University of Dundee Deleuze and the Simulacrum Plummer, Sandra

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CV 2010! Between Times

Clare Strand CV Born 1973! Living and working in Brighton Uk.! www.clarestrand.co.uk! http://clarestrand.tumblr.com! !www.macdonaldstrand.co.uk.! ! ! Solo Exhibitions! 2015 ! Grimaldi Gavin. london . (Title TBC)! 2014! Further Reading. National Museum Of Krakow. Photomonth, Krakow.! 2013! Arles Discovery Award. Rencontre Arles. France.! 2012! Tacschenspielertrick, Forum Fur Fotografie, Cologne. Germany.! 2011! Sleight, Brancolini Grimaldi Gallery, London.! 2009! Clare Strand Fotographie Und Video, Museum Fur Photograhie Braunschweig,! Germany.! Clare Strand Fotographie Und Video, Museum Folkwang, Essen, Germany.! 2008! Clare Strand Recent Works, Fotografins Hus, Stockholm Sweden.! 2005! The Betterment Room – Devices for Measuring Achievement, Senko Studio. Denmark.! 2003! Gone Astray, London College of Communication, London.! 2000! Wasted, Galleri Image, Aarhus, Denmark.! 1998! Seeing Red, Museum of Photography Film and Television, Bradford, England; Imago! Festival, Universidad Salamanca, Spain; Viewpoint Gallery, Salford, England and! Royal Photographic Society, Bath England.! 1997! !The Mortuary, F-Stop Gallery, Bath.! ! Group Exhibitions.! 2015! A History of Art, Archetecture, Design from the 1980’s until Today. curated by Christiane Macel. Center Pompidou. Paris France.! European Portraits ( working title) The Centre of Fine Arts, Brussels, Bozor, Nedermands Fotomuseum , Rotterdam and The National Museum of Photography in Thessaloniki .! 2014! (Mis) Understanding Photography, Folkwang Museum, Essen, Germany. Curated by Florian Ebner! -

Coversheet for Thesis in Sussex Research Online

A University of Sussex PhD thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details 1 UNIVERSITY OF SUSSEX Alice Compton Ph.D Waste of a Nation: Photography, Abjection and Crisis in Thatcher’s Britain May 2016 2 ABSTRACT This examination of photography in Thatcher’s Britain explores the abject photographic responses to the discursive construction of ‘sick Britain’ promoted by the Conservative Party during the years of crisis from the late 1970s onwards. Through close visual analyses of photojournalist, press, and social documentary photographs, this Ph.D examines the visual responses to the Government’s advocation of a ‘healthy’ society and its programme of social and economic ‘waste-saving’. Drawing Imogen Tyler’s interpretation of ‘social abjection’ (the discursive mediation of subjects through exclusionary modes of ‘revolting aesthetics’) into the visual field, this Ph.D explores photography’s implication in bolstering the abject and exclusionary discourses of the era. Exploring the contexts in which photographs were created, utilised and disseminated to visually convey ‘waste’ as an expression of social abjection, this Ph.D exposes how the Right’s successful establishment of a neoliberal political economy was supported by an accelerated use and deployment of revolting photographic aesthetics. -

Melanie Friend | Sussex University

09/28/21 Creative Media: Photography - P4076 - Melanie Friend | Sussex University Creative Media: Photography - P4076 - View Online Melanie Friend Abrahams, Fred, Eric Stover, and Gilles Peress. 2001. A Village Destroyed, May 14, 1999: War Crimes in Kosovo. Berkeley, Calif: University of California Press. Ackroyd, Peter. 2000. London: The Biography. London: Chatto & Windus. Adams, Robert. 2001. Summer Nights. New York: Aperture. ———. 2008. The New West: Landscapes along the Colorado Front Range. New York: Aperture. Adams, Robert, and Fondation Cartier. 2007. Time Passes. Paris: Fondation Cartier pour l’Art Contemporain. ‘Aesthetica: The Art and Culture Magazine.’ n.d. http://www.aestheticamagazine.com/. America & Lewis Hine: Photographs 1904-1940. 1997. New York, N.Y.: Aperture Foundation. Andrews, Philip. 2003. Adobe Photoshop Elements 2.0: A Visual Introduction to Digital Imaging. Oxford: Focal. Appleton, Jay. 1996. The Experience of Landscape. Rev. ed. London: Wiley. Arbus, Diane. 1985. Diane Arbus: Magazine Work. Phaidon. ———. 1995. Untitled. London: Thames & Hudson. Arbus, Diane, Doon Arbus, and Marvin Israel. 1997. Diane Arbus. 25th anniversary ed. New York, N.Y.: Aperture Foundation. Arnatt, Keith, David Hurn, Clare Grafik, and Photographers’ Gallery. 2007. I’m a Real Photographer: Keith Arnatt, Photographs 1974-2002. London: Chris Boot. ‘Art and Design, Photography and Architecture. The Guardian.’ n.d. http://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign. Auge ́ , Marc. 1995. Non-Places: Introduction to the Anthropology of Supermodernity. London: Verso. 1/22 09/28/21 Creative Media: Photography - P4076 - Melanie Friend | Sussex University Avedon, Richard, Michael Juul Holm, and Helle Crenzien. n.d. Richard Avedon Photographs, 1946-2004. Humlebæk, Denmark: Louisiana Museum of Modern Art. Bachelard, Gaston, and M. -

Martin Parr / April 2019 Solo Shows – Current and Upcoming

Martin Parr / April 2019 Solo Shows – Current and Upcoming Only Human: Martin Parr Wolfson and Lerner Galleries, National Portrait Gallery, London, UK 7 Mar to 27 May 2019 Further details here The National Portrait Gallery celebrates a major new exhibition of works by Martin Parr, one of Britain’s best-known and most widely celebrated photographers. Only Human: Martin Parr, brings together some of Parr’s best known photographs with new work by Parr never exhibited before, to focus on one of his most engaging subjects – people. Featuring portraits of people from around the world, the exhibition examines national identity today, both in the UK and abroad with a special focus on Parr’s wry observations of Britishness. Britain in the time of Brexit will be the focus of one section, featuring new works, which reveal Parr’s take on the social climate in the aftermath of the EU referendum. The exhibition will also focus on the British Abroad, including photographs made in British Army camps overseas, and Parr’s long term study of the British ‘Establishment’ including recent photographs taken at Christ’s Hospital school in Sussex, Oxford and Cambridge Universities and the City of London, revealing the obscure rituals and ceremonies of British life. Although best known for capturing ordinary people, Parr has also photographed celebrities throughout his career. For the first time Only Human: Martin Parr will reveal a selection of portraits of renowned personalities, most of which have never been exhibited before, including British fashion legends Vivienne Westwood and Paul Smith, contemporary artists Tracey Emin and Grayson Perry and world-renowned football player Pelé. -

Impact Case Study (Ref3b Institution: UNIVERSITY of the ARTS LONDON

Impact case study (REF3b Institution: UNIVERSITY OF THE ARTS LONDON Unit of Assessment: 34 Title of case study: Photography and the Archive Research Centre (PARC) at the University of the Arts London 1. Summary of the impact Researchers at the Photography and the Archive Research Centre (PARC) study the practice and products of photography in terms of both artistic importance and social relevance, recognising photography’s many roles including its presence in: the art world; reportage; autobiographical practice; and in social and political education. This case study demonstrates PARC’s impact on cultural life via the production of work and curatorial practice, bringing new insights, challenging assumptions, and raising awareness of the role of photographic practice in the public realm. 2. Underpinning research The Centre’s underpinning research is represented by work undertaken at UAL by Professors Val Williams (PARC Director) and Tom Hunter, Brigitte Lardinois (PARC Deputy Director), Jananne Al- Ani (Research Fellow), and Paul Lowe (Course Director, MA Photojournalism and Documentary Photography). Shared research strands include: the history and culture of photography; photojournalism; the documentation of war and conflict; visualization of under-represented groups and issues; social and political relevance of photography; and an exploration of the boundaries between documentation and fiction. Williams’ work on the history and practice of photography in Britain has exposed previously under researched histories. Martin Parr: Photographic Works, Barbican (2002) was the first exhibition to assess Parr’s photographs as a complete body of work. It was threaded with a detailed narrative of Parr’s personal and professional history and set within the broader context of British post-1970 photography. -

SUSAN LIPPER [email protected]

SUSAN LIPPER [email protected] Education 1981-83 MFA Yale University (Photography). 1975 BA Skidmore College (English Literature) including academic credits from Tufts University in London and Dartmouth College. Selected One and Two Person Shows 2012 Motus Fort, Tokyo. 2008 Motus Fort, Tokyo. 2004 The Tang Teaching Museum and Art Gallery, Saratoga Springs, NY. 2000 Galerie Lichtblick, Cologne, Germany. Fotografie Forum International, Frankfurt, Germany. Viewpoint Gallery, Salford, England. 1999-00 New Orleans Museum of Art. Bed and Breakfast, curated by Val Williams, produced by PhotoWorks, touring exhibition in UK. 1997 Zelda Cheatle Gallery, London. BOOKS & Co in association with banning + associates, ltd., New York. 1995 Portfolio Gallery, Edinburgh, Scotland. Cornerhouse Gallery, Manchester, England. 1994 Buhl Foundation Gallery, New York. Arnolfini Gallery, Bristol, England. In the Hollows: Susan Lipper and Wendy Ewald, pARTs Gallery, Minneapolis. The Photographers’ Gallery, London. 1991 Chenango County Arts Council, Norwich, NY with Andrea Modica. 1990-91 Fordham University, Duane Gallery, New York. Selected Group Shows and Juried Exhibitions 2012 Looking at the Land – 21st Century American Views, RISD Museum of Art, Providence. Looking at the Land – 21st Century American Views, Fotoweek DC, Washington DC. Snail Mail, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. Spring has Sprung, Motus Fort, Tokyo. 2011 Blank Canvas Project with Jason Evans, University of Wales, Newport, UK 2010 Myth, Manners and Memory: Photographers of the American South, De La Warr Pavilion, Bexhill on Sea, UK. .Matrix, Philadelphia Photo Arts Center, Philadelphia. 2009 Deep End, The Company, Los Angeles. One Minute Film and Video Festival, organized by Jason Simon and Moyra Davey, Narrowsburg, NY. Thorn Eye, Motus Fort, Tokyo. -

Home Truths: Photography, Motherhood & Loss Friday 11

Home Truths: Photography, Motherhood & Loss Friday 11 October 2013 - Sunday 5 January 2014 Four contemporary photographers explore issues of motherhood and loss in an exhibition curated by Susan Bright. Home Truths presents a series of meditations on maternal relationships that are highly personal, often documentary and that challenge the familiar stereotypes associated with images of motherhood. Curator Susan Bright has selected work by artists Ann Fessler (b. 1950, USA), Tierney Gearon (b. 1963, USA), Miyako Ishiuchi (b. 1947, Japan) and Annu Palakunnathu Matthew (b. 1964, UK) that encompass film, digital collage, still life, reportage and vernacular photography. Set within the context of the Foundling Museum, these works are at once haunting and engaging. Shot with a collage of recent video and archival footage of the farms and rivers of the rural Midwest, Fessler’s Along the Pale Blue River is an autobiographical tale about a young pregnant girl who flees her rural community for a town where she can be invisible, and the daughter who returns forty years later. Through a yearbook picture, Fessler discovers the source of the river from her childhood town and realises it has always flowed from her mother to her. Gearon came to public attention in the UK when her photographs of her children were exhibited as part of I Am A Camera at the Saatchi Gallery in 2001. With The Mother Project she shifts her attention to her elderly mother who is both bipolar and schizophrenic. The project, which took eight years to complete, looks at complex familial relationships and raises issues around ageing, mental health and the role of photography, which is used here as a tool to try and connect and establish a relationship that has been lost (or was never there). -

A Guided Tour

Victoria Sambunaris Untitled, Wendover, UT, 2007 Courtesy of Yancey Richardson Gallery, New York A Guided Tour With the rise of digital photography, one ed to this, these studios specializing in fam- stylized fact that reverberates around pho- ily photography have a lot of preschools, tography circles is that the traditional com- kindergartens, high schools and college mercial studio is dying. While it may be true graduations to visit. Commercially speaking, that there are fewer around and our need to the family is imperative to its success. There visit them less regular, there is still an impor- are also times when this kind of vernacular tant place for them. However many snaps commercial photography can have an inter- you take of your family (and by this I mean esting place in the art gallery and is used to children specifically) there is still an urge to arresting effect in the hands of artists. get “a proper photograph” done and proud- Artistically, the home, domesticity, the ly place it on the mantel piece. For this to family and the familial everyday are a rich- happen, a visit to a studio is necessary. Add- ly mined seam for artists and photogra- Essay By Susan Bright in conjunction with the exhibition Housed curated by Joseph Maida & Katie Murray phers. It’s easy to reel off a long would downgrade it to a “lowbrow the role that technology now has The work they have chosen does list of great bodies of work that art” and love the illicit opportuni- in the home. not simply validate their own prac- have made an important impact in ties it can offer. -

Seeing Colonially: Martin Parr, John Thomson and the British Photographic Imagination

Seeing Colonially: Martin Parr, John Thomson And The British Photographic Imagination by Cammie Jo Tipton-Amini A thesis submitted to the Kathrine G. McGovern College of the Arts in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Art History Chair of Committee: Natilee Harren Committee Member: Roberto Tejada Committee Member: Sandra Zalman University of Houston May 2021 DEDICATION To my grandmother Ruby Anna Wilson and my husband Farhang Amini. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank the following people for their help and support throughout this project. Special thanks to Dr. Harren for the continued support and challenges, equally. Thank you Dr. Tejada and Dr. Zalman for your thoughtful edits, suggestions, recommendations and support. Heartfelt gratitude goes to Dr. Ari for introducing me to postcolonial studies and nineteenth century photography and for taking the time to make me a better writer. Lastly, big respect goes to each in my cohort, Ana, Chesli, Lindsey and Sheri, as we labored through a pandemic, Zoom-school, and local and global catastrophes, to accomplish what we came for. iii ABSTRACT The British contemporary photographer Martin Parr’s collection 7 Colonial Still Lifes (2005) delivers banal and benign images of remnants of British colonization in Sri Lanka. Parr’s early collection The Last Resort (1986) was harshly critiqued for its judgmental lens of the working-class British, with some identifying a contemporary “othering” in Parr’s imagery, yet this line of reasoning was never explored fully. I form a postcolonial reading to argue that what Parr’s critics sensed was the historical legacy of British colonial photography. -

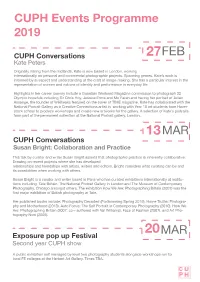

CUPH Programme Design

CUPH Events Programme 2019 CUPH Conversations 27FEB Kate Peters Originally hailing from the midlands, Kate is now based in London, working internationally on personal and commercial photographic projects. Spanning genres, Kate’s work is informed by a respect and understanding of the craft of image-making. She has a particular interest in the representation of women and notions of identity and performance in everyday life. Highlights in her career journey include a Guardian Weekend Magazine commission to photograph 32 Olympic hopefuls including Sir Chris Hoy, Jessica Ennis and Mo Farah and having her portrait of Julian Assange, the founder of Wikilieaks featured on the cover of TIME magazine. Kate has collaborated with the National Portrait Gallery as a Creative Connections artist in working with Year 10 art students from Haver- stock school to produce workshops and create new artworks for the gallery. A selection of Kate’s portraits form part of the permanent collection at the National Portrait gallery, London. 13MAR CUPH Conversations Susan Bright: Collaboration and Practice This talk by curator and writer Susan Bright asserts that photographic practice is inherently collaborative. Drawing on recent projects where she has developed relationships and friendships with artists, writers and editors, Bright considers what curating can be and its possibilities when working with others. Susan Bright is a curator and writer based in Paris who has curated exhibitions internationally at institu- tions including: Tate Britain, The National Portrait Gallery in London and The Museum of Contemporary Photography, Chicago amongst others. The exhibition How We Are: Photographing Britain (2007) was the first major exhibition of British photography at Tate. -

Sarah Pickering CV 2020

Sarah Pickering Date and place of Birth: 1972, Durham Nationality: British website: www.sarahpickering.co.uk Qualifications 2003 - 2005 MA Photography Royal College of Art 1992 - 1995 BA(hons) Photographic Studies, University of Derby 1991 - 1992 Foundation Certificate in Art and Design, Newcastle College Solo Exhibitions 2019 Pickpocket Performance, Camberwell Space, London 2016 Manifesta 11 Pickpocket Performance Cabaret der Künstler - Zunfthaus Voltaire, Artists Guild, Zurich 2015 Art & Antiquities, Format Festival, Evidence, Derby Museum & Art Gallery 2014 Aim & Fire DLI Museum & Durham Art Gallery 2011 Art & Antiquities, Meessen De Clercq, Brussels 2010 Incident Control, Museum of Contemporary Photography (MoCP) Chicago 2009 Explosions, Meessen De Clercq, Brussels Holding Fire Ffotogallery, Wales 2008 Incident Phoenix Gallery, Brighton Fire Scene Daniel Cooney Fine Art, New York 2007 Explosion Photographers Gallery, London 2006 Sarah Pickering, PynerContreras, Cultural Fair, Mexico Explosion Daniel Cooney Fine Art, New York Group Exhibitions (selected) *denotes catalogue 2019 Flashes to Ashes - Fire in British Art, Royal West of England Academy, Bristol* Study for Fiction Plane 1, curated installation by Julia Weist, Shed, New York Rehearsing the Real, curated by Tom Lovelace, Peckham 24 Moving the Image, curated by Duncan Wooldridge,Camberwell Space 2018 Destruction in Art DIAS 2.0, Chisenhale Studios 2017 Something Fierce, Lannan Foundation, Santa Fe, USA SWAP Edition 1 : AD HOC, Castor Gallery, Deptford 2016 Manifesta 11 – Historical -

TRUST/Vertrauen Leipzig, November 12, 2020

f/stop - 9. Festival für Fotografie Leipzig 2021 PRESS RELEASE TRUST/vertrauen Leipzig, November 12, 2020 contact: [email protected] f/stop is delighted to announce the appointment of Susan Bright (London) and Nina Strand (Oslo) as curators for the ninth festival edition, to be held in Leipzig from June 25 to July 4, 2021. The curators were chosen by the advisory board established in 2020, consisting of Kathrin Schönegg (C/O Berlin), Steffen Siegel (University of Folkwang), Christina Töpfer (Camera Austria) Nadine Wietlisbach (Fotomuseum Winterthur) and Jan Wenzel (Spector Books Leipzig). "Our theme TRUST/vertrauen for f/stop 2021 is informed by our belief that trust is the currency of the 21st Century," says Nina Strand. "At the heart of the curatorial concept is a programme that can help us better understand our world, our place in it and our path through the medium of photography," adds Susan Bright. The timeliness, topicality and relevance to this theme is clear. Trust is no longer what happens if we look eye to eye – it also needs to be generated and maintained for the digital space. Despite all advances, challenges, and risks, trust issues will become increasingly critical for human and technological interaction as the century develops. This edition of f/stop has been conceived with the view that a festival must be viewed as an expansive on-going discourse, and as a mode of reflection that reaches outwards as well as f/stop being challenged by the structures that form it. It will differ Festival für Fotografie from former editions by balancing globalism and locality and Leipzig by asking questions about the role of a photo festival in a post www.f-stop-leipzig.de pandemic environment.