The Word Became Flesh: an Exploratory Essay on Jesus's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Word Made Flesh

1 The Word Made Flesh et’s begin our study of the Gospel of John with what is called the LPrologue, one of the loftiest and most inspiring passages in the New Testament. It lays out the major premise of the Gospel, so it’s a good way to start our exploration. In spite of its weight and importance, the Prologue is actually quite short, consisting of just the first eighteen verses of John. However, because of their weight and importance, we could easily write an entire book just on these verses. Most scholars believe that portions of these first eighteen verses were an early Christian hymn influenced by Greek and Jewish philosophical ideas. John incorporated the hymn, reworking it a bit, because it captured profound ideas about who Jesus is and the meaning of his life. Before delving into the meat of this section, I want to point out what you no doubt have already noticed, that the Gospel begins 15 Copyright © 2015 by Abingdon Press. All rights reserved. 9781501805332_INT_Layout.indd 15 10/20/15 1:12 PM John: The Gospel of Light and Life with these three words: “In the beginning.” You’ll recall that another book of the Bible starts with these same words. Genesis 1:1 starts, “In the beginning. ” John’s use of these words is no accident. He is pointing back to the creation story. For now, I merely want you to notice the reference, and I’ll say more about it at various points throughout the book. The premise of the entire Gospel, so beautifully introduced in the Prologue, is that Jesus embodies God’s Word. -

Responsorial Psalm

CATHOLIC CONVERSATIONS ON THE SCRIPTURES Archdiocese of Miami - Ministry of Christian Formation August 5, 2012 Eighteenth Sunday in Ordinary Time (Cycle B) Gospel reading John 6:24-35 [To be read aloud] When the crowd saw that neither Jesus nor his disciples were there, they themselves got into boats and came to Capernaum looking for Jesus. And when they found him across the sea they said to him, "Rabbi, when did you get here?" Jesus answered them and said, "Amen, amen, I say to you, you are looking for me not because you saw signs but because you ate the loaves and were filled. Do not work for food that perishes but for the food that endures for eternal life, which the Son of Man will give you. For on him the Father, God, has set his seal." So they said to him, "What can we do to accomplish the works of God?" Jesus answered and said to them, "This is the work of God, that you believe in the one he sent." So they said to him, "What sign can you do, that we may see and believe in you? What can you do? Our ancestors ate manna in the desert, as it is written: He gave them bread from heaven to eat.? So Jesus said to them, "Amen, amen, I say to you, it was not Moses who gave the bread from heaven; my Father gives you the true bread from heaven. For the bread of God is that which comes down from heaven and gives life to the world." So they said to him, "Sir, give us this bread always." Jesus said to them, "I am the bread of life; whoever comes to me will never hunger, and whoever believes in me will never thirst." Brief commentary: Although the Fourth Gospel does not include a narrative account of the institution of the Eucharist at the Last Supper, as do the Synoptics and 1 Corinthians, it does offer the most extended reflection on the meaning of the Eucharist in the whole of the New Testament. -

The Real Presence of Christ in Scripture: a Sacramental Approach to the Old Testament

The Real Presence of Christ in Scripture: A Sacramental Approach to the Old Testament by Geoffrey Boyle A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Wycliffe College and Graduate Centre for Theological Studies of the Toronto School of Theology In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Theology awarded by the University of St. Michael's College © Copyright by Geoffrey Boyle 2019 The Real Presence of Christ in Scripture: A Sacramental Approach to the Old Testament Geoffrey Robert Boyle Doctor of Philosophy in Theology University of St. Michael's College 2019 Abstract Of the various sense-making attempts to understand the relation of Christ to the Old Testament over the last century, there is a noticeable absence of any substantial presence. Christ is prophesied, witnessed, predicted, typified, and prefigured; but apart from a few alleged christophanic appearances, he is largely the subject of another, historically subsequent Testament. This thesis surveys the christological approaches to the Old Testament since the early 20th century breach made within historicism, introduces a patristic mindset, proposes an ontological foundation to a sacramental (real-presence) approach, then demonstrates this through a reading of Zechariah 9-14. The goal is to bring together three arenas of study—exegetical, historical, theological—and demonstrate how their united lens clarifies the substantial referent of Scripture, namely Christ. The character of the OT witness is thus presented in christological terms, suggesting a reading that recognizes the divine person within the text itself, at home in the sensus literalis. By way of analogy to the Cyrillian hypostatic union and a Lutheran eucharistic comprehension, the task is to show how one encounters the hypostasis of Christ by means of the text’s literal sense. -

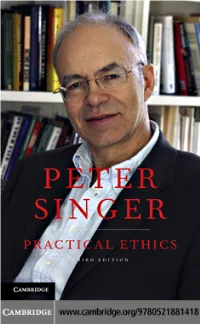

Practical Ethics, Third Edition

This page intentionally left blank Practical Ethics Third Edition For thirty years, Peter Singer’s Practical Ethics has been the classic introduction to applied ethics. For this third edition, the author has revised and updated all the chapters and added a new chapter addressing climate change, one of the most important ethical chal- lenges of our generation. Some of the questions discussed in this book concern our daily lives. Is it ethical to buy luxuries when others do not have enough to eat? Should we buy meat produced from intensively reared animals? Am I doing something wrong if my carbon footprint is above the global average? Other questions confront us as concerned citizens: equality and discrimination on the grounds of race or sex; abortion, the use of embryos for research, and euthanasia; political violence and terrorism; and the preservation of our planet’s environment. This book’s lucid style and provocative arguments make it an ideal text for university courses and for anyone willing to think about how she or he ought to live. Peter Singer is currently Ira W. DeCamp Professor of Bioethics at the University Center for Human Values at Princeton University and Laureate Professor at the Centre for Applied Philosophy and Public Ethics at the University of Melbourne. He is the author or editor of more than forty books, including Animal Liberation (1975), Rethinking Life and Death (1996) and, most recently, The Life You Can Save (2009). In 2005, he was named one of the 100 most influential people in the world by Time magazine. Practical Ethics Third Edition PETER SINGER Princeton University and the University of Melbourne cambridge university press Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, Sao˜ Paulo, Delhi, Dubai, Tokyo, Mexico City Cambridge University Press 32 Avenue of the Americas, New York, ny 10013-2473, usa www.cambridge.org Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9780521707688 C Peter Singer 1980, 1993, 2011 This publication is in copyright. -

The Apostles' Creed the Nicene Creed

4 The Faith We Profess The Apostles’ Creed The Nicene Creed I believe in God, We believe in one God, the Father almighty, the Father, the Almighty, creator of heaven and earth. maker of heaven and earth, of all that is, seen and unseen. I believe in Jesus Christ, his only We believe in one Lord, Jesus Son, our Lord. Christ, the only Son of God, eternally begotten of the Father, God from God, Light from Light, true God from true God, begotten, not made, one in Being with the Father. Through him all things were made. For us men and for our salvation he came down from heaven: He was conceived by the by the power of the Holy Spirit power of the Holy Spirit he was born of the Virgin Mary, and born of the Virgin Mary. and became man. He suffered under Pontius Pilate, For our sake he was crucified was crucified, died, and was buried. under Pontius Pilate; He descended into hell. he suffered, died, and was buried. On the third day he rose again. On the third day he rose again in fulfillment of the Scriptures; He ascended into heaven he ascended into heaven and is seated at the right and is seated at the right hand of the Father. hand of the Father. He will come again to judge the He will come again in glory to living and the dead. judge the living and the dead, and his kingdom will have no end An Introduction to the Apostles’ Creed 5 The Apostles’ Creed The Nicene Creed I believe in the Holy Spirit, We believe in the Holy Spirit, the holy catholic Church, the Lord, the giver of Life, the communion of saints, who proceeds from the the forgiveness of sins, Father and the Son. -

The Nicene Creed: the Niceno- the Apostles’ Creed: Caesarea: Constantinopolitan Creed

Jonathan J. Armstrong, Ph.D. Moody Bible Institute The Creed of Eusebius of The Nicene Creed: The Niceno- The Apostles’ Creed: Caesarea: Constantinopolitan Creed: We believe in one only God, We believe in one God, the We believe in one God, the I believe in God the Father Father almighty, maker of all things Father almighty, creator of things Father almighty, maker of heaven almighty, maker of heaven and earth; visible and invisible; and earth, and of all things visible And in Jesus Christ his only Son visible and invisible; And in one Lord Jesus Christ, the and invisible; our Lord, who was conceived by the And in the Lord Jesus Christ, for he Son of God, the only-begotten of his And in one Lord Jesus Christ, the Holy Ghost, born of the Virgin Mary, is the Word of God, God of God, light Father, of the substance of the only begotten Son of God, begotten of light, life of life, his only Son, the Father, God of God, light of light, of his Father before all worlds, light suffered under Pontius Pilate, was first-born of all creatures, begotten very God of very God, begotten, not of light, very God of very God, crucified, dead, and buried; he of the Father before all time, by made, being of one substance begotten not made, being of one descended into hell; the third day he (ὁμοούσιον) with the Father, by whom also everything was created, substance with the Father, by whom rose again from the dead; he whom all things were made, both all things were made, who for us men who became flesh for our ascended into heaven, and sits on which be in heaven and in earth, who and for our salvation came down the right hand of God the Father redemption, who lived and suffered for us men and for our salvation from heaven and was incarnate by among men, rose again the third day, came down from heaven and was the Holy Ghost and the Virgin Mary, almighty; from thence he shall come returned to the Father, and will come incarnate and was made man. -

Animals Liberation Philosophy and Policy Journal Volume 5, Issue 1

AAnniimmaallss LLiibbeerraattiioonn PPhhiilloossoopphhyy aanndd PPoolliiccyy JJoouurrnnaall VVoolluummee 55,, IIssssuuee 11 -- 22000077 Animal Liberation Philosophy and Policy Journal Volume 5, Issue 1 2007 Edited By: Steven Best, Chief Editor ____________________________________________________________ TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction Steven Best, Chief Editor Pg. 2-3 Introducing Critical Animal Studies Steven Best, Anthony J. Nocella II, Richard Kahn, Carol Gigliotti, and Lisa Kemmerer Pg. 4-5 Extrinsic and Intrinsic Arguments: Strategies for Promoting Animal Rights Katherine Perlo Pg. 6-19 Animal Rights Law: Fundamentalism versus Pragmatism David Sztybel Pg. 20-54 Unmasking the Animal Liberation Front Using Critical Pedagogy: Seeing the ALF for Who They Really Are Anthony J. Nocella II Pg. 55-64 The Animal Enterprise Terrorism Act: New, Improved, and ACLU-Approved Steven Best Pg. 65-81 BOOK REVIEWS _________________ In Defense of Animals: The Second Wave, by Peter Singer ed. (2005) Reviewed by Matthew Calarco Pg. 82-87 Dominion: The Power of Man, the Suffering of Animals, and the Call to Mercy, by Matthew Scully (2003) Reviewed by Lisa Kemmerer Pg. 88-91 Terrorists or Freedom Fighters?: Reflections on the Liberation of Animals, by Steven Best and Anthony J. Nocella, II, eds. (2004) Reviewed by Lauren E. Eastwood Pg. 92 Introduction Welcome to the sixth issue of our journal. You’ll first notice that our journal and site has undergone a name change. The Center on Animal Liberation Affairs is now the Institute for Critical Animal Studies, and the Animal Liberation Philosophy and Policy Journal is now the Journal for Critical Animal Studies. The name changes, decided through discussion among our board members, were prompted by both philosophical and pragmatic motivations. -

Welcome to Our Parish!

Annunciation Catholic Church Altamonte Springs, Florida Mass Intentions for this Weekend Holy Father’s Prayer Intention for August SAT, AUG 18 (Ez 18:1-10, 13b, 30-32/Mt 19:13-15) 8:00 am Jim Vandehey† The Treasure of Families 5:00 pm Michael Rabasca† That any far-reaching decisions of SUN, AUG 19 (Twentieth Sunday in Ordinary Time) economists and politicians may protect 8:00 am Pat Lindenberg† the family as one of the treasures of 10:00 am People of Our Parish Frank Brzezinski† humanity. Joseph Deegan† Bob Muniz† 12:00 pm Paul Higgins Jr.† Mass Schedule 5:30 pm Rob Evans Robinson Jr.† Saturday Vigil: 5pm ¿Habla Español? Mass Intentions for the coming Week Sunday: 8am, 10am, Misa en Español el primer Martes 12pm & 5:30pm* del mes a las 11am. MON, AUG 20 (Ez 24:15-23/Mt 19:16-22) *interpreted for the deaf El grupo de oración contemplativo 7:00 am Mary Hayes† 12:15pm Bob Muniz† le invita a la Misa en Español. Daily Masses LUGAR: En la Iglesia TUE, AUG 21 (Ez 28:1-10/Mt 19:23-30) Monday - Friday: CONTACTO: 407-869-9472 7:00 am Elena Gorricho† 7am & 12:15pm 8:30 am Mae Cunningham Kunz† 12:15 pm Ann Marie Hopkins† Saturday: 8am WED, AUG 22 (Ez 34:1-11/Mt 20:1-16) Portuguese Mass - 11:30 am on Sundays 7:00 am Frances Szafron† Where: Padre Pio’s Place 12:15 pm Irwin Sanders† THU, AUG 23 (Ez 36:23-28/Mt 22:1-14) 7:00 am Anna and Stefan Czarniecki† Eucharistic Adoration 12:15 pm Raymond Shash† Monday, Wednesday and Friday FRI, AUG 24 (Rv 21:9b-14/Jn 1:45-51) from 7:30am - 9pm. -

Illuminating the Darkness: the Naturalistic Evolution of Gothicism in the Nineteenth-Century British Novel and Visual Art

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Dissertations, Theses, and Student Research: Department of English English, Department of 8-2013 Illuminating the Darkness: The Naturalistic Evolution of Gothicism in the Nineteenth-Century British Novel and Visual Art Cameron Dodworth University of Nebraska-Lincoln Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/englishdiss Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Dodworth, Cameron, "Illuminating the Darkness: The Naturalistic Evolution of Gothicism in the Nineteenth- Century British Novel and Visual Art" (2013). Dissertations, Theses, and Student Research: Department of English. 79. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/englishdiss/79 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the English, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Student Research: Department of English by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. ILLUMINATING THE DARKNESS: THE NATURALISTIC EVOLUTION OF GOTHICISM IN THE NINETEENTH- CENTURY BRITISH NOVEL AND VISUAL ART by Cameron Dodworth A DISSERTATION Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Major: English (Nineteenth-Century Studies) Under the Supervision of Professor Laura M. White Lincoln, Nebraska August, 2013 ILLUMINATING THE DARKNESS: THE NATURALISTIC EVOLUTION OF GOTHICISM IN THE NINETEENTH- CENTURY BRITISH NOVEL AND VISUAL ART Cameron Dodworth, Ph.D. University of Nebraska, 2013 Adviser: Laura White The British Gothic novel reached a level of very high popularity in the literary market of the late 1700s and the first two decades of the 1800s, but after that point in time the popularity of these types of publications dipped significantly. -

Text: John 6:51-58 Theme: Digest the Bread of Life We Have Been Making

Text: John 6:51-58 Theme: Digest the Bread of Life We have been making our way through Jesus’ “Bread of Life Discourse” here in John chapter 6 the last couple of weeks. In the event that you have found some of it difficult to understand or difficult to follow, it might make you feel a little better to know that you aren’t alone. While some of your difficulty can certainly be attributed to my limitations as a preacher, even those who heard these verses first hand from Jesus own lips had difficulty, including even Jesus’ disciples who were found grumbling afterwards, “This is a hard teaching, who can accept it?” Still, it is not our goal, nor is it Jesus’ goal for us, to simply walk away from our look at these verses scratching our heads in frustration. Instead it is our goal to strive for understanding of what Jesus says here, to take these words to heart that they may truly feed our souls. It is our goal to Digest the Bread of Life, that He may live in us, and that we may live through Him. It is clear from our text that there were many in the crowd who did not understand what Jesus was saying. They ask the question, “How can this man give us his flesh to eat?” They may as well have simply said, “I don’t get it!” So it is important for our understanding that we answer this question. In order to understand what Jesus is saying, we must take His words in context. -

Legal Research Paper Series

Legal Research Paper Series NON HUMAN ANIMALS AND THE LAW: A BIBLIOGRAPHY OF ANIMAL LAW RESOURCES AT THE STANFORD LAW LIBRARY By Rita K. Lomio and J. Paul Lomio Research Paper No. 6 October 2005 Robert Crown Law Library Crown Quadrangle Stanford, California 94305-8612 NON HUMAN ANIMALS AND THE LAW: A BIBLIOGRPAHY OF ANIMAL LAW RESOURCES AT THE STANFORD LAW LIBRARY I. Books II. Reports III. Law Review Articles IV. Newspaper Articles (including legal newspapers) V. Sound Recordings and Films VI. Web Resources I. Books RESEARCH GUIDES AND BIBLIOGRAPHIES Hoffman, Piper, and the Harvard Student Animal Legal Defense Fund The Guide to Animal Law Resources Hollis, New Hampshire: Puritan Press, 1999 Reference KF 3841 G85 “As law students, we have found that although more resources are available and more people are involved that the case just a few years ago, locating the resource or the person we need in a particular situation remains difficult. The Guide to Animal Law Resources represents our attempt to collect in one place some of the resources a legal professional, law professor or law student might want and have a hard time finding.” Guide includes citations to organizations and internships, animal law court cases, a bibliography, law schools where animal law courses are taught, Internet resources, conferences and lawyers devoted to the cause. The International Institute for Animal Law A Bibliography of Animal Law Resources Chicago, Illinois: The International Institute for Animal Law, 2001 KF 3841 A1 B53 Kistler, John M. Animal Rights: A Subject Guide, Bibliography, and Internet Companion Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 2000 HV 4708 K57 Bibliography divided into six subject areas: Animal Rights: General Works, Animal Natures, Fatal Uses of Animals, Nonfatal Uses of Animals, Animal Populations, and Animal Speculations. -

Toward an Anabaptist Theology of Baptism and Ecclesial Mediation

By One Spirit into One Body: Toward an Anabaptist Theology of Baptism and Ecclesial Mediation By Anthony Gene Siegrist A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Wycliffe College and the Department of Theology of the Toronto School of Theology in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Theology Awarded by Wycliffe College and the University of Toronto © Copyright by Anthony G. Siegrist, 2012 By One Spirit into One Body: Toward an Anabaptist Theology of Baptism and Ecclesial Mediation Anthony Gene Siegrist Doctor of Theology Wycliffe College of the University of Toronto 2012 Abstract The working Anabaptist theology of baptism suffers from a deficient account of divine action, especially as mediated through the church. The goal of this dissertation is to develop resources to remedy this weakness by drawing on elements of the sacramental theology and ecclesiology from the broader, mostly Protestant, tradition. The fact that communities professing to practice believers’ baptism actually baptize children is an important point of departure for this project. This aberration signals underlying confusion about the nature of the church and the relationship of the human and divine actions that form it. A construal of baptism that does not reduce it to rationalist testimony, abstract spiritualism, or the sum of its sociological parts is needed. Such an account can be developed by attending to the ways in which the church embodies the ongoing presence of Christ in the world and exists as a community accompanied by the Spirit through time. In line with this sacramental trajectory believers’ baptism can be understood as a participating witness.