Environmental Infrastructure Inquiry Submission S003 Received 17/08

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MORNINGTON PENINSULA BIODIVERSITY: SURVEY and RESEARCH HIGHLIGHTS Design and Editing: Linda Bester, Universal Ecology Services

MORNINGTON PENINSULA BIODIVERSITY: SURVEY AND RESEARCH HIGHLIGHTS Design and editing: Linda Bester, Universal Ecology Services. General review: Sarah Caulton. Project manager: Garrique Pergl, Mornington Peninsula Shire. Photographs: Matthew Dell, Linda Bester, Malcolm Legg, Arthur Rylah Institute (ARI), Mornington Peninsula Shire, Russell Mawson, Bruce Fuhrer, Save Tootgarook Swamp, and Celine Yap. Maps: Mornington Peninsula Shire, Arthur Rylah Institute (ARI), and Practical Ecology. Further acknowledgements: This report was produced with the assistance and input of a number of ecological consultants, state agencies and Mornington Peninsula Shire community groups. The Shire is grateful to the many people that participated in the consultations and surveys informing this report. Acknowledgement of Country: The Mornington Peninsula Shire acknowledges Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders as the first Australians and recognises that they have a unique relationship with the land and water. The Shire also recognises the Mornington Peninsula is home to the Boonwurrung / Bunurong, members of the Kulin Nation, who have lived here for thousands of years and who have traditional connections and responsibilities to the land on which Council meets. Data sources - This booklet summarises the results of various biodiversity reports conducted for the Mornington Peninsula Shire: • Costen, A. and South, M. (2014) Tootgarook Wetland Ecological Character Description. Mornington Peninsula Shire. • Cook, D. (2013) Flora Survey and Weed Mapping at Tootgarook Swamp Bushland Reserve. Mornington Peninsula Shire. • Dell, M.D. and Bester L.R. (2006) Management and status of Leafy Greenhood (Pterostylis cucullata) populations within Mornington Peninsula Shire. Universal Ecology Services, Victoria. • Legg, M. (2014) Vertebrate fauna assessments of seven Mornington Peninsula Shire reserves located within Tootgarook Wetland. -

Victoria's Hidden Gems

Victoria’s Hidden Gems Delve into the cosmopolitan sophistication and natural beauty of Victoria, journeying past elegant Melbournian arcades, sandstone peaks and the Twelve Apostles that stand imposingly along the spectacular coastline. From trendy cityscapes to quaint villages, scenic coastal drives to white-capped surf, Victoria’s intoxicating charm is revealed on this Inspiring Journey. Their original names: What we now call the Twelve Apostles were originally called The Sow and Piglets. The Sow was Mutton Bird Island, which stands at the mouth of Loch Ard Gorge, and her Piglets were the 12 Apostles. The Twelve Apostles 7 Days Victoria’s Hidden Gems IJVIC Flagstaff Hill Maritime Village Australian Surfing Museum Hepburn Bathhouse & Spa 7 DAYS Melbourne • Daylesford • Dunkeld • The Grampians • Warrnambool • Great Ocean Road • Mornington Peninsula Dunkeld Kitchen Garden Discover The eclectic town of Daylesford, with antique shops, bazaars and cottage industries The iconic Melbourne Cricket Ground Explore Melbourne’s vibrant laneways and arcades Green Olive Farm at Red Hill on the Mornington Peninsula Immerse Visit Creswick Woollen Mills, the last coloured woollen spinning mill in Australia Call in at the high-tech Eureka Centre in Ballarat Experience a Welcome to Country ceremony in the Grampians Browse the Australian National Surfing Museum in Torquay Relax Indulge in a relaxing mineral bath at the historic Hepburn Bathhouse & Spa Melbourne’s shopping arcades On a scenic coastal drive along the Great Ocean Road 7 Days Victoria’s Hidden -

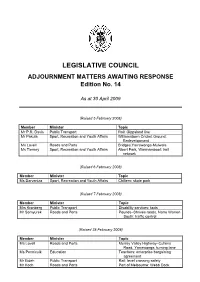

LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ADJOURNMENT MATTERS AWAITING RESPONSE Edition No

LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ADJOURNMENT MATTERS AWAITING RESPONSE Edition No. 14 As at 30 April 2009 (Raised 5 February 2008) Member Minister Topic Mr P.R. Davis Public Transport Rail: Gippsland line Mr Pakula Sport, Recreation and Youth Affairs Williamstown Cricket Ground: Redevelopment Ms Lovell Roads and Ports Bridges:Yarrawonga-Mulwala Ms Tierney Sport, Recreation and Youth Affairs Albert Park, Warrnambool: trail network (Raised 6 February 2008) Member Minister Topic Ms Darveniza Sport, Recreation and Youth Affairs Chiltern: skate park (Raised 7 February 2008) Member Minister Topic Mrs Kronberg Public Transport Disability services: taxis Mr Somyurek Roads and Ports Pounds–Shrives roads, Narre Warren South: traffic control (Raised 28 February 2008) Member Minister Topic Ms Lovell Roads and Ports Murray Valley Highway–Cullens Road, Yarrawonga: turning lane Ms Pennicuik Education Teachers: enterprise bargaining agreement Mr Eideh Public Transport Rail: level crossing safety Mr Koch Roads and Ports Port of Melbourne: Webb Dock 2 Legislative Council Adjournment Matters Awaiting Response Edition No. 14 Mr Elasmar Consumer Affairs Consumer affairs: lottery scams Mr Vogels Rural and Regional Development Bannockburn: community hub Mrs Petrovich Roads and Ports Northern Highway, Kilmore: traffic control (Raised 11 March 2008) Member Minister Topic Ms Tierney Sport, Recreation and Youth Affairs Aireys Inlet tennis club: facilities Mr Vogels Regional and Rural Development Anglesea: riverbank facilities Mr Finn Roads and Ports Sunbury Road, Bulla: traffic -

Legislative Assembly of Victoria

LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY OF VICTORIA VOTES AND PROCEEDINGS Nos 54, 55 and 56 No 54 — Tuesday 18 February 2020 1 The House met according to the adjournment — The Speaker took the Chair, read the Prayer and made an Acknowledgement of Country. 2 QUESTION TIME — (Under Sessional Order 9). 3 LOCAL GOVERNMENT (CASEY CITY COUNCIL) BILL 2020 — Ms Kairouz introduced ‘A Bill for an Act to dismiss the Casey City Council and to provide for a general election for that Council and for other purposes’; and the Bill was read a first time. In accordance with SO 61(3)(b), the House proceeded immediately to the second reading. Ms Kairouz tabled a statement of compatibility in accordance with the Charter of Human Rights and Responsibilities Act 2006. Motion made and question proposed — That this Bill be now read a second time (Ms Kairouz). The second reading speech was incorporated into Hansard. Motion made and question — That the debate be now adjourned (Mr Smith, Kew) — put and agreed to. Ordered — That the debate be adjourned until later this day. 4 NATIONAL ELECTRICITY (VICTORIA) AMENDMENT BILL 2020 — Ms D’Ambrosio introduced ‘A Bill for an Act to amend the National Electricity (Victoria) Act 2005 and the Electricity Industry Act 2000 and for other purposes’; and the Bill was read a first time and ordered to be read a second time tomorrow. 5 DOCUMENTS CITY OF CASEY MUNICIPAL MONITOR REPORT FEBRUARY 2020 — Tabled by leave (Ms Kairouz). Ordered to be published. 288 Legislative Assembly of Victoria SCRUTINY OF ACTS AND REGULATIONS COMMITTEE — Ms Connolly tabled the Alert Digest No 2 of 2020 from the Scrutiny of Acts and Regulations Committee on the: Children, Youth and Families Amendment (Out of Home Care Age) Bill 2020 Crimes Amendment (Manslaughter and Related Offences) Bill 2020 Forests Legislation Amendment (Compliance and Enforcement) Bill 2019 Project Development and Construction Management Amendment Bill 2020 Transport Legislation Amendment Act 2019 (House Amendment) SR No 93 — Road Safety (Traffic Management) Regulations 2019 together with appendices. -

A Social Geography of the Mornington Peninsula (Dr Ian Manning)

A social geography of the Mornington Peninsula (Dr Ian Manning) This article was prepared for the George Hicks Foundation as part of a background paper for a meeting of philanthropists interested in work on the Mornington Peninsula. An evaluation of the costs and benefits of providing educational assistance to disadvantaged families living on the Peninsula is provided in a separate posting. The Mornington Peninsula Shire is known as a place where people can live near the sea, perhaps within walking distance of the beach or on a bluff with a view over the bay, or perhaps among the hills within easy driving distance of the beach. The peninsula faces Port Phillip Bay across a crescent of beaches along which there is a near-continuous strip of urban development, backed by a range of hills which, once over the ridge, slope down to Westernport Bay to the east and Bass Strait to the south. Paradise? Yet not for all residents. As will be shown below, the peninsula has its disadvantaged families, some of them scattered across the shire and some of them concentrated in two main pockets of disadvantage, one centred on Rosebud West and the other on Hastings. Geographically, the peninsula contrasts sharply with the western shore of Port Phillip Bay, where a basalt plain comes down to the sea and separates Melbourne from Geelong. Though similar in distance from Melbourne to the City of Geelong (that is, 60-110 km), the peninsula lacks Geelong’s historic, independent city centre; instead, the peninsula shades from outer suburb to peri-urban; built-up to semi-rural. -

Mornington Peninsula VICTORIA AUSTRALIA

Creating Change Through Education Advance MORNINGTON HASTINGS ROSEBUD Mornington Peninsula VICTORIA AUSTRALIA Advance IMPACT REPORT | 2020 Advance 157 Team $34.8m Members Revenue 944 674 Apprenticeships/ SBAT’s Traineeships 24,502 229,982 Participants Pre-accredited student contact hours 12 1,365,158 Sites Accredited contact hours ADVANCE IMPACT REPORT | 2020 1 “Creating Change Through Education” COMPUTER COURSES FOUNDATION SKILLS CREATING CHANGE THROUGH EDUCATION TRANSPORT CEO/ Principal’s Message BUSINESS AND LOGISTICS COMMUNITY SERVICES To celebrate and acknowledge 40 years of community engagement, I am delighted to HORTICULTURE present the Advance 40th Anniversary Impact Report. HOSPITALITY From a humble beginning, when we opened our More recently in 2016, the establishment of doors on May 26, 1980 Advance has grown from Advance College, a Special Assistance school, having two staff and one site, to a successful, has been a major expansion to our operations. It multi-faceted organisation with three sites and has provided an alternative education setting for more than 35 staff. those young people who would often be at risk of not completing their secondary education. As I reflect on the past four decades I think how fortunate and privileged Advance has been to not Looking back over the last 40 years I can identify only survive but, thrive in the face of many a number of key success factors that have been challenges. We have continued to built resilience critical for our organisation. We have had great and strength underpinned by our founding staff with good governance and strong local philosophy of providing support to those who knowledge. -

Mornington Peninsula (S)

Mornington Peninsula (S) The Mornington Peninsula Shire is located in the Southern Metropolitan region, about 54 km south of Melbourne. Population • Actual and projected population growth are both slightly below the state measures. • People aged 25–44 are under-represented while people aged 65+ are over-represented. Diversity • The percentages of people who were born overseas and who speak a language other than English at home are lower than the state measures. • The rate of new settler arrivals is well below average, with no humanitarian settlers. Disadvantage and social engagement • The percentage of people who feel valued by society is lower than the state measure • The percentages of people who rated their community as a pleasant environment and good or very good for community and support groups are higher than the state measures. • There are a higher than average percentage of people with food insecurity. Housing, transport and education • The percentage of households in rental stress is above the state measure. • There are higher than average percentages of journeys to work which are by car and people with at least 2 hour daily commute. • A higher percentage than average of people did not complete year 12. • The rate of homeless people (estimated) per 1,000 population is lower than the state measure. • Social housing as a percentage of total dwellings is below the state measure. Health status and service utilisation • The rate of cancer incidence per 1,000 males is among the highest in the state. • The percentage of people reporting osteoporosis is among the lowest in the state. • The percentage of people who could definitely access community services and resources is among the highest in the state. -

Mornington Peninsula Facilitator Guide

MORNINGTON PENINSULA FACILITATOR GUIDE AUSTRALIANMornington WINE Peninsula DISCOVERED / Facilitator guide AUSTRALIAN WINE DISCOVERED EDUCATION PROGRAM The comprehensive, free education program providing information, tools and resources to discover Australian wine. To access course presentation, videos and tasting tools, as well as other programs, visit Wine Australia www.australianwinediscovered.com supports the responsible service of alcohol. For enquiries, email [email protected] Mornington Peninsula / Facilitator guide MORNINGTON PENINSULA Ocean Eight, Mornington Peninsula Mornington Eight, Ocean AUSTRALIAN WINE DISCOVERED Mike Aylward, Mike Australia’s unique climate and landscape have fostered a fiercely independent wine scene, home to a vibrant community of growers, winemakers, viticulturists, and vignerons. With more than 100 grape varieties grown across 65 distinct wine regions, we have the freedom to make exceptional wine, and to do it our own way. We’re not beholden by tradition, but continue to push the boundaries in the pursuit of the most diverse, thrilling wines in the world. That’s just our way. Mornington Peninsula / Facilitator guide MORNINGTON PENINSULA: The Mornington Peninsula is a small A STAR ON seaside region making waves with its elegant cool-climate wines. THE RISE - Diverse maritime climate and soils create an array of microsites - Around 200 small-scale vineyards and boutique producers - World-class Pinot Noir plus top- quality Chardonnay and Pinot Gris/ Grigio - Popular tourist destination and foodie hotspot MORNINGTON PENINSULA: Boutique producers A STAR ON THE RISE The Mornington Peninsula is a multi-tonal Tucked into the southern corner of mainland patchwork of around 200 small-scale Australia, the Mornington Peninsula is a vineyards, many of which are family run. -

AUSTRALIAN EDUCATION UNION Victorian Labor

AUSTRALIAN EDUCATION UNION Victorian Branch Victorian Labor MPs We want you to email the MP in the electoral district where your school is based. If your school is not in a Labor held area then please email a Victorian Labor upper house MP who covers your area from the separate list below. Click here if you need to look it up. Email your local MP and cc the Education Minister and the Premier Legislative Assembly MPs (lower house) ELECTORAL DISTRICT MP NAME MP EMAIL MP TELEPHONE Albert Park Martin Foley [email protected] (03) 9646 7173 Altona Jill Hennessy [email protected] (03) 9395 0221 Bass Jordan Crugname [email protected] (03) 5672 4755 Bayswater Jackson Taylor [email protected] (03) 9738 0577 Bellarine Lisa Neville [email protected] (03) 5250 1987 Bendigo East Jacinta Allan [email protected] (03) 5443 2144 Bendigo West Maree Edwards [email protected] 03 5410 2444 Bentleigh Nick Staikos [email protected] (03) 9579 7222 Box Hill Paul Hamer [email protected] (03) 9898 6606 Broadmeadows Frank McGuire [email protected] (03) 9300 3851 Bundoora Colin Brooks [email protected] (03) 9467 5657 Buninyong Michaela Settle [email protected] (03) 5331 7722 Activate. Educate. Unite. 1 Burwood Will Fowles [email protected] (03) 9809 1857 Carrum Sonya Kilkenny [email protected] (03) 9773 2727 Clarinda Meng -

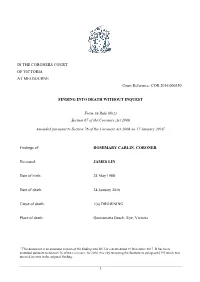

COR 2016 000350 FINDING INTO DEATH WITHOUT INQUEST Form

IN THE CORONERS COURT OF VICTORIA AT MELBOURNE Court Reference: COR 2016 000350 FINDING INTO DEATH WITHOUT INQUEST Form 38 Rule 60(2) Section 67 of the Coroners Act 2008 Amended pursuant to Section 76 of the Coroners Act 2008 on 17 January 20181 Findings of: ROSEMARY CARLIN, CORONER Deceased: JAMES LIN Date of birth: 24 May 1988 Date of death: 24 January 2016 Cause of death: 1(a) DROWNING Place of death: Gunnamatta Beach, Rye, Victoria 1 This document is an amended version of the finding into Mr Lin’s death dated 19 December 2017. It has been amended pursuant to Section 76 of the Coroners Act 2008 (Vic) by removing the footnote to paragraph [19] which was inserted in error in the original Finding. 1 HER HONOUR: Background 1. James Lin was born on 24 May 1988. He was 27 years old when he died from drowning at Gunnamatta Beach on the Mornington Peninsula. 2. Mr Lin lived in Box Hill with his mother Alice Lin. Other members of his family lived in Taiwan. The coronial investigation 3. Mr Lin’s death was reported to the Coroner as it fell within the definition of a reportable death in the Coroners Act 2008 (the Act). Reportable deaths include deaths that are unexpected, unnatural or violent or result from accident or injury. 4. Coroners independently investigate reportable deaths to find, if possible, identity, medical cause of death and with some exceptions, surrounding circumstances. Surrounding circumstances are limited to events which are sufficiently proximate and causally related to the death. Coroners make findings on the balance of probabilities, not proof beyond reasonable doubt.2 5. -

Outer Melbourne Connect | Special Report October 2008

• transport • community • industry outer Special Report | October 2008 melbourne outer melbourne connect | special report October 2008 Melbourne is booming. Every week, another 1,200 people call Melbourne home and the Victorian Government now predicts that we will become the nation’s largest city within 20 years. This rapid population growth has strained Melbourne’s transport system and threatens Victoria’s economic prosperity and Melbourne’s liveability. The region feeling the pain the outer most is outer Melbourne, home to over half of Melbourne’s population and set for continued rapid growth. melbourne In 2002, RACV produced a special report titled ‘The Missing Links’, which presented a plan for upgrading transport infrastructure in outer metropolitan Melbourne. transport The Missing Links identified seventy-four critical road and public transport projects and a much needed $2.2 billion community investment. Six years on, only half of these projects have been built or had funds committed to build them. The other industry half remain incomplete and the intervening period of strong population and economic growth has created further pressing demands on our transport system. Melbourne’s liveability is recognised worldwide and RACV wants it to stay this way. For this reason, we have again consulted with state and local governments and listened to Members to identify an updated program of works to meet the needs of people living in and travelling through Melbourne’s outer suburbs. RACV presents Outer Melbourne Connect as a responsible blueprint comprising road improvements, rail line extensions and significant public transport service improvements.Connect provides a comprehensive and connected transport network to address the critical backlog of projects in outer Melbourne. -

Book 2 23, 24 and 25 February 2010

PARLIAMENT OF VICTORIA PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY FIFTY-SIXTH PARLIAMENT FIRST SESSION Book 2 23, 24 and 25 February 2010 Internet: www.parliament.vic.gov.au/downloadhansard By authority of the Victorian Government Printer The Governor Professor DAVID de KRETSER, AC The Lieutenant-Governor The Honourable Justice MARILYN WARREN, AC The ministry Premier, Minister for Veterans’ Affairs and Minister for Multicultural Affairs....................................................... The Hon. J. M. Brumby, MP Deputy Premier, Attorney-General and Minister for Racing............ The Hon. R. J. Hulls, MP Treasurer, Minister for Information and Communication Technology, and Minister for Financial Services.............................. The Hon. J. Lenders, MLC Minister for Regional and Rural Development, and Minister for Industry and Trade............................................. The Hon. J. M. Allan, MP Minister for Health............................................... The Hon. D. M. Andrews, MP Minister for Energy and Resources, and Minister for the Arts........... The Hon. P. Batchelor, MP Minister for Police and Emergency Services, and Minister for Corrections................................................... The Hon. R. G. Cameron, MP Minister for Community Development.............................. The Hon. L. D’Ambrosio, MP Minister for Agriculture and Minister for Small Business.............. The Hon. J. Helper, MP Minister for Finance, WorkCover and the Transport Accident Commission, Minister for Water and Minister