charles F. Wallace, Jr. and James m. Strunk ,jitnt.e of ~lame Zfrxemtiue ~epnrlmeut ~fate Jhtuuiug ®£fit£ 189 ~fate ~treet, !>ugusht, ~nine 04330 KENNETH M. CURTIS WATER RESOURCES PLANNING GOVERNOR 16 WINTHROP STREET PHILIP M. SAVAGE TEL. ( 207) 289-3253 STATE PLANNING DIRECTOR July 16, 1973 Please find enclosed a copy of the Inventory of Lake Studies in Maine prepared by the Water Resources Planning Unit of the State Planning Office. We hope this will enable you to better understand the intensity and dir ection of lake studies and related work at various private and institutional levels in the State of Maine. Any comments or inquiries, which you may have concerning its gerieral content or specific studies, are welcomed. -

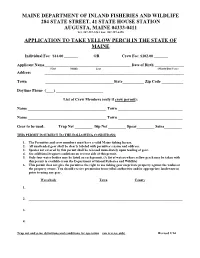

Application to Take Yellow Perch in the State of Maine

MAINE DEPARTMENT OF INLAND FISHERIES AND WILDLIFE 284 STATE STREET, 41 STATE HOUSE STATION AUGUSTA, MAINE 04333-0411 Tel: 207-287-5261 Fax: 207-287-6395 APPLICATION TO TAKE YELLOW PERCH IN THE STATE OF MAINE Individual Fee: $44.00 _______ OR Crew Fee: $102.00 _______ Applicant Name____________________________________________ Date of Birth _______________ First Middle Last (Month/Day/Year) Address _______________________________________________________________________ Town ___________________________________State___________ Zip Code ___________ Daytime Phone (____) ________________________ List of Crew Members (only if crew permit): Name ________________________________________ Town _________________________________ Name ________________________________________ Town _________________________________ Gear to be used: Trap Net _________ Dip Net _________ Spear_________ Seine_________ THIS PERMIT IS SUBJECT TO THE FOLLOWING CONDITIONS: 1. The Permittee and crew members must have a valid Maine fishing license. 2. All unattended gear shall be clearly labeled with permittee’s name and address. 3. Species not covered by this permit shall be released immediately upon tending of gear. 4. See additional trapnet conditions on reverse side of this permit. 5. Only four water bodies may be listed on each permit. (A list of waters where yellow perch may be taken with this permit is available from the Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife) 6. This permit does not give the permittee the right to use fishing gear on private property against the wishes -

The Water C Lumn

NON-PROFIT U.S. POSTAGE PAID the Lewiston, ME Permit # 82 Water C lumn ADDRESS SERVICE REQUESTED The Newsletter of Lake Stewards of Maine - Volunteer Lake Monitoring Program Vol. 23, No. 1 Celebrating the Work of Maine's Citizen Lake Stewards Winter 2018-19 Climate Change... What can you find onwww.LakesOfMaine.org ? And Lakes Search lakes throughout the State of Maine and discover… • Physical characteristics • Fish, wildlife and plant diversity • Water quality, present and historical • Invasive aquatic species survey findings • Active Lake Stewards throughout Maine • Maps of all types • Conservation efforts in lake watersheds • Watershed management efforts • Published lake research documents • Graphic representation of lake data And much more! 36 What’s Inside : President's Message . 2 Lakeside Notes . 3 President’s Littorally Speaking ~ Invasive Species & Climate Change . 4 Quality Counts . 6 Under the Hand Lens ~ European Frog-bit . 7 Connecting the Drops ~ LSM Sustainability . 8 Message Development Team Tidbits . 9 Citizen Lake Science: Water Quality & Climate Change . 10 Bill Monagle IPP Notes from the Front Lines . 12 President, LSM Board of Directors Near Real-Time Lake Data . 15 Tips For IPPers . 16 ake Stewards of Maine the full board meets 5 times/year, Seeking Board Members . 17 L(LSM) is a fitting new name but the schedule for individual Thank You to our Generous Donors! . 18 for our organization. It speaks subcommittee meetings (in-person Beyond Clean, Drain, Dry: Advanced Protocols . 21 directly to the awesome efforts of or virtually) may take place on an Maine Lakes Water Quality Year in Review . 22 Matt Scott - Goodwill Lake Ambassador . -

Historical Ice-Out Dates for 29 Lakes in New England, 1807–2008

Historical Ice-Out Dates for 29 Lakes in New England, 1807–2008 Open-File Report 2010–1214 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Cover. Photograph shows ice-out on Jordan Bay, Sebago Lake, Maine, Spring 1985. Historical Ice-Out Dates for 29 Lakes in New England, 1807–2008 By Glenn A. Hodgkins Open-File Report 2010–1214 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior KEN SALAZAR, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Marcia K. McNutt, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2010 For product and ordering information: World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment: World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS Suggested citation: Hodgkins, G.A., 2010, Historical ice-out dates for 29 lakes in New England, 1807–2008: U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 2010–1214, 32 p., at http://pubs.usgs.gov/of/2010/1214/. Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this report is in the public domain, permission must be secured from the individual copyright owners to reproduce any copyrighted material contained within this report. ii Contents Abstract ........................................................................................................................................................................ -

Waterville Caniba Naturals

in Maine June 6, 2018 Special Advertising Supplement Kennebec Journal Morning Sentinel 2 Wednesday, June 6, 2018 _______________________________________________________Advertising Supplement • Kennebec Journal • Morning Sentinel INDEX OF ADVERTISERS AUTOMOTIVE CANNABIS CONNECTION St. Joseph Maronite Catholic Columbia Classic Cars...................13 Cannabis Connection Directories 70-71 Church ..........................................65 Skowhegan & Waterville Caniba Naturals ..............................70 St. Mary............................................65 Tire Center ....................................26 Cannabis Healing Center, The .......70 St. Michael Parish ...........................65 Father Jimmy’s ...............................70 Sugarloaf Christian Ministry ..........65 ANIMALS & Harry Brown’s Farm .......................70 Summer Worship Directory ...........65 PETS Homegrown Healthcare Union Church of Belgrade Lakes Paws and Claws........................19, 57 Apothecary & Learning Center ...71 United Methodist Church ............65 Companion Animal Clinic ..............57 Integr8 Health..................................70 Unity United Methodist Church .....65 Hometown Veterinary Care ............57 Limited Edition Farm, LLC - Vassalboro United Methodist Kennebec Veterinary Care .............57 Medical Marijuana........................71 Church ..........................................65 Veterinary and Kennel Directory ..... 57 Maja’s ...............................................71 Waterville First Baptist Church -

Maine Woods, Phillips, Maine, May 8, 1913

MAINE WOODS, PHILLIPS, MAINE, MAY 8, 1913 Number of square-tailed trout eggs taken at this hatch ery fall of 1911, 106,000 Received from American Fish 5 out of 6 REVOLVER Cul ure Co., Carolina, R. I., , eggs that state purchased, 200,000 Loss from time of taking to CHAMPIONSHIPS time of batching, 35,000 Nature’s Own Wrapping Keeps Loss from time of hatching to PRACTICALLY A CLEAN SWEEP, WON BY time of planting, 29,000j Tobacco Best Number planted, 242,000 ! These fish were liberated in the | No artificial package— tin, bag, or tin-foil and paper following waters: —can keep tobacco as well as the natural leaf wrapper May 15, Streams and Ponds, Itetevs The results of the United States Revolver Association 1912 Outdoor that holds all the original flavor and moisture in the L itch field, 10,000 j Championships, just officially announced, show that users of Peters Sickle plug. W hen you whittle off a pipeful, you always 22, Cobbosseecontee Cartridges won FIRST in every match but one, also Second place in Lake, Manchester, 15,000 j one match, Third in three matches and fifth in two. get fresh tobacco, that bums slowly, and smokes cool 24, Narrows Pond, Win Match A. Revolver Championship Match D. Military Record and sweet. throp, 5,000 ; 1st—A. M. Poindexter, 467 1st—Dr. J. H. Snook, 212 Match F. Pocket Revolver Championship Chopped-up, “ package” tobacco loses much of its moisture Berry Pond, Win 1st—Dr. O. A. Burgeson, 208 throp, 5,000 | before it goes into the package, and keeps getting drier all the time.