The National Flood Insurance Program at Fifty: How the Fifth Amendment Takings Doctrine Skews Federal Flood Policy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

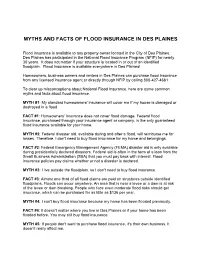

Myths and Facts of Flood Insurance in Des Plaines

MYTHS AND FACTS OF FLOOD INSURANCE IN DES PLAINES Flood insurance is available to any property owner located in the City of Des Plaines. Des Plaines has participated in the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) for nearly 30 years. It does not matter if your structure is located in or out of an identified floodplain. Flood Insurance is available everywhere in Des Plaines! Homeowners, business owners and renters in Des Plaines can purchase flood insurance from any licensed insurance agent or directly through NFIP by calling 800-427-4661. To clear up misconceptions about National Flood Insurance, here are some common myths and facts about flood insurance. MYTH #1: My standard homeowners' insurance will cover me if my house is damaged or destroyed in a flood. FACT #1: Homeowners' insurance does not cover flood damage. Federal flood insurance, purchased through your insurance agent or company, is the only guaranteed flood insurance available for your home. MYTH #2: Federal disaster aid, available during and after a flood, will reimburse me for losses. Therefore, I don't need to buy flood insurance for my home and belongings. FACT #2: Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) disaster aid is only available during presidentially declared disasters. Federal aid is often in the form of a loan from the Small Business Administration (SBA) that you must pay back with interest. Flood insurance policies pay claims whether or not a disaster is declared. MYTH #3: I live outside the floodplain, so I don't need to buy flood insurance. FACT #3: Almost one third of all flood claims are paid on structures outside identified floodplains. -

The Effects of Flood Insurance on Housing Markets

The Effects of Flood Insurance on Housing Markets by Agustín Indaco, Francesc Ortega, and Süleyman Tas¸pınar Agustín Indaco Carnegie Mellon University in Qatar Francesc Ortega Süleyman Tas¸pınar Queens College, City University of New York Abstract In this article, we analyze the role of flood insurance on the housing markets of coastal areas. To do so, we assembled a parcel-level dataset of the universe of residential sales for two coastal urban areas in the United States—Miami-Dade County (2008–15) and Virginia Beach (2000–16)—matched with their Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) flood maps, which characterize the flood-risk level for each property. First, we compare trends in housing values and sales activity among properties on the floodplain, as defined by the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP), relative to properties located elsewhere within the same area. Despite the heightened flood risk in the past two decades, we do not find evidence of divergent trends. Second, we analyze the effects of the recent reforms to the NFIP. In 2012 and 2014, Congress passed legislation announcing important increases in insurance premiums and flood map updates. We find robust evidence of large price reductions for properties that were drawn into the flood zone of the new FEMA flood maps. We estimate that, as a result of the mandatory insurance requirement in the flood zone, NFIP insurance costs for such properties in Virginia Beach will increase by an average of about $3,500 per year and lead to a reduction in housing values of about $64,000. Cityscape: A Journal of Policy Development and Research • Volume 21, Number 2 • 2019 Cityscape 129 U.S. -

A Homeowners Guide to Understanding Flood Insurance

A Homeowners Guide to Understanding Flood Insurance 1. What causes floods? Many conditions can result in a flood: hurricanes, over-topped levees, clogged drainage systems, rapid accumulation of rainfall, snowmelt, and more. Streams, rivers, lakes, and oceans can all cause flooding. 2. How can I obtain flood insurance? Flood insurance is available from the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) and is sold through insurance agents like Gowrie Group. There is a 30-day waiting period in most cases. 3. When is flood insurance required? If a home is in a high risk flood zone (Zone A or V), lenders must, by law, require clients to buy flood insurance as a condition of the loan (mortgage). 4. Should I buy flood insurance even if I do not have a mortgage or my home is not in a high risk zone? In many cases, it is advisable to carry flood insurance regardless. The chance of a home suffering flood damage is many times more likely than being damaged by fire. One-quarter of all flood losses occur outside of the high risk flood zones. Homeowner’s insurance policies do NOT provide any coverage for losses related to floods. 5. What does the NFIP policy cover? NFIP flood insurance policies cover physical damage to homes and possessions. The maximum coverage for buildings is $250,000; the maximum for contents is $100,000. 6. What is NOT covered by a NFIP flood policy? There are many exclusions including property and belongings outside of the building - landscaping, wells, septic systems, walks, decks, patios, fences, seawalls, hot tubs, pools, currency, precious metals, valuable papers, basement contents, cars, and more. -

The National Flood Insurance Program: Selected Issues and Legislation in the 116Th Congress

The National Flood Insurance Program: Selected Issues and Legislation in the 116th Congress Updated December 23, 2019 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R46095 SUMMARY R46095 The National Flood Insurance Program: December 23, 2019 Selected Issues and Legislation in the 116th Diane P. Horn Congress Analyst in Flood Insurance and Emergency The National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) was established by the National Flood Management Insurance Act of 1968 (NFIA; 42 U.S.C. §4001 et seq.), and was most recently reauthorized until September 30, 2020 (P.L. 116-93). The general purpose of the NFIP is Baird Webel both to offer primary flood insurance to properties with significant flood risk, and to Specialist in Financial reduce flood risk through the adoption of floodplain management standards. A longer- Economics term objective of the NFIP is to reduce federal expenditure on disaster assistance after floods. The NFIP also engages in many “non-insurance” activities in the public interest: it disseminates flood risk information through flood maps, requires community land use and building code standards, and offers grants and incentive programs for household- and community-level investments in flood risk reduction. Unless reauthorized or amended by Congress, the following will occur on September 30, 2020: (1) the authority to provide new flood insurance contracts will expire and (2) the authority for NFIP to borrow funds from the Treasury will be reduced from $30.425 billion to $1 billion. Issues that Congress may consider in the context of reauthorization include (1) NFIP solvency and debt; (2) premium rates and surcharges; (3) affordability of flood insurance; (4) increasing participation in the NFIP; (5) the role of private insurance and barriers to private sector involvement; (6) non-insurance functions of the NFIP such as floodplain mapping and flood mitigation; and (7) future flood risks, including future catastrophic events. -

Arlington County, Virginia (All Jurisdictions)

VOLUME 1 OF 1 ARLINGTON COUNTY, VIRGINIA (ALL JURISDICTIONS) COMMUNITY NAME COMMUNITY NUMBER ARLINGTON COUNTY, 515520 UNINCORPORATED AREAS PRELIMINARY 9/18/2020 REVISED: TBD FLOOD INSURANCE STUDY NUMBER 51013CV000B Version Number 2.6.4.6 TABLE OF CONTENTS Volume 1 Page SECTION 1.0 – INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 The National Flood Insurance Program 1 1.2 Purpose of this Flood Insurance Study Report 2 1.3 Jurisdictions Included in the Flood Insurance Study Project 2 1.4 Considerations for using this Flood Insurance Study Report 2 SECTION 2.0 – FLOODPLAIN MANAGEMENT APPLICATIONS 13 2.1 Floodplain Boundaries 13 2.2 Floodways 17 2.3 Base Flood Elevations 18 2.4 Non-Encroachment Zones 19 2.5 Coastal Flood Hazard Areas 19 2.5.1 Water Elevations and the Effects of Waves 19 2.5.2 Floodplain Boundaries and BFEs for Coastal Areas 21 2.5.3 Coastal High Hazard Areas 21 2.5.4 Limit of Moderate Wave Action 22 SECTION 3.0 – INSURANCE APPLICATIONS 22 3.1 National Flood Insurance Program Insurance Zones 22 SECTION 4.0 – AREA STUDIED 22 4.1 Basin Description 22 4.2 Principal Flood Problems 23 4.3 Non-Levee Flood Protection Measures 24 4.4 Levees 24 SECTION 5.0 – ENGINEERING METHODS 27 5.1 Hydrologic Analyses 27 5.2 Hydraulic Analyses 32 5.3 Coastal Analyses 37 5.3.1 Total Stillwater Elevations 38 5.3.2 Waves 38 5.3.3 Coastal Erosion 38 5.3.4 Wave Hazard Analyses 38 5.4 Alluvial Fan Analyses 39 SECTION 6.0 – MAPPING METHODS 39 6.1 Vertical and Horizontal Control 39 6.2 Base Map 40 6.3 Floodplain and Floodway Delineation 41 6.4 Coastal Flood Hazard Mapping 51 6.5 FIRM -

National Flood Insurance Program: Selected Issues and Legislation in the 115Th Congress

National Flood Insurance Program: Selected Issues and Legislation in the 115th Congress Diane P. Horn Analyst in Flood Insurance and Emergency Management July 31, 2018 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov R45099 National Flood Insurance Program: Selected Issues and Legislation in the 115th Congress Summary The National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) was established by the National Flood Insurance Act of 1968 (NFIA, 42 U.S.C. §4001 et seq.), and was most recently reauthorized until November 30, 2018 (P.L. 115-225). The general purpose of the NFIP is both to offer primary flood insurance to properties with significant flood risk, and to reduce flood risk through the adoption of floodplain management standards. A longer-term objective of the NFIP is to reduce federal expenditure on disaster assistance after floods. The NFIP also engages in many “non-insurance” activities in the public interest: it disseminates flood risk information through flood maps, requires community land use and building code standards, and offers grants and incentive programs for household- and community-level investments in flood risk reduction. Unless reauthorized or amended by Congress, the following will occur on November 30, 2018: (1) the authority to provide new flood insurance contracts will expire and (2) the authority for NFIP to borrow funds from the Treasury will be reduced from $30.425 billion to $1 billion. The House passed H.R. 2874, the 21st Century Flood Reform Act, on November 14, 2017, on a vote of 237-189. H.R. 2874 would authorize the NFIP until September 30, 2022. Three bills have been introduced in the Senate to reauthorize the NFIP: S. -

Flood Disaster Protection Act, Interagency Examination Procedures

Interagency Consumer Laws and Regulations FDPA Flood Disaster Protection Act The National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) is administered primarily under the National Flood Insurance Act of 1968 (1968 Act) and the Flood Disaster Protection Act of 1973 (FDPA).1 The 1968 Act made federally subsidized flood insurance available to owners of improved real estate or mobile homes located in special flood hazard areas (SFHA) if their community participates in the NFIP. The NFIP, administered by a department of the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) known as the Federal Insurance and Mitigation Administration (FIMA), makes federally backed flood insurance available to consumers through NFIP Direct Program agents who deal directly with FEMA or through the Write Your Own Program (WYO), which allows consumers to purchase federal flood insurance from private insurance carriers. The NFIP aims to reduce the impact of flooding by providing affordable insurance to property owners and by encouraging communities to adopt and enforce floodplain management regulations. The FDPA requires federal financial regulatory agencies to adopt regulations prohibiting their regulated lending institutions from making, increasing, extending or renewing a loan secured by improved real estate or a mobile home located or to be located in an SFHA in a community participating in the NFIP unless the property securing the loan is covered by flood insurance. Flood insurance may be provided through the NFIP or through a private insurance carrier. Title V of the Riegle Community Development and Regulatory Improvement Act of 1994,2 which is called the National Flood Insurance Reform Act of 1994 (1994 Act), comprehensively revised the Federal flood insurance statutes. -

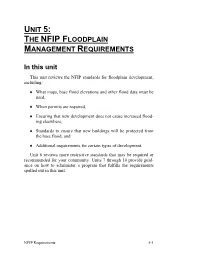

Unit 5: the Nfip Floodplain Management Requirements

UNIT 5: THE NFIP FLOODPLAIN MANAGEMENT REQUIREMENTS In this unit This unit reviews the NFIP standards for floodplain development, including: ♦ What maps, base flood elevations and other flood data must be used, ♦ When permits are required, ♦ Ensuring that new development does not cause increased flood- ing elsewhere, ♦ Standards to ensure that new buildings will be protected from the base flood, and ♦ Additional requirements for certain types of development. Unit 6 reviews more restrictive standards that may be required or recommended for your community. Units 7 through 10 provide guid- ance on how to administer a program that fulfills the requirements spelled out in this unit. NFIP Requirements 5-1 Contents A. The NFIP’s Regulations.................................................................................. 5-4 NFIP Regulations........................................................................................... 5-4 Community Types.......................................................................................... 5-6 B. Maps and Data................................................................................................. 5-8 NFIP Maps and Data...................................................................................... 5-8 When FIRM and Ground Data Disagree ....................................................... 5-9 Regulating Approximate A Zones ...................................................................10 Small developments.............................................................................. -

What Are the Different Flood Hazard Zone Designations Shown on a Flood Insurance Rate Map (FRIM), and What Do They Mean?

What are the different flood hazard zone designations shown on a Flood Insurance Rate Map (FRIM), and what do they mean? From FEMA website (10/17/2012): http://www.fema.gov/frequently-asked-questions- 1/insurance-professionals-lenders-frequently-asked-questions#in8 The zone designations shown on the FIRMs are defined below. Zone A Zone A is the flood insurance rate zone used for 1-percent-annual-chance (base flood) floodplains that are determined for the Flood Insurance Study (FIS) by approximate methods of analysis. Because detailed hydraulic analyses are not performed for such areas, no Base Flood Elevations (BFEs) or depths are shown in this zone. Mandatory flood insurance purchase requirements apply. Zone AE and A1-A30 Zones AE and A1-A30 are the flood insurance rate zones used for the 1-percent-annual-chance floodplains that are determined for the FIS by detailed methods of analysis. In most instances, BFEs derived from the detailed hydraulic analyses are shown at selected intervals in this zone. Mandatory flood insurance purchase requirements apply. AE zones are areas of inundation by the 1-percent- annual-chance flood, including areas with the 2-percent wave runup, elevation less than 3.0 feet above the ground, and areas with wave heights less than 3.0 feet. These areas are subdivided into elevation zones with BFEs assigned. The AE zone will generally extend inland to the limit of the 1- percent-annual-chance Stillwater Flood Level (SWEL). Zone AH Zone AH is the flood insurance rate zone used for areas of 1-percent-annual-chance shallow flooding with a constant water-surface elevation (usually areas of ponding) where average depths are between 1 and 3 feet. -

Flood Fun Facts Be Prepared! Flood Insurance Building Smart Buying A

Flood Fun Facts Be Prepared! Building Smart • Flooding happens everywhere not just Sign up for Code Red today to get emergency The City of Venice regulates development in the the high-risk area calls and texts. For more information visit SFHA to reduce damage from future floods. • Six (6) inches of moving water can https://www.venicegov.com/government/fire/ There are many things you can do to lower knock over an adult, two (2) feet can weather-and-disaster-information/code-red your risk carry away a truck. You can also visit the City’s website to learn • Water can also • Elevate your new home or existing one how to prepare for a flood destroy a building and all of your equipment like water and an emergency supplies • One inch of water can heaters, A/C units and pool equipment list. cost $27,000 or more! above the base flood. Make sure you • Flood water is not get your permits from the Building clean. It may have Division first! mud, chemicals, road • Plan for proper drainage and design a oil, bacteria, viruses Flood Insurance rain garden and other health • Install flood vents in areas below the hazards. Talk to your insurance agent today to figure out base flood elevation • If you are in the Special Flood Hazard the best coverage for you. • For more information contact the Area (SFHA) there is a 25% chance of Condos and apartments may only cover the Building Division or Engineering Dept. flooding during a 30-year mortgage. common areas. Protect your space with Buying a fixer upper? • If you are outside of the SFHA there is a contents coverage. -

The Effects of Flood Insurance on Housing Markets

DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES IZA DP No. 11810 The Effects of Flood Insurance on Housing Markets Agustín Indaco Francesc Ortega Süleyman Taşpınar SEPTEMBER 2018 DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES IZA DP No. 11810 The Effects of Flood Insurance on Housing Markets Agustín Indaco The Graduate Center CUNY Francesc Ortega Queens College CUNY and IZA Süleyman Taşpınar Queens College CUNY SEPTEMBER 2018 Any opinions expressed in this paper are those of the author(s) and not those of IZA. Research published in this series may include views on policy, but IZA takes no institutional policy positions. The IZA research network is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity. The IZA Institute of Labor Economics is an independent economic research institute that conducts research in labor economics and offers evidence-based policy advice on labor market issues. Supported by the Deutsche Post Foundation, IZA runs the world’s largest network of economists, whose research aims to provide answers to the global labor market challenges of our time. Our key objective is to build bridges between academic research, policymakers and society. IZA Discussion Papers often represent preliminary work and are circulated to encourage discussion. Citation of such a paper should account for its provisional character. A revised version may be available directly from the author. IZA – Institute of Labor Economics Schaumburg-Lippe-Straße 5–9 Phone: +49-228-3894-0 53113 Bonn, Germany Email: [email protected] www.iza.org IZA DP No. 11810 SEPTEMBER 2018 ABSTRACT The Effects of Flood Insurance on Housing Markets We analyze the role of flood insurance on the housing markets of coastal cities. -

Help Clients Protect Their Investment

HELP CLIENTS PROTECT THEIR INVESTMENT QUESTIONS & ANSWERS ABOUT FLOOD INSURANCE FOR REAL ESTATE PROFESSIONALS Why should I talk to my Who can purchase clients about flood insurance? flood insurance? Flooding can happen anywhere at any Anyone in a community that participates time. You should encourage your clients to in the NFIP can purchase building and/ purchase flood insurance to protect their or contents coverage, with few exceptions. properties from flood damage and the Licensed insurance agents can tell you if economic devastation it can bring. a specific community participates in the NFIP. Coastal Barrier Resources System Areas (CBRS), undeveloped coastal A property does not have to be near areas established for wildlife refuge, water to flood. In fact, more than sanctuary, recreational, or natural resource 20 percent of all National Flood conservation purposes (Otherwise Protected Insurance Program (NFIP) flood Areas), and buildings principally below ground claims come from outside of the or entirely over water may not be eligible for areas at the highest risk for flood NFIP flood insurance coverage. (Special Flood Hazard Areas). Floods can result from storms, melting snow, hurricanes, drainage system backups, broken water mains, and changes to How do clients obtain land from new construction, among a flood insurance policy? other things. The NFIP also has resources to help your client find an agent. Your client can visit fema.gov/nfip or call their local insurance It is important to let your client know that agent for more information on purchasing a homeowner’s insurance policies typically policy. Your client can purchase NFIP flood do not cover floods.