UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

El Paso and the Twelve Travelers

Monumental Discourses: Sculpting Juan de Oñate from the Collected Memories of the American Southwest Inaugural-Dissertation zur Erlangung der Doktorwürde der Philosophischen Fakultät IV – Sprach- und Literaturwissenschaften – der Universität Regensburg wieder vorgelegt von Juliane Schwarz-Bierschenk aus Freudenstadt Freiburg, Juni 2014 Erstgutachter: Prof. Dr. Udo Hebel Zweitgutachter: Prof. Dr. Volker Depkat CONTENTS PROLOGUE I PROSPECT 2 II CONCEPTS FOR READING THE SOUTHWEST: MEMORY, SPATIALITY, SIGNIFICATION 7 II.1 CULTURE: TIME (MEMORY) 8 II.1.1 MEMORY IN AMERICAN STUDIES 9 II.2 CULTURE: SPATIALITY (LANDSCAPE) 13 II.2.1 SPATIALITY IN AMERICAN STUDIES 14 II.3 CULTURE: SIGNIFICATION (LANDSCAPE AS TEXT) 16 II.4 CONCEPTUAL CONVERGENCE: THE SPATIAL TURN 18 III.1 UNITS OF INVESTIGATION: PLACE – SPACE – LANDSCAPE III.1.1 PLACE 21 III.1.2 SPACE 22 III.1.3 LANDSCAPE 23 III.2 EMPLACEMENT AND EMPLOTMENT 25 III.3 UNITS OF INVESTIGATION: SITE – MONUMENT – LANDSCAPE III.3.1 SITES OF MEMORY 27 III.3.2 MONUMENTS 30 III.3.3 LANDSCAPES OF MEMORY 32 IV SPATIALIZING AMERICAN MEMORIES: FRONTIERS, BORDERS, BORDERLANDS 34 IV.1 LANDSCAPES OF MEMORY I: THE LAND OF ENCHANTMENT 39 IV.1.1 THE TRI-ETHNIC MYTH 41 IV.2 LANDSCAPES OF MEMORY II: HOMELANDS 43 IV.2.1 HISPANO HOMELAND 44 IV.2.2 CHICANO AZTLÁN 46 IV.3 LANDSCAPES OF MEMORY III: BORDER-LANDS 48 V FROM THE SOUTHWEST TO THE BORDERLANDS: LANDSCAPES OF AMERICAN MEMORIES 52 MONOLOGUE: EL PASO AND THE TWELVE TRAVELERS 57 I COMING TO TERMS WITH EL PASO 60 I.1 PLANNING ‘THE CITY OF THE NEW OLD WEST’ 61 I.2 FOUNDATIONAL -

Style Sheet for Aztlán: a Journal of Chicano Studies

Style Sheet for Aztlán: A Journal of Chicano Studies Articles submitted to Aztlán are accepted with the understanding that the author will agree to all style changes made by the copyeditor unless the changes drastically alter the author’s meaning. This style sheet is intended for use with articles written in English. Much of it also applies to those written in Spanish, but authors planning to submit Spanish-language texts should check with the editors for special instructions. 1. Reference Books Aztlán bases its style on the Chicago Manual of Style, 15th edition, with some modifications. Spelling follows Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary, 11th edition. This sheet provides a guide to a number of style questions that come up frequently in Aztlán. 2. Titles and Subheads 2a. Article titles No endnotes are allowed on titles. Acknowledgments, information about the title or epigraph, or other general information about an article should go in an unnumbered note at the beginning of the endnotes (see section 12). 2b. Subheads Topical subheads should be used to break up the text at logical points. In general, Aztlán does not use more than two levels of subheads. Most articles have only one level. Authors should make the hierarchy of subheads clear by using large, bold, and/or italic type to differentiate levels of subheads. For example, level-1 and level-2 subheads might look like this: Ethnocentrism and Imperialism in the Imperial Valley Social and Spatial Marginalization of Latinos Do not set subheads in all caps. Do not number subheads. No endnotes are allowed on subheads. -

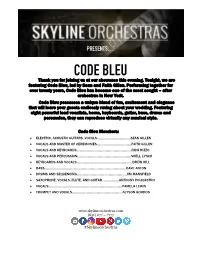

CODE BLEU Thank You for Joining Us at Our Showcase This Evening

PRESENTS… CODE BLEU Thank you for joining us at our showcase this evening. Tonight, we are featuring Code Bleu, led by Sean and Faith Gillen. Performing together for over twenty years, Code Bleu has become one of the most sought – after orchestras in New York. Code Bleu possesses a unique blend of fun, excitement and elegance that will leave your guests endlessly raving about your wedding. Featuring eight powerful lead vocalists, horns, keyboards, guitar, bass, drums and percussion, they can reproduce virtually any musical style. Code Bleu Members: • ELECTRIC, ACOUSTIC GUITARS, VOCALS………………………..………SEAN GILLEN • VOCALS AND MASTER OF CEREMONIES……..………………………….FAITH GILLEN • VOCALS AND KEYBOARDS..…………………………….……………………..RICH RIZZO • VOCALS AND PERCUSSION…………………………………......................SHELL LYNCH • KEYBOARDS AND VOCALS………………………………………..………….…DREW HILL • BASS……………………………………………………………………….….......DAVE ANTON • DRUMS AND SEQUENCING………………………………………………..JIM MANSFIELD • SAXOPHONE, VOCALS, FLUTE, AND GUITAR….……………ANTHONY POLICASTRO • VOCALS………………………………………………………………….…….PAMELA LEWIS • TRUMPET AND VOCALS……………….…………….………………….ALYSON GORDON www.skylineorchestras.com (631) 277 – 7777 #Skylineorchestras DANCE : BURNING DOWN THE HOUSE – Talking Heads BUST A MOVE – Young MC A GOOD NIGHT – John Legend CAKE BY THE OCEAN – DNCE A LITTLE LESS CONVERSATION – Elvis CALL ME MAYBE – Carly Rae Jepsen A LITTLE PARTY NEVER KILLED NOBODY – Fergie CAN’T FEEL MY FACE – The Weekend A LITTLE RESPECT – Erasure CAN’T GET ENOUGH OF YOUR LOVE – Barry White A PIRATE LOOKS AT 40 – Jimmy Buffet CAN’T GET YOU OUT OF MY HEAD – Kylie Minogue ABC – Jackson Five CAN’T HOLD US – Macklemore & Ryan Lewis ACCIDENTALLY IN LOVE – Counting Crows CAN’T HURRY LOVE – Supremes ACHY BREAKY HEART – Billy Ray Cyrus CAN’T STOP THE FEELING – Justin Timberlake ADDICTED TO YOU – Avicii CAR WASH – Rose Royce AEROPLANE – Red Hot Chili Peppers CASTLES IN THE SKY – Ian Van Dahl AIN’T IT FUN – Paramore CHEAP THRILLS – Sia feat. -

Art. Music. Games. Life. 16 09

ART. MUSIC. GAMES. LIFE. 16 09 03 Editor’s Letter 27 04 Disposed Media Gaming 06 Wishlist 07 BigLime 08 Freeware 09 Sonic Retrospective 10 Alexander Brandon 12 Deus Ex: Invisible War 20 14 Game Reviews Music 16 Kylie Showgirl Tour 18 Kylie Retrospective 20 Varsity Drag 22 Good/Bad: Radio 1 23 Doormat 25 Music Reviews Film & TV 32 27 Dexter 29 Film Reviews Comics 31 Death Of Captain Marvel 32 Blankets 34 Comic Reviews Gallery 36 Andrew Campbell 37 Matthew Plater 38 Laura Copeland 39 Next Issue… Publisher/Production Editor Tim Cheesman Editor Dan Thornton Deputy Editor Ian Moreno-Melgar Art Editor Andrew Campbell Sub Editor/Designer Rachel Wild Contributors Keith Andrew/Dan Gassis/Adam Parker/James Hamilton/Paul Blakeley/Andrew Revell Illustrators James Downing/Laura Copeland Cover Art Matthew Plater [© Disposable Media 2007. // All images and characters are retained by original company holding.] dm6/editor’s letter as some bloke once mumbled. “The times, they are You may have spotted a new name at the bottom of this a-changing” column, as I’ve stepped into the hefty shoes and legacy of former Editor Andrew Revell. But luckily, fans of ‘Rev’ will be happy to know he’s still contributing his prosaic genius, and now he actually gets time to sleep in between issues. If my undeserved promotion wasn’t enough, we’re also happy to announce a new bi-monthly schedule for DM. Natural disasters and Acts of God not withstanding. And if that isn’t enough to rock you to the very foundations of your soul, we’re also putting the finishing touches to a newDisposable Media website. -

Portable Housing for Mexican Migrant Workers

Copyright Warning & Restrictions The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Under certain conditions specified in the law, libraries and archives are authorized to furnish a photocopy or other reproduction. One of these specified conditions is that the photocopy or reproduction is not to be “used for any purpose other than private study, scholarship, or research.” If a, user makes a request for, or later uses, a photocopy or reproduction for purposes in excess of “fair use” that user may be liable for copyright infringement, This institution reserves the right to refuse to accept a copying order if, in its judgment, fulfillment of the order would involve violation of copyright law. Please Note: The author retains the copyright while the New Jersey Institute of Technology reserves the right to distribute this thesis or dissertation Printing note: If you do not wish to print this page, then select “Pages from: first page # to: last page #” on the print dialog screen The Van Houten library has removed some of the personal information and all signatures from the approval page and biographical sketches of theses and dissertations in order to protect the identity of NJIT graduates and faculty. ABSTRACT PORTABLE HOUSING FOR MEXICAN MIGRANT WORKERS by Janet Corzo A capable migrant labor force is critical in sustaining the United States' agriculture industry. Yet, migrant farm workers are among the most economically disadvantaged people in the United States (NCFH). The housing available to migrant workers in the United States is typically substandard and subject to other factors, such as local availability, social stigmas and legal status. -

La Onda Bajita: Lowriding in the Borderlands

La Onda Bajita: Lowriding in the Borderlands Michael C. Stone The term "lowriders" refers to automobiles magazine, together with the music of bands like that have been lowered to within a few inches of War, and the Luis Valdez film, Zoot Suit, evoked the road in the expressive style of la onda bajita, images of social and material realities of barrio "the low wave," or "the low trend." It also refers life in shaping and broadcasting the bajito identi to the people who craft them and to those who ty and style. As a public forum on Mexican-Amer own, drive or ride in them. On both sides of the ican identity, Low Rider magazine recast pejora U.S.-Mexico border and throughout the greater tive stereotypes - the culturally ambiguous Southwest, lowriders and their elaborately craft pocho-pachuco (Paredes 1978; Valdez 1978; Vil ed carritos, carruchas, or ranjlas- other names lareal 1959), the dapper zoot-suiter (Mazon for their vehicles- contribute their particular 1984), the street-wise cholo homeboy, the pinto or style to the rich discourse of regional Mexican prison veterano, and the wild vato loco Qohansen American identities. Paradoxically expressed in 1978) -as affirmative cultural archetypes automotive design, lowriders' sense of regional emerging from the long shadow of Anglo domi cultural continuity contributes a distinctive social nation. sensibility to the emergent multicultural mosaic The style apparently arose in northern Cali of late 20th-century North America (Gradante fornia in the late 1930s, but evolved in Los Ange 1982, 1985; Plascencia 1983; Stone 1990). les, where its innovators responded to Holly A synthesis of creative imagination and tech wood's aesthetic and commercial demands. -

1998 Acquisitions

1998 Acquisitions PAINTINGS PRINTS Carl Rice Embrey, Shells, 1972. Acrylic on panel, 47 7/8 x 71 7/8 in. Albert Belleroche, Rêverie, 1903. Lithograph, image 13 3/4 x Museum purchase with funds from Charline and Red McCombs, 17 1/4 in. Museum purchase, 1998.5. 1998.3. Henry Caro-Delvaille, Maternité, ca.1905. Lithograph, Ernest Lawson, Harbor in Winter, ca. 1908. Oil on canvas, image 22 x 17 1/4 in. Museum purchase, 1998.6. 24 1/4 x 29 1/2 in. Bequest of Gloria and Dan Oppenheimer, Honoré Daumier, Ne vous y frottez pas (Don’t Meddle With It), 1834. 1998.10. Lithograph, image 13 1/4 x 17 3/4 in. Museum purchase in memory Bill Reily, Variations on a Xuande Bowl, 1959. Oil on canvas, of Alexander J. Oppenheimer, 1998.23. 70 1/2 x 54 in. Gift of Maryanne MacGuarin Leeper in memory of Marsden Hartley, Apples in a Basket, 1923. Lithograph, image Blanche and John Palmer Leeper, 1998.21. 13 1/2 x 18 1/2 in. Museum purchase in memory of Alexander J. Kent Rush, Untitled, 1978. Collage with acrylic, charcoal, and Oppenheimer, 1998.24. graphite on panel, 67 x 48 in. Gift of Jane and Arthur Stieren, Maximilian Kurzweil, Der Polster (The Pillow), ca.1903. 1998.9. Woodcut, image 11 1/4 x 10 1/4 in. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Frederic J. SCULPTURE Oppenheimer in memory of Alexander J. Oppenheimer, 1998.4. Pierre-Jean David d’Angers, Philopoemen, 1837. Gilded bronze, Louis LeGrand, The End, ca.1887. Two etching and aquatints, 19 in. -

Norma Corral Papers, 1970-2010 CSRC.0135

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8dj5n49 No online items Finding Aid for the Norma Corral Papers, 1970-2010 CSRC.0135 Processed by Irene Truong. Chicano Studies Research Center Library 2016 144 Haines Hall Box 951544 Los Angeles, California 90095-1544 [email protected] URL: http://chicano.ucla.edu Finding Aid for the Norma Corral CSRC.0135 1 Papers, 1970-2010 CSRC.0135 Language of Material: English Contributing Institution: Chicano Studies Research Center Library Title: Norma Corral Papers Creator: Corral, Norma Identifier/Call Number: CSRC.0135 Physical Description: 2.4 linear feet(1 box; 1 record storage carton; 1 oversize box) Date (inclusive): 1970-2010 Abstract: Norma Corral was a UCLA librarian who served on the Faculty Advisory Committee for the Chicano Studies Research Center. The collection includes material related to librarianship in the Latina/o community. Language of Material: Material is in English, Spanish, and Japanese. COLLECTION STORED OFF-SITE AT SRLF: Advance notice required for access. Contact the UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center Library and Archive for paging information. Access Open for research. Arrangement The material is in the order determined by the initial archivist. Biographical / Historical Norma Corral was a UCLA librarian who served on the Faculty Advisory Committee for the Chicano Studies Research Center. In 2001 she was named LAUC-LA Librarian of the Year by her colleagues. Preferred Citation [Identification of item], Norma Corral Papers, 135, UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center, University of California, Los Angeles. Processing Information The collection was processed by Irene Truong. Machine readable finding aid prepared and edited by Doug Johnson, July 2018. -

Latino Rap – Part 2

Latino Rap – Part 2 Intro/History As we discussed last time, many Chicano/Latino rappers do have a gang background (see my prior article on "Chicano Music: An Influence on Gang Violence and Culture”. At one time was on the NAGIA http://www.nagia.org/latino_rap.htm) Sgt. Ron Stallworth of the Utah Dept. of Public Safety has written four books on the subject of gangster rap and even testified at a capital homicide trial in Texas in which rap lyrics were the subject of the case in point. Law Enforcement around the country has become more and more concerned each year with the rap industry’s growing influence on gangs and crime. Det. Wayne Caffey of LAPD has also documented gang ties to many of these gangster rap groups. Rap is part of the Hip-Hop culture that started on the East Coast in the mid-seventies with such groups as the Sugar Hill Gang, Curtis Blow, and Grandmaster Flash. It is a diverse music style and one sub-group could be classified as "Gangster Rappers". Chicano/Latino MC’s may rap in English, Spanish, or Nahualt, or whatever. Increasingly, non-Latino artists are mixing Spanish lyrics in their music in an effort to reach out to the growing Latino market. Latinos have always been a part of the Hip-Hop scene. Early on, in New York, hip-hop break dancers like the Rock Steady Crew and "graffiti artist piecers" like Fidel Rodriquez were involved in the scene. But Latino MC’s did not enjoy that much success at first. -

“Outlaw Pete”: Bruce Springsteen and the Dream-Work of Cosmic American Music

“Outlaw Pete”: Bruce Springsteen and the Dream-Work of Cosmic American Music Peter J. Fields Midwestern State University Abstract During the 2006 Seeger Sessions tour, Springsteen shared his deep identification with the internal struggle implied by old spirituals like “Jacob’s Ladder.” While the Magic album seemed to veer wide of the Seeger Sessions ethos, Working on a Dream re-engages mythically with what Greil Marcus would call “old, weird America” and Gram Parsons deemed “cosmic American music.” Working suggests the universe operates according to “cosmic” principles of justice, judgment, and salvation, but is best understood from the standpoint of what Freud would call “dream work” and “dream thoughts.” As unfolded in Frank Caruso’s illustrations for the picturebook alter ego of Working‘s “Outlaw Pete,” these dynamics may allude to Springsteen’s conflicted relationship with his father. The occasion of the publication in December 2014 of a picturebook version of Bruce Springsteen’s “Outlaw Pete,” the first and longest song on the album Working on a Dream (2009), offers Springsteen scholars and fans alike a good reason to revisit material that, as biographer Peter Ames Carlin remarks, failed in the spring American tour of that year to “light up the arenas.”1 When the Working on a Dream tour opened in April 2009 in San Jose, at least Copyright © Peter Fields, 2016. I want to express my deep gratitude to Irwin Streight who read the 50 page version of this essay over a year ago. He has seen every new draft and provided close readings and valuable feedback. I also want to thank Roxanne Harde and Jonathan Cohen for their steady patience with this project, as well as two reviewers for their comments. -

Songs of the Mormons and Songs of the West AFS L 30

Recording Laboratory AFS L30 Songs of the Mormons and Songs of the West From the Archive of Folk Song Edited by Duncan Emrich Library of Congress Washington 1952 PREFACE SONGS OF THE MORMONS (A side) The traditional Mormon songs on the A side of the length and breadth of Utah , gathering a large this record are secular and historical, and should be collection of songs of which those on this record are considered wholly in that light. They go back in representative. In addition to their work in Utah, time seventy-five and a hundred years to the very they also retraced the entire Mormon route from earliest days of settlement and pioneering, and are upper New York State across the country to Nau· for the opening of Utah and the West extraordi voo and thence to Utah itself, and , beyond that , narily unique documents. As items of general visited and travelled in the western Mormon areas Americana alone they are extremely rare, but when we also consider that they relate to a single group of adjacent to Utah. On all these trips, their chief pur people and to the final establishment of a single pose was the collection of traditional material relat· State, their importance is still further enhanced_ The ing to the early life and history of the Mormons, reason for this lies, not alone in their intrinsic worth including not only songs, but legends, tales, anec as historical documents for Utah, but also because dotes, customs, and early practices of the Mormons songs of this nature, dealing with ea rly pioneering as well. -

Representation of 1980S Cold War Culture and Politics in Popular Music in the West Alex Robbins

University of Portland Pilot Scholars History Undergraduate Publications and History Presentations 12-2017 Time Will Crawl: Representation of 1980s Cold War Culture and Politics in Popular Music in the West Alex Robbins Follow this and additional works at: https://pilotscholars.up.edu/hst_studpubs Part of the European History Commons, Music Commons, Political History Commons, and the United States History Commons Citation: Pilot Scholars Version (Modified MLA Style) Robbins, Alex, "Time Will Crawl: Representation of 1980s Cold War Culture and Politics in Popular Music in the West" (2017). History Undergraduate Publications and Presentations. 7. https://pilotscholars.up.edu/hst_studpubs/7 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the History at Pilot Scholars. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Undergraduate Publications and Presentations by an authorized administrator of Pilot Scholars. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Time Will Crawl: Representation of 1980s Cold War Culture and Politics in Popular Music in the West By Alex Robbins Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in History University of Portland December 2017 Robbins 1 The Cold War represented more than a power struggle between East and West and the fear of mutually assured destruction. Not only did people fear the loss of life and limb but the very nature of their existence came into question. While deemed the “cold” war due to the lack of a direct military conflict, battle is not all that constitutes a war. A war of ideas took place. Despite the attempt to eliminate outside influence, both East and West felt the impact of each other’s cultural movements.