Community Acceptance of Affordable Housing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fraud Is Fun Or How a Foreclosure Rescue Scam Changed My Life

Fraud Is Fun or How a Foreclosure Rescue Scam Changed My Life Peter A. Holland We are an association of trial lawyers seeking justice were raised there. Her mother died there. Mary told me that for our clients and for society. As such, we study diligently she earned $50,000 a year, and that the house was mostly paid “how” to try a case. Get the documents. Note the depositions. for – she had over $100,000 in equity in that house. Subpoena the witnesses. Anticipate the objections. Know the Now my stomach is grumbling, but I have to ask: “How judge. Prepare the Opening Statement. did you get into this mess which I cannot get you out of?” But before we can learn “how” to try a client’s case, we Although she was working part time at the time that I met her, should ask the big question: “why?” Specifically, we should previously she was being treated for a very aggressive breast ask at a very deep level: “Why should anyone care about this cancer. Although Mary’s employer was great to her, after her client and this case”? If we cannot articulate the answer this surgery, rehabilitation, chemotherapy and brief relapse, she question, then we can never truly “win” the case. Why we care about a cause can – and should – direct how we try the case. got laid off from work. She fell behind in her mortgage. Getting in touch with the why instead of obsessing on With nowhere to move to, and with the looming the how can restore the creative juices and the passion to your foreclosure sale of the family homestead, Mary turned to a practice. -

Organ Transplant Discrimination Against People with Disabilities Part of the Bioethics and Disability Series

Organ Transplant Discrimination Against People with Disabilities Part of the Bioethics and Disability Series National Council on Disability September 25, 2019 National Council on Disability (NCD) 1331 F Street NW, Suite 850 Washington, DC 20004 Organ Transplant Discrimination Against People with Disabilities: Part of the Bioethics and Disability Series National Council on Disability, September 25, 2019 This report is also available in alternative formats. Please visit the National Council on Disability (NCD) website (www.ncd.gov) or contact NCD to request an alternative format using the following information: [email protected] Email 202-272-2004 Voice 202-272-2022 Fax The views contained in this report do not necessarily represent those of the Administration, as this and all NCD documents are not subject to the A-19 Executive Branch review process. National Council on Disability An independent federal agency making recommendations to the President and Congress to enhance the quality of life for all Americans with disabilities and their families. Letter of Transmittal September 25, 2019 The President The White House Washington, DC 20500 Dear Mr. President, On behalf of the National Council on Disability (NCD), I am pleased to submit Organ Transplants and Discrimination Against People with Disabilities, part of a five-report series on the intersection of disability and bioethics. This report, and the others in the series, focuses on how the historical and continued devaluation of the lives of people with disabilities by the medical community, legislators, researchers, and even health economists, perpetuates unequal access to medical care, including life- saving care. Organ transplants save lives. But for far too long, people with disabilities have been denied organ transplants as a result of unfounded assumptions about their quality of life and misconceptions about their ability to comply with post-operative care. -

Estimating Home Equity Impacts from Rapid, Targeted Residential Demolition in Detroit, MI: Application of a Spatially-Dynamic Data System for Decision Support

Estimating Home Equity Impacts from Rapid, Targeted Residential Demolition in Detroit, MI: Application of a Spatially-Dynamic Data System for Decision Support A Report Produced by Dynamo Metrics, LLC1 July 2015 ABSTRACT In an effort to further the goals of the Motor City Mapping Initiative, investments were made to create a data architecture for a spatially-dynamic decision support system in Detroit, Michigan. The data system that now exists is capable of tracking the time series dynamics of every one of the more than 384,000 parcels in Detroit between January 1st, 2011 and March 31st, 2015 on a quarterly basis (seventeen quarterly time steps for each parcel). To provide a rapidly produced and useful example of the analytic capabilities of the spatially-dynamic data system, it was used to estimate the effect of the in progress, rapidly deployed Hardest Hit Fund (HHF) demolition investment concentrated in selected areas of Detroit between April 1st, 2014 (Q2 2014) and March 31st, 2015 (Q1 2015). This study utilizes causal modeling that incorporates spatially- dynamic econometric methods in the context of a spatio-temporal treatment effects analysis to estimate the impact of the HHF Blight Elimination Program implementation on single-family home values in Detroit. Using the year prior to HHF implementation (Q2 2013 – Q1 2014) as a control for the rapid and targeted HHF implementation (Q2 2014-Q1 2015), findings suggest that home equity increases of up to 13.8%2 exist for single-family homes that sold inside HHF demolition zones (HHF Zones) after the implementation of the HHF Blight Elimination Program. -

Confirmation of Maslow's Hypothesis of Synergy: Developing An

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health Article Confirmation of Maslow’s Hypothesis of Synergy: Developing an Acceptance of Selfishness at the Workplace Scale Jiro Takaki 1,*, Toshiyo Taniguchi 2 and Yasuhito Fujii 2 1 Department of Public Health, Sanyo Gakuen University Graduate School of Nursing, 1-14-1 Hirai, Naka-ku, Okayama-shi, Okayama 703-8507, Japan 2 Department of Welfare System and Health Science, Okayama Prefectural University, 111 Kuboki, Soja-shi, Okayama 719-1197, Japan; [email protected] (T.T.); [email protected] (Y.F.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +81-86-272-6254 Academic Editor: Paul B. Tchounwou Received: 25 February 2016; Accepted: 28 April 2016; Published: 30 April 2016 Abstract: This study aimed to develop a new Acceptance of Selfishness at the Workplace Scale (ASWS) and to confirm Maslow’s hypothesis of synergy: if both a sense of contribution and acceptance of selfishness at the workplace are high, workers are psychologically healthy. In a cross-sectional study with employees of three Japanese companies, 656 workers answered a self-administered questionnaire on paper completely (response rate = 66.8%). Each questionnaire was submitted to us in a sealed envelope and analyzed. The ASWS indicated high internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.86). Significant (p < 0.001) positive moderate correlations between ASWS scores and job control scores support the ASWS’s convergent and discriminant validity. Significant (p < 0.001) associations of ASWS scores with psychological distress and work engagement supported the ASWS’s criterion validity. In short, ASWS was a psychometrically satisfactory measure. -

2003 Annual Housing Activities Report

Opening Doors for America’s Families Freddie Mac’s Annual Housing Activities Report for 2003 March 15, 2004 Freddie Mac’s Annual Housing Activities Report March 15, 2004 Page 1 About this Report Freddie Mac provides this report to the Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs of the Senate, the Committee on Financial Services of the House of Representatives and the Secretary of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), in fulfillment of the Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corporation Act (“the Freddie Mac Act”)1 and regulations issued by HUD (“the Final Rule”).2 This report describes Freddie Mac’s central role in the housing finance system and housing finance activities in 2003, including information Freddie Mac is required to report under the Freddie Mac Act and the Final Rule.3 This report provides a comprehensive picture of Freddie Mac’s secondary mortgage market activities and the benefits we provide to the housing finance system and to America’s homeowners and renters. Although 2003 was a challenging year for Freddie Mac in many respects, our service to the homeowners and the housing finance system was stronger than ever. Our mortgage purchases enabled millions of families to obtain low-cost mortgages, strengthened the housing market and helped bolster the national economy. We met all of the housing goals and reinforced our strong commitment to increasing minority homeownership with new initiatives in support of the President’s goal. Freddie Mac is proud of the role we play in making the world’s best housing finance system even better for America’s families. 1 12 U.S.C. -

The Detroit Housing Market Challenges and Innovations for a Path Forward

POLICYADVISORY GROUP RESEARCH REPORT The Detroit Housing Market Challenges and Innovations for a Path Forward Erika C. Poethig Joseph Schilling Laurie Goodman Bing Bai James Gastner Rolf Pendall Sameera Fazili March 2017 ABOUT THE URBAN INSTITUTE The nonprofit Urban Institute is dedicated to elevating the debate on social and economic policy. For nearly five decades, Urban scholars have conducted research and offered evidence-based solutions that improve lives and strengthen communities across a rapidly urbanizing world. Their objective research helps expand opportunities for all, reduce hardship among the most vulnerable, and strengthen the effectiveness of the public sector. Copyright © March 2017. Urban Institute. Permission is granted for reproduction of this file, with attribution to the Urban Institute. Cover image by Tim Meko. Contents Acknowledgments iv Sustaining a Healthy Housing Market 1 Demand 1 Supply 10 Credit Access 23 What’s Next? 31 Innovations for a Path Forward 32 Foreclosed Inventory Repositioning 34 Home Equity Protection 38 Land Bank Programs 40 Lease-Purchase Agreements 47 Shared Equity Homeownership 51 Targeted Mortgage Loan Products 55 Rental Housing Preservation 59 Targeting Resources 60 Capacity 62 Translating Ideas into Action 64 Core Principles for Supporting Housing Policies and Programs in Detroit 64 A Call for a Collaborative Forum on Housing: The Detroit Housing Compact 66 Notes 70 References 74 The Urban Institute's Collaboration with JPMorgan Chase 76 Statement of Independence 77 Acknowledgments This report was funded by a grant from JPMorgan Chase. We are grateful to them and to all our funders, who make it possible for Urban to advance its mission. The views expressed are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the Urban Institute, its trustees, or its funders. -

Regulating Home Equity Protection Companies and Contracts: Are States Making “The Best” an Enemy of “The Good”?

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Connecticut Insurance Law Journal School of Law 2016 Regulating Home Equity Protection Companies and Contracts: Are States Making “the Best” an Enemy of “the Good”? John E. Marthinsen Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/cilj Part of the Insurance Law Commons Recommended Citation Marthinsen, John E., "Regulating Home Equity Protection Companies and Contracts: Are States Making “the Best” an Enemy of “the Good”?" (2016). Connecticut Insurance Law Journal. 153. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/cilj/153 REGULATING HOME EQUITY PROTECTION COMPANIES AND CONTRACTS: ARE STATES MAKING “THE BEST” AN ENEMY OF “THE GOOD?” JOHN E. MARTHINSEN* *** Residential homes are the largest, most leveraged assets in most U.S. families’ portfolios. Home equity protection (HEP) contracts offer opportunities to safeguard these real estate interests. In the United States, each state decides if a HEP contract is financial guarantee insurance (FGI) and, therefore, regulated by the state laws and insurance commission rules, or non-insurance financial protection (NIFP), which may escape state and federal regulations. Because HEP contracts have the potential to provide substantial benefits to homeowners, their regulation should be designed to protect state residents and encourage the development of safe alternatives. This article explains HEP contracts, their development, and why states should treat those that require material interests as FGI. Particular focus is put on: (1) the advantages and disadvantages of HEP contracts that are linked to home price indices, (2) why linking these contracts to price indices should not disqualify them as FGI, and (3) how HEP companies engage in regulatory arbitrage by linking their policies to home price indices and claiming NIFP status. -

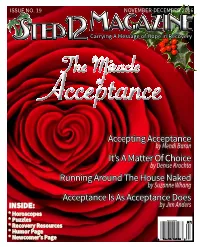

Accepting Acceptance It's a Matter of Choice Running Around the House

ISSUE NO. 19 NOVEMBER-DECEMBER 2016 MagazineTM Ste[p12 Carrying A Message of Hope in Recovery The Miracle Acceptanceof Accepting Acceptance by Mendi Baron It’s A Matter Of Choice by Denise Krochta Running Around The House Naked by Suzanne Whang Acceptance Is As Acceptance Does INSIDE: by Jim Anders * Horoscopes * Puzzles * Recovery Resources * Humor Page * Newcomer’s Page Experience, Strength, and Hope For People Struggling with Food Obsession Accepting the Challenge Q: Since we can’t abstain from eating, how does someone some losses. Eventually the accolades and congratulations will accept ideas of flexibility with food plans? diminish. Your old and new friends will just start expecting you A: The most common threads are honesty and accountability. to be in your new body. Sometimes that will feel like loss and In early recovery, we struggle to accept that the smaller abandonment. If not addressed and accepted, this could result portions we are expected to eat will sustain us—they seem so in regaining lost weight. Men who are accustomed to having a much less than we think are adequate. The rigid food plans commanding larger presence have to accept fitting in with the recommended in treatment centers omit most sugars and refined crowd in a normal body. They need to seek an internal power carbohydrates. Initially, this kind of eating is recommended in which is actually what true recovery is all about. order to get the Newcomer’s attention. When we go through Q: How did you adjust to your new body image? the process of weighing and measuring our healthy portions, A: We are often so accustomed to seeing a certain image in we see how much excess we had been previously consuming. -

GLOSSARY Acceptance House: It Is a Financial Institution That

GLOSSARY Acceptance house: It is a financial institution that ‘accepts; a commercial bill, thereby providing a guarantee about the credit-worthiness of the drawer of the bill. This guaranteeing service is provided against a commission. Bank rate: It is a rate at which the Central Bank of a country rediscounts a bill already discounted by a commercial bank. To put it simply, it is the rate at which the Central Bank provides funds to the commercial banking sector at their time of liquidity problems. Base money: See Reserve money Bill discounting: When a drawer of a commercial bill (which has been accepted by a drawee) is in need of funds, it can sell the bill to a discounting agent at a discount to its face value. The difference between the face value and the discounted value is the income of the discounting agent. Bonds: It is a debt instrument that carries with it the promise to repay the loan on a specific maturity date. A bond is a secured instrument, but may not always directly offer an interest return. In case of some bonds, it is issued at a discount to the maturity value, so that the lender gets some return (also see floating rate bonds, deep discount bonds, indexed bonds and junk bonds). Book building process: It is a method of price discovery in the primary capital market. When the price of an issue is discovered on the basis of demand received from the prospective investors at various price levels, it is called “Book Building process.” Here neither the investor nor the issuer knows the exact price of the issue beforehand. -

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) ADVANCED Workshop Handout

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) ADVANCED Workshop Handout Dr Russell Harris, M.B.B.S, M.A.C. Psych. Med. Phone: 0425 782 055 website: www.actmindfully.com.au e-mail: [email protected] © Russ Harris 2007 This handout consists of: 1. Quick refresher course in ACT pp 2-5 2. 40 tips for getting unstuck with ACT, pp 6- 8 3. Motivation & Resistance, p 9 4. ACT case conceptualisation, p 10 5. Dahl’s 10 Boxes: Values worksheet, p 11 6. Self-as-context, p 12 7. Useful ACT metaphors, pp 13-15 8. ACT with anxiety, pp 15-17 9. ACT with PTSD, pp 18-21 10. Nightmare rehearsal & sleep hygiene handout, pp 22-26 11. Getting unstuck with PTSD, pp 27-30 12. ACT with substance abuse, p 31 13. Forgiveness & compassion scripts (can also use as a client handout), p 32-33 14. Noting or labelling, as a mindfulness skill, p 34 15. Mindful body scan, pp 35-36 16. Loving kindness meditation, pp 37-38 17. Worksheets, pp 39-41 18. ACT with Anger p 42 19. Brief self-as-context exercise p 43 20. Improvising mindfulness p 44 21. Dealing with unhelpful thoughts 45 22. Strosahl’s 3 dimensions: case conceptualization tool 46 © Dr Russ Harris, 2007 [email protected] www.actmindfully.com.au 1 A Quick Refresher: What is Acceptance and Commitment Therapy? Acceptance and Commitment Therapy is an empirically-supported mindfulness- based cognitive-behavioural therapy. ACT has two major goals: • To foster acceptance of unwanted private experiences which are out of personal control • To facilitate commitment and action towards living a valued life Put technically: The goal of ACT is to increase psychological flexibility: the ability to contact the present moment and the psychological reactions it produces, as a fully conscious human being, and based on the situation, to persist with or change behaviour for valued ends Put more simply: The aim of ACT is to create a rich, full and meaningful life, while accepting the pain that inevitably goes with it. -

Preparations for the Eradication of Mice from Gough Island: Results of Bait Acceptance Trials Above Ground and Around Cave Systems

Cuthbert, R.J.; P. Visser, H. Louw, K. Rexer-Huber, G. Parker, and P.G. Ryan. Preparations for the eradication of mice from Gough Island: results of bait acceptance trials above ground and around cave systems Preparations for the eradication of mice from Gough Island: results of bait acceptance trials above ground and around cave systems R. J. Cuthbert1, P. Visser1, H. Louw1, K. Rexer-Huber1, G. Parker1, and P. G. Ryan2 1Royal Society for the Protection of Birds, The Lodge, Sandy, Bedfordshire, SG19 2DL, United Kingdom. <[email protected]>. 2DST/NRF Centre of Excellence at the Percy FitzPatrick Institute, University of Cape Town, Rondebosch 7701, South Africa. Abstract Gough Island, Tristan da Cunha, is a United Kingdom Overseas Territory, supports globally important seabird colonies, has many endemic plant, invertebrate and bird taxa, and is recognised as a World Heritage Site. A key threat to the biodiversity of Gough Island is predation by the introduced house mouse (Mus musculus), as a result of which two bird species are listed as Critically Endangered. Eradicating mice from Gough Island is thus an urgent conservation priority. However, the higher failure rate of mouse versus rat eradications, and smaller size of islands that have been successfully cleared of mice, means that trials on bait acceptance are required to convince funding agencies that an attempted eradication of mice from Gough is likely to succeed. In this study, trials of bait acceptance were undertaken above ground and around cave systems that are potential refuges for mice during an aerial application of bait. Four trials were undertaken during winter, with rhodamine-dyed, non-toxic bait spread by hand at 16 kg/ha over 2.56 ha centred above cave systems in Trials 1-3 and over 20.7 ha and two caves in Trial 4. -

GIFT ACCEPTANCE POLICY Hope House Colorado Is Committed to a Diversified Funding Base, Some of Which May Include Charitable Contributions, to Fulfill Its Mission

GIFT ACCEPTANCE POLICY Hope House Colorado is committed to a diversified funding base, some of which may include charitable contributions, to fulfill its mission. Hope House Colorado, in soliciting or accepting gifts, will maintain and utilize procedures to ensure best practices relative to acceptance and stewardship of gifts, champion communications and acknowledgement. Policy: Our policy is to accept unrestricted gifts and restricted gifts for specific programs or services, that meet the mission of Hope House Colorado, in the form of cash, stocks, deferred or appreciated property. Legal Authority: Tax limitations by local entities, foundations, and individuals often dictate contributions of such goods to a 501(c)(3) organization, and therefore gifts to Hope House Colorado will be directed to the 501(c)(3) entity. Hope House Colorado may seek the advice of legal counsel in matters relating to the acceptance of gifts when appropriate. Examples might include gifts of securities, those involving contracts, or real estate transactions. Purpose: Support the work of Hope House Colorado in its endeavors to lead, serve and strengthen Colorado’s nonprofit sector. Scope: Contributions may be received for all departments and programs of Hope House Colorado as well as to support general operations and capital development. Definition: Gift - Any contribution of cash, equipment, stocks, real property, or in-kind services shall be considered a gift. Acceptance Authority: The Executive Director, Director of Development, and Director of Operations & Expansion have authority to accept all standard cash, publicly traded stock, equipment and in-kind services on behalf of the organization. Any gifts of privately held stock, real estate, other unusual gifts will not be accepted without the approval of the Finance Committee of the Board.