Hindu Ethics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

L,L Ll an EARLY UPANISADIC RE,ADER

AN EARLY UPANISADIC RE,ADER With notes, glossary, and an appendix of related Vedic texts Editedfor the useof Sanskritstudents asa supplementto Lanman'sSariskr it Reader HaNs Flrrunrcn Hocr l l, l i ll MOTILAL BANARSIDASSPUBLISHERS PRIVATE LIMITED . DELHI First Edition : DeLhi 2007 Contents Preface lx Introduction 1 O by Hansllenrich I tock The Texts 25 I: The mystical significanceof the sacrificialhorse (BAU (M) 1:1) 27 ISBN:8l-208 3213,2 (llB) II: A creationmyth associatedwith the agnicayanaand a6vamedha ISBN:81-208321+0 (PB) (from BAU (M) 1:2) 28 III: 'Lead me from untruth(or non-being)to truth(or being) ...' (fromBAU (M) 1:3) 29 MOTILAI, BANARSIDASS IV: Anothercreation myth: The underlying oneness (BAU (M) 1:4) 29 4l U.A. Btrngalow Road, Jawahar Nagar, Dclhi t i0 007 V: A brahminturns to a ksatriyaas teacher, and the parable of Mahalami 8 Chmber, 22 Bhulabhai Desi Road, lvlumbai 400 02ii the sleepingman (from BAU (M) 2:l) 203 Royapetrah High Road, N{ylapore, Chennai 600 004 33 236, 9th N{ain III Block,Jayanagar, Bangalore 560 0l I VI: Yajnavalkyaand Maitreyi (BAU (M) 2:a) J+ Sanas Plaza, 1302 Baji Rao Road, pune 4l I 002 8 Camac Street, Kolkara 700 0 I 7 VII: Ydjffavalkya'sdisputations at the assemblyof King Janaka,1: Ashok Rajparh, Patna 800 004 The cows andthe hotr A6vala(BAU (M) 3:l) 36 Chowk, Varanasi 221 001 VIII: Yajfravalkya'sdisputations at the assemblyof King Janaka,2: Releasefrom "re-death"(BAU (M) 3:3) 38 IX Ydjfravalkya'sdisputations at the assemblyof King Janaka,3: VacaknaviGargi challengesYajfravalkya (BAU (M) 3:8) 39 X: Yajiiavalkya'sdisputations at the assemblyof King Janaka,4: Afr ifr, and VidagdhaSakalya's head flies apart(from BAU (M) 3:9) 40 XI: The beginningof Svetaketu'sinstruction in the transcendental unity of everything(from ChU 6:1-2) 42 XII: The parablesof the fig treeand of the salt,and ilr"trTR (ChU 6:12and 13) +J XIII: The significanceof 3:r (ChU 1:1 with parallelsfrom the Jaiminiya-, , Jaiminiya-Upanisad-,and Aitareya-Brahmanas,and from the Taittiriya- Aranyaka) 44 l. -

In the Name of Krishna: the Cultural Landscape of a North Indian Pilgrimage Town

In the Name of Krishna: The Cultural Landscape of a North Indian Pilgrimage Town A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Sugata Ray IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Frederick M. Asher, Advisor April 2012 © Sugata Ray 2012 Acknowledgements They say writing a dissertation is a lonely and arduous task. But, I am fortunate to have found friends, colleagues, and mentors who have inspired me to make this laborious task far from arduous. It was Frederick M. Asher, my advisor, who inspired me to turn to places where art historians do not usually venture. The temple city of Khajuraho is not just the exquisite 11th-century temples at the site. Rather, the 11th-century temples are part of a larger visuality that extends to contemporary civic monuments in the city center, Rick suggested in the first class that I took with him. I learnt to move across time and space. To understand modern Vrindavan, one would have to look at its Mughal past; to understand temple architecture, one would have to look for rebellions in the colonial archive. Catherine B. Asher gave me the gift of the Mughal world – a world that I only barely knew before I met her. Today, I speak of the Islamicate world of colonial Vrindavan. Cathy walked me through Mughal mosques, tombs, and gardens on many cold wintry days in Minneapolis and on a hot summer day in Sasaram, Bihar. The Islamicate Krishna in my dissertation thus came into being. -

A Political Companion to Henry David Thoreau

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Literature in English, North America English Language and Literature 6-11-2009 A Political Companion to Henry David Thoreau Jack Turner University of Washington Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Thanks to the University of Kentucky Libraries and the University Press of Kentucky, this book is freely available to current faculty, students, and staff at the University of Kentucky. Find other University of Kentucky Books at uknowledge.uky.edu/upk. For more information, please contact UKnowledge at [email protected]. Recommended Citation Turner, Jack, "A Political Companion to Henry David Thoreau" (2009). Literature in English, North America. 70. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/upk_english_language_and_literature_north_america/70 A Political Companion to Henr y David Thoreau POLITIcaL COMpaNIONS TO GREat AMERIcaN AUthORS Series Editor: Patrick J. Deneen, Georgetown University The Political Companions to Great American Authors series illuminates the complex political thought of the nation’s most celebrated writers from the founding era to the present. The goals of the series are to demonstrate how American political thought is understood and represented by great Ameri- can writers and to describe how our polity’s understanding of fundamental principles such as democracy, equality, freedom, toleration, and fraternity has been influenced by these canonical authors. The series features a broad spectrum of political theorists, philoso- phers, and literary critics and scholars whose work examines classic authors and seeks to explain their continuing influence on American political, social, intellectual, and cultural life. This series reappraises esteemed American authors and evaluates their writings as lasting works of art that continue to inform and guide the American democratic experiment. -

Immortal Buddhas and Their Indestructible Embodiments – the Advent of the Concept of Vajrakāya

JIABS Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies Volume 34 Number 1–2 2011 (2012) 22011_34_JIABS_GESAMT.indb011_34_JIABS_GESAMT.indb a 111.04.20131.04.2013 009:11:429:11:42 The Journal of the International EDITORIAL BOARD Association of Buddhist Studies (ISSN 0193-600XX) is the organ of the International Association of Buddhist KELLNER Birgit Studies, Inc. As a peer-reviewed journal, KRASSER Helmut it welcomes scholarly contributions Joint Editors pertaining to all facets of Buddhist Studies. JIABS is published twice yearly. BUSWELL Robert The JIABS is now available online in open access at http://archiv.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/ CHEN Jinhua ojs/index.php/jiabs/index. Articles become COLLINS Steven available online for free 60 months after their appearance in print. Current articles COX Collet are not accessible online. Subscribers can GÓMEZ Luis O. choose between receiving new issues in HARRISON Paul print or as PDF. VON HINÜBER Oskar Manuscripts should preferably be sub- JACKSON Roger mitted as e-mail attachments to: [email protected] as one single fi le, JAINI Padmanabh S. complete with footnotes and references, KATSURA Shōry in two diff erent formats: in PDF-format, and in Rich-Text-Format (RTF) or Open- KUO Li-ying Document-Format (created e.g. by Open LOPEZ, Jr. Donald S. O ce). MACDONALD Alexander Address books for review to: SCHERRER-SCHAUB Cristina JIABS Editors, Institut für Kultur- und SEYFORT RUEGG David Geistesgeschichte Asiens, Apostelgasse 23, A-1030 Wien, AUSTRIA SHARF Robert STEINKELLNER Ernst Address subscription -

93. Sudarsana Vaibhavam

. ïI>. Sri sudarshana vaibhavam sadagopan.org sadagopan.org sadagopan.org sadagopan.org Annotated Commentary in English By: Oppiliappan Koil SrI VaradAchAri SaThakopan 1&&& Sri Anil T (Hyderabad) . ïI>. SWAMY DESIKAN’S SHODASAYUDHAA STHOTHRAM sadagopan.org sadagopan.org sadagopan.org sadagopan.org ANNOTATED COMMENTARY IN ENGLISH BY: OPPILIAPPAN KOIL SRI VARADACHARI SATHAGOPAN 2 CONTENTS Sri Shodhasayudha StOthram Introduction 5 SlOkam 1 8 SlOkam 2 9 SlOkam 3 10 SlOkam 4 11 SlOkam 5 12 SlOkam 6 13 SlOkam 7 14 sadagopan.org sadagopan.org SlOkam 8 15 sadagopan.org sadagopan.org SlOkam 9 16 SlOkam 10 17 SlOkam 11 18 SlOkam 12 19 SlOkam 13 20 SlOkam 14 21 SlOkam 15 23 SlOkam 16 24 3 SlOkam 17 25 SlOkam 18 26 SlOkam 19 (Phala Sruti) 27 Nigamanam 28 Sri Sudarshana Kavacham 29 - 35 Sri Sudarshana Vaibhavam 36 - 42 ( By Muralidhar Rangaswamy ) Sri Sudarshana Homam 43 - 46 Sri Sudarshana Sathakam Introduction 47 - 49 sadagopan.org sadagopan.org sadagopan.org sadagopan.org Thiruvaymozhi 7.4 50 - 56 SlOkam 1 58 SlOkam 2 60 SlOkam 3 61 SlOkam 4 63 SlOkam 5 65 SlOkam 6 66 SlOkam 7 68 4 . ïI>. ïImteingmaNt mhadeizkay nm> . ;aefzayuxStaeÇt!. SWAMY DESIKAN’S SHODASAYUDHA STHOTHRAM Introduction sadagopan.org sadagopan.org Shodasa Ayutha means sixteen weapons of Sri Sudarsanaazhwar. This sadagopan.org sadagopan.org Sthothram is in praise of the glory of Sri Sudarsanaazhwar who is wielding sixteen weapons all of which are having a part of the power of the Chak- rAudham bestowed upon them. This Sthothram consists of 19 slOkams. The first slOkam is an introduction and refers to the 16 weapons adorned by Sri Sudarsana BhagavAn. -

What Is Samadhi?

What is samadhi? Search Now! Shopping | Classifieds | Astrology | News | Chennai Yellow Pages ChennaiOnline Web Dec 27, 2006 Wed Cricket Education Forum Friendship Health Hotels Jobs Matrimonial Movies Music Property Bazaar Panorama Tamil Songs Parthiba - Margazhi :: News :: Events :: Search for Doctors :: Health - Management :: Heart :: Yoga :: Emergency :: ENT Corner :: Hospitals :: What You Eat :: Insurance :: Homeopathy Deep Web Medical Search What is samadhi? krishcricket.com egames The word ‘samadhi’ has been largely misunderstood. People think it means a death-like situation. The word literally means ‘sama’ and ‘dhi’. ‘Sama’ means equanimity and ‘dhi’ denotes ‘buddhi’. If you reach that kind of equanamous state of intellect, it is known as ‘samadhi’. What it means by equanamous state of intellect is this: only when the intellect is functioning, you are able to discriminate between one RSS / XML thing and the other. The discrimination that this is this and this is that is there only because the intellect is functioning. COL Instant The moment you drop the intellect or transcend the Messenger intellect, this discrimination does not exist. Now everything Finance becomes one whole, which is a reality. Get Marriage Proposal by Email Everything just becomes one whole. In this state, there is for FREE! Heart Attack- no time and space. You may think the man had been in samadhi for three days. For Horoscope with 10 Knowledge is him, it was just a few moments – it just passes off like that. Lifetimes can pass off like this. Year's Prediction Protection http://www.chennaionline.com/health/yoga/2004/01samadhi.asp (1 of 4)12/27/2006 3:12:57 PM What is samadhi? There are legends where it is said Donate to Sri Consult online our that there have been yogis who lived Lakshmikubera Trust Homeopath, up to 400-500 years and that some Wedding Planner Dr S of them are still alive. -

Theoretical Issues

PA RT I Theoretical Issues 1 Colonialism and the Construction of Hinduism 23 Gauri Viswanathan 2 Orientalism and Hinduism 45 David Smith CHAPTER 1 Colonialism and the Construction of Hinduism Gauri Viswanathan In The Hill of Devi, a lyrical collection of essays and letters recounting his travels in India, E. M. Forster describes his visit to a Hindu temple as a tourist’s pil- grimage driven by a mixture of curiosity, disinterestedness, loathing, and even fear. Like the Hindu festival scene he paints in A Passage to India, the Gokul Ashtami festival he witnesses is characterized as an excess of color, noise, ritual, and devotional fervor. Forcing himself to refrain from passing judgment, Forster finds it impossible to retain his objectivity the closer he approaches the shrine, the cavern encasing the Hindu stone images (“a mess of little objects”) which are the object of such frenzied devotion. Encircled by the press of ardent devo- tees, Forster is increasingly discomfited by their almost unbearable delirium. Surveying the rapt faces around him, he places the raucous scene against the more reassuring memory of the sober, stately, and measured tones of Anglican worship. His revulsion and disgust reach a peak as he advances toward the altar and finds there only mute, gaudy, and grotesque stone where others see tran- scendent power (Forster 1953: 64). And then, just as Forster is about to move along in the ritual pilgrims’ for- mation, he turns back and sees the faces of the worshippers, desperate in their faith, hopelessly trusting in a power great enough to raise them from illness, poverty, trouble, and oppression. -

Temperance in the Modern World

Temperance in the modern world In Pope Francis’ continuing diagnosis of the world’s ills, elaborated on thoroughly in his most recent encyclical Laudato Si‘ (On Care for Our Common Home), consumerism — excess consumption of material goods — ranks consistently at or near the top of the list. Consumerism is one face of the maldistribution of wealth, the other face of which is poverty. The pope calls it a “poison” that reflects “emptiness of meaning and values.” Collective consumerism is among the symptoms of what Pope St. John Paul II called “superdevelopment.” This aberration, he explained, arises from “excessive availability of every kind of material goods, for the benefit of certain social groups” and is expressed in an obsessive quest to own and consume more and more (Sollicitudo Rei Socialis, No. 28). The cure for this disease of the spirit, considered as a social problem, is the practice of social justice in economic policies, practices and laws. On the individual level, too, each of us is tempted to consumerism and has social justice responsibilities. But how are ordinary people to practice social justice? The answer is temperance. Cumulatively, temperance can make a real contribution to social justice. One person living temperately gives a good example. A multitude living temperately can change a nation, or even the world, for the better. Pope Francis makes much the same point in his encyclical, Laudato Si‘, where he uses the word “sobriety” to describe an attitude equivalent to temperance. Living this way, he writes, means “living life to the full … learning familiarity with the simplest things and how to enjoy them” (No. -

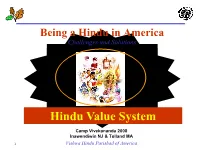

Hindu Value System

Being a Hindu in America Challenges and Solutions Hindu Value System Camp Vivekananda 2008 Inawendiwin NJ & Tolland MA 1 Vishwa Hindu Parishad of America The Ten Attributes of Hindu Dharma VHPA Camp 2 Hindu Value System Hindu Dharma Lakshanas (attributes) Lakshnas Public Visible Attributes Domain Kshama Damah Asteya Dhriti Forgiveness Self Control Identity: (Geeta) Fortitude Honesty Visible/gross: (tilak, janeyu, bindi, clothes, mala, choti.... Saucha Purity festivals, home Indriya-Nigraha environment) Akrodha Sense Control Invisible/subtle: Non-Anger Dhi Satya Intellect TRUTH Vidya Learning Personal Domain 3 Dhriti- Patience Man cannot live without activity The development of an individual, the maintenance of family, social service, etc. is dependent upon action. Ideal example of Dhriti is Shri Ram Root “Dhri” Finish what you start – unwavering commitment to the goal/cause; undaunted, focused, clarity; FORTITUDE Sustaining Power: ONLY Vishnu can sustain; Maintenance (house) requires resources to enhance, preserve and protect (Saraswati, Lakshmi and Shakti) Strength --- only the resourceful can sustain! 4 Kshama – Forgiveness A person who forgives others creates no enemies and adversaries. Sign of stable mind, peaceful heart, and awakened soul. An ideal example of forgiveness is Swami Dayanand. Only the strong can forgive “meaningfully” Only the one who is focused on the larger good, a larger goal, who is unmoved by small disturbances can forget and forgive Kshama implies strength, resourcefulness and commitment to a larger cause Only those who do not feel violated, who have plenty (abundance), have wisdom and vision can see the bigger picture (Vyas, Vishnu & Bhrigu ...) 5 Damah- Control over Mind and Desires It is not possible to overcome wickedness with thoughtless, vengeful approach A person with “damah” quality remains attuned to the noble urges of his self and protects it from ignoble thoughts and rogue desires. -

Hinduism and Hindu Philosophy

Essays on Indian Philosophy UNIVE'aSITY OF HAWAII Uf,FU:{ Essays on Indian Philosophy SHRI KRISHNA SAKSENA UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII PRESS HONOLULU 1970 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 78·114209 Standard Book Number 87022-726-2 Copyright © 1970 by University of Hawaii Press All Rights Reserved Printed in the United States of America Contents The Story of Indian Philosophy 3 Basic Tenets of Indian Philosophy 18 Testimony in Indian Philosophy 24 Hinduism 37 Hinduism and Hindu Philosophy 51 The Jain Religion 54 Some Riddles in the Behavior of Gods and Sages in the Epics and the Puranas 64 Autobiography of a Yogi 71 Jainism 73 Svapramanatva and Svapraka!;>atva: An Inconsistency in Kumarila's Philosophy 77 The Nature of Buddhi according to Sankhya-Yoga 82 The Individual in Social Thought and Practice in India 88 Professor Zaehner and the Comparison of Religions 102 A Comparison between the Eastern and Western Portraits of Man in Our Time 117 Acknowledgments The author wishes to make the following acknowledgments for permission to reprint previously published essays: "The Story of Indian Philosophy," in A History of Philosophical Systems. edited by Vergilius Ferm. New York:The Philosophical Library, 1950. "Basic Tenets of Indian Philosophy," previously published as "Are There Any Basic Tenets of Indian Philosophy?" in The Philosophical Quarterly. "Testimony in Indian Philosophy," previously published as "Authority in Indian Philosophy," in Ph ilosophyEast and West. vo!.l,no. 3 (October 1951). "Hinduism," in Studium Generale. no. 10 (1962). "The Jain Religion," previously published as "Jainism," in Religion in the Twentieth Century. edited by Vergilius Ferm. -

Srimad-Bhagavatam – Canto Ten” by His Divine Grace A.C

“Srimad-Bhagavatam – Canto Ten” by His Divine Grace A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada. Summary: Srimad-Bhagavatam is compared to the ripened fruit of Vedic knowledge. Also known as the Bhagavata Purana, this multi-volume work elaborates on the pastimes of Lord Krishna and His devotees, and includes detailed descriptions of, among other phenomena, the process of creation and annihilation of the universe. His Divine Grace A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada considered the translation of the Bhagavatam his life’s work. COPYRIGHT NOTICE: This is an evaluation copy of the printed version of this book, and is NOT FOR RESALE. This evaluation copy is intended for personal non- commercial use only, under the “fair use” guidelines established by international copyright laws. You may use this electronic file to evaluate the printed version of this book, for your own private use, or for short excerpts used in academic works, research, student papers, presentations, and the like. You can distribute this evaluation copy to others over the Internet, so long as you keep this copyright information intact. You may not reproduce more than ten percent (10%) of this book in any media without the express written permission from the copyright holders. Reference any excerpts in the following way: “Excerpted from “Srimad-Bhagavatam” by A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada, courtesy of the Bhaktivedanta Book Trust International, www.Krishna.com.” This book and electronic file is Copyright 1977-2003 Bhaktivedanta Book Trust International, 3764 Watseka Avenue, Los Angeles, CA 90034, USA. All rights reserved. For any questions, comments, correspondence, or to evaluate dozens of other books in this collection, visit the website of the publishers, www.Krishna.com. -

Religious Fact Sheets

CULTURE AND RELIGION Hinduism Introduction Hinduism is the oldest and the third largest of the world’s major religions, after Christianity and Islam, with 900 million adherents. Hindu teaching and philosophy has had a profound impact on other major religions. Hinduism is a faith as well as a way of life, a world view and philosophy upholding the principles of virtuous and true living for the Indian diaspora throughout the world. The history of Hinduism is intimately entwined with, and has had a profound influence on, the history of the Indian sub-continent. About 80% of the Indian population regard themselves as Hindu. Hindus first settled in Australia during the 19th century to work on cotton and sugar plantations and as merchants. In Australia, the Hindu philosophy is adopted by Hindu centres and temples, meditation and yoga groups and a number of other spiritual groups. The International Society for Krishna Consciousness is also a Hindu organisation. There are more than 30 Hindu temples in Australia, including one in Darwin. Background and Origins Hinduism is also known as Sanatana dharma meaning “immemorial way of right living”. Hinduism is the oldest and most complex of all established belief systems, with origins that date back more than 5000 years in India. There is no known prophet or single founder of Hinduism. Hinduism has a range of expression and incorporates an extraordinarily diverse range of beliefs, rituals and practices, The Hindu faith has numerous schools of thought, has no founder, no organisational hierarchy or structure and no central administration but the concept of duty or dharma, the social and ethical system by which an individual organises his or her life.