The Threat of Surveillance Capitalism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

T H E N E T D E L U S Io N E V G E N Y M O R O Zo V

2/C PMS (BLACK + 809) SOFT-TOUCH MATTE LAMINATION + SPOT GLOSS THE NET DELUSION EVGENY MOROZOV POLITICS/TECHNOLOGY $27.95/$35.50 CAN “ Evgeny Morozov is wonderfully knowledgeable about the Internet—he seems “THE REVOLUTION WILL BE TWITTERED!” to have studied every use of it, or every political use, in every country in the declared journalist Andrew Sullivan after world (and to have read all the posts). And he is wonderfully sophisticated and protests erupted in Iran in June 2009. Yet for tough-minded about politics. This is a rare combination, and it makes for a all the talk about the democratizing power powerful argument against the latest versions of technological romanticism. of the Internet, regimes in Iran and China His book should be required reading for every political activist who hopes to are as stable and repressive as ever. In fact, ALEXANDER KRSTEVSKI ALEXANDER change the world on the Internet.” —MICHAEL WALZER, Institute for authoritarian governments are effectively Advanced Study, Princeton using the Internet to suppress free speech, EVGENY MOROZOV hone their surveillance techniques, dissem- is a contributing editor to Foreign Policy “ Evgeny Morozov has produced a rich survey of recent history that reminds us inate cutting-edge propaganda, and pacify and Boston Review and a Schwartz Fellow that everybody wants connectivity but also varying degrees of control over their populations with digital entertain- at the New American Foundation. Morozov content, and that connectivity on its own is a very poor predictor of political ment. Could the recent Western obsession is currently also a visiting scholar at Stan- pluralism... -

Surveillance Capitalism and Privacy. Knowledge and Attitudes on Surveillance Capitalism and Online Institutional Privacy Protect

CORE brought to you by Pobrane z czasopisma Mediatizations Studies http://mediatization.umcs.pl Data: 20/11/2019 22:16:21 MEDIATIZATION STUDIES 2/2018 DOI: 10.17951/ms.2018.2.49-68 GRZEGORZ PTASZEK View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk AGH UNIVERSITY OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY [email protected] Surveillance capitalism and privacy. Knowledge and attitudes on surveillance capitalism and online institutional privacy protection practices among adolescents in Poland Abstract. The purpose of the study was to determine the level of knowledge and attitudes towards surveillance capitalism and online institutional privacy protection practices among adolescents in Poland (aged 18–19), as well as to determine the relationships between these variables. Surveillance capitalism has emerged as a result of internet users’ activities and involves the collection of all data about these users by different entities for speciic beneits without letting them know about it. The dominantrole in surveillance capitalism is played by hi-tech corporations. The aim of the study was to verify whether knowledge, and what kind of knowledge, on surveillance capitalism translates into practices related to the protection of online institutional privacy. The study was conducted on a sample of 177 adolescents in Poland. The main part of theUMCS questionnaire consisted of two scales: the scale of knowledge and attitudes on surveillance capitalism, and the scale of online institutional privacy protection practices. The results of the study, calculated by statistical methods, showed that although the majority of respondents had average knowledge and attitudes about surveillance capitalism, which may result from insuficient knowledge of the subject matter, this participation in specialized activities/workshops inluences the level of intensiication of online institutional privacy protection practices. -

The Net Delusion: the Dark Side of Internet Freedom

The Net Delusion: The Dark Side of Internet Freedom http://www.carnegiecouncil.org/resources/transcripts/0349.html/:pf_print... The Net Delusion: The Dark Side of Internet Freedom Evgeny Morozov , Joanne J. Myers Tuesday, January 25, 2011 Introduction Remarks Questions and Answers Introduction JOANNE MYERS: I'm Joanne Myers, director of Public Affairs Programs, and on behalf of the Carnegie Council, I'd like to thank you all for joining us. If you have been following the news out of Tunisia and are interested in the idea of democracy promotion via the Internet, you will find today's discussion to be extremely interesting. The question our speaker will be addressing is about whether the increased The Net Delusion: The Dark use of the Internet and technological innovations such as Twitter, YouTube, and Facebook Side of Internet Freedom have, in reality, brought increased democracy to those under authoritarian rule—or have these new cyber tools actually made things worse? Evgeny Morozov is often described as a gifted young cyber policy scholar who made his way to America from Belarus. He is recognized as the expert on the interaction of digital technology and democracy. In fact, his writings on this topic have reshaped many foreign policy debates and initiated new thinking on the power of the Internet to promote democracy around the world. In writing this book, Mr. Morozov's aim is to bring a dose of realpolitik to discussions about how much of a difference the Net and digital technologies actually make in advancing democracy and freedom. His findings may surprise you. -

361-Emerald Gottlieb-3611585 BIB 181..191

REFERENCES Agamben, G. (2015). The use of bodies (A. Kostko, Trans.). Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. Babe, R. (2010). Cultural studies and political economy: Toward a new integration. Toronto, ON: Lexington Books. Barad, K. (2003). Posthumanist performativity: Toward an understanding of how matter comes to matter. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 28(3) (Spring), 801À831. Barad, K. (2007). Meeting the universe half-way. Durham, NC: Duke U. Press. Bataille, G. (1985). Visions of excess (A. Stoekl, Trans.). Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press. Benjamin, W. (1969). Illuminations (H. Arendt, Trans.). New York, NY: Schocken Books. Bernes, J. (2013). Logistics, counter-logistics and the commu- nist prospect. Endnotes, Vol. 3, Endnotes, London. Retrieved from https://endnotes.org.uk/en/jasper-bernes-logisticscoun- terlogistics-and-the-communist-prospect BIPM Bureau International des Poids et Mesures. (2008). The International System of Units (SI). Paris: STEDI Media. Bratton, B. (2015). The stack. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. 181 182 References Braverman, H. (1998). Labor and monopoly capital. New York, NY: Monthly Review Press. Bridle, J. (2016). Cloud history, cloud thinking. London: Serpentine Galleries, September 2016. Retrieved from http:// cloudindx.com Brustein, J. (2016). Uber and Lyft want to replace public buses. Bloomberg.com, August 15. Retrieved from https:// www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2016-08-15/uber-and- lyft-want-to-replace-public-buses Caffentzis, G. (2013). In letters of blood and fire. Oakland, CA: PM Press. Caliskan, A., Bryson, J., & Narayanan, A. (April 14 2017). Semantics derived automatically from language corpora contain human-like biases. Science 356(6334), 183À186. Callinikos, A. -

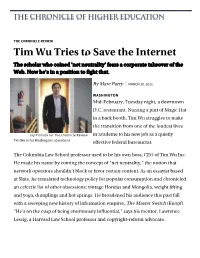

Tim Wu Tries to Save the Internet the Scholar Who Coined 'Net Neutrality' Fears a Corporate Takeover of the Web

THE CHRONICLE REVIEW Tim Wu Tries to Save the Internet The scholar who coined 'net neutrality' fears a corporate takeover of the Web. Now he's in a position to fight that. By Marc Parry MARCH 20, 2011 WASHINGTON Mid-February, Tuesday night, a downtown D.C. restaurant. Nursing a pint of Magic Hat in a back booth, Tim Wu struggles to make the transition from one of the loudest lives Jay Primack for The Chronicle Review in academe to his new job as a quietly Tim Wu in his Washington apartment effective federal bureaucrat. The Columbia Law School professor used to be his own boss, CEO of Tim Wu Inc. He made his name by coining the concept of "net neutrality," the notion that network operators shouldn't block or favor certain content. As an essayist based at Slate, he translated technology policy for popular consumption and chronicled an eclectic list of other obsessions: vintage Hondas and Mongolia, weight lifting and yoga, dumplings and hot springs. He broadened his audience this past fall with a sweeping new history of information empires, The Master Switch (Knopf). "He's on the cusp of being enormously influential," says his mentor, Lawrence Lessig, a Harvard Law School professor and copyright-reform advocate. Maybe. But right now Wu is trying to be something else: boring. One day before this dinner interview, the 38-year-old professor reported for duty as a senior adviser at the Federal Trade Commission, a consumer-protection and antitrust- enforcement agency with a mandate to fight business abuses. So he clams up when I ask what must be on the minds of many tech lobbyists in town: Which company scares you the most? "I can't answer that question, now I'm in the FTC," Wu says. -

Privacy Trading in the Surveillance Capitalism Age Viewpoints on ‘Privacy-Preserving’ Societal Value Creation

Privacy Trading in the Surveillance Capitalism Age Viewpoints on ‘Privacy-Preserving’ Societal Value Creation Ranjan Pal, Jon Crowcroft University of Cambridge [email protected],[email protected],[email protected] This article is an editorial note submitted to CCR. It has NOT been peer reviewed. The authors take full responsibility for this article’s technical content. Comments can be posted through CCR Online. ABSTRACT well as the state-of-the-art IoT/CPS systems. All this is made possi- In the modern era of the mobile apps (part of the era of surveil- ble through mobile apps (applications) that enable the functioning lance capitalism, a famously coined term by Shoshana Zuboff), huge of operations in this ecosystem. ln-app advertising is an essential quantities of data about individuals and their activities offer a wave part of this digital ecosystem of free mobile applications, where of opportunities for economic and societal value creation. How- the ecosystem entities comprise the consumers, consumer apps, ever, the current personal data ecosystem is mostly de-regulated, ad-networks, advertisers, and retailers (see Figure 1 for a simplified fragmented, and inefficient. On one hand, end-users are often not representation for the ad-network and advertisers case). In reality, able to control access (either technologically, by policy, or psycho- advertisers and retailers could be directly linked to the consumer logically) to their personal data which results in issues related to apps in sell-buy relationships. As a popular example, Evite.com privacy, personal data ownership, transparency, and value distri- may sell lists of their consumers attending a party in a given loca- bution. -

Surveillance Capitalism - Shoshana Zuboff Wenhao & Sofia & Anvitha

Surveillance Capitalism - Shoshana Zuboff Wenhao & Sofia & Anvitha Introduction Wenhao Author: Shoshana Zuboff • Professor of Business Administration, Harvard Business School • Defined the concept of Surveillance Capitalism • International Conference on Information Systems Scholars' 2016 Best Paper Award Image. https://www.hachettebookgroup.com/contributor/shoshana-zuboff/ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shoshana_Zuboff Intro - “Big Data” Image. https://hackernoon.com/the-3-vs-of-big-data-analytics-1afd59692adb “Big Data”: General Definition • Big Data is also data but with a huge size. • Huge in volume and growing exponentially with time. • Too large and complex that no traditional data management tools are able to store it or process it efficiently. • E.g. Trade data (New York Stock Exchange) Video, photo, messages, comments (Social Media) Snijders, C.; Matzat, U.; Reips, U.-D. (2012). "'Big Data': Big gaps of knowledge in the field of Internet". “Big Data”: Features • Delineated by Constantiou and Kallinikos (2014) • Heterogeneous: high variability of data types • Unstructured: no fixed format • Trans-semiotic: extend beyond alphanumeric systems • Decontextualized: surrounding context removed • Agnostic: may being produced for purposes different from those sought by big data crunching Constantiou, I.D. and Kallinikos, J.(2014). New Games, New Rules: Big data and the changing context of strategy Applications in Daily Life • Media and Entertainment Industry • Collect personal browsing data => Recommendation System • E.g. Spotify, YouTube, Amazon Prime Image. https://medium.com/s/story/spotifys-discover-weekly-how-machine-learning-finds-your-new-music-19a41ab76efe Applications in Daily Life • Health Care via wearable devices • Collect personal health record => Detecting possible diseases • E.g. Apple Watch Image. https://www.macrumors.com/2019/01/08/cook-apple-health-most-important-contribution-to-mankind/ Applications in Daily Life • Advertisement • Collect personal searching data => Personalized advertising • E.g. -

Efficiency and Madness Using Data and Technology Environmental to Solve Social, and Political Problems

Efficiency and Madness Madness Efficiencyand More and more, digital technologies and data are being relied upon to solve the world’s biggest pro- Efficiency anda M dness blems. Sometimes referred to as ‘technofixes’, these Using Data and Technology to Solve Social, Environmental data-driven technologies are applied to social, and Political Problems political and environmental challenges around the world. But their implementation can create both triumphs and disasters. Using Data and Technology to Solve Solve to Technology and Data Using We need to find a constructive way to critique these technofixes – one that acknowledges both their utopian and dystopian potential and the trade-offs they present. This is a call to action, for techies and non-techies alike, to find new ways of thinking about data-driven technologies and how they are changing our societies. Social, Environmental and Political Problems Political and Social, Environmental Stephanie Hankey and Marek Tuszynski Rz_Cover_Efficiency and Madness.indd 1 02.10.17 11:57 Efficiency and Madness Using Data and Technology to Solve Social, Environmental and Political Problems by Stephanie Hankey & Marek Tuszynski Supported by the Heinrich Böll Foundation With contributions from Etienne Turpin Support by Gary Wright Copy editing by Christy Lange Cover design by Ingo Diekhaus With special thanks to Christine Chemnitz, Susanne Diehr, Lili Fuhr, Jörg Haas, Annette Kraus, Heike Löschmann, Linda Schneider and Barbara Unmüßig. Interior_pages.indd 2 02/10/2017 10:46 Efficiency and Madness Using Data and Technology to Solve Social, Environmental and Political Problems Interior_pages.indd 3 02/10/2017 10:46 Interior_pages.indd 4 02/10/2017 10:46 5 Introduction Technology as Magic and Loss Technologies help us do more with less, they defy boundaries of space, time and self. -

The Law of Informational Capitalism

AMY KAPCZYNSKI The Law of Informational Capitalism The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power BY SHOSHANA ZUBOFF PUBLICAFFAIRS, 2019 Between Truth and Power: The Legal Constructions of Informational Capitalism BY JULIE E. COHEN OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS, 2019 abstract. Over the past several decades, our capacity to technologically process and ex- change data and information has expanded dramatically. An early sense of optimism about these developments has given way to widespread pessimism, in the wake of a wave of revelations about the extent of digital tracking and manipulation. Shoshana Zuboff’s book, The Age of Surveillance Capitalism, has been hailed by many as the decisive account of the looming threat of private power in the digital age. While the book offers important insights, Zuboff’s account is too narrow: it fixates on technological threats to our autonomy and obscures the relationship between technology and the problems of monopoly, inequality, and discriminatory hierarchy that threaten our democ- racy. Zuboff’s book also fails to appreciate the critical role that law plays in the construction and persistence of private power. Julie Cohen’s book, Between Truth and Power: The Legal Constructions of Informational Capitalism, gives us a much better framework to comprehend intensifying forms of private power today and the role that law has played in supporting them. Drawing on Cohen’s insights, I construct an account of the “law of informational capitalism,” with particular attention to the law that undergirds platform power. Once we come to see informational capitalism as con- tingent upon specific legal choices, we can begin to consider how democratically to reshape it. -

Shoshana Zuboff: Secrets of Surveillance Capitalism

Shoshana Zuboff: Secrets of Surveillance Capitalism https://www.faz.net/aktuell/feuilleton/debatten/the-digital-debate/shos... 03.03.2016 - Aktualisiert: 05.03.2016, 13:23 Uhr https://www.faz.net/-hzi-8eaf4 Google as a Fortune Teller Governmental control is nothing compared to what Google is up to. The company is creating a wholly new genus of capitalism, a systemic coherent new logic of accumulation we should call surveillance capitalism. Is there nothing we can do?surveillance capitalism Von SHOSHANA ZUBOFF © ddp images The assault we face is driven by the exceptional appetites of a wholly new genus of capitalism: surveillance capitalism. Google surpassed Apple as the world’s most highly valued company in January for the first time since 2010. (Back then each company was worth less than 200 billion. Now each is valued at well over 500 billion.) While Google’s new lead lasted only a few days, the company’s success has implications for everyone who lives within the reach of the Internet. Why? Because Google is ground zero for a wholly new subspecies of capitalism in which profits derive from the unilateral surveillance and modification of human behavior. This is a new surveillance capitalism that is unimaginable outside the inscrutable high velocity circuits of Google’s digital universe, whose signature feature is the Internet and its successors. While the world is riveted by the showdown between Apple and the FBI, the real truth is that the surveillance capabilities being developed by surveillance capitalists are the envy of every state security agency. What are the secrets of this new capitalism, how do they produce such staggering wealth, and how can we protect ourselves from its invasive power? (German Version: „Wie wir Sklaven von Google wurden“ von Shoshana Zuboff) “Most Americans realize that there are two groups of people who are monitored regularly as they move about the country. -

Surveillance Capitalism

Journal of Technology Law & Policy Volume 25 Issue 1 Article 3 Surveillance Capitalism William Hamilton Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.ufl.edu/jtlp Part of the Privacy Law Commons, and the Science and Technology Law Commons Recommended Citation Hamilton, William () "Surveillance Capitalism," Journal of Technology Law & Policy: Vol. 25 : Iss. 1 , Article 3. Available at: https://scholarship.law.ufl.edu/jtlp/vol25/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UF Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Technology Law & Policy by an authorized editor of UF Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SURVEILLANCE CAPITALISM William Hamilton* In 2019, Harvard Business School Professor Shoshana Zuboff published The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power.1 What I hope to accomplish in this short presentation is to unpack some of the salient themes of this interesting, important book. I believe her book will lend context and urgency to this conference. Her book is a combination of excellent research, journalism, and scholarship. It is also a call, a plea, a supplication. Thus, the sub-title, The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power, presages an unrelenting critical study of the deployment of a new economic power in the early 21st century. However, a word of warning and a plea from me for indulgence. Surveillance Capitalism is a tour de force consisting of 525 pages of relatively small font text and over 100 pages of even smaller font footnotes. -

Socialize the Data Centres!

New Masses, New Media—5 evgeny morozov SOCIALIZE THE DATA CENTRES! Your work traces a distinctive path—unlike that of any other technology critic—from a grounding in the politics of post-Cold War Eastern Europe, via critique of Silicon Valley patter, to socio-historical debates around the rela- tions between the Internet and neoliberalism. What was the background that produced this evolution? was born in 1984, in the Minsk region of Belarus, in a new min- ing town called Soligorsk, founded in the late fifties. More or less the whole labour force was brought in from outside, and there’s little sense of national belonging. My father’s family came from Ithe north of Russia; my mother, who was born near Moscow, arrived in the seventies with a degree in mining from Ukraine. The town is dominated by one huge state-owned enterprise that mines potassium and produces fertilizers which sell very well on the world market: it’s still the most profitable company in Belarus. My entire family worked for it, from grandparents to uncles and aunts. The ussr dissolved when I was seven, and while there may have been all sorts of problems with living in a small city like Soligorsk, they were not linked to the ussr’s disappearance. Under Lukashenko, who came to power when I was ten, Belarus was officially bilingual, but Russian was the dominant language, and growing up in Soligorsk felt just like being in a province of Russia. We were much more connected to events in Moscow than in Minsk. Initially there was no Belarusian television; the national media were not very strong, so the newspapers we got, and most of the tv programmes new left review 91 jan feb 2015 45 46 nlr 91 we watched at home, were Russian.