Topography and Settlement Jan Broadway & Alex Craven with James Hodsdon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Arts Development Strategy for Cheltenham 2004/5 to 2006/7

Appendix B Cheltenham Borough Council Access & excellence: an arts development strategy for Cheltenham 2004/5 to 2006/7 Draft 6 10 March 2004 Index 1. Introduction 4 2. Methodology 4 3. A definition of the arts 5 4. Why are the arts important? 5 4.1 The social impact of the arts 4.2 The economic impact of the arts 4.3 The arts and planning 4.4 The arts and crime & disorder 4.5 Arts in health 5. Strategic framework 8 5.1 Department of Culture Media and Sport 5.2 Arts Council England, South West 5.3 Gloucestershire County Council 6. Local context – how does this strategy relate to corporate priorities? 10 6.1 ‘Never a Dull Moment’ – Cheltenham’s Cultural Strategy 2002 to 2006 6.2 ‘Our Future Our Choice’ - The Community Plan 6.3 Business Plan 6.4 Civic Pride 6.5 Draft night time economy strategy 6.6 Economic development and regeneration strategy 6.7 Other 7. The arts in Cheltenham 13 7.1 Professional arts activity 13 7.1.1 Cheltenham Art Gallery and Museum 7.1.2 Everyman Theatre 7.1.3 Cheltenham Arts Festivals Limited 7.1.4 Town Hall and Pittville Pump Room 7.1.5 The Holst Birthplace Museum 7.2 Non-professional arts activity 16 7.2.1 The Playhouse 7.2.2 Cheltenham Arts Council 7.3 The arts and education 17 7.4 Education, outreach and community arts initiatives 18 7.4.1 Cheltenham Arts Festivals Limited 7.4.2 The Everyman 7.4.3 Cheltenham Art Gallery & Museum 7.4.4 The Holst Birthplace Museum 8. -

Cheltenham Local History Society Donated Books for Sale: Summer 2021

Cheltenham Local History Society Donated Books for sale: Summer 2021 Cheltenham – pages 1-10 Charlton Kings – page 11 Leckhampton & Swindon – page 12 Cotswolds – pages 13-14 Gloucestershire – pages 15-24 England & Wales – pages 25-27 Scotland, Ireland, Britain & General – pages 27-30 Cheltenham Cheltenham Local History Society Journal Single copies, unless noted, of the following issues are available, all paperback, variously bound, in good to very good condition, sometimes with name/address stickers; various numbers of pages. 3 (1985) [0030]; 10 (1993-94) [0038]; 12 (1995-96) [0039]; 15 (1999) [0040] Price per copy £1.00 17 (2001) [0487]; 18 (2002) [0042] [0488] two copies; 19 (2003) [0489]; 20 (2004) [0490]; 21 (2005) [0491]; 22 (2006) [0045]; 23 (2007) [0492]; 24 (2008) [0047] [0048] [0049] [0493] four copies; 25 (2009) [0494]; 27 (2011) [0053] [0495] two copies; 28 (2012) [0055] [0496] two copies; 29 (2013) [0497]; 31 (2015) [0058] [0059] two copies; 32 (2016) [0060]; 33 (2017) [0061]; 34 (2018) [0062] Price per copy £2.00 Cheltenham Local History Society Chronologies Single copies, unless noted, of the following issues are available, all paperback, variously bound, in good to very good condition, sometimes with name/address stickers; various numbers of pages. Waller, Jill, compiler; A Chronology of Trade and Industry in Cheltenham (2002) [iv] + 36 pp, b&w illus; spiral bound. [0063] £2.50 Waller, Jill, compiler; A Chronology of Sickness and Health in Cheltenham (2003) ii + 36 pp, b&w illus; spiral bound. [0064] £2.50 Waller, Jill, compiler; A Chronology of Crime and Conflict in Cheltenham (2004) [ii] + 38 pp, b&w illus. -

Glenmore Lodge

GLENMORE LODGE CHELTENHAM • GLOUCESTERSHIRE GLENMORE LODGE WELLINGTON SQUARE, CHELTENHAM, GLOUCESTERSHIRE An elegant Grade II Listed villa of major historic significance Entrance Hall, Reception Hall, Drawing Room, Dining Room, Kitchen/Breakfast/Family Room, Utility Room, Laundry Room, Cloakroom, Separate WC, Conservatory. Master Bedroom with En Suite Bathroom & Dressing Room, Three Further Bedroom Suites. Lower Ground Floor Comprising: Library, Office, Games Room, Kitchen, Bedroom with En Suite Bathroom, Lobby, Hot Tub Room, Sauna. Gardener’s WC. Boiler Room. Three Under Pavement Storage Vaults. Off Road Parking for Several Cars. Two Garages. Beautifully Landscaped Gardens to Front & Rear. Planning Permission for a Detached Two Bedroom Single Storey Dwelling. Chris Jarrett Savills Cheltenham Imperial Square, Cheltenham Gloucestershire, GL50 1PZ Tel: 01242 548 000 [email protected] savills.co.uk Your attention is drawn to the important notice on the last page of the text 3 Situation Wellington Square is one of Cheltenham’s finest squares, being As well as superb educational facilities the town is well known within walking distance of the town centre, Pittville Park and lakes for the many literary and music festivals that it holds, as well as and the historic Pittville Pump Room. the Cheltenham Racecourse, cricket and National Hunt festivals. Cheltenham became a spa town in 1716, although its popularity Sporting opportunities within walking distance include squash, flourished after King George III visited in 1788. Its heyday as a tennis and swimming facilities whilst there are also a number of golf spa town was to last from about 1790 to 1840 and it was during courses on the edge of the town. -

Pittville Park

Pittville Park Green Flag Award and Green Heritage Site Management Plan 2016 – 2026 Reviewed January 2020 1 2 Contents 1.0 Introduction .............................................................................................................................................. 5 2.0 General information about the park .......................................................................................................... 8 2.1 Legal Issues ................................................................................................................................................... 8 2.2 Strategic Significance of Pittville Park ........................................................................................................ 10 2.3 Surveys and Assessments undertaken ........................................................................................................ 13 2.4 Community Involvement ............................................................................................................................ 13 2.5 Current management structure .................................................................................................................. 15 3.0 Historical Development............................................................................................................................ 18 3.1 The heritage importance of the park .......................................................................................................... 18 3.2 History of the park - timeline ..................................................................................................................... -

Leading Through the Worst Storm, Weathering the Crisis and Having the Resilience to Rebuild

Leading Through the Worst Storm, Weathering the Crisis and having the Resilience to Rebuild C2S asked Laurie Bell, CEO The Cheltenham Trust about their Covid story, lessons learnt and what good leadership looks like. n 5 March 2018, Salisbury hit headlines across the world following the unprecedented Osituation after a former Russian spy and The pessimist his daughter were poisoned by Novichok nerve agent in its city centre. Overnight complains a city reliant on tourists and visitors saw its local economy crash. A city renowned about the wind. The for its cathedral and quintessential streets and shops was abandoned by optimist expects it to tourists and visitors avoiding its centre though fear of the nerve agent. This high change. The leader profile situation hit local, national and international news and became a fast adjusts the sails. moving, highly sensitive and political situation. Communication was vital to John Maxwell provide facts, reassurance and guidance Laurie Bell, CEO The Cheltenham Trust and to encourage a return to normality and recovery. Leading through a major crisis is The Cheltenham Trust is an independent organisation and deliver growth and a something we never expect in a career charity that manages Cheltenham’s sustainable future. A five-year plan focused lifetime. While we can set out plans and most iconic venues; Pittville Pump Room, on business growth in all venues and a contingencies for managing in a crisis, Cheltenham Town Hall, The Wilson significant programme of change was the reality is very different, and I speak Museum and Art Gallery, Leisure at approved at the end of 2019. -

Berky Enrichment Imaginative, Inspiring and Fun! Spring Concerts Berky Pupils Pull out All the Stops History Mystery Year 2 Solve Clues to Become Knights!

2019 SPRING MAGAZINE SCHOOL B ERKHAMPSTEAD TERM Berky enrichment IMAGINATIVE, INSPIRING AND FUN! Spring concerts BERKY PUPILS PULL OUT ALL THE STOPS History Mystery YEAR 2 SOLVE CLUES TO BECOME KNIGHTS! INSIDE: HELEN Gill’s BALLET CLASSES | CHESS SUCCESS | SPOTLIGHT ON CERYS MCCREANOR Thoughts from Spotlight on THE HEAD CERYS MCCREANOR Glance through this edition of the Berky Blazer and you’ll see evidence Mme McCreanor is our specialist language of creative teaching and a passion for learning... everywhere! teacher. She joined Berky in October 2016 and The staff offer such a wide range of wonderful opportunities for the teaches French to every pupil in the School. children... from the chicks in Kindergarten, to adventures in space in She also teaches Spanish to the Year 5s and 6s Reception, to Superheroes in Year 1, the wonderful History Mystery and manages to sneak in a few other languages Day in Year 2 with its code-breaking, research and sleuthing challenges on special days too. Mme McCreanor is a Year (and allowing me to dress up as King Richard). In Prep, the range of 3 form teacher, responsible for the U9 girls’ opportunities has included the annual 500 Word Story Competition, the games teams and also teaches mindfulness Commandery History trip, the House Pancake Races, football, netball and during Carousel. cross-country fixtures - as well as the very successful Chess fixtures and Here, some of her form ask the questions Congress and the wonderful Spring Concert. they’ve always wanted to know... Our magical Spring Concerts, held at the Pittville Pump Room, once Have you always been a teacher? again showed that Music is at the heart of Berkhampstead. -

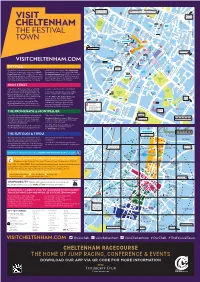

Cheltenham Racecourse (Map Ref E1) the Everyman Theatre (Map Ref D4) D H M B E Lk R S a Park Priory Th D Ed

n Tesco t e A4019 to Tewkesbury, t e e Y d r n l R e Pittville Pump Room, Leisure at Cheltenham, W d M5 North Junction 10, a e U r a EL R d L t L b B I l R T S Racecourse, Park & Ride and A435 to Evesham N G M Gallagher Retail Park ’s D T S D l s O A E D R ’ A N R R ER u l RO P T a u O A S h k D E P a R n C Y t c t U t P r i B4632 to A t e w O S t o w L e e C M a G S s r la d A W N t r L Winchcombe n e e e A 4 r n R 0 E u S S c e t u q e H l 1 L r y u l n & Broadway 9 S n a S i e O S B e r PO W l e e v d IN l E l t D t D O a v t a A e N C V i O n A l E R a M e O r P R r A u en Y t t D n ce R Winston D o R S e o BU s ad T M H g e PITTVILLE Churchill I r n ES a G n t P H i o PR r S o CIRCUS k Memorial S K t T t s M r e T ’ E t e R l S Holst t E l S Gardens E u s a e ’ t E R t r a Birthplace n r t T e e e P T S g e e e S Trinity Museum d t t r c t r n t S S o t a Long Millbrook l D S o S e S The Church q t e P Stay r r N Roundabout e i G a e t t h u v Brewery A Se h t t t n lki H B S L rk S o s S e r a B tre r i e et o n Quarter d o T L lm n r r e n R on G o o n g N y t e i o R y v f a t d G All Saints t e n O i len b e x s S t f W a n al o H s e T P i e Y l S t O t w o tre Church a u D et a g M r e rk e r S re Citizens S o t y n St t P r a T r St w B s A Warwick t e e S a n C N y s R S D Advice n o S e h t a h G Place d s W a & A h e A m g P t e R a o a e r E e n y t o St James’ r J n c T l r O K e i s o ’S d t b n a o e R R R n n n o l d O n o e a W s Roundabout p e N A e p m a r n R P n D b e n l r r S R k Chester e a C r t d o A H l -

2020Venue Guide

2020 VENUE GUIDE meetincheltenham.co.uk EVENT PLANNING MEET IN CHELTENHAM 2020 Meet in Cheltenham can help you with a range of services when planning your Cheltenham is a large Regency spa town located on the edge of the Cotswolds and event. Whether you are looking to organise a large conference over a number in the county of Gloucestershire, giving you easy access to Wales, the Midlands and of days, a one-off bespoke event or a small meeting we’re here to help. London. We’re just an hour away from hubs like Birmingham, Bristol, Cardiff and Oxford, and London is just over two hours’ away by train. Working with over 20 hotels, unique venues and event suppliers in Cheltenham and the surrounding area we provide a free to use venue finding service and specialise With direct access to major motorways, including the M4 and M5, plus mainline in providing competitive venue options and practical destination support. railway stations and international airports, Cheltenham is easily accessible whether you’re travelling by road, rail or air. We can also negotiate bedroom rates at residential properties for bookings of 20 or more people. We can reserve the required accommodation and provide an As the home of GCHQ, Cheltenham is at the centre of the UK’s Cyber Tech industry. easy to use link in order to manage delegate room bookings online. Cheltenham is also known as ‘The Festival Town’, testament to its vibrant cultural offer and year-round calendar of major festivals and events. In addition to venue and accommodation finding we also provide the following -

Statement of Accounts 2015-2016

STATEMENT OF ACCOUNTS 2015/16 CHELTENHAM BOROUGH COUNCIL Statement of Accounts 2015/16 CHELTENHAM BOROUGH COUNCIL 1 STATEMENT OF ACCOUNTS 2015/16 CONTENTS Page(s) 3 - 14 Narrative Report 15 Statement of Responsibilities for the Statement of Accounts 16 Comprehensive Income and Expenditure Statement 17 Balance Sheet 18 Movement in Reserves Statement 19 Cash Flow Statement 20 – 84 Notes to the Accounts 85 – 87 Collection Fund and Notes 88 – 99 Group Accounts and Notes 100 - 104 Housing Revenue Account and Notes 105 - 108 Glossary of Terms 109 - 119 Annual Governance Statement including Statement on the System of Internal Financial Control 120 – 122 Draft Independent Auditor’s Report CHELTENHAM BOROUGH COUNCIL 2 STATEMENT OF ACCOUNTS 2015/16 NARRATIVE REPORT AN INTRODUCTION TO CHELTENHAM BOROUGH COUNCIL Cheltenham is one of Britain’s finest spa towns, set in a sheltered position between the rolling Cotswold Hills and the Severn Vale. It has a population of 115,600 (2011 mid-year census based population estimate) and with its architectural heritage, educational facilities and quality environment, Cheltenham is an attractive place to live, work and play. Cheltenham is home to a number of festivals that take place throughout the year which include the world- renowned Jazz, Music, Science and Literature Festivals. Cheltenham Racecourse hosts sixteen days of racing over 8 events every year including the Gold Cup Festival. The borough also plays host to the Everyman Theatre, the Playhouse Theatre and Cheltenham Town Hall, all of which offer a rich and varied programme of professional and amateur performing arts. It is also home of The Wilson art gallery and museum, hosting a wide range of collections, exhibitions and cultural events. -

RENOVATION of PITTVILLE PUMP ROOM and ITS REOPENING by Ashley Rossiter

Reprinted from Gloucestershire History No. 17 (2003) pages 16-20 RENOVATION OF PITTVILLE PUMP ROOM AND ITS REOPENING By Ashley Rossiter The Pittville Pump Room stands today as a the upper floor as officers’ accommodation. The monument of regency splendour, unquestionably Borough Surveyor was instructed by the Parks and one of Cheltenham’s most beautiful buildings. It was Recreation Grounds Committee to keep records of constructed between 1825-30 as the centrepiece of the condition of the building whilst it was in military what was supposed to be a magnificent estate hands. However, the military authorities during their financed by the minor local politician and occupation refused to allow periodical inspections speculative property developer Joseph Pitt.‘ In a and when eventually an inspection was allowed it town famous across England for its spa waters, was limited in its detail. His first report on the 9"‘ Pittville was the most ambitious and exclusive venue March 1942 noted that the surfacing in front of the for sampling the waters. It had been planned as a U- Pump Room was worn and in places was showing shape of Grecian villas with the Pump Room as its signs of disintegration. Also, the portico on each focal point, serving in its traditional role as a spa as side was walled in with brickwork to offer more well as a community centre. However as the 19th storage accommodation and some stone columns century continued the demand for spa water had been chipped at their bases from collision with decreased. The Pump Room no longer generated as the tailboards of lorries unloading supplies.7 At this much interest or revenue as in its heyday. -

CHELTENHAM Business Guide and Directory

CHELTENHAM Business Guide and Directory www.cheltenham.gov.uk Search 100s of local businesses online at www.cheltenham.gov.uk/business 05.01.16 260mm ROP 3036359 1st 180mm Illustrator CS2 CHE_308300 LH Full Colour Yes READER’S NOTE: CONTACT DETAILS - SHOULD THE COMPANY NAME BEFORE THE MBD_Chelt_Business_guide_Jan16_LayoutADDRESS INCLUDE BUGATTI? 1 22/12/2015 09:29 PLEASE Page 1 ADVISE. MANY THANKS. MESSIER-BUGATTI-DOWTY BUILT-TO-ENDURE Messier-Bugatti-Dowty, a Safran group company, is the world leader in the design, development, manufacture and support of aircraft landing and braking systems. The company supplies innovative landing gear solutions to 30 leading commercial, military, business and regional aircraft manufacturers. We support more than 24,000 aircraft in-service, making over 40,000 landings every day. The company employs 7,000 sta worldwide in locations across Europe, North America and Asia, including a team of 1,200 people in Gloucester at the company’s UK landing gear production and repair facilities. The Gloucester facility has been at the forefront of landing gear technology for over 80 years, dating from the innovative designs of Sir George Dowty to the advanced landing gears for the world’s most modern aircraft. Messier-Dowty Ltd, Cheltenham Road, Gloucester, GL2 9QH Tel: 01452 712424 www.safranmbd.com 3036359 02.02.16 260mm Facing Intro 3036353 1st 180mm Illustrator CS2 CHE_308300 KA Full Colour Yes www.langleywellington.co.uk www.cotswoldconveyancingcentre.co.uk Gloucester: Royal House, 60 Bruton Way, Gloucester, GL1 -

The Aliens Visit Berky

The BBERKHAMPSTEAD SClHOOaL MAGAZIzNE er SPRING 2014 Aliens Visit Berky Inside: House Pancake Races History Mystery Time Science Orchestra Regular features: Music Notes Staff on the Spot Sports Reports Trips and Visits N EWS N EWS STAFF ON THE SPOT Science Headmaster’s News Bethan Evans is our ulfilment comes from many more things than fabulous new Head of Chess Mates doing well in tests. A real education fulfils English and Drama who Orchestra Tunes Fand is about so much more than national joined us in September curriculum results, spelling ages, verbal reasoning and has made quite an scores and the like – we do very well in these but impact already! Up! they aren’t what matters most. A Berkhampstead You have done two terms at Berky – what education is broad, it involves and engages were the highlights? children across a range of areas. It helps them to The Spring Concert and grow into accomplished young people with many the Pancake Races, the strings to their bows and with the right attitude to 500 word story - the embrace life’s challenges. Fulfilment can come from completing a science enthusiasm and commitment of all the children - and the stories written were The Berky chess team can look back with some project successfully, solving maths problems collaboratively, playing sport fantastic to read. satisfaction on the season although it just missed out on league for the school, singing one’s heart out in a gospel choir session - with Berky puddings – iced buns or cherry and cup honours. A record of P10, W8, D1, L1 is more than actions (see below), being part of a team, solving a history mystery, crumble? encouraging and we have plenty of promising players waiting in discovering something about life for The pear and chocolate crumble! the wings.