The Ravello Dialogues… …And Other Related Documents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ADC Theatre Sound Effects Collection – Track Listings

ADC Theatre Sound Effects Collection – Track Listings Disc: Spectacular SFX Vol. 1 (EMI) (ADC #1) ............................................................................2 Disc: Spectacular SFX Vol. 2 (EMI) (ADC #2) ............................................................................3 Disc: 101 Sound Effects (San Juan EFX002) (ADC #3)..............................................................6 Disc: Workshop of Sound (San Juan EFX004) (ADC #4) ...........................................................7 Disc: Essential Comedy SFX, Vol. 1 BBC CD 843 1984/1991 (ADC #5)...................................8 Disc: Frights of the Night (San Juan EFX001) (ADC #6).............................................................9 Disc: BBC Essential Sound Effects (ADC #7)..............................................................................9 Disc: Essential People SFX BBC CD 863 1993 (ADC #8) ........................................................10 Disc: Essential Crowd SFX BBC CD 862 1993 (ADC #9)..........................................................12 Disc: Essential Sounds of the Countryside BBC CD 861 1993 (ADC #10) ...............................13 Disc: Essential Sounds of the City BBC CD 860 1993 (ADC #11)...........................................14 Disc: Essential Foreign SFX BBC CD 870 1993 (ADC #12) ....................................................15 Disc: Essential Weather SFX BBC CD 868 1993 (ADC #13)....................................................16 Disc: Essential Seasonal Birdsong BBC CD 846 (ADC -

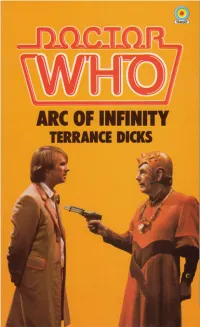

Doctor Returns to Gallifrey, He Learns That His Bio Data Extract Has Been Stolen from the Time Lords’ Master Computer Known As the Matrix

When the Doctor returns to Gallifrey, he learns that his bio data extract has been stolen from the Time Lords’ master computer known as the Matrix. The bio data extract is a detailed description of the Doctor’s molecular structure—and this information, in the wrong hands, could be exploited with disastrous effect. The Gallifreyan High Council believe that anti-matter will be infiltrated into the universe as a result of the theft. In order to render the information useless, they decide the Doctor must die... Among the many Doctor Who books available are the following recently published titles: Doctor Who and the Sunmakers Doctor Who Crossword Book Doctor Who — Time-Flight Doctor Who — Meglos Doctor Who — Four to Doomsday Doctor Who — Earthshock GB £ NET +001.35 ISBN 0-426-19342-3 UK: £1.35 *Australia: $3.95 *Recommended Price ,-7IA4C6-bjdecf-:k;k;L;N;p TV tie-in DOCTOR WHO ARC OF INFINITY Based on the BBC television serial by Johnny Byrne by arrangement with the British Broadcasting Corporation TERRANCE DICKS A TARGET BOOK published by The Paperback Division of W. H. Allen & Co. Ltd A Target Book Published in 1983 by the Paperback Division of W.H. Allen & Co. Ltd A Howard & WyndhamCompany 44 Hill Street, London W1X 8LB First published in Great Britain by W.H. Allen & Co. Ltd 1983 Novelisation copyright © Terrance Dicks 1983 Original script copyright © Johnny Byrne 1982 ‘Doctor Who’ series copyright © British Broadcasting Corporation 1982, 1983 Printed and bound in Great Britain by Anchor Brendon Ltd, Tiptree, Essex ISBN 0 426 19342 3 This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser. -

February 2018: Primetime Alaskapublic.Org

schedule available online: February 2018: Primetime alaskapublic.org ver. 2 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 Father Brown: Death In Paradise: Miss Fisher's Murder Mysteries: Hinterland: Amanpour on NHK Thu 2/1 The Daughters of Jerusalem Unlike Father, Unlike Son Game, Set, Murder Both Barrels (pt. 2) PBS Newsline Washington Alaska Great Performances: Nas Alicia Keys - Landmarks Austin City Limits: Run the Amanpour on NHK Fr 2/2 Week Insight Live from Kennedy Center Live Jewels PBS Newsline Keeping Up As Time Miss Fisher's Murder Mysteries: Doctor Who Tom Baker Movies: Stories from Front and Center: Sat 2/3 Appearances Goes By Game, Set, Murder The Leisure Hive the Stage Miranda Lambert Victoria on Masterpiece: Victoria on Masterpiece: Queen Elizabeth's Secret Call the Midwife Season 6 Victoria on Masterpiece: Sun 2/4 Entente Cordiale Faith, Hope, Charity Agents (pt. 2) (pt. 5) Faith, Hope, Charity Antiques Roadshow: Antiques Roadshow: Amanpour on NHK Mon 2/5 Independent Lens: Winnie On Story New Orleans, LA (pt. 2) Jacksonville, FL (pt. 1) PBS Newsline We'll Meet Again: Africa's Greatest Civilizations: Amanpour on NHK Tue 2/6 Gilded Age: American Experience Lost Children of Vietnam Origins PBS Newsline Animals with Cameras - a NOVA: Impossible Builds: Globe Trekker: Northeast Amanpour on NHK Wed 2/7 Nature Mini-Series (pt. 2) First Face of America The Scorpion Tower England PBS Newsline Father Brown: Death In Paradise: Miss Fisher's Murder Mysteries: Hinterland: Amanpour on NHK Thu 2/8 The Three Tools of Death Death of a Detective Death Do Us Part Return to Pontarfynach (pt. -

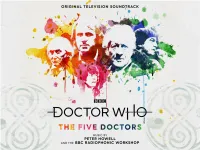

Digital Booklet

ORIGINAL TELEVISION SCORE ADDITIONAL CUES FOR 4-PART VERSION 01 Doctor Who - Opening Theme (The Five Doctors) 0.36 34 End of Episode 1 (Sarah Falls) 0.11 02 New Console 0.24 35 End of Episode 2 (Cybermen III variation) 0.13 03 The Eye of Orion 0.57 36 End of Episode 3 (Nothing to Fear) 0.09 04 Cosmic Angst 1.18 05 Melting Icebergs 0.40 37 The Five Doctors Special Edition: Prologue (Premix) 1.22 06 Great Balls of Fire 1.02 07 My Other Selves 0.38 08 No Coordinates 0.26 09 Bus Stop 0.23 10 No Where, No Time 0.31 11 Dalek Alley and The Death Zone 3.00 12 Hand in the Wall 0.21 13 Who Are You? 1.04 14 The Dark Tower / My Best Enemy 1.24 15 The Game of Rassilon 0.18 16 Cybermen I 0.22 17 Below 0.29 18 Cybermen II 0.58 19 The Castellan Accused / Cybermen III 0.34 20 Raston Robot 0.24 21 Not the Mind Probe 0.10 22 Where There’s a Wind, There’s a Way 0.43 23 Cybermen vs Raston Robot 2.02 24 Above and Between 1.41 25 As Easy as Pi 0.23 26 Phantoms 1.41 27 The Tomb of Rassilon 0.24 28 Killing You Once Was Never Enough 0.39 29 Oh, Borusa 1.21 30 Mindlock 1.12 31 Immortality 1.18 32 Doctor Who Closing Theme - The Five Doctors Edit 1.19 33 Death Zone Atmosphere 3.51 SPECIAL EDITION SCORE 56 The Game of Rassilon (Special Edition) 0.17 57 Cybermen I (Special Edition) 0.22 38 Doctor Who - Opening Theme (The Five Doctors Special Edition) 0.35 58 Below (Special Edition) 0.43 39 The Five Doctors Special Edition: Prologue 1.17 59 Cybermen II (Special Edition) 1.12 40 The Eye of Orion / Cosmic Angst (Special Edition) 2.22 60 The Castellan Accused / Cybermen -

Full Circle Sampler

The Black Archive #15 FULL CIRCLE SAMPLER By John Toon Second edition published February 2018 by Obverse Books Cover Design © Cody Schell Text © John Toon, 2018 Range Editors: James Cooray Smith, Philip Purser-Hallard John would like to thank: Phil and Jim for all of their encouragement, suggestions and feedback; Andrew Smith for kindly giving up his time to discuss some of the points raised in this book; Matthew Kilburn for using his access to the Bodleian Library to help me with my citations; Alex Pinfold for pointing out the Blake’s 7 episode I’d overlooked; Jo Toon and Darusha Wehm for beta reading my first draft; and Jo again for giving me the support and time to work on this book. John Toon has asserted his right to be identified as the author of this Work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding, cover or e-book other than which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent publisher. 2 For you. Yes, you! Go on, you deserve it. 3 Also Available The Black Archive #1: Rose by Jon Arnold The Black Archive #2: The Massacre by James Cooray Smith The Black Archive #3: The Ambassadors of Death by LM Myles The Black Archive #4: Dark Water / Death in Heaven by Philip Purser-Hallard The Black Archive #5: Image of the Fendahl -

Doctor Who Assistants

COMPANIONS FIFTY YEARS OF DOCTOR WHO ASSISTANTS An unofficial non-fiction reference book based on the BBC television programme Doctor Who Andy Frankham-Allen CANDY JAR BOOKS . CARDIFF A Chaloner & Russell Company 2013 The right of Andy Frankham-Allen to be identified as the Author of the Work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Copyright © Andy Frankham-Allen 2013 Additional material: Richard Kelly Editor: Shaun Russell Assistant Editors: Hayley Cox & Justin Chaloner Doctor Who is © British Broadcasting Corporation, 1963, 2013. Published by Candy Jar Books 113-116 Bute Street, Cardiff Bay, CF10 5EQ www.candyjarbooks.co.uk A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted at any time or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the copyright holder. This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not by way of trade or otherwise be circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published. Dedicated to the memory of... Jacqueline Hill Adrienne Hill Michael Craze Caroline John Elisabeth Sladen Mary Tamm and Nicholas Courtney Companions forever gone, but always remembered. ‘I only take the best.’ The Doctor (The Long Game) Foreword hen I was very young I fell in love with Doctor Who – it Wwas a series that ‘spoke’ to me unlike anything else I had ever seen. -

Friday, July 1St

Programming Schedule Listing Friday, July 1st 12:00 PM Dr. Who Room DOCTOR WHO with Peter Capaldi: "The Last Christmas" (1 Hour, 30 Minutes Video Rating: PG) Clara discovers Santa Claus and his two snarky elves Ian and Wolfe on her rooftop early Christmas morning, followed by the arrival of the Doctor, whom she hasn't seen in months. Meanwhile, a group of scientists at the North Pole are trying to save their fellow crewmates, who have been taken over by strange parasitic aliens. Can the Doctor and Clara save Christmas for the survivors? Not everything is as it seems... Anime Room Ace Attorney (SciFi/Mystery) (Rated: Teen) (2 Hours Video Rating: PG13) In the near future, Japan's legal system has become a complicated mess and the courtroom is dominated by powerful and greedy law firms. Based on the popular Nintendo DS game series, follow Ace Attorney Phoenix Wright as he blazes through the courts for righteousness and justice. OBJECTION!!! 1:30 PM Dr. Who Room FIREBALL XL5: "Planet 46" (30 Minutes Video Rating: G) Gerry Anderson's legendary Super Marionation series returns with the adventures of Col. Steve Zodiac and his friends as they explore the galaxy! In this episode, Fireball XL5 intercepts a planetoic missile aimed straight for Earth from the world designated as Plaent 46 2:00 PM Dr. Who Room FIREBALL XL5: "Wings of Danger" (30 Minutes Video Rating: G) Steve is poisoned by a robotic bird while investigating strange signals on Planet 46. Anime Room Sousei no Onmyouji (Science Fantasy) (Rated: Teen) (2 Hours Video Rating: PG13) Onmyouji are powerful Shinto Buddhist priests and monks that specialize in the management, exorcism, and rituals of the spirit world. -

February 2018: Early Morning Alaskapublic.Org

schedule available online: February 2018: Early Morning alaskapublic.org ver. 2 12:00am 12:30am 1:00am 1:30am 2:00am 2:30am 3:00am 3:30am 4:00am 4:30am Animals with Cameras: A Triangle Fire: American We'll Meet Again: Rescued Thu 2/1 NOVA: The Impossible Flight Nature Mini-series (pt. 1) Experience from Mount St. Helens Father Brown: Death In Paradise: Miss Fisher's Murder Mysteries: Hinterland: NOVA: Fr 2/2 The Daughters of Jerusalem Unlike Father, Unlike Son Game, Set, Murder Both Barrels (pt. 2) Petra - Lost City of Stone Washington Washington Great Performances: Nas Alicia Keys - Landmarks Triangle Fire: American Sat 2/3 Week Special This Old House Hour Week Live from Kennedy Center Live Experience Edition Washington Keeping Up As Time Miss Fisher's Murder Mysteries: Doctor Who Tom Baker Movies: Stories from Washington Sun 2/4 Week Special Appearances Goes By Game, Set, Murder The Leisure Hive the Stage Week Edition Victoria on Masterpiece: Queen Elizabeth's Secret Emery We'll Meet Again: Rescued Mon 2/5 Independent Lens: I am Another you Faith, Hope, & Charity Agents (pt. 2) Blagdon from Mount St. Helens Antiques Roadshow: Antiques Roadshow: Great Performances: Nas Victoria on Masterpiece: Queen Elizabeth's Secret Tue 2/6 New Orleans, LA (pt. 2) Jacksonville, FL (pt. 1) Live from Kennedy Center Faith, Hope, & Charity Agents (pt. 2) We'll Meet Again: Lost Emery Wed 2/7 Gilded Age: American Experience Independent Lens: Winnie Children of Vietnam Blagdon Animals with Cameras: A NOVA: Impossible Builds: Great Performances: Nas We'll Meet Again: Lost Thu 2/8 Nature Mini-series (pt. -

Doctor Who Classic Touches Down on Boxing Day

DOCTOR WHO CLASSIC TOUCHES DOWN ON BOXING DAY London, 20 December 2019: BritBox Becomes Home to Doctor Who Classic on 26th December Doctor Who fans across the land get ready to clear their schedules as the biggest Doctor Who Classic collection ever streamed in the UK launches on BritBox from Boxing Day. From 26th December, 627 pieces of Doctor Who Classic content will be available on the service. This tally is comprised of a mix of episodes, spin-offs, documentaries, telesnaps and more and includes many rarely-seen treasures. Subscribers will be able to access this content via web, mobile, tablet, connected TVs and Chromecast. 129 complete stories, which totals 558 episodes spanning the first eight Doctors from William Hartnell to Paul McGann, form the backbone of the collection. The collection also includes four complete stories; The Tenth Planet, The Moonbase, The Ice Warriors and The Invasion, which feature a combination of original content and animation and total 22 episodes. An unaired story entitled Shada which was originally presented as six episodes (but has been uploaded as a 130 minute special), brings this total to 28. A further two complete, solely animated stories - The Power Of The Daleks and The Macra Terror (presented in HD) - add 10 episodes. Five orphaned episodes - The Crusade (2 parts), Galaxy 4, The Space Pirates and The Celestial Toymaker - bring the total up to 600. Doctor Who: The Movie, An Unearthly Child: The Pilot Episode and An Adventure In Space And Time will also be available on the service, in addition to The Underwater Menace, The Wheel In Space and The Web Of Fear which have been completed via telesnaps. -

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgments ...........................................................................................................................5 Table of Contents ..............................................................................................................................7 Foreword by Gary Russell ............................................................................................................9 Preface ..................................................................................................................................................11 Introduction .......................................................................................................................................13 Chapter 1 The New World ............................................................................................................16 Chapter 2 Daleks Are (Almost) Everywhere ........................................................................25 Chapter 3 The Television Landscape is Changing ..............................................................38 Chapter 4 The Doctor Abroad .....................................................................................................45 Sidebar: The Importance of Earnest Videotape Trading .......................................49 Chapter 5 Nothing But Star Wars ..............................................................................................53 Chapter 6 King of the Airwaves .................................................................................................62 -

Doctor Who: Meglos

DOCTOR WHO MEGLOS By TERRANCE DICKS 1. Abduction of an Earthling People disappear. There's nothing illegal about walking out of your old life, changing your name, getting another job in another town or another country. Sometimes there may be a more sinister explanation. In criminal circles people have been known to drop out of sight - and never reappear. There are rumours that the concrete pilings that support some of our new motorways are hiding grisly secrets. Even in a small country like England there are wild stretches where a body can be hidden and never found. Some disappearances have far stranger explanations - like the disappearance of George Morris. Mr Morris was an assistant bank manager in a small country town. Tall, slim, with horn-rimmed glasses and pleasant open face, he was about as average a specimen of his kind as you could wish to find. He was fortunate in that he lived close to his work. Most days he didn't even take the car. Twenty-minutes brisk walking across the common took him from the front door of the little High Street bank, across a pleasantly wild and unspoiled common and up to the front door of the big house in a quiet country lane. On this particular evening he telephoned his wife just before he left the bank and told her, as he told her every weekday evening, that he would be home in twenty minutes. Mrs Morris said, 'Yes, dear,' went to the drinks cabinet and poured him a glass of medium-dry sherry. Twenty minutes later she would hear his key in the lock. -

Ultimateregeneration1.Pdf

First published in England, January 2011 by Kasterborous Books e: [email protected] w: http://www.kasterborous.com ISBN: 978-1-4457-4780-4 (paperback) Ultimate Regeneration © 2011 Christian Cawley Additional copyright © as appropriate is apportioned to Brian A Terranova, Simon Mills, Thomas Willam Spychalski, Gareth Kavanagh and Nick Brown. The moral rights of the authors have been asserted. Internal design and layout by Kasterborous Books Cover art and external design by Anthony Dry Printed and bound by [PRINTER NAME HERE] No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, by photocopying or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage or retrieval systems, without permission in writing from both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book. This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior written consent in any form binding or cover other than that in which it is published for both the initial and any subsequent purchase. 2 ABOUT THE AUTHOR Christian Cawley is a freelance writer and author from the north east of England who has been the driving force behind www.kasterborous.com since its launch in 2005. Christian’s passion for Doctor Who and all things Time Lordly began when he was but an infant; memories of The Pirate Planet and Destiny of the Daleks still haunt him, but his clearest classic Doctor Who memory remains the moment the Fourth Doctor fell from a radio telescope… When the announcement was made in 2003 that Doctor Who would be returning to TV, Christian was nowhere to be seen – in fact he was enjoying himself at the Munich Oktoberfest.