Issue 3 Autumn 2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Inspecting the Works! JOURNAL

Quarterly Magazine February 2021 No 163 JOURNAL Price £2.50 Inspecting the works! The Friends of the Settle - Carlisle Line FRIENDS OF THE SETTLE – CARLISLE LINE Settle Railway Station, Station Road, Settle, North Yorkshire BD24 9AA President: The Right Hon. Michael Portillo. Vice Presidents: Lord Inglewood DL; The Bishop of Carlisle; Edward Album; Olive Clarke, OBE, JP, DL; Ann Cryer; David Curry; Douglas Hodgins; Philip Johnston; Eric Martlew; Richard Morris; Mark Rand; Pete Shaw; Ken Shingleton; Brian Sutcliffe MBE; David Ward. Chairman: Paul Brown - [email protected] Committee: Edward Album (Legal Officer) [email protected] John Carey (Walks Co-ordinator & Integrated Transport Representative) [email protected] Allison Cosgrove (Vice Chair) allison.cosgrove@ settle-carlisle.com Joanne Crompton (Assistant Treasurer) [email protected] * John Ingham (Treasurer) [email protected] Paul Kampen (Secretary & Editor) [email protected] Ruth Evans (Volunteers Co-ordinator & Events Organiser) [email protected] Roger Hardingham (Trading Manager) [email protected] Paul Levet (Train Service Development) [email protected] Rod Metcalfe (On-train Guide Co-ordinator & Technology Adviser) [email protected] Richard Morris (Webmaster) [email protected] * Pete Myers [email protected] Martin Pearson [email protected] Pat Rand (Customer Relations Manager) [email protected] * * Indicates member co-opted after the 2020 AGM in accordance with the FoSCL constitution. Postal Addresses: Secretarial Enquiries, Hard Copy for the Magazine and General Postal Enquiries: Paul Kampen - 74 Springfield Road, Baildon, Shipley, W. Yorks BD17 5LX. Facebook @FriendsSettleCarlisle Twitter @foscl Enquiries about Volunteering: Ruth Evans - 49 Kings Mill Lane, Settle BD24 9FD or email as above. -

YORKSHIRE DALES SOCIETY EVENTS CATEGORIES in SEARCH of the an Enjoyable Mix of Events Designed with Something for Everyone

Autumn 2016 : Issue 136 ING & ENJO CT YI TE NG RO F P O , R G T IN H I IN R T A Y P F M I V A E C Y • E A R A S • N N Y I V R E R S A CAMPAIGN • PROTECT • ENJOY • AN EXPANDED NATIONAL PARK – A HISTORIC DAY AND FANTASTIC OPPORTUNITY • • WALKING THE LIMESTONE PAVEMENTS OVER ORTON FELLS • • NATIONAL TRUST: WORKING TOWARDS MORE NATURAL LANDSCAPES IN THE DALES • • THE WENSLEYDALE PROJECT: YORE PAST, URE FUTURE • • WHAT BREXIT MEANS FOR THE YORKSHIRE DALES • Cover photo: Intrepid YDS Members cross the stream at Nethergill Farm, photo Tim Hancock This page: Aysgarth Falls, photo David Higgins, The Wensleydale Project, Yore Past, Ure Future, page 8 CONTENTS Autumn 2016 : Issue 136 AN EXPANDED NATIONAL PARK: Page 3 OS MAPS A VERY USEFUL APP Page 13 A HISTORIC DAY AND A FANTASTIC OPPORTUNITY HELP US TO KEEP THE WALKING THE YORKSHIRE DALES VIBRANT: Page 14 LIMESTONE PAVEMENTS THROUGH A LEGACY GIFT OVER ORTON FELLS Page 4-5 NEW YDS NATIONAL TRUST: Page 6-7 BUSINESS MEMBERS Page 14-15 WORKING TOWARDS MORE NATURAL HYPERCAST IN THE DALES Page 15 LANDSCAPES IN THE DALES CHRISTMAS GIFT OFFER Page 15 THE WENSLEYDALE PROJECT: Page 8 YORE PAST, URE FUTURE AN ACT OF FAITH Page 16 CAPTURING THE PAST: Page 9 BOOK REVIEW Page 17 OFF TO A GOOD START PRIMULA FARINOSA: Page 17 35TH ANNIVERSARY THE BIRD'S EYE PRIMROSE AND HIGHLIGHT: Page 10-11 OUR SOCIETY LOGO A VISIT TO NETHERGILL ECO FARM YORKSHIRE DALES SOCIETY'S EVENTS Page 18-19 WHAT BREXIT MEANS FOR THE YORKSHIRE DALES Page 12-13 Editor Fleur Speakman 2 Email: [email protected] AN EXPANDED NATIONAL PARK A HISTORIC DAY AND A FANTASTIC OPPORTUNITY armly greeted by a great crowd of well-wishers, the favour. -

The Friends of the Settle

Quarterly Magazine February 2013 No 131 JOURNAL Price £2.50 Destination Settle-Carlisle? The Friends of the Settle - Carlisle Line FRIENDS OF THE SETTLE – CARLISLE LINE Settle Railway Station, Station Road, Settle, North Yorkshire BD24 9AA President: The Hon. Sir William McAlpine Bt. Vice Presidents: Lord Inglewood DL; The Bishop of Carlisle; Edward Album; Ron Cotton; Ann Cryer ; David Curry; Philip Johnston; Eric Martlew; Pete Shaw; Ken Shingleton; Brian Sutcliffe MBE; Gary Waller; David Ward. Chairman: Richard Morris - richard.morris @settle-carlisle.com Committee: Douglas Hodgins (Vice-chairman & Stations Co-ordinator) [email protected] Mark Rand (Immediate Past Chairman and Media Relations Officer) [email protected] Stephen Way (Treasurer) [email protected] Paul Kampen (Secretary & Editor) [email protected] Peter Davies (Membership Secretary) [email protected] Ruth Evans (Volunteers Co-ordinator and Events Organiser) [email protected] Alan Glover (On-train Guides Co-ordinator) [email protected] John Johnson (Armathwaite signalbox & Carlisle representative) [email protected] Paul Levet* (Business Development Co-ordinator) [email protected] Rod Metcalfe * (On-train Guide Planner and Technology Adviser) [email protected] Pat Rand (Customer Relations, Trading and Settle Shop Manager) [email protected] Pete Shaw (Heritage & Conservation Officer) Telephone 01274 590453 Craig Tomlinson* (Stations Representative) [email protected] Nigel Ward (Hon. Solicitor) [email protected] * Indicates that these members were co-opted after the 2012 Annual General Meeting in accordance with the FoSCL constitution. Postal Addresses: Chairman: Richard Morris – 10 Mill Brow, Armathwaite, Carlisle CA4 9PJ Secretarial Enquiries, Hard Copy for the Magazine and General Postal Enquiries: Paul Kampen - 74 Springfield Road, Baildon, Shipley, W. -

Directory of Resources

SETTLE – CARLISLE RAILWAY DIRECTORY OF RESOURCES A listing of printed, audio-visual and other resources including museums, public exhibitions and heritage sites * * * Compiled by Nigel Mussett 2016 Petteril Bridge Junction CARLISLE SCOTBY River Eden CUMWHINTON COTEHILL Cotehill viaduct Dry Beck viaduct ARMATHWAITE Armathwaite viaduct Armathwaite tunnel Baron Wood tunnels 1 (south) & 2 (north) LAZONBY & KIRKOSWALD Lazonby tunnel Eden Lacy viaduct LITTLE SALKELD Little Salkeld viaduct + Cross Fell 2930 ft LANGWATHBY Waste Bank Culgaith tunnel CULGAITH Crowdundle viaduct NEWBIGGIN LONG MARTON Long Marton viaduct APPLEBY Ormside viaduct ORMSIDE Helm tunnel Griseburn viaduct Crosby Garrett viaduct CROSBY GARRETT Crosby Garrett tunnel Smardale viaduct KIRKBY STEPHEN Birkett tunnel Wild Boar Fell 2323 ft + Ais Gill viaduct Shotlock Hill tunnel Lunds viaduct Moorcock tunnel Dandry Mire viaduct Mossdale Head tunnel GARSDALE Appersett Gill viaduct Mossdale Gill viaduct HAWES Rise Hill tunnel DENT Arten Gill viaduct Blea Moor tunnel Dent Head viaduct Whernside 2415 ft + Ribblehead viaduct RIBBLEHEAD + Penyghent 2277 ft Ingleborough 2372 ft + HORTON IN RIBBLESDALE Little viaduct Ribble Bridge Sheriff Brow viaduct Taitlands tunnel Settle viaduct Marshfield viaduct SETTLE Settle Junction River Ribble © NJM 2016 Route map of the Settle—Carlisle Railway and the Hawes Branch GRADIENT PROFILE Gargrave to Carlisle After The Cumbrian Railways Association ’The Midland’s Settle & Carlisle Distance Diagrams’ 1992. CONTENTS Route map of the Settle-Carlisle Railway Gradient profile Introduction A. Primary Sources B. Books, pamphlets and leaflets C. Periodicals and articles D. Research Studies E. Maps F. Pictorial images: photographs, postcards, greetings cards, paintings and posters G. Audio-recordings: records, tapes and CDs H. Audio-visual recordings: films, videos and DVDs I. -

Tornado Railtours

Tornado Railtours 2021 Terms and Conditions are available on request and can be read at any time at a1steam.com/railtours If you no longer wish to receive tour brochures, please email [email protected] Front cover photo: Peter Backhouse 2 Welcome 2020 has been a challenge to all of us, and if ever there was a time to have something to look forward to it is now. After a difficult year when many have experienced the disappointment of cancelled plans, we are proud to bring you our programme for 2021. We hope that you can join us on one of our tours and enjoy a great experience with Tornado. Liam Barnes Our first tours of the year fall on Valentine’s Due to popular demand, there are a number of weekend when Tornado will haul two circular trains trains which cross the Settle and Carlisle Railway. around Yorkshire and the North East. The perfect Its rolling landscape scattered with epic tunnels excuse for some steamy romance, these trains and soaring viaducts presents any locomotive a offer shorter days and are competitively priced. The challenging journey, and passengers continue to be evening train will see Tornado visit Harrogate and thrilled by the sound of Tornado hard at work on this Knaresborough for the first time. stunningly beautiful stretch of railway. There are more “firsts” for Tornado in 2021, including Heading into autumn, we are pleased to offer four our first tours from Hull and the East Riding, trains across the S&C with both Tornado and Flying Liverpool and Glasgow. -

Cpaddress TRADEAS a & G Catering, Boston Hotel Blenheim

CPAddress TRADEAS A & G Catering, Boston Hotel Blenheim Terrace, Scarborough, North Yorkshire, YO12 7HF A & G Catering A J's (mcgill & Son), 8 Marine Parade, Whitby, North Yorkshire, YO21 3PR A J's (mcgill & Son) A L Dickinson & Son, Sawdon Heights, Sawdon, Scarborough, North Yorkshire, YO13 9EB A L Dickinson & Son A P Jackson, 10 High Street, Ruswarp, Whitby, North Yorkshire, YO21 1NH A P Jackson A Taste Of Magic, 14 Victoria Road, Central, Scarborough, North Yorkshire, YO11 1SD A Taste Of Magic Aartswood, 27 Trafalgar Square, Northstead, Scarborough, North Yorkshire, YO12 7PZ Aartswood Abacus Hotel, 88 Columbus Ravine, Central, Scarborough, North Yorkshire, YO12 7QU Abacus Hotel Abbey House Tea Room, Youth Hostel, Abbey House, East Cliff, Whitby, North Yorkshire, YO22 4JT Abbey House Tea Room Abbey Steps Tea Rooms, 117 Church Street, Whitby, North Yorkshire, YO22 4DE Abbey Steps Tea Rooms 8A West Square, Scarborough, North Yorkshire, YO11 1TW Abbeydale Guest House Abbots Leigh, 7 Rutland Street, Filey, North Yorkshire, YO14 9JA Abbots Leigh 5 Argyle Road, Whitby, North Yorkshire, YO21 3HS Abbotsleigh Acacia Guest House, 125 Columbus Ravine, Central, Scarborough, North Yorkshire, YO12 7QZ Acacia Guest House Ackworth House, The Beach, Filey, North Yorkshire, YO14 9LA Ackworth House Hillcrest, Suffield Hill, Suffield, Scarborough, NORTH YORKSHIRE, YO13 0BJ Adam Adene Private Hotel, 39 Esplanade Road, Weaponness, Scarborough, North Yorkshire, YO11 2AT Adene Private Hotel Admiral Hotel, 13 West Square, Castle, Scarborough, North Yorkshire, -

What's on in the Yorkshire Dales in 2018

WHAT’S ON IN THE YORKSHIRE DALES IN 2018 Whether you want to visit a traditional Dress appropriately for walks and outdoor Dales agricultural show, become a nature activities - the weather in the Dales can be Dogs detective or challenge yourself to learn a changeable. Bring drinks and snacks, wear Dogs are welcome at many events, but new skill, there is something for you. suitably stout footwear, and carry clothing please assume they are NOT permitted to suit all conditions. The fantastic events listed here are hosted and always contact the organiser by a wide variety of organisations. Use the Visit www.yorkshiredales.org.uk/events beforehand to avoid disappointment. contact details provided to find out more for further details on these and many Where dogs are allowed they must be on the one you are interested in - booking more events across the Yorkshire Dales fit enough to negotiate stiles and is essential for some. throughout 2018. steep ascents, be well-behaved, and Disclaimer be kept under close control on a The Yorkshire Dales National Park Authority cannot You are STRONGLY ADVISED to contact the event short fixed lead at all be held responsible for any omissions, subsequent provider to confirm the information given BEFORE times. Assistance dogs changes or revisions that may occur with events setting out. All information included is believed to be information supplied by external agencies. correct at the time of going to print. are always welcome. Events shown with a blue background are Give your Booking organised by the Yorkshire Dales National Park Authority. We are holding over 140 car a break Some of our most popular events in 2018, all led by our knowledgeable must be pre-booked and pre-paid to Many National Park events can be Dales Volunteers, specialist staff or invited guarantee a place. -

Challenge Notes

UK Yorkshire Three Peaks Weekend Duration: 3 days This region was shaped by glaciers many thousands of years ago, and there are plenty of geological landmarks – striking limestone outcrops and unusual rock formations – to pique our interest as we walk. We will also see the famous Ribblehead Viaduct enroute, part of the scenic Settle to Carlisle railway line. This is an extremely tough event over hilly landscapes; at 24 miles it forms an enormous challenge for walkers. DETAILED ITINERARY Day 1: Arrive Camp, Yorkshire Dales We meet late afternoon at our campsite near Chapel-le-Dale, nestled between two of our three peaks. After dinner and a thorough trip briefing we prepare our kit and get a good night’s sleep, ready for tomorrow’s strenuous challenge! Day 2: Ingleborough & Whernside After a good fuelling breakfast in camp, we set off, walking south through the broad green dale, criss-crossed with dry-stone walls. Ingleborough’s stepped shape - due to its alternating layers of limestone, sandstone and shale – rises before us. Whernside, our second peak, dominates the landscapes behind us. We pass through the village of Chapel-le-Dale and soon reach the base of Ingleborough (723m), where a stepped path zig-zags fairly steadily to the summit of our first peak. We soak up the views over the surrounding dramatic landscapes, an area of rocky outcrops and limestone scars, and the impressive sight of the famous 400m-long Ribblehead Viaduct, built in the 1870s. We then descend along a ridge to the valley below, where we walk parallel to the Settle – Carlisle Railway, enjoying WWW.DISCOVERADVENTURE.COM || 01722 718444 AITO Assured PAGE 2 a flattish section! We pass through Ribblehead, at the head of Chapel-le-Dale, and can admire the Viaduct from close quarters. -

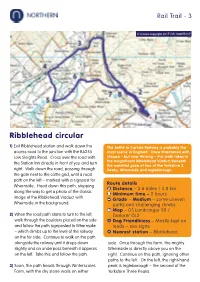

Ribblehead Circular

Rail Trail - 3 © Crown copyright 2017 OS 100055187 Ribblehead circular 1) Exit Ribblehead station and walk down the The Settle to Carlisle Railway is probably the access road to the junction with the B6255 most scenic in England. Once threatened with Low Sleights Road. Cross over the road with closure – but now thriving – this walk takes in the Station Inn directly in front of you and turn the magnificent Ribblehead Viaduct beneath the watchful gaze of two of the Yorkshire 3 right. Walk down the road, passing through Peaks, Whernside and Ingleborough the gate next to the cattle grid, until a road path on the left – marked with a signpost for Route details Whernside. Head down this path, stopping Distance – 3.6 miles / 5.8 km along the way to get a photo of the classic Minimum time – 2 hours image of the Ribblehead Viaduct with Grade – Medium – some uneven Whernside in the background. paths and challenging climbs Map – OS Landranger 98 / 2) When the road path starts to turn to the left, Explorer OL2 walk through the boulders placed on the side ICONSDog Friendliness –7.3 Mostly kept on and follow the path signposted to Whernside Transportleads – see signs – which climbs up to the level of the railway Nearest station – Ribblehead Train Underground Light Railway Car Taxi Bus / Coach Bicycle on the far side. Continue to walk on the path Tram Motor Bike Airport Seaport National Rail Transport for First Class alongside the railway until it drops down side. Once throughLondon the farm, the mighty slightly and an underpass beneath it appears Whernside is directly above you on the on the left. -

April 2017 KENDAL UNITARIAN CHAPEL Nurturing Faith

KENDAL UNITARIAN CHAPEL Nurturing faith. Embracing life. Celebrating difference. April 2017 KENDAL UNITARIAN CHAPEL Nurturing faith. Embracing life. Celebrating difference. charity number 236829 HUwww.ukunitarians.org.uk/kendal U WELCOME to Kendal Unitarians Unitarians are very different We don't have a particular set of beliefs that we expect you to agree with. Everyone who comes to the chapel is free to discover their own spiritual path. We welcome people on any point of their spiritual journey: those who have been seeking elsewhere or those whose journey has only just begun. We believe everyone has the right to seek truth and meaning for themselves in mutual respect, and that reason and conscience are our best guides. Our congregation includes people who are Christian, humanists, pagans, agnostics, etc., or a mixture of all of these! Cover photo: Beck Head © Mike Oram 2013 1 2 Fairtrade Update Our Service on 5 March, as part of Fairtrade Fortnight, turned into what I described as Brexit, Bananas and Bees. It was good to have Janet and Delphine from the Kendal Fairtrade Group with us. Janet outlined some of the issues that will be important to consider as the UK negotiates new trade deals, and Delphine made mention of a film she had seen the previous day about the illegal trafficking of children for use in the cocoa production in- dustry. On the following Wednesday, I was able to attend the Roman Catholic Church of Holy Trinity and St George in Kendal to hear a pres- entation by Charles Chavi who is a Fairtrade sugar producer in Malawi. -

Free Please Take One

Free PLeASe TAKe ONe THe MAGAZINe OF WeST BerKSHIre CAMrA AUTUMN 2018 Outstanding Community Pub awards Over 100 nominations were received for the 2018 West Berkshire Community Pub of the Year award. To recognise their important role in different environments, the award is shared between the Cottage Inn , Upper Bucklebury, the Old London Apprentice and the Cow & Cask , Newbury. Saturday This is the fifth time that the Cottage Inn has 8th September 2018 been recognised and reflects huge support from NORTHCROFT FIELDS customers for Gary Bush and his team. 12 noon ONWARDS One nomination stated ‘Gary has made the #n outside very family friendly – on the big field, • LIVE MUSIC raf18 perfect for kids to run around in, there is a new • DELICIOUS FOOD Y climbing frame and other play equipment, and • OVER 100 BEERS & CIDERS BU OU R a fenced area with goats, chickens and rabbits • A GREAT LOCAL DAY OUT Y ETS TICK E which the children love’. Burns Night, bonfire LIN ON k token tra drin night, Tour de Berkshire charity cycle ride and FREE ex online h every wit rchased classic car rallies at the ‘genuinely cherished icket pu t C’s t to T & community asset’ featured in many Subjec The Cottage Inn - Gary Bush nominations. www.newburyrealale.co.uk /NewburyRealAleFestival /NewburyAleFest /NewburyAleFest Previous winners, The Tally Ho , Hungerford community pub’. The What’s On blackboard at the front of the pub displays the wide range of Newtown and the Three Horseshoes , Brimpton Visit the West Berkshire CAMRA stand at were the other country pubs with strong cases. -

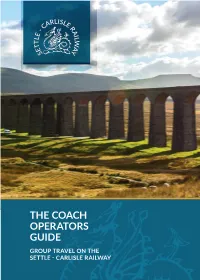

The Coach Operators Guide

THE COACH OPERATORS GUIDE GROUP TRAVEL ON THE SETTLE - CARLISLE RAILWAY WELCOME TO THE SETTLE & CARLISLE RAILWAY Explore one of the world’s greatest railway journeys... This world-famous railway line carves its way through some of the Yorkshire Dales’ most dramatic scenery and the remote fells of Westmorland. The hard climbing done; it then passes through Cumbria’s verdant Eden Valley before arriving at the historic border city of Carlisle. The Settle to Carlisle railway has become etched in history as the line they tried to close– but failed. More than 25 years ago, it came perilously close to being shut forever but, at the last moment, was reprieved. Since then, it has gone from strength to strength and is loved for its sense of history and the impossibly dramatic setting. From Leeds, the line passes through West Yorkshire to Skipton where the Yorkshire Dales begin. Settle is the gateway to the spectacular Three Peaks area (Pen-y-Ghent, Ingleborough and Whernside), in the heart of which sits the Ribblehead viaduct. A testament to Victorian engineering and the tenacity of the men who built it, the structure needs to be viewed in its position to be believed. The climb continues to the line’s highest point at Ais Gill, giving an awe-inspiring vista of Dentdale along the way. The craggy sides of Mallerstang signal the start of the descent into Cumbria’s Eden Valley. Isolated farms and waterfalls pepper the valley sides, and, by Kirkby Stephen, the landscape has become increasingly lush and verdant. At Appleby, red sandstone buildings surround a medieval castle in this pretty market town with beautiful riverside walks.