In Conversation with Claudia Hart

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Brenna Murphy [email protected]

Brenna Murphy www.bmruernpnhay.com www.mshr.info [email protected] Art Collectives Oregon Painting Society, 2007-2011 MSHR, 2011 - present Education BFA, General Fine Arts, Pacific Northwest College of Art, 2009. Awards Fotomuseum Winterthur Post-Photography Prize, 2016 RACC Innovative Art and Technology Award, 2016 RACC Project Grant, 2016 Oregon Arts Fellowship, 2015 Rhizome Commission Recipient, 2012-2013 Publications Domain~Lattice, Pleasure Editions, 2015 Centrl~Lattice Sequence, Onestar Press, 2014 Skyface~SensrMap, Floating World Comics, 2012 Press “Market for Virtual Reality Art gets Tested at Moving Image Fair,” Bryan Boucher, Artnet, 2/2017 “The Architecture of Consciousness: An Interview with Brenna Murphy,” Penny Rafferty, Berlin Art Link, 10/2016. “Alien Yearbook Report,” John Chiaverina, ArtNews, 10/2015. “All Watched Over,” Andrianna Campbell, Art Forum, 7/2015. “High-Tech Mysticism: An Interview with Brenna Murphy,” Tim Gentles, Art in America, 11/2014. “Brenna Murphy: yoni-shaped synths and tribal treasures,” Kate Neave, Dazed, Aug, 2014. “Hyper Object, Brenna Murphy meditates on digital ruins,” Francesco Spampinato, DAMn°,2014 “Expanded Internet Art and the Informational Millieu,” Ceci Moss, Rhizome, 12/2013. "Brenna Murphy presents familiar yet strange installation," John Motley, The Oregonian,10/2013 "Brenna Murphy at Upfor," Jeff Jahn, PORT, Oct 2013. "Brenna Murphy: The archaeologist of meditation," Matt Stangel, Oregon Arts Watch, Oct 2013. "Superare il meccanicismo," Marco Tagliafierro, Flash Art, March 2012. "Brenna Murphy and The Future," Ali Fitzgerald, Art 21 Blog, March 2012. "Artist Profile," Ian Glover, Rhizome, Sept 2011. "Gifs Gone Wild," Francesca Gavin. Oyster Magazine. May, 2011. “HyperJunk- NetArt out of the Past,” Nicolas O’Brien. -

DIGITAL ART and FEMINISM: a SURREAL RELATIONSHIP Anne Swartz Provided Byhumanitiescommons Brought Toyouby

10 Anne Swartz View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Humanities Commons DIGITAL ART AND FEMINISM: A SURREAL RELATIONSHIP SURREAL A AND FEMINISM: ART DIGITAL DIGITAL ART AND FEMINISM: A SURREAL RELATIONSHIP Anne Swartz Many of the images in this exhibition reveal similar interests, themes, and aesthetics to those seen in feminist Art.1 The artists— (PLOLD)RUVWUHXWHU-HQQLIHU+DOO&ODXGLD+DUW<DHO.DQDUHN-HDQHWWH/RXLH5DQX0XNKHUMHH0DU\%DWHV1HXEDXHU0DULH Sivak, Camille Utterback, Adrianne Wortzel, and Janet Zweig—rely on technology as a tool to explore geopolitics, geological phenomenon, obsolete media, data streams and sets, illusion, shifting identities, phantasmagorias, eroticism, bodies, landscapes, geography, and memory. They are not afraid to confront assumptions or propaganda, even challenging conventions and traditions. They show us diverse, alternate domains and generate narratives of augmented worlds. Common to their artworks is the surreal, employed innovatively and underscored by the radical politics of feminism to change society in order to advance it. It is a kind of new romanticism where the real is meshed with fantasy so that the boundaries between the two dissolve. These artists have created pieces that require the viewer’s time; scanning and experiencing the entirety of their respective works over time transports one to their wild and imagined realms. It is easy to lose one’s bearings with these works because they rely upon mysterious disorientation to the viewer’s prosaic and commonplace experiences. It is a situation that is wholly based on the personal, which has been one of the cornerstone themes of feminist art. -

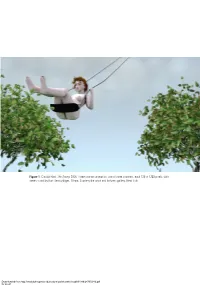

Figure 1 Claudia Hart, the Swing, 2006. Three-Channel Animation, One of Three Channels, Each 720 £ 1280 Pixels, with Stereo Sound by Kurt Hentschla¨Ger, 10 Min

Figure 1 Claudia Hart, The Swing, 2006. Three-channel animation, one of three channels, each 720 £ 1280 pixels, with stereo sound by Kurt Hentschla¨ger, 10 min. Courtesy the artist and bitforms gallery, New York Downloaded from http://read.dukeupress.edu/cultural-politics/article-pdf/9/1/86/247059/86.pdf by guest on 01 October 2021 BEGINNING and END GAMES A Parable in 3D Claudia Hart or many years, I was primarily a painter, and I exhibited F paintings, objects, and photographs in the contemporary art context, first in New York beginning in 1988 and later in Berlin. Then in the late 1990s, I began working with three-dimensional, or 3D, computer imaging for the first time. In the mid-1990s, 3D animation software, or Maya, as it is called, was not available for the personal computer. It was supported exclusively on the UNIX operating system, typically available only in large corporations or academic institutions. So in 1997 I began taking classes at New York University’s Center for Advanced Digital Applications in order to gain access both to Maya and to the center’s sophisticated computer labs. Learning 3D animation was quite challenging, and although I was an early adopter of computers, nothing I had previously done prepared me for the mathematical and technical rigor of spatial 3D imaging or the culture that surrounded it. When it came to courses in Maya or virtual reality simulations, there were hardly any women enrolled in classes. I was also one of only a small coterie of contemporary artists working with this software, since, until recently, 3D animation and imaging existed completely outside the purview of contemporary art discourse. -

John Dogg Pseudonym Used by Richard Prince (B

This document was updated on January 5, 2021. For reference only and not for purposes of publication. For more information, please contact the gallery. John Dogg Pseudonym used by Richard Prince (b. 1947, Panama Canal Zone), active 1986 – present. EDUCATION University of Minnesota (Painting and Philosophy) New York University SELECTED PUBLIC COLLECTIONS The DESTE Foundation of Contemporary Art, Athens MAMCO, Geneva The Rubell Family Collection, Miami The Whitney Museum of American Art, New York SOLO + GROUP EXHIBITIONS 2018 Brand New: Art and Commodity in the 1980s, cur. Gianni Jetzer, Hirshhorn Museum, Washington, D.C. The Conditions of Being Art: Pat Hearn Gallery & American Fine Arts, Co. (1983-2004), Hessel Museum of Art, Annandale-on-Hudson, New York IT’S PERSONAL, Edward Ressle, New York 2017 They say, where there’s smoke, there’s fire, Bern, Kunsthalle Bern, in collaboration with Kunsthaus Glarus, Glarus, Switzerland Répliques: L’Original à L’Épreuve de L’Art: Autour de la Collection d’Olivier Mosset, Musée Des BeauX-Arts, La ChauX-de-Fonds, Switzerland Fictional Artists, Musée d’Art Moderne et Contemporain (MAMCO), Geneva, Switzerland 2016 La Collection Thea Westreich et Ethan Wagner, Centre George Pompidou, Paris 2015 Collected by Thea Westreich Wagner and Ethan Wagner The Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; traveled to Centre George Pompidou 2014 Beg Borrow and Steal, Rubell Family Collection, Miami, Florida 2013 DANNY McDONALD as MINDY VALE in MINDY VALE GOES TO ENGLAND to uncover the 980 MADISON AVENUE NEW YORK, NY 10075 -

Assessment and Treatment of Patients with Suicidal Behaviors

PRACTICE GUIDELINE FOR THE Assessment and Treatment of Patients With Suicidal Behaviors WORK GROUP ON SUICIDAL BEHAVIORS Douglas G. Jacobs, M.D., Chair Ross J. Baldessarini, M.D. Yeates Conwell, M.D. Jan A. Fawcett, M.D. Leslie Horton, M.D., Ph.D. Herbert Meltzer, M.D. Cynthia R. Pfeffer, M.D. Robert I. Simon, M.D. Originally published in November 2003. This guideline is more than 5 years old and has not yet been updated to ensure that it reflects current knowledge and practice. In accordance with national standards, including those of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s National Guideline Clearinghouse (http://www.guideline.gov/), this guideline can no longer be assumed to be current. 1 AMERICAN PSYCHIATRIC ASSOCIATION STEERING COMMITTEE ON PRACTICE GUIDELINES John S. McIntyre, M.D., Chair Sara C. Charles, M.D., Vice-Chair Daniel J. Anzia, M.D. Ian A. Cook, M.D. Molly T. Finnerty, M.D. Bradley R. Johnson, M.D. James E. Nininger, M.D. Paul Summergrad, M.D. Sherwyn M. Woods, M.D., Ph.D. Joel Yager, M.D. AREA AND COMPONENT LIAISONS Robert Pyles, M.D. (Area I) C. Deborah Cross, M.D. (Area II) Roger Peele, M.D. (Area III) Daniel J. Anzia, M.D. (Area IV) John P. D. Shemo, M.D. (Area V) Lawrence Lurie, M.D. (Area VI) R. Dale Walker, M.D. (Area VII) Mary Ann Barnovitz, M.D. Sheila Hafter Gray, M.D. Sunil Saxena, M.D. Tina Tonnu, M.D. STAFF Robert Kunkle, M.A., Senior Program Manager Amy B. Albert, B.A., Assistant Project Manager Laura J. -

CLAUDIA HART B

CLAUDIA HART b. 1955, New York, NY Lives and works in New York, NY Claudia Hart emerged as part of a generation of ‘90s intermedia artists examining issues of identity and representation. Since the late ‘90s when she began working with 3D animation, Hart embraced these same concepts, but now focusing on the impact of computing and simulation technologies. She was an early adopter of virtual imaging, using 3D animation to make media installations and projections, and later as they were invented, other forms of VR, AR and objects produced by computer-driven production machines. At the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, where she is a professor, she developed a pedagogic program based on her practice - Experimental 3D - the first dedicated solely to teaching simulations technologies in an art-school context. Hart’s works are widely exhibited and collected by galleries and museums including the collections of the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Museum of Modern Art, and the Metropolitan Museum. Her work has been shown at the New Museum, produced at the Eyebeam Center for Art + Technology, where she was an honorary fellow in 2013-14, at Pioneer Works, NY, where she a technology resident in 2018, and at the Center for New Music and Audio Technology, UC California, Berkeley where she is currently a Fellow. She is represented by bitforms gallery. bitforms gallery | 131 Allen Street New York, NY 10002 | t 212 366 6939 | www.bitforms.art EDUCATION 2001 New York University, Center for Advanced Digital Applications, Certificate in Computer Animation 1984 Columbia University Graduate School of Architecture, M.S. -

Claudia Hart Welcome to Alice's Gift Shop!

For Immediate Release bitforms gallery nyc Contact: Laura Blereau 529 West 20th St [email protected] New York NY 10011 www.bitforms.com (212) 366-6939 Claudia Hart Welcome to Alice’s Gift Shop! May 3 – May 31, 2014 bitforms gallery nyc Reception: Sat, May 3, 6:00 – 8:30 PM Gallery Hours: Tue – Sat, 11:00 AM – 6:00 PM bitforms gallery is pleased to announce Welcome to Alice’s Gift Shop!, a third solo exhibition with Claudia Hart. Featuring the New York debut of Hart’s augmented reality tableware and quilts, the exhibition includes three new participatory projects that engage virtual worlds, literary nonsense and domestic craftsmanship. The works are inspired by Lewis Carroll’s 1865 Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and explore a populist culture so addicted to the devices of high technology that it can only bear a world that is filtered through them. Using a variety of platforms, Hart’s new work present two realities: the physical and the hidden; or the dormant and the expressive. Steeped in the clichés of data-driven, punk and Romantic aesthetics, the works build a space that is interactive and irrational. Each composition is navigable using hand-held devices, which deliver animated and text-based content. Programmed by the artist, these multimedia objects craft metaphors that unfold using computer-vision, revealing “magical” layers of new information. The spectacle of new technology complicates three-dimensional form, as Hart pairs technical precision with raw, emotional subjectivity. Over the past fifteen years, Hart’s practice has increasingly focused on notions of the digital body. -

Virtually Real. Conversations on Technobody - Part I

Search GO Editorial Artist Index Apply as Gallery Newswire About or Organization Art Calendar Contact Editions Exhibition / Virtually Real. Conversations On TechNoBody - Part I In the Digital Art Series On January 23, 2015, TechNoBody opened at Pelham Art Center in New York, a group exhibition exploring “the mediated world’s impact on and relationship to the physical body in an increasingly virtual world.” Presenting works by seven artists working with a variety of media, TechNoBody investigates the perceptions and experiences of the body but also the immixture of technological and scienti몭c concepts in the TechNoBody language of art. From Claudia Hart’s critique of digital technology and the misogyny of gaming and special effects media to Carla Gannis’s Open performance video where the artist competes with her virtual self; from January 23 – March 21, 2015 Cynthia Lin’s monumental drawings detailing minuscule portions of skin to at Pelham Art Center Laura Splan’s mixture of scienti몭c and domestic in molecular garments and Joyce Yu-Jean Lee’s challenge of conventional viewing perspectives; from Pelham Art Center’s mission is to Christopher Baker’s examination on participative media to Victoria Vesna’s provide the public with a place, collaborative project on social networking, identity ownership and the idea the resources and the opportunity of a “virtual body” – the show guides the viewer through an array of to see, study, and experience the captivating approaches that challenge not only current media ideologies but arts in a community setting. also conceptual paradigms underlying today’s digital art, the question of Currently serving more than 16,000 adults and children in disembodiment and post-humanism in particular. -

Claudia Hart When a Rose Is Not a Rose Oct 25

For Immediate Release bitforms gallery nyc Contact: Natalia Pudzisz 529 West 20th St [email protected] New York NY 10011 www.bitforms.com (212) 366-6939 Claudia Hart When A Rose is Not a Rose Oct 25 – Dec 3, 2011 bitforms gallery nyc Reception: Saturday, Oct 29, 6:00 – 8:30 PM Gallery Hours: Tue – Sat, 11:00 AM – 6:00 PM bitforms gallery is pleased to announce a second solo exhibition with the Chicago-based artist Claudia Hart. When A Rose is Not a Rose, Hart’s reflection on the ubiquitous Gertrude Stein poem from 1913, presents the artist’s recent explorations on her own denial of death. The exhibition’s muted wall text, “When this you see remember me”, also quotes the title of W.G. Roger’s biography on Stein, functioning as a cold reminder of mortality, a memento mori. Primarily using photography and animated video, Hart crafts compelling metaphors for Freud’s das unheimlich (the uncanny) in virtual statues and models that are filled with human emotion, such as loss, pain and the fear of death. Psychically charged, these pieces present the viewer with objects that are simultaneously dead and alive - uncanny in the sense that they are realistic, but impossibly so. In addition to working with the human figure, Hart’s recent musings on the death of food also feature in this debut of The Real and The Fake, a new series of photographs. “The impulse to use technology as a means to control nature is inherently Modernist,” says Hart. “There is a built in uncanniness in the tools, which create meta-planes that fix a user’s body into a virtual space that is beyond time and death.” Using 3-D digital media as a means to consider our culture’s detachment from human vulnerability, Hart plays with the grotesque edge of the uncanny valley. -

Download the Press Release

D i M o D A a virtual institution from Alfredo Salazar-Caro and William Robertson November 14 – December 19, 2015 Virtual installation view, DiMoDa Main Pavilion, Alfredo Salazar-Caro and William Robertson TRANSFER is pleased to present the first installation of ‘DiMoDA’, The Digital Museum of Digital Art in conjunction with The Wrong New Media Biennale. DiMoDA is a preeminent virtual institution and a virtual reality exhibition platform dedicated to the distribution and promotion of New Media Art. For it's debut, DiMoDA will be presenting works by Claudia Hart (NY/CHICAGO), Tim Berresheim (DE) Jacolby Satterwhite (NY) and a project by Aquanet 2001 (Salvador Loza and Gibran Morgado) from Mexico City. Conceived in 2013 by Alfredo Salazar-Caro and William James Richard Robertson, DiMoDA launches in November of 2015 with its first exhibition as a pavilion in The Wrong Biennale and a physical exhibition at TRANSFER in New York from November 14 through December 19th, 2015. The atrium of the museum is architected and modeled in 3D by Alfredo Salazar-Caro. Viewers wearing the Oculus Rift to enter DiMoDA will approach a number of ‘portals’ which can be used to access the ‘wings’ of the museum. Exhibiting artists have complete control to shape the virtual environment in which their works are installed inside the museum. As a virtual institution, DiMoDA is dedicated to collecting, preserving, interpreting and exhibiting Digital artworks from living New Media artists, while expanding the conscious experience of viewing Digital art in a Virtual space. The DiMoDA building is intended as a home for contemporary digital art and incubator for new ideas, as well as an architectural contribution to the Internet’s virtual landscape. -

Cv. Mary Ellen Strom.5-13

MARY ELLEN STROM ARTIST – EDUCATOR – CURATOR [email protected], 347-573-7782 (mobile) MARYELLENSTROM.COM SOLO EXHIBITIONS AND COLLABORATIVE PROJECTS 2020 Stand by Snow: Chronicles of a Heat Wave, opera for opening of Story Mill Park, Bozeman, MT 2019 FLOW, Mountain Time Arts, public artwork 2018 Cherry River, public artwork, Missouri Headwaters State Park, Gallatin County, MT, collaboration with Dr. Shane Doyle 2018 Picture Bayview, Site Specific Installation at Bayview Opera House, Bayview-Hunters Point, SF, CA collaboration with choreographer, Joanna Haigood and composer, Walter Kintindu 2017 Gabriel Canal, public artwork, Kelly Ranch, Bozeman, MT 2016 Grey Eagle, solo gallery exhibition, 555 Gallery, Boston, MA 2016 FLOW, public artwork, Story Mill Grain Terminal, Bozeman, MT 2014 Snow, solo gallery exhibition, Longhouse Projects, NY, NY 2010 Meadowlark, solo gallery exhibition, Alexander Grey, NY, NY 2009 New Performance Video Exhibition, Mary Ellen Strom and Ann Carlson, DeCordova Museum, Lincoln, MA January 24, 2009 – May 17, 2009, curator, Dina Deitsch 2008 Madame 710, solo gallery exhibition, Judi Rotenberg Gallery, Boston, MA 2008 Simulating Buffalo, site-specific installation, M. Strom and A. Carlson, Myrna Loy Center, Helena, MT 2007 Work, solo gallery exhibition, Alexander Grey, NY, NY 2007 Work, solo gallery exhibition, St. Gauden’s Fellowship, St. Gauden’s Gallery, Cornish, NH 2006 Recognition, solo gallery exhibition, Judi Rotenberg Gallery, Boston, MA 2005 The Nudes, solo gallery exhibition, Judi Rotenberg -

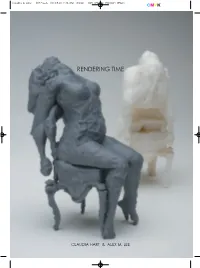

Rendering Time

Claudia & Alex - 갤러리도스 2013.5.10 2:36 PM 페이지1 005 175Line 2540DPI 175LPI RENDERING TIME CLAUDIA HART & ALEX M. LEE Claudia & Alex - 갤러리도스 2013.5.10 2:36 PM 페이지2 005 175Line 2540DPI 175LPI Rendering Time Claudia Hart & Alex M. Lee 2013. 5. 15. Wed ˗5. 21. Tue cover image ▷ Claudia Hart Motification 01 2007-08 ◁ Alex M Lee untitled (Rugen) 2013 115-52, Palpandong, Jongrogu, Seoul, Korea / Tel. 82 2 737 4678 / www.gallerydos.com Claudia & Alex - 갤러리도스 2013.5.10 2:36 PM 페이지3 005 175Line 2540DPI 175LPI Nicholas O’Brien Within the work of Claudia Hart and Alex Lee,a strand of romantic sensitivity and powerful quietude weaves its way through a visually distinct digital fabric. The computer-rendered garment of their work contains both a serene stillness and the lush vibrancy of a delicate, warm, embracing cloth. Hart and Lee don this airy robe not to signify some position of authority, but instead to be enveloped by thedeliberate and humble intention of renewing the visual and metaphorical underpinnings of Romanticism. For these two artists, this reinvestigation stems from the myriad of political, spatial, and aesthetic concerns that new technologiespose to traditional notions of the sublime, the body and the virtual, found within Romantic thinking. The particular technologies that are most wrought with these questions are those that both artists employ: 3D animation, rapid-prototype printing,mobile application, digital photography, and networked technology. In doing so, Hart and Lee expose the ways in which Romantic thought and vision have influenced new media production by striking new territory into a profoundly self-reflexive terrain.