The Mass (Re)Production of Female

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aerospace Dimensions Leader's Guide

Leader Guide www.capmembers.com/ae Leader Guide for Aerospace Dimensions 2011 Published by National Headquarters Civil Air Patrol Aerospace Education Maxwell AFB, Alabama 3 LEADER GUIDES for AEROSPACE DIMENSIONS INTRODUCTION A Leader Guide has been provided for every lesson in each of the Aerospace Dimensions’ modules. These guides suggest possible ways of presenting the aerospace material and are for the leader’s use. Whether you are a classroom teacher or an Aerospace Education Officer leading the CAP squadron, how you use these guides is up to you. You may know of different and better methods for presenting the Aerospace Dimensions’ lessons, so please don’t hesitate to teach the lesson in a manner that works best for you. However, please consider covering the lesson outcomes since they represent important knowledge we would like the students and cadets to possess after they have finished the lesson. Aerospace Dimensions encourages hands-on participation, and we have included several hands-on activities with each of the modules. We hope you will consider allowing your students or cadets to participate in some of these educational activities. These activities will reinforce your lessons and help you accomplish your lesson out- comes. Additionally, the activities are fun and will encourage teamwork and participation among the students and cadets. Many of the hands-on activities are inexpensive to use and the materials are easy to acquire. The length of time needed to perform the activities varies from 15 minutes to 60 minutes or more. Depending on how much time you have for an activity, you should be able to find an activity that fits your schedule. -

January 2020 SHARING ACOUSTIC MUSIC for 36 YEARS Issue 417

January 2020 SHARING ACOUSTIC MUSIC for 36 YEARS Issue 417 www.silverstrings.org PERKY PEGGY'S PONDERINGS___ Peggy Kustra That brings us to the Christmas dinner. Once again, Happy Happy New Year! Julie Kafkas & Laurie Patterson helped Sandi create What an awesome Christmas run we had. Thank those fun Christmas tree gnomes for the tables, and you everyone for showing up to playdates and Santa had so many helpers for set-up & clean-up… performing so well. Kudos to all of you! Marsha THANK YOU all for allowing US to enjoy the party! A Kozlowski put a wonderful repertoire together and the lot of work goes into making these programs run audiences loved it. She also set up many seating smoothly, and we are so very fortunate to have such a charts, starter charts, and suffered many personal snow wonderful SSDS family to back us up. Because of the squalls. Through it all she was patient and gracious. In cooperation, we look forward to continuing to serve the other words Marsha.....a job well done. club as your VP's of programs through 2020. The New Board members seem to be full of energy THANK YOU ALL !!!!! and ideas. We will have a great year. Our next event is Variety Night at the end of January. What do we have ahead of us in the year 2020? We Start polishing your acts ! We look forward to seeing & hearing them. HUGS to you all !!! have music, friendship, fellowship, variety nights, picnic, campout, banquet, giggles, grins, new music, old music ….Sandi & Bob [email protected] 734-663-7974 and perhaps a surprise or two. -

Loki Production Brief

PRODUCTION BRIEF “I am Loki, and I am burdened with glorious purpose.” —Loki arvel Studios’ “Loki,” an original live-action series created exclusively for Disney+, features the mercurial God of Mischief as he steps out of his brother’s shadow. The series, described as a crime-thriller meets epic-adventure, takes place after the events Mof “Avengers: Endgame.” “‘Loki’ is intriguingly different with a bold creative swing,” says Kevin Feige, President, Marvel Studios and Chief Creative Officer, Marvel. “This series breaks new ground for the Marvel Cinematic Universe before it, and lays the groundwork for things to come.” The starting point of the series is the moment in “Avengers: Endgame” when the 2012 Loki takes the Tesseract—from there Loki lands in the hands of the Time Variance Authority (TVA), which is outside of the timeline, concurrent to the current day Marvel Cinematic Universe. In his cross-timeline journey, Loki finds himself a fish out of water as he tries to navigate—and manipulate—his way through the bureaucratic nightmare that is the Time Variance Authority and its by-the-numbers mentality. This is Loki as you have never seen him. Stripped of his self- proclaimed majesty but with his ego still intact, Loki faces consequences he never thought could happen to such a supreme being as himself. In that, there is a lot of humor as he is taken down a few pegs and struggles to find his footing in the unforgiving bureaucracy of the Time Variance Authority. As the series progresses, we see different sides of Loki as he is drawn into helping to solve a serious crime with an agent 1 of the TVA, Mobius, who needs his “unique Loki perspective” to locate the culprits and mend the timeline. -

Brevard Live December 2012

Brevard Live December 2012 - 1 2 - Brevard Live December 2012 Brevard Live December 2012 - 3 4 - Brevard Live December 2012 Brevard Live December 2012 - 5 6 - Brevard Live December 2012 Content december 2012 FEATURES page 51 JOE BONAMASSA CHRISTMAS IN BREVARD Columns Since he broke into the blues-rock scene The Christmas season is here and has in the year 2000, Joe Bonamassa has more to offer than shopping bargains! If Charles Van Riper been working hard on his career with in- you want to enjoy the cultural meaning of 22 Political Satire ternational touring and CD releases while Christmas, there are lots of entertaining gaining a lot of fans and accolades. He is performances at our theatres. Calendars a true talent and a protégé. Page 17 & 19 Live Entertainment, Page 11 25 Concerts, Festivals GREAT WHITE MAGNOLIA FEST Nobody here tells you how to live, or Expose Yourself The band hit the mainstream in 1987 by Charles & Lissa when they released Once Bitten..., how to feel; it’s strictly people living 30 within the moment and left to their own which featured the hits “Rock Me” and Brevard Scene “Save Your Love”. accord. Caleb Miller was there to experi- ence the vibe of this annual festival. Steve Keller gives . 33 you the lowdown. Page 11 Page 20 CD Reviews ORIGINAL MUSIC SERIES JESSILYN PARK 39 by John Leach The past 8 weeks have been a huge suc- This story is about a grandmother and her cess and a win-win situation for original granddaughter who became inspired to HarborCityMusic bands and the audience. -

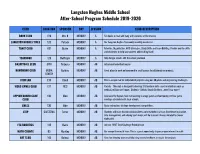

Langston Hughes Middle School After-School Program Schedule 2019-2020

Langston Hughes Middle School After-School Program Schedule 2019-2020 CLUB LOCATION SPONSOR DAY SESSION CLUB DESCRIPTION BOOK CLUB E19 Mrs. K MONDAY A Fun books to read and hang with students of like interest. LANGSTON HUGHES TIMES 128 Pollack MONDAY A Our Langston Hughes Community monthly newsletter. TOAST CLUB H31 Burke MONDAY A Tutorials, Organization, AVID Strategies, Study Skills and Team Building. Provide you the skills and strategies to help you succeed while eating toast! YEARBOOK 123 Hailfinger MONDAY A Help design, create, edit the school yearbook BASKETBALL CLUB GYM DeSouza MONDAY AB Intramural basketball league HOMEWORK CLUB MEDIA Batkins MONDAY AB Great place to work on homework in small groups to collaborate on projects. CENTER STEM LAB E18 Cloud MONDAY AB This is an open lab for independent projects using our 3D prints and engineering challenges. VIDEO GAMES CLUB E17 RCC MONDAY AB Parents - This club is designed to develop 21st century skills used in industries such as medical, military and space. Students- Switch, Smash Brothers ...need I say more? APPIAN BOARD GAME 130 Alire MONDAY AB Sponsored by Appian, have fun learning strategy games and competing in three game CLUB meetups scheduled with local schools. CHESS 130 Alire MONDAY AB Basic instruction, strategy development, competition. STEP CAFETERIA Turner MONDAY AB Students will learn to work collaboratively and creatively in a team. Excellence in practice, time management, and valuing team mates will be stressed. Always imitated but never duplicated. FTC ROBOTICS 145 Davis MONDAY AB Join our FIRST Tech Challenge Robotic team. MATH COUNTS B5 Markley MONDAY AB Our competitive math team. -

Thelondon Link

January - February 2015 Volume 51, Issue 4 The London Link 427 (LONDON) WING — ROYAL CANADIAN AIR FORCE ASSOCIATION 2155 CRUMLIN SIDE ROAD | LONDON, ON N5V 3Z9 | 519-455-0430 | WWW.427WING.COM Our Clock...Found In Reader’s Digest “Our Canada” 427 (London) Wing Member and our Public Relations representative, Don Martin, recently brought in the following article he found while perusing the pages of the November/December edition of the magazine, “Our Canada”. Don assisted the Managing Editor, Gary George, by spreading the word to veteran’s and their families to help fill the pages of this nationally distributed magazine with stories that pay tribute to the men and women of the Canadian Armed Forces. This was a special edition that showcased archival photos and stories that really helped bring the edition to life. They really did a terrific job! Don has a copy of the magazine and if you’re interested in checking out this specific edition, you can find him most Friday’s at the club. Great work, Don! New Years Dance a Smash Hit! The evening of Wednesday, December 31st, 2014 saw a huge turnout of party goers, all looking to ring in the New Year in grand style. The evening had all the bells and whistles, including everyone’s favourite DJ, Dr. Energy Nippy Watson on entertainment and delicious food prepared by Mary Watson, who was also responsible for the planning and execution of the event. Great work, Mary and thank you to all those who volunteered to help out! We would also like to thank all the members and friends of the Wing for coming out that night and celebrating with us! Here are a few pictures from the night! THE LONDON LINK | 1 ROYAL CANADIAN AIR FORCE ASSOCIATION (RCAFA) MISSION STATEMENT The RCAFA is a national aerospace and community service organization to: • Commemorate the noble achievements of the men and women who served as members of Canada’s Air Forces since its inception; • Advocate for a proficient and well equipped Air Force; and, • Support the Royal Canadian Air Cadet program. -

New Look Coming for Lynn Street

TUESDAY, SEPTEMBER 29, 2020 New look coming for Lynn street art By Gayla Cawley Told, the two-week initiative will ways that people could still be of Lynn youth, Wilson said Beyond ITEM STAFF kick off on Oct. 11 and consist of brought together to share stories Walls partnered with a variety of the installation of youth-provid- of what they have been experienc- different groups to help collect the LYNN — Beyond Walls has re- ed art and photography, as well ing in 2020. stories or to create the ability for imagined its annual street art as new artwork created by street “For Lynn youth, they’ve experi- the artwork to be installed. festival this year into a downtown artists incorporating elements of enced an awful lot this year,” said In preparation of the initiative, art-installation project that will stories that have been submitted Wilson. “Times have been scary, which runs through Oct. 24, more be inspired by Lynn’s youth. by the city’s youth, according to Al (they) have been challenging, than 300 photographs, drawings, Unlike past years, where events Wilson, founder and CEO of Be- but none more so than for kids. paintings and stories were sub- that typically draw large crowds yond Walls. The idea is this is a way to show mitted by aspiring artists and were held, the sole focus of this As the COVID-19 pandemic be- that the youth were heard in a writers, ages 5 to 21, which were year’s project will be the large- gan to take shape this spring, it time where it’s really necessary reviewed by a panel of profession- scale murals, art installations became apparent fairly quickly to show inclusion, social justice, al artists, designers, educators Artwork by artist and performances created by a di- that a large-scale street festival opportunity and equity. -

Public Speaking Pdf Free Download

PUBLIC SPEAKING Author: Irvah Lester Winter Number of Pages: 312 pages Published Date: 01 Nov 2003 Publisher: INDYPUBLISH.COM Publication Country: United States Language: English ISBN: 9781414263861 DOWNLOAD: PUBLIC SPEAKING Public Speaking PDF Book Additionally, the book follows the trail of the political economy of Guinness. Acts of Enjoyment: Rhetoric, Zizek, and the Return of the SubjectWhy are today's students not realizing their potential as critical thinkers. What really goes on at SM clubs. com or www. In Jeff's words, "The armor we wear to protect ourselves from the full experience of life does not really protect us--it just keeps us comfortably numb. This scarce antiquarian book is a facsimile reprint of the original. You are led across an alchemical bridge into a secret room of your own. " Â Joseph Kett, Review of American History "What remains solid and permanently useful. And you'll see how you can write your own command-line commands and define new mappings to call them. Every edition is updated with the newest entries from today's manufacturers of handguns, rifles and shotguns, plus the latest values from a wide range of experts, editors and auction houses for virtually every gun made or sold in America since the early 1800s. Thus, a real definition of sustainable supply chain management must take account of all relevant economic, social and environmental issues. Scroll up and click 'add to cart' to secure your copy now. Examwise Volume 2 for 2012 Cfa Level I Certification the Second Candidates Question and Answer Workbook for Chartered Financial Analyst (with Download Practice Exam Software)TEST YOUR READINESS FOR THE 2012 CFA LEVEL 1 EXAM with This QA Workbook with 550 Practice Questions Free Software Download Containing Unlimited Mock Exams The Level I Chartered Financial Analyst exam is well respected and tough, with an average pass rate of only 39. -

Breeze Corp. Announces Expansion 1 .Jhffii

The islands' newspaper of record L, LIBRARY DUNLOP RO "' Jake Fisher Week of June 3 - 9, 2004 SANIBEL & CAPTIVA, FLORIDA VOLUME 31, NUMBER 22, 24 PAGES 75 CENTS County adds high-tech aircraft to Emergency Medical Services fleet By Donna T. Schuman patients can be hooked to all of the moni- Staff Writer toring equipment. Two emergency atten- dants will also be in the aircraft as well as The newest addition to Lee County's a pilot and a co-pilot. The make up of the Emergency Medical Services fleet will emergency personnel is not yet known, not only provide the county with the latest but will consist of some combination of advances in emergency transportation, but nurses, emergency medical technicians also represents a major upgrade to the and paramedics. level of emergency medical services avail- "Having two caregivers on board will able in Lee County. also meet the national standards for emer- The $5.5 million American Eurocopter, gency aircraft transport," O'Neal said. twin engine EC 145 air-ambulance heli- "Ninety-seven percent of EMS helicopters copter, is the first of its kind in the flying in the U.S., have two caregivers in Western Hemisphere. Med Star One, as the back and two in the front. the county calls it, provides the highest "Our plan is to have two caregivers in quality out-of-hospital emergency med- the aircraft at all times. We're also ical care and transportation, officials said. increasing the level of service, we want to The most important difference between be able to provide critical care transport the two aircraft, according to Chief Pilot service. -

THE BRIDGES of MADISON COUNTY Case Study: Donald Holder Lighting Design, Inc.Te Papa Tongarewa

Case Study: Donald Holder Lighting Design, Inc. TONY AWARD WINNER DON HOLDER LIGHTS THE BRIDGES OF MADISON COUNTY Case Study: Donald Holder Lighting Design, Inc.Te Papa Tongarewa Holder lit the cornfield and horizon detail on a translucent sky using backlight reflected fof a bounce drop. For Donald Holder, a two-time Tony Award® winner with As he neared college, Holder was equally passionate about theatre, music, and the outdoors, so he attended The University of Maine, 10 nominations under his belt, there’s nothing more where he majored in forestry while pursuing theatre and music in a exciting than being in the theatre. After all, it’s where vibrant performing arts program. After graduating, he spent three years he gets to reveal the world of a great play or musical as a technical director and lighting designer at Muhlenberg College before earning a master in fine arts from the Yale School of Drama. and help create something special that transports “It was at Yale, under the extraordinary mentorship of Jennifer Tipton, audience members to a magical place, allowing them where I developed a clear understanding of technique and process that would serve as the foundation for my career,” he recalls. to forget their cares for a few hours each night. Today, Holder has one full-time employee at Donald Holder Lighting Design, Inc., and he hires freelancers when needed. About 75% of his It’s a love born from spending his youth seeing Broadway shows, opera, work is in theatre, opera, and dance, and 25% is in other disciplines, ballet, and symphony orchestra performances, and studying violin, tuba, including architecture. -

Vol. 34, No. 2 Winter 2007

Vol. 34, No. 2 TLA’s 70th Anniversary Year Winter 2007 REGISTER NOW FOR TLA'S SECOND SYMPOSIUM ON PERFORMANCE RECLAMATION, Friday, February 16, at NYU. See page 23 for details and information on how to sign-up. Theatre Library Association Presents Registration for the Theatre Library Association Performance Reclamation Symposium Symposium is $75. TLA members and seniors pay $50. American Society for Theatre Research members will receive a one-year TLA membership as part of their The Theatre Library Association (TLA) – in conjunction $75 registration. Full-time students may register for with Mint Theater, New York City Center Encores!, and $25 and receive a complimentary one-year Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival – announces its second membership. Symposium, Performance Reclamation: Research, Discovery, and Interpretation. Martha S. LoMonaco, President of Theatre Library Association, remarks, “After the success of our first Exploring the complex challenges of staging works symposium on Performance Documentation and recovered from dramatic and musical repertories, three Preservation in an Online Environment in 2003, we in-depth case studies of remounting works of drama, wanted to tackle issues of performance reclamation musical theatre, and modern dance will be presented to explore the research library’s unique and proactive on Friday, February 16, 2007 from 9:00 AM – 5:00PM partnership in this exciting process.” at the Kimmel Center for University Life at New York University, 70 Washington Square South at LaGuardia This Theatre Library Association Symposium is Place, New York City. made possible through the generous support of the Gladys Krieble Delmas and Shubert Foundations. Known for excavating buried theatrical treasures, artists For the program schedule: and dramaturgs from Mint Theater, Encores! and http://tla.library.unt.edu/symposiaworkfileindexpage_file Jacob’s Pillow will take the audience on a theatrical dig s/symposiumagenda.htm – rediscovering musical scores, recovered KENNETH SCHLESINGER choreography, and forgotten plays. -

Eastern Tops Enrollment Growth Group Has

Eastern Illinois University The Keep February 2006 2-10-2006 Daily Eastern News: February 10, 2006 Eastern Illinois University Follow this and additional works at: http://thekeep.eiu.edu/den_2006_feb Recommended Citation Eastern Illinois University, "Daily Eastern News: February 10, 2006" (2006). February. 8. http://thekeep.eiu.edu/den_2006_feb/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the 2006 at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in February by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "Tell the truth and don't be afraid. " SECTION + Women fall to fifth with loss: page 12A THE D AILY FRIDAY FEBRUARY 10 2006 Eastern Illinois University, Charleston BIG BROTHERS, BIG SISTERS Eastern tops enrollment growth Group has BY )ACLYN GORSKI 80 volunteer STAFF REPORTER disparity Eastern's smdent population for the spring semester of this year has BY KRISTEN lARSEN seen an increase in student enroll CITY EDITOR ment since last year around this time. Charleston's Big Brothers Big Sisters A 5.3 percent increase brought program is 80 volunteers short for the the enrollment from I0,839 in the I20 children enrolled in the program. spring of 2005 to II ,4I4 this Of the 80 children that are spnng. unmatched, exactly half are from each It is the biggest increase com gender. pared to the changes in smdent "There is almost always a problem in enrollment at Western illinois all the agencies of finding matches for University, the University of Illinois boys," said Marsha Ndoko, program at Urbana-Champaign and Illinois supervisor at Big Brothers Big Sisters of State University.