235.SUDIP KUMAR GHOSH.Cdr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

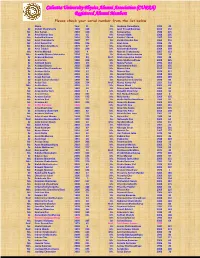

Calcutta University Physics Alumni Association (CUPAA) Registered Alumni Members Please Check Your Serial Number from the List Below Name Year Sl

Calcutta University Physics Alumni Association (CUPAA) Registered Alumni Members Please check your serial number from the list below Name Year Sl. Dr. Joydeep Chowdhury 1993 45 Dr. Abhijit Chakraborty 1990 128 Mr. Jyoti Prasad Banerjee 2010 152 Mr. Abir Sarkar 2010 150 Dr. Kalpana Das 1988 215 Dr. Amal Kumar Das 1991 15 Mr. Kartick Malik 2008 205 Ms. Ambalika Biswas 2010 176 Prof. Kartik C Ghosh 1987 109 Mr. Amit Chakraborty 2007 77 Dr. Kartik Chandra Das 1960 210 Mr. Amit Kumar Pal 2006 136 Dr. Keya Bose 1986 25 Mr. Amit Roy Chowdhury 1979 47 Ms. Keya Chanda 2006 148 Dr. Amit Tribedi 2002 228 Mr. Krishnendu Nandy 2009 209 Ms. Amrita Mandal 2005 4 Mr. Mainak Chakraborty 2007 153 Mrs. Anamika Manna Majumder 2004 95 Dr. Maitree Bhattacharyya 1983 16 Dr. Anasuya Barman 2000 84 Prof. Maitreyee Saha Sarkar 1982 48 Dr. Anima Sen 1968 212 Ms. Mala Mukhopadhyay 2008 225 Dr. Animesh Kuley 2003 29 Dr. Malay Purkait 1992 144 Dr. Anindya Biswas 2002 188 Mr. Manabendra Kuiri 2010 155 Ms. Anindya Roy Chowdhury 2003 63 Mr. Manas Saha 2010 160 Dr. Anirban Guha 2000 57 Dr. Manasi Das 1974 117 Dr. Anirban Saha 2003 51 Dr. Manik Pradhan 1998 129 Dr. Anjan Barman 1990 66 Ms. Manjari Gupta 2006 189 Dr. Anjan Kumar Chandra 1999 98 Dr. Manjusha Sinha (Bera) 1970 89 Dr. Ankan Das 2000 224 Prof. Manoj Kumar Pal 1951 218 Mrs. Ankita Bose 2003 52 Mr. Manoj Marik 2005 81 Dr. Ansuman Lahiri 1982 39 Dr. Manorama Chatterjee 1982 44 Mr. Anup Kumar Bera 2004 3 Mr. -

Dr. Debanjana Dey

DR. DEBANJANA DEY Assistant Professor of Economics Department of Commerce (Evening), St. Xavier's College (Autonomous) 30 Mother Teresa Sarani, Kolkata, West Bengal 700016 Email : [email protected] Academic Qualification: . Ph.D. (Awarded in 2016) under UGC New Regulation in Economics, University of Calcutta; Title : Eco-System Dependent Livelihood and Urban Land-Use Practices: The Challenges for Kolkata and East Kolkata Wetlands . M.Phil (session 2010-2012)in Economics from University of Calcutta. Title : Ecosystem and Livelihood Support: A study on East Kolkata Wetlands . M.Sc. (2009) in Economics from University of Calcutta; . B.Sc. (2007) in Economics Hons. From Bidhannagar College, University of Calcutta; . Higher Secondary (2004) from Bethune Collegiate School (WBCHSE); . Madhyamik (2002) from Ramakrishna Sarada Mission Sister Nivedita Girls’ School (WBBSE); Past Employment: Teaching Experience: . Presently working as ‘Assistant Professor’ of Economics at the Department of Commerce (Evening), St. Xavier's College (Autonomous) since January, 2018; . Worked as ‘Assistant Professor’ of Economics, School of Economics and Commerce, Adamas University, Barasat, West Bengal (August 2016 to January, 2018); Research Experience: . Worked as a ‘Research Assistant’ in Indian Institute of Management, Kolkata (IIMC) (2016); . Worked as ‘Temporary Investigator cum Socio-economic data Collector’ in externally funded project titled ‘Physical Growth, Body Composition Nutritional Status of Bengali school aged children, adolescents and young adults of Calcutta India: Effects of socio- economic factors on secular trends’, sponsored by the ‘Neys Van Hoogstraten Foundation, The Netherlands’ and ‘Indian Statistical Institute, Calcutta’ from August, ISI Kolkata, Biological Anthropological Unit (2010); . Worked as ‘Research Assistant’ in ‘Project on Agrarian Relations in India (PARI)’in Foundation for Agrarian Studies (FAS), Kolkata from 2009-2010; 1 Fellowship: . -

The Annual Quality Assurance Report (AQAR) of the IQAC (For Affiliated/Constituent Colleges)

The Annual Quality Assurance Report (AQAR) of the IQAC (For Affiliated/Constituent Colleges) Institutions Accredited by NAAC need to submit an Annual self-reviewed progress report i.e. Annual Quality Assurance Report (AQAR) to NAAC, through its IQAC. The report is to detail the tangible results achieved in key areas, specifically identified by the IQAC at the beginning of the Academic year. The AQAR period would be the Academic Year.(For example, July 1, 2017 to June 30, 2018) Part – A Data of the Institution (data may be captured from IIQA) 1. Name of the Institution Brahmananda Keshab Chandra College Name of the Head of the institution: Dr. Papia Chakraborti Designation: Principal Does the institution function from own campus: Yes Phone no./Alternate phone no.: 03325772486 Mobile no.: 9830467690 Registered e-mail: [email protected] Alternate e-mail : [email protected] Address :111/2, B.T.Road, Bon-Hooghly City/Town : Kolkata State/UT : West Bengal Pin Code : 700108 2. Institutional status: Affiliated / Constituent: Affiliated Type of Institution: Co-education Location : Urban Financial Status: Grants-in aid/ UGC 2f and 12 (B) Name of the Affiliating University: West Bengal State University Name of the IQAC Co-ordinator : Dr Aparajita Nag Phone no. : 03325772486 Alternate phone no. 03324622590 Brahmananda Keshab Chandra College-AQAR 2018-19 Page 1 Mobile: 9836557985 IQAC e-mail address: [email protected] Alternate Email address: [email protected] 3. Website address: www.bkccollege.org Web-link of the AQAR: (Previous Academic Year): https://www.bkccollege.org/aqar/AQAR2017-18.pdf 4. Whether Academic Calendar prepared during the year? YES if yes, whether it is uploaded in the Institutional website: YES (Academic Calendar of 2018-19 is attached as Annexure 2. -

Counting Arrangements WBLA2021.Xlsx

Counting Venues for General Elections to WBLA, 2021 Counting Name of the Counting Centre AC No. & Name Centre No. WB-1 Mekliganj Higher Secondary School 1-MEKLIGANJ (SC) 2-MATHABHANGA (SC) WB-2 Mathabhanga College 5-SITALKUCHI (SC) 3-COOCH BEHAR UTTAR (SC) WB-3 Cooch Behar Polytechnic 4-COOCH BEHAR DAKSHIN 6-SITAI (SC) WB-4 Dinhata College 7 DINHATA 8 NATABARI WB-5 Tufanganj Mahavidyalaya 9- TUFANGANJ 10-KUMARGRAM (ST) 11-KALCHINI (ST) WB-6 Alipurduar University 12-ALIPURDUAR 13-FALAKATA (SC) 14-MADARIHAT (ST) 15- DHUPGURI (SC) WB-7 NBU 2nd Campus, Science Building 17- JALPAIGURI (SC) WB-8 Netaji Subash Open University 16- MAYNAGURI (SC) 18- RAJGANJ (SC) WB-9 NBU 2nd Campus, Technology Building 19- DABGRAM FULBARI 20- MAL (ST) WB-10 Parimal Mitra Smriti College, Mal 21- NAGRAKATA (ST) The Scottish Universities’ Mission Institution (S.U.M.I.), WB-11 22 - KALIMPONG Kalimpong WB-12 Darjeeling Government College 23-DARJEELING WB-13 St. Alphonsus High School 24-KURSEONG 25-MATIGARA & NAXALBARI (SC) WB-14 Siliguri College 26-SILIGURI 27-PHANSIDEWA (ST) 28- CHOPRA 29- ISLAMPUR WB-15 Islampur College 30-GOALPOKHER 31- CHAKULIA 32-KARANDIGHI 33-HEMTABAD (SC) WB-16 Raiganj Polytechnic 34-KALIAGANJ (SC) 35-RAIGANJ AC 36-ITAHAR AC 37-KUSHMANDI (SC) WB-17 Buniadpur Mahavidyalaya 42-HARIRAMPUR 38-KUMARGANJ 39-BALURGHAT WB-18 Balurghat College 40-TAPAN(ST) 41-GANGARAMPUR(SC) 43-HABIBPUR (ST) 44-GAZOLE (SC) 48-RATUA WB-19 MALDA POLYTECHNIC COLLEGE 49-MANIKCHAK 53-SUJAPUR 54-BAISNABNAGAR Counting Name of the Counting Centre AC No. & Name Centre No. -

Bidhannagar College

Bidhannagar College Kolkata An exclusive Guide by Bidhannagar College Reviews on Placements, Faculty & Facilities Check latest reviews and ratings on placements, faculty, facilities submitted by students & alumni. Reviews (Showing 20 of 26 reviews) Overall Rating (Out of 5) 3.5 Based o n 24 Verif ied Reviews Distribution of Rating >4-5 star 21% >3-4 star 58% >2-3 star 17% 1-2 star 4% Component Ratings (Out of 5) Placements 2.6 Infrastructure 3.6 Faculty & Course 3.7 Curriculum Crowd & Campus Life 3.5 Value for Money 4.3 The Verif ied badge indicates that the reviewer's details have been verified by Shiksha, and reviewers are bona f ide students of this college. These reviews and ratings have been given by students. Shiksha does not endorsed the same. Out of 26 published reviews, 24 reviews are verif ied. Anonymous | B.Sc. (Hons.) in Anthropology - Batch of 2021 Verified Reviewed on 5 Aug 2021 4.2 Placements 2 Infrastructure 4 Faculty & Course Curriculum 5 Crowd & Campus Life 5 I am satisfied with college life. Placements: At the UG level, there are no placements for students. However, people from employment exchange comes to visit our college and conduct a seminar with students. I do not have an idea about the salary packages offered in our college. Companies do not visit our college to hire students. Disclaimer: This PDF is auto-generated based on the information available on Shiksha as on 23-Sep-2021. Infrastructure: The department of Anthropology at Bidhannagar College is one of the best in the entire West Bengal. -

Rituparna Das

RITUPARNA DAS CURRENT AREAS OF WORK Economics, Banking and Finance SUMMARY QUALIFICATION PhD (Money Supply in India), M.Sc.(Economics), B.Sc.(Economics Honours), MBA, NET and State Research Scholarship FULL TIME ACADEMIC EXPERIENCE 14 Years 6 Months CORE COMPETENCIES Since 2012 Mathematical Economics Microeconomics Policy Study Econometrics Microsoft Mathematics XLStat Software Since 2007 Bank Lending Credit Risk for Banks Project Finance Bank Investment Market Risk for Banks Corporate Finance Bank Treasury Bank Asset Liability Managerial Economics Management Management Risk Modelling Financial Functions in Easyfit Software Analysis Tool Pack PROWESS DerivaGem Since 2002-2006 Monetary Economics Macroeconomics Econometrics Eviews Software Best Fit Software Statistical Functions in Analysis Tool Pack CURRENT DESIGNATION, WORKPLACE Designation: Associate Professor (Policy Science) since April 2009; and Executive Director (Centre of Risk Management and Derivatives) since May 2012 ACADEMIC AND PROFESSIONAL QUALIFICATIONS Academic Qualifications # March 2006 Award of Ph.D. Degree * National Law University Jodhpur, (Based on External Examiners’ Recommendations, No marking System) (Faculty of Management Studies) 1 of 10 April 1994 Award of Master of Science Degree in Economics, Calcutta University, July 1991 Award of Bachelor of Science Degree in Economics Honours, Calcutta University December 2000 Passed National Eligibility Test (NET) in Economics for lectureship in universities and colleges of India University Grants Commission December 2000 Passed State Level Eligibility Test (SLET) in Economics for lectureship in universities and colleges of India West Bengal College Service Commission July 1988 Passed Higher Secondary Examination, Marks West Bengal Council of Higher Secondary Examination June 1986 Passed Secondary Examination, Marks West Bengal Board of Secondary Examination #Average score of all examinations is above 60% and from the State of West Bengal, India. -

West Bengal State University, Barasat, 24 PGS (N) Schedule and Seat Allotment for B.Sc

West Bengal State University, Barasat, 24 PGS (N) Schedule and Seat allotment for B.Sc. Part I Practical Examinations, Zoology (Honours) – 2018 Reporting time: 10.45 Examination Centre Paper Date of Candidates allotted (122) Examination BKC College, 111/2 B.T.Road, Paper III 16.07.2018 Barrackpore Rastraguru Surendranath College Batch I (20) Bonhooghly, P.O. – Bonhooghly, (Monday) Kolkata 11 am ROLL NO. REGN. NO. 118212322149 1031721100491 118212322150 1031721400463 118212322151 1031721400490 118212322152 1031721100465 118212322153 1031721400464 118212322154 1031721100498 118212322155 1031721400470 118212322156 1031721100488 118212322157 1031721400508 118212322158 1031721400489 118212322159 1031721400466 118212322160 1031721400492 118212322161 1031721400478 118212322162 1031721400476 118212322163 1031721400497 Page 1 of 34 118212322164 1031721400456 118212322165 1031721100504 118212322166 1031721100474 118212322167 1031721300047 118212322168 1031721200473 BKC College, 111/2 B.T.Road, Paper III 17.07.2018 Barrackpore Rastraguru Surendranath College Batch II (20) Bonhooghly, P.O. – Bonhooghly, (Tuesday) Kolkata 11 am ROLL NO. REGN. NO. 118212322169 1031721400496 118212322170 1031721400505 118212322171 1031721400486 118212322172 1031721400462 118212322173 1031721100499 118212322174 1031721400469 118212322175 1031721400461 118212322176 1031721400460 118212322177 1031721300494 118212322178 1031721400482 118212322179 1031722400506 118212322180 1031721400468 118212322181 1031722300500 118212322182 1031721400495 118212322183 1031721300467 Page -

West Bengal State University B.Sc. Part II Honours

West Bengal State University B.Sc. Part II Honours Practical (PHSA IV B) Examination 2016 in Physics Date: 08/07/2016 - 19/07/2016 Time: 11-00 AM - 5-00 PM Card Drawing at 10-30 AM Note: If the Roll Number of a candidate is missing from the list given below then he/she is required to report on or before 07/07/2013 to the centre where the students of his/her college are allotted to, and the internal examiners of that centre are to accommodate him/her in a convenient date. Centres Examinees from Colleges Date Roll No.s of allotted Candidates Bhairab Ganguly College Bidhannagar College 08/7/2016 216230734072 Feeder Road,Belgharia 216230734073 Kolkata-700056 216130734074 216130734075 216130734076 216130734077 216130734078 216130734079 09/7/2016 216130734080 216130734081 216130734082 216230734083 216130734084 216130734085 216230734086 216130734087 11/7/2016 216130734088 216230734089 216130734090 216130734091 216130734092 216230734093 216130734094 216130734095 12/7/2016 216130734096 216230734097 2C6130765790 2C6130765791 2C6130765792 Gobardanga Hindu College 13/7/2016 216112820849 216112820850 216112820851 216112820852 216112820853 216112820854 216112820855 216112820856 Centres Examinees from Colleges Date Roll No.s of allotted Candidates Bhairab Ganguly College Gobardanga Hindu College 14/7/2016 216112820857 Feeder Road,Belgharia 216112820858 Kolkata-700056 216112820859 216112820860 216213927607 216213927608 2C6112859516 2C6213963221 Mahadevananda Mahavidyalaya 15/7/2016 216213624219 216213624220 216113624221 216113624222 216213624223 216113624224 -

BIDHANNAGAR COLLEGE (NAAC-Accredited With

BIDHANNAGAR COLLEGE (NAAC-accredited with B+) PRINCIPAL: DR. MADHUMITA MANNA, W.B.S.E.S. PROSPECTUS 2018 Address: EB-2, Sector-I, Salt Lake City, Kolkata - 700064 Phone: (033) 23374761 (Office) Fax: +91-(033) 2337 4782 Website: www.bidhannagarcollege.org Email:[email protected] PRINCIPAL’S WELCOME NOTE Welcome to Bidhannagar College, a purely Government Establishment since 1984. It is among the best of the colleges affiliated to the West Bengal State University and is better than most of the colleges under any university in the state of West Bengal, given the diversity of subjects taught and the vibrant modes of learning adopted by the students under the guidance of inspiring teachers / professors. The prospect of new teachers joining the College, especially at every turn of planned development, which the College has just reasons to boast of, adds variety, expertise and commitment to the respective Departments in particular and to the College in general. Of the sixteen Departments, three offer PG Courses –three more likely to be added, subject to final inspection, to the existing three: Anthropology, Botany and Education in addition to Chemistry, Microbiology and Zoology. Still, there are new initiatives in the offing. With no space-crunch, no intellectual potentiality-crunch and no lack of initiative, the College is rich in multi-faceted infrastructure –smart class rooms, regularly enriched laboratories, museums, upgraded gymnasium, to name only a few. All we need is an influx of intelligent and sincere students, who are ready to co-operate with the teachers to get engaged in a vibrant, interactive, teaching-learning process as well as in the co-curricular activities designed for adjustment, tolerance, socialization –an all-round development. -

Barasat Govt. College College College College CHEMISTRY 68 - 43 - MICROBIOLOGY 74 - 58 - ZOOLOGY 67 71 48 58

OF NAAC CYCLE-I ACCREDITATION (2006): “B++” GRADE (CGPA: 2.60) Submitted to National Assessment and Accreditation Council (NAAC) An Autonomous Institution of the University Grants Commission P.O. Box No 1075 Nagarbhavi Bangalore-560072 India BNC SSR 2016 CONTENT CONTENTS Pages Preface i-ii Executive Summary 1-12 SWOC Analysis 13-16 Profile of the College 17-28 CRITERION-WISE INPUTS • Criterion I : Curricular Aspects 29-38 • Criterion II : Teaching-Learning and Evaluation 39-64 • Criterion III : Research, Consultancy and Extension 65-102 • Criterion IV : Infrastructure and Learning Resources 103-125 • Criterion V : Student Support and Progression 126-162 • Criterion VI : Governance, Leadership & Management 163-191 • Criterion VII : Innovations and Best Practices 192-198 Profile of Officer-in-Charge 199-203 EVALUATIVE REPORTS OF THE DEPARTMENTS SCIENCE • Department of Anthropology 204-211 • Department of Botany 212-221 • Department of Chemistry 222-232 • Department of Economics 233-239 • Department of Geography 240-247 • Department of Mathematics 248-256 • Department of Microbiology 257-267 • Department of Physics 268-275 • Department of Statistics 276-283 • Department of Zoology 284-294 ARTS Department of Bengali 295-303 Department of Education 304-313 Department of English 314-321 Department of History 322-328 Department of Philosophy 329-335 Department of Political Science 336-342 Post Accreditation Initiatives 343-349 Annexure -1 a) Department Wise Publication 350-384 Annexure -2 a) Affiliation – Section 12 (B) 385 b) Affiliation – Section 2 (F) 386 c) Certificate of Accreditation of Cycle -1 (2006) 387 Certificate of Declaration 388 BNC SSR 2016 PREFACE PREFACE Bidhannagar College, a well-known co-educational institution, has the rare distinction of offering quality education to students from Kolkata as well as the suburbs, owing to its location on the fringes of the city. -

Rongili Biswas

RONGILI BISWAS Associate Professor of Economics Maulana Azad College, Kolkata India and Associate Researcher in Economics (Honorary) Department of Public Policy and Public Choice (POLIS) University of Eastern Piedmont Italy Personal Details 19/7 Naktala Lane Kolkata-700 047 ADDRESS India FATHER’S Hemango Biswas NAME MOTHER’S NAME Ranu Biswas TELEPHONE Phone : 00919903092249 [email protected] EMAIL [email protected] Associate Professor of Economics CURRENT Maulana Azad College POSITION Kolkata India PLACE OF Calcutta, India BIRTH NATIONALITY Indian 1 Areas of Research Interest Public Economics and Political Economy Jurisdiction formation and wealth stratification Lobbying within a federal structure and resource distribution Fiscal federalism, politics of democracy, politics of redistribution Tax evasion Political bargaining Law and economics Classical political economy/economic history Rural Poverty and Development Economics Trade openness and poverty at the sub-national level in India Rural poverty alleviation programmes: implications for India Education Ph. D (Economics), Jadavpur University, Calcutta, India and Centre for Studies in Social Sciences, Calcutta, India December, 2003. M.Phil.(Economics), Jadavpur University, Calcutta, India, 1993. M.A. (Economics), Jadavpur University, Kolkata, India, 1990. Specialization: Econometrics and International Economics. B.A. (Economics), Jadavpur University, Kolkata, India, 1988. Publications Refereed Journals The segregative properties of endogenous formation of jurisdictions with a welfarist central government (with Nicolas Gravel, Rémy Oddou), Social Choice and Welfare (Wiley-Blackwell) vol. 41(2), 293-319, 2013. Tax Evasion and Self-Protection in a Model with Gatekeepers (with Carla Marchese and Fabio Privileggi), Journal of Economics (Springer), vol. 110, 125- 140, 2013. 2 Fiscal Federalism, State Lobbying and Discretionary Finance: Evidence from India (with Sugata Marjit and Velayoudom Marimotou), Economics and Politics (Wiley-Blackwell), vol. -

Dr. a B H I J I T M a N D a L

Dr. A B H I J I T M A N D A L EDUCATION 10 + 12 – Ramakrishan Mission Vivekananda Veda Vidyalaya Belur Math, Howrah, WB. Sanskrit Medium, 2006 & 2008. B.A – Ramakrishna Mission Vidyamandira, Belur Math, Howrah, WB. Sanskrit Honours, 2011. M.A. - Ramakrishna Mission Vidyamandira, Belur Math, Howrah, WB. Vyakaranam, 2013. Ph. D. – University of Calcutta, Kolkata, WB, 2018. ASSISTANT PROFESSOR TITLE: ŚĀBDIKANAYE ŚĀBDABODHASAHAKĀRIKĀRAṆAVIMARŚAҢ DEPARTMENT OF SANSKRIT Research Interested Area COOCH BEHAR PANCHANAN 1. Paniniyan system of Sanskrit grammar. Specially BARMA UNIVERSITY Śābdabodha (meaningof sentence) and the sub-causes Vivekananda Street, of Śābdabodha, that are Ākānkşā (Syntactic Cooch Behar, w.b. Expectancy), Yogyatā (Logical Consistency), Āsatti India, 736101 (Phonetic Contiguity) and Tātparya. +91 8670935260 2. Linguistic. [email protected] 3. Indian Philosophy. dob – 17 / 11 / 1991 4. Philosophy of Grammar. PUBLICATIONS with ISSN/ISBN 1. Śridurgāstavaԧ, 2011, Vidyamandira Patrika, Ramakrishna Mission Vidyamandira. 2. Śdurgāstutiԧ, 2012, Vidyamandira Patrika, Ramakrishna Mission Vidyamandira. 3. Jātir unnatite dharmer prāsangikatā, 2014, Ātmaśakti, (ISSN - 2321-5062, 2nd year, III & IV Vol.), Viswasevā Sangha, Kolkata. 4. Vāyośabdatvāpatti, 2014, Anvikşā (ISSN- 0587-1646, Vol. XXXVI, Part –I, Refereed Journal), Jadavpur University, Kolkata, WB. 5. Vyākaraṇamukhyproyojonakhandanamandnaṃ, 2015, Sāraswati (ISSN – 2321-9072, Vol. I), Ramakrishna Mission Vidyamandira, Belur Math, Howrah, WB. 6. Boudharthasya vāchatwanirūpaṇṃ, 2015, Lalita (ISSN- 0975- 6256, Vol. VII) Kishor Vidya Niketan, Benaras, UP. Dr. A B H I J I T M A N D A L, Assistant Professor of Sanskrit, CBPBU 7. Vartamānepi sanskritaṃ śikhareśikhrāyitaṃ, 2015, Ādhunikasamāje sanskritasyopjogitā’ (ISBN – 978-93-81795-71-2, July), All Bengal Sanskrit Lover’s Association, Burdwan. 8. Yogyatāyāԧ śābdavodhasahakārikāraṇavimarśaԧ, 2016, Anvikşā (ISSN- 0587-1646, Vol.