Enabling Sustainable Livelihoods Through Improved Natural Resource Governance and Economic Diversification in Kono District

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Local Council Ward Boundary Delimitation Report

April 2008 NATIONAL ELECTORAL COMMISSION Sierra Leone Local Council Ward Boundary Delimitation Report Volume One February 2008 This page is intentionally left blank TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword 1 Executive Summary 3 Introduction 5 Stages in the Ward Boundary Delimitation Process 7 Stage One: Establishment of methodology including drafting of regulations 7 Stage Two: Allocation of Local Councils seats to localities 13 Stage Three: Drawing of Boundaries 15 Stage Four: Sensitization of Stakeholders and General Public 16 Stage Five: Implement Ward Boundaries 17 Conclusion 18 APPENDICES A. Database for delimiting wards for the 2008 Local Council Elections 20 B. Methodology for delimiting ward boundaries using GIS technology 21 B1. Brief Explanation of Projection Methodology 22 C. Highest remainder allocation formula for apportioning seats to localities for the Local Council Elections 23 D. List of Tables Allocation of 475 Seats to 19 Local Councils using the highest remainder method 24 25% Population Deviation Range 26 Ward Numbering format 27 Summary Information on Wards 28 E. Local Council Ward Delimitation Maps showing: 81 (i) Wards and Population i (ii) Wards, Chiefdoms and sections EASTERN REGION 1. Kailahun District Council 81 2. Kenema City Council 83 3. Kenema District Council 85 4. Koidu/New Sembehun City Council 87 5. Kono District Council 89 NORTHERN REGION 6. Makeni City Council 91 7. Bombali District Council 93 8. Kambia District Council 95 9. Koinadugu District Council 97 10. Port Loko District Council 99 11. Tonkolili District Council 101 SOUTHERN REGION 12. Bo City Council 103 13. Bo District Council 105 14. Bonthe Municipal Council 107 15. -

Report of the Third General Meeting of the Peace Diamond Alliance 17-18 August 2005 – Koidu, Sierra Leone

REPORT OF THE THIRD GENERAL MEETING OF THE PEACE DIAMOND ALLIANCE 17-18 AUGUST 2005 – KOIDU, SIERRA LEONE AUGUST 2005 This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by [insert Author’s Name(s) here], Management Systems International. REPORT OF THE THIRD ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING OF THE PEACE DIAMOND ALLIANCE 17-18 AUGUST 2005 – KOIDU, SIERRA LEONE Management Systems International Corporate Offices 600 Water Street, SW Washington, DC 20024 Contracted under # 636-a-00-04-00217-00 DISCLAIMER The author’s views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................2 APPENDIX A: LIST OF ATTENDEES (DAY ONE)......................................................9 APPENDIX B: LIST OF ATTENDEES (DAY TWO)...................................................13 APPENDIX C: STATEMENT BY MR. GREGORY A. VAUT, ON BEHALF OF THE US AMBASSADOR...................................................................................17 APPENDIX D: STATEMENT BY MR. MORLAI BAI KAMARA, DEPUTY MINISTER OF MINERAL RESOURCES.............................................................19 APPENDIX E: STATEMENT BY MR. JONATHAN SHARKAH, MINES ENGINEER –KONO.................................................................................................20 APPENDIX F: STATEMENT BY MR. SAHR -

SLEITI Validation Report FINAL 09-08-10

in association with Sierra Leone Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative Validation Report – Final June 2010 CONTENTS A. INTRODUCTION...............................................................................1 1. Background ....................................................................................................................1 2. The importance of EITI in Sierra Leone..........................................................................2 3. Calendar of events for the SLEITI...................................................................................2 B. APPROACH AND METHODOLOGY......................................................5 1. Desk study of key documents ........................................................................................5 2. Consultation with over 60 key stakeholders in Freetown, Kono & Port Loko districts .5 3. Presentation of Initial Findings to the MSG...................................................................6 4. Indicator Judgements.....................................................................................................6 5. A note on terminology ...................................................................................................6 C. PROGRESS AGAINST THE WORK PLAN.................................................7 D. PROGRESS AGAINST VALIDATION INDICATORS.....................................9 1. Has the government issued an unequivocal public statement of its intention to implement EITI?.....................................................................................................................9 -

Sierraleone Local Council Ward Boundary Delimitation Report

NATIONAL ELECTORAL COMMISSION Sierra Leone Local Council Ward Boundary Delimitation Report Volume Two Meets and Bounds April 2008 Table of Contents Preface ii A. Eastern region 1. Kailahun District Council 1 2. Kenema City Council 9 3. Kenema District Council 12 4. Koidu/New Sembehun City Council 22 5. Kono District Council 26 B. Northern Region 1. Makeni City Council 34 2. Bombali District Council 37 3. Kambia District Council 45 4. Koinadugu District Council 51 5. Port Loko District Council 57 6. Tonkolili District Council 66 C. Southern Region 1. Bo City Council 72 2. Bo District Council 75 3. Bonthe Municipal Council 80 4. Bonthe District Council 82 5. Moyamba District Council 86 6. Pujehun District Council 92 D. Western Region 1. Western Area Rural District Council 97 2. Freetown City Council 105 i Preface This part of the report on Electoral Ward Boundaries Delimitation process is a detailed description of each of the 394 Local Council Wards nationwide, comprising of Chiefdoms, Sections, Streets and other prominent features defining ward boundaries. It is the aspect that deals with the legal framework for the approved wards _____________________________ Dr. Christiana A. M Thorpe Chief Electoral Commissioner and Chair ii CONSTITUTIONAL INSTRUMENT No………………………..of 2008 Published: THE LOCAL GOVERNMENT ACT, 2004 (Act No. 1 of 2004) THE KAILAHUN DISTRICT COUNCIL (ESTABLISHMENT OF LOCALITY AND DELIMITATION OF WARDS) Order, 2008 Short title In exercise of the powers conferred upon him by subsection (2) of Section 2 of the Local Government Act, 2004, the President, acting on the recommendation of the Minister of Internal Affairs, Local Government and Rural Development, the Minister of Finance and Economic Development and the National Electoral Commission, hereby makes the following Order:‐ 1. -

Introduction (12 Days– 17 Pages)

From Poverty and War to Prosperity and Peace? Sustainable Livelihoods and Innovation in Governance of Artisanal Diamond Mining in Kono District, Sierra Leone by Estelle Agnes Levin M.A. (Hons) The University of Edinburgh, 1999 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Geography) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA February 2005 © Estelle Agnes Levin, 2005 i Table of Contents Acknowledgements iii. Abstract iv. 1. Introduction 1 2. Methodology and Research Methods 4 2.1 The Sustainable Livelihoods Framework 4 2.1.1 How the World Works - Vulnerability 6 2.1.2 How the World Works - Resiliency 7 2.1.3 How to Effect Change in the World 9 2.2 Designing the Research 11 2.3 The Research Team 12 2.4 Sample Population, Size and Technique 13 2.5 Methods Used 15 2.6 Procedural and Methodological Considerations 17 2.6.1 Process 17 2.6.2 Methodological Considerations 20 3. The Diamond Sector Reform Programme 25 3.1 Actors 25 3.2 Motivations 26 3.3 Objectives 27 3.4 Method 28 3.5 Programme Components and Strategic Themes 32 3.6 Conclusion 36 4. War and Diamonds 37 4.1 Chronology of the War 37 4.2 The Rationale Behind the Sierra Leonean War 40 4.2.1 The informalisation of politics and economy in Sierra Leone: the emergence of the ‘shadow state’ 40 4.2.2 The Lumpenisation and radicalisation of youth 42 4.3 Motivations for War 44 4.3.1 ‘From Mats to Mattresses’: Motivations of the Domestic Fighters 44 4.3.2 Regional and International Actors: Motivations of the facilitators 46 4.4 What did the war have to do with diamonds? 47 4.5 Conclusion 48 5. -

Digging in the Dirt: Child Miners in Sierra Leone's Diamond Industry

Digging in the Dirt: Child Miners in Sierra Leone’s Diamond Industry The International Human Rights Clinic @ Harvard Law School © 2009 International Human Rights Clinic All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 1-56432-469-9 Cover design by Michael Jones 1563 Massachusetts Avenue, Pound Hall 401 Cambridge, MA 02130 • United States of America +1-617-495-9362 • [email protected] http://www.law.harvard.edu/programs/hrp “Digging in the Dirt” Child Miners in Sierra Leone’s Diamond Industry A Report By TablE OF COntEnts EXECUTIVE SUMMARY IV RECOMMENDATIONS IX I. INTRODUCTION: MINING FOR SURVIVAL 1 II. THE PROTEctiON OF ChildrEN UndER DOMEstic and IntErnatiOnal LAW 3 A. Minimum Age Requirements for Hazardous Work B. The Relationship Between the Rights to Health and Education and the Practice of Child Mining C. Protecting Children’s Rights in Post-Conflict Sierra Leone III. AN OvErviEW OF Artisanal DiamOnd Mining 11 A. The Artisanal Diamond Mining Hierarchy: Mining for the Benefit of Few B. Regulatory Agencies: Failed Oversight, Accountability, and Enforcement C. Failures to Adequately Capture Diamond Revenues IV. THE PracticE OF Child Mining 19 A. The Prevalence of Child Mining B. Age of Child Miners C. The Length of Time Children Spend as Miners D. Working Conditions for Child Miners E. Poor Compensation for Child Labourers F. The Impact of Mining on Children’s Health G. How Elder Sibling Responsibilities Drive Children into Mining H. The Exploitation of Girls in Mining Areas I. The Emotional Consequences of Mining on Children V. THE IMPACTS OF THE WAR ON Child Mining 33 A. -

A Sub-National Case Study of Liberal Peacebuilding in Sierra Leone and Liberia

Department of Political Science McGill University Harmonizing Customary Justice with the Rule of Law? A Sub-national Case Study of Liberal Peacebuilding in Sierra Leone and Liberia By Mohamed Sesay A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfilment of requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D.) Mohamed Sesay, 2016 ABSTRACT One of the greatest conundrums facing postwar reconstruction in non-Western countries is the resilience of customary justice systems whose procedural and substantive norms are often inconsistent with international standards. Also, there are concerns that subjecting customary systems to formal regulation may undermine vital conflict resolution mechanisms in these war-torn societies. However, this case study of peacebuilding in Sierra Leone and Liberia finds that primary justice systems interact in complex ways that are both mutually reinforcing and undermining, depending on the particular configuration of institutions, norms, and power in the local sub-national context. In any scenario of formal and informal justice interaction (be it conflictual or cooperative), it matters whether the state justice system is able to deliver accessible, affordable, and credible justice to local populations and whether justice norms are in line with people’s conflict resolution needs, priorities, and expectations. Yet, such interaction between justice institutions and norms is mediated by underlying power dynamics relating to local political authority and access to local resources. These findings were drawn from a six-month fieldwork that included collection of documentary evidence, observation of customary courts, and in-depth interviews with a wide range of stakeholders such as judicial officials, paralegals, traditional authorities, as well as local residents who seek justice in multiple forums. -

Annex A. Programme Proposal

Full Programme Proposal Format Date of submission 30/11/2020 Sierra Leone: Kamara, Gbense, and Soa Benefiting country and location(s) Chiefdoms in Kono District Strengthening Human Security in in the Remote Title of the programme Chiefdoms of Gbense, Soa, and Kamara in Kono District of Sierra Leone. From 01/01/2021 to 31/12/2022 Duration of programme (24 months) Ms. Rokya Ye-Dieng, UNDP Deputy Resident Representative, [email protected] Lead UN organization Mr. Charles Amponsah, Programme Finance Specialist, [email protected] Mrs. Nyabenyi Tito Tipo, Implementing UN organization(s) FAO Representative, Sierra Leone [email protected] African Development Bank, IFAD, World Bank, Non-UN implementing partners Government and Community Partners Resident Coordinator(s) Resident Coordinator’s Office (RCO) Dr. Babatunde Ahonsi (For submissions from regional entities, offices of Resident Coordinator, Sierra Leone SRSGs or other similar entities, submissions can [email protected] be from the highest-ranking UN official) Total programme budget including indirect support costs in US$ (UNTFHS and other $4,309,383 sources of funding) Amount requested from the UNTFHS in US$ (no more than $2million for operational $1,010,823 programmes and no more than $300,000 for outreach/advocacy programmes) Amount to be sourced from other donors in African Development Bank: $1,838,000 IFAD: $838,560 US$ (please list each donor and the amount to be World Bank: $220,000 contributed) Community In-Kind: $402,000 Target SDG(s): SDGs 1,2,5,6,8,15 and 16 1 1. Executive summary This joint programme (JP) uses the Human Security Approach to address development challenges and vulnerabilities in three chiefdom areas of Kono District of Sierra Leone. -

NEWSLETTER September 2018 | Vol

AGAINST ALL ODDS… SEND Sierra Leone NEWSLETTER September 2018 | Vol. 2 No. 6 www.sendwestafrica.org Overcoming Social & Cultural Barriers to Political & Economic Empowerment! Against all odds…Overcoming social and cultural barriers to political and economic empowerment! Contents Foreword………………………………………………………………………………………............................3 Profiles: Aminata Rogers………………………………………………………………………………………………….4 Alice B. D. Rogers……………………………………………………………………………………………….5 Baby Salay Nyomeh……………………………………………………………………………………………..6 Abibatu Farma…………………………………………………………………………………………………..7 Aminata Koroma………………………………………………………………………………………………..8 Massah Bockarie………………………………………………………………………………………………..9 Fatmata Njaiga…………………………………………………………………………………………………10 Rosemarie Fatorma……………………………………………………………………………………………11 Salaymatu Sheriff……………………………………………………………………………………………...12 Esther N. Kasaimba……………………………………………………………………………………………13 Mariama M. Tarawally………………………………………………………………………………………..14 Amie F. Jimmy…………………………………………………………………………………………………15 Nancy Coomber………………………………………………………………………………………………..16 Edith Amara……………………………………………………………………………………………………17 Jamie Kpange………………………………………………………………………………………………….18 Kona Messi Duwai……………………………………………………………………………………………..19 Doris Baby Momoh…………………………………………………………………………………………….20 Mariama Kandeh………………………………………………………………………………………………21 Juliet Kumba Mambu…………………………………………………………………………………………22 Adama Jalloh…………………………………………………………………………………………………..23 Kumba Nyandemoh……………………………………………………………………………………………24 Sia Elenor Ngegba……………………………………………………………………………………………..25 -

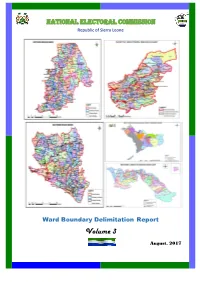

2017 Ward Description, Maps and Population

NATIONAL ELECTORAL COMMISSION Republic of Sierra Leone Ward Boundary Delimitation Report Volume 3 August, 2017 Foreword The National Electoral Commission (NEC) is submitting this report on the delimitation of constituency and ward boundaries in adherence to its constitutional mandate to delimit electoral constituency and ward boundaries, to be done “not less than five years and not more than seven years”; and complying with the timeline as stipulated in the NEC Electoral Calendar (2015-2019). The report is subject to Parliamentary approval, as enshrined in the 1991 Constitution of Sierra Leone (Act No 6 of 1991); which inter alia states delimitation of electoral boundaries to be done by NEC, while Section 38 (1) empowers the Commission to divide the country into constituencies for the purpose of electing Members of Parliament (MPs) using Single Member First- Past –the Post (FPTP) system. The Local Government Act of 2004, Part 1 –preliminary, assigns the task of drawing wards to NEC; while the Public Elections Act, 2012 (Section 14, sub-sections 1 &2) forms the legal basis for the allocation of council seats and delimitation of wards in Sierra Leone. The Commission appreciates the level of technical assistance, collaboration and cooperation it received from Statistics Sierra Leone (SSL), the Boundary Delimitation Technical Committee (BDTC), the Boundary Delimitation Monitoring Committee (BDMC), donor partners, line Ministries, Departments and Agencies and other key actors in the boundary delimitation exercise. The hiring of a Consultant, Dr Lisa Handley, an internationally renowned Boundary delimitation expert, added credence and credibility to the process as she provided professional advice which assisted in maintaining international standards and best practices. -

FINAL Thesis

Foundational hybridity and its reproduction hybridity and its reproduction Foundational copenhagen business school handelshøjskolen solbjerg plads 3 dk-2000 frederiksberg danmark www.cbs.dk Foundational hybridity and its reproduction Security sector reform in Sierra Leone Peter Alexander Albrecht PhD Series 33.2012 ISSN 0906-6934 Print ISBN: 978-87-92842-92-3 Doctoral School of Organisation Online ISBN: 978-87-92842-93-0 and Management Studies PhD Series 33.2012 FOUNDATIONAL HYBRIDITY AND ITS REPRODUCTION Security sector reform in Sierra Leone Peter Alexander Albrecht PhD Dissertation, June 2012 Copenhagen Business School, Department of Business and Politics Primary supervisor: Professor Anna Leander (CBS) Secondary supervisor: Senior Researcher Lars Buur (DIIS) Peter Alexander Albrecht Foundational hybridity and its reproduction Security sector reform in Sierra Leone 1st edition 2012 PhD Series 33.2012 © The Author ISSN 0906-6934 Print ISBN: 978-87-92842-92-3 Online ISBN: 978-87-92842-93-0 The Doctoral School of Organisation and Management Studies (OMS) is an interdisciplinary research environment at Copenhagen Business School for PhD students working on theoretical and empirical themes related to the organisation and management of private, public and voluntary organizations. All rights reserved. No parts of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. -

The Alluvial Diamond Mining Ordinance, 1956

Alluvial Diamond Mining [Cap. 198 1753 CHAPTER 198. ALLUVIAL DIAMOND MINING. P.N. LICENSED DIAMOND MINING AREAS 34 of 1957. declared by the Minister to be such, under sub-section 3 ( 1). 50 of 1957. 81 of 1957. 116 of 1958. 59 of 1959. 138 of 1959. 152 of 1959. 154 of 1959. 1. This Declaration may be cited as the Alluvial Diamond Citation. Mining (Licensed Diamond Mining Areas) Declaration. 2. The chiefdoms or parts of chiefdoms listed in the Schedule Declaration. are hereby declared to be licensed alluvial diamond mining areas with effect from the dates stated in the said schedule. SCHEDULE. 1. The following chiefdoms of the Bo District, with effect from the 6th day of February, 1956- BAOMA, BuMPE, JAIAMA-BoNGo, LuBu, TrKONKO. 2. The following chiefdoms of the Kenema District, with effect from the 6th day of February, 1956- KANDU-LEPPIAMA, SIMBARU, WANDO. 3. The following chiefdoms of the Bo District, with effect from the 1st day of March, 1956- BADJA, KAKUA, KoMBOYA. 4. The following chiefdoms of the Kenema District, with effect from the 1st day of March, 1956- GoRAMA MENDE, NoNGOWA, SMALL Bo. 5. The DAMA Chiefdom of the Kenema District, with effect from the 11th day of June, 1956. 6. The following part of the LowER BAMBARA Chiefdom in the Kenema District, with effect from the 28th day of March, 1957- ALL THA'rPARCEL OF LAND of the LowER BAMBARA Chiefdom in the Kenema District of the South-eastern Province of the Protectorate of Sierra Leone the boundary whereof commencing at a point which is on a true bearing of 119° 30' and a distance of 10,000 feet approximately from Panguma Town and which is the centre of the Panguma-Kenema Motor Road bridge over the River Tongo and which is also Point Number 3 of Mining Lease 2001 and thence in a southerly direction following the East gutter of the Panguma-Kenema road for a distance of apProximately 3·7 miles to Point Number 4 of Mining Lease 2001 and 1754 Cap.