R2P and the Arab Spring: Norm Localisation and the US Response to the Early Syria Crisis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gitmo Hs Doc3

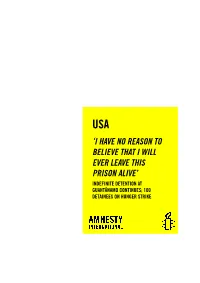

USA ‘I HAVE NO REASON TO BELIEVE THAT I WILL EVER LEAVE THIS PRISON ALIVE’ INDEFINITE DETENTION AT GUANTÁNAMO CONTINUES; 100 DETAINEES ON HUNGER STRIKE Amnesty International Publications First published in May 2013 by Amnesty International Publications International Secretariat Peter Benenson House 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW United Kingdom www.amnesty.org Copyright Amnesty International Publications 2013 Index: AMR 51/022/2013 Original Language: English Printed by Amnesty International, International Secretariat, United Kingdom All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the publishers. Amnesty International is a global movement of 3 million people in more than 150 countries and territories, who campaign on human rights. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights instruments. We research, campaign, advocate and mobilize to end abuses of human rights. Amnesty International is independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion. Our work is largely financed by contributions from our membership and donations Table of Contents ‘It is not a surprise to me that we’ve got problems in Guantánamo’ .................................... 1 History of a hunger striker ............................................................................................ -

US-China Relations

U.S.-China Relations: An Overview of Policy Issues Susan V. Lawrence Specialist in Asian Affairs August 1, 2013 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov R41108 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress U.S.-China Relations: An Overview of Policy Issues Summary The United States relationship with China touches on an exceptionally broad range of issues, from security, trade, and broader economic issues, to the environment and human rights. Congress faces important questions about what sort of relationship the United States should have with China and how the United States should respond to China’s “rise.” After more than 30 years of fast-paced economic growth, China’s economy is now the second-largest in the world after that of the United States. With economic success, China has developed significant global strategic clout. It is also engaged in an ambitious military modernization drive, including development of extended-range power projection capabilities. At home, it continues to suppress all perceived challenges to the Communist Party’s monopoly on power. In previous eras, the rise of new powers has often produced conflict. China’s new leader Xi Jinping has pressed hard for a U.S. commitment to a “new model of major country relationship” with the United States that seeks to avoid such an outcome. The Obama Administration has repeatedly assured Beijing that the United States “welcomes a strong, prosperous and successful China that plays a greater role in world affairs,” and that the United States does not seek to prevent China’s re-emergence as a great power. -

The Obama Administration and the Prospects for a Democratic Presidency in a Post-9/11 World

NYLS Law Review Vols. 22-63 (1976-2019) Volume 56 Issue 1 Civil Liberties 10 Years After 9/11 Article 2 January 2012 The Obama Administration and the Prospects for a Democratic Presidency in a Post-9/11 World Peter M. Shane The Ohio State University Moritz College of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.nyls.edu/nyls_law_review Part of the Law and Politics Commons, Law and Society Commons, Military, War, and Peace Commons, and the National Security Law Commons Recommended Citation Peter M. Shane, The Obama Administration and the Prospects for a Democratic Presidency in a Post-9/11 World, 56 N.Y.L. SCH. L. REV. 28 (2011-2012). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@NYLS. It has been accepted for inclusion in NYLS Law Review by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@NYLS. VOLUME 56 | 2011/12 PETER M. SHANE The Obama Administration and the Prospects for a Democratic Presidency in a Post-9/11 World ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Jacob E. Davis and Jacob E. Davis II Chair in Law, The Ohio State University Moritz College of Law. 27 THE PROSpeCTS FOR A DemoCRATIC PRESIdeNCY IN A POST-9/11 WORld [W]hen I won [the] election in 2008, one of the reasons I think that people were excited about the campaign was the prospect that we would change how business is done in Washington. And we were in such a hurry to get things done that we didn’t change how things got done. And I think that frustrated people. -

The Anglo-America Special Relationship During the Syrian Conflict

Open Journal of Political Science, 2019, 9, 72-106 http://www.scirp.org/journal/ojps ISSN Online: 2164-0513 ISSN Print: 2164-0505 Beyond Values and Interests: The Anglo-America Special Relationship during the Syrian Conflict Justin Gibbins1, Shaghayegh Rostampour2 1Zayed University, Dubai, UAE 2Brandeis University, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA How to cite this paper: Gibbins, J., & Abstract Rostampour, S. (2019). Beyond Values and Interests: The Anglo-America Special Rela- This paper attempts to reveal how intervention in international conflicts (re) tionship during the Syrian Conflict. Open constructs the Anglo-American Special Relationship (AASR). To do this, this Journal of Political Science, 9, 72-106. https://doi.org/10.4236/ojps.2019.91005 article uses Syria as a case study. Analyzing parliamentary debates, presiden- tial/prime ministerial speeches and formal official addresses, it offers a dis- Received: November 26, 2018 cursive constructivist analysis of key British and US political spokespeople. Accepted: December 26, 2018 We argue that historically embedded values and interests stemming from un- Published: December 29, 2018 ity forged by World War Two have taken on new meanings: the AASR being Copyright © 2019 by authors and constructed by both normative and strategic cultures. The former, we argue, Scientific Research Publishing Inc. continues to forge a common alliance between the US and Britain, while the This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International latter produces notable tensions between the two states. License (CC BY 4.0). http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Keywords Open Access Anglo-American, Special Relationship, Discourse, Intervention, Conflict 1. Introduction At various times in its protracted history, the Anglo-American Special Rela- tionship1 has waxed and waned in its potency since Winston Churchill’s first usage. -

The United States Government Manual 2009/2010

The United States Government Manual 2009/2010 Office of the Federal Register National Archives and Records Administration The artwork used in creating this cover are derivatives of two pieces of original artwork created by and copyrighted 2003 by Coordination/Art Director: Errol M. Beard, Artwork by: Craig S. Holmes specifically to commemorate the National Archives Building Rededication celebration held September 15-19, 2003. See Archives Store for prints of these images. VerDate Nov 24 2008 15:39 Oct 26, 2009 Jkt 217558 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 6996 Sfmt 6996 M:\GOVMAN\217558\217558.000 APPS06 PsN: 217558 dkrause on GSDDPC29 with $$_JOB Revised September 15, 2009 Raymond A. Mosley, Director of the Federal Register. Adrienne C. Thomas, Acting Archivist of the United States. On the cover: This edition of The United States Government Manual marks the 75th anniversary of the National Archives and celebrates its important mission to ensure access to the essential documentation of Americans’ rights and the actions of their Government. The cover displays an image of the Rotunda and the Declaration Mural, one of the 1936 Faulkner Murals in the Rotunda at the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) Building in Washington, DC. The National Archives Rotunda is the permanent home of the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution of the United States, and the Bill of Rights. These three documents, known collectively as the Charters of Freeedom, have secured the the rights of the American people for more than two and a quarter centuries. In 2003, the National Archives completed a massive restoration effort that included conserving the parchment of the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, and the Bill of Rights, and re-encasing the documents in state-of-the-art containers. -

Administration of Barack Obama, 2014 Remarks on the Resignation Of

Administration of Barack Obama, 2014 Remarks on the Resignation of James F. "Jay" Carney as White House Press Secretary and the Appointment of Joshua R. Earnest as White House Press Secretary May 30, 2014 [The President interrupted a press briefing by Press Secretary Carney.] The President. Hello. You haven't seen me enough today. One of Jay's favorite lines is, "I have no personnel announcements at this time." But I do. And it's bittersweet. It involves one of my closest friends here in Washington. In April, Jay came to me in the Oval Office and said he was thinking about moving on, and I was not thrilled, to say the least. But Jay has had to wrestle with this decision for quite some time. He has been on my team since day one: for 2 years with the Vice President, for the past 3 ½ years as my Press Secretary. And it has obviously placed a strain on Claire, his wife, and his two wonderful kids Hugo and Della. Della's Little League team, by the way, I had a chance to see the other day, and she's a fine pitcher. But he wasn't seeing enough of the games. Jay was a reporter for 21 years before coming to the White House, including a stint as Moscow bureau chief for Time magazine during the collapse of the Soviet empire. So he comes to this place with a reporter's perspective. That's why, believe it or not, I actually think he will miss hanging out with all of you, including the guys in the front row. -

Administration of Barack Obama, 2012 the President's News Conference

Administration of Barack Obama, 2012 The President's News Conference in Chicago, Illinois May 21, 2012 The President. Good afternoon, everybody. Let me begin by saying thank you to my great friend Rahm Emanuel, the mayor of the city of Chicago, and to all my neighbors and friends, the people of the city of Chicago, for their extraordinary hospitality and for everything that they've done to make this summit such a success. I could not be prouder to welcome people from around the world to my hometown. This was a big undertaking, some 60 world leaders, not to mention folks who were exercising their freedom of speech and assembly, the very freedoms that our alliance are dedicated to defending. And so it was a lot to carry for the people of Chicago, but this is a city of big shoulders. Rahm, his team, Chicagoans proved that this world-class city knows how to put on a world-class event. And partly, this was a perfect city for this summit because it reflected the bonds between so many of our countries. For generations, Chicago has welcomed immigrants from around the world, including an awful lot of our NATO allies. And I'd just add that I have lost track of the number of world leaders and their delegations who came up to me over the last day and a half and remarked on what an extraordinarily beautiful city Chicago is. And I could not agree more. I am especially pleased that I had a chance to show them Soldier Field. -

Administration of Barack Obama, 2014 Checklist of White House Press

Administration of Barack Obama, 2014 Checklist of White House Press Releases December 31, 2014 The following list contains releases of the Office of the Press Secretary that are neither printed items nor covered by entries in the Digest of Other White House Announcements. Released January 1 Statement by National Economic Council Director Eugene B. Sperling on the need for congressional action to extend emergency unemployment benefits Released January 3 Fact sheet: Strengthening the Federal Background Check System To Keep Guns Out of Potentially Dangerous Hands Released January 5 Text of a readout of Deputy National Security Adviser Antony J. Blinken's telephone conversation with National Security Adviser Faleh al-Fayyad of Iraq Released January 6 Transcript of a press briefing by Press Secretary James F. "Jay" Carney and National Economic Council Director Eugene B. Sperling Released January 7 Transcript of a press briefing by Press Secretary James F. "Jay" Carney Released January 8 Transcript of a press briefing by Press Secretary James F. "Jay" Carney Released January 9 Transcript of a press briefing by Press Secretary James F. "Jay" Carney Statement by the Press Secretary: Obama Administration Launches Quadrennial Energy Review Statement by National Security Adviser Susan E. Rice on the situation in South Sudan Fact sheet: President Obama's Promise Zones Initiative Released January 10 Transcript of a press briefing by Press Secretary James F. "Jay" Carney Statement by Council of Economic Advisers Chairman Jason L. Furman on the employment situation in December Released January 12 Statement from the Office of the Vice President: President Obama Announces Presidential Delegation to the State of Israel To Attend the State Funeral of Former Prime Minister Ariel Sharon 1 Released January 13 Transcript of a press briefing by Press Secretary James F. -

Administration of Barack Obama, 2013 Checklist of White House Press Releases December 31, 2013 Released January 1 Released Janua

Administration of Barack Obama, 2013 Checklist of White House Press Releases December 31, 2013 The following list contains releases of the Office of the Press Secretary that are neither printed items nor covered by entries in the Digest of Other White House Announcements. Released January 1 Fact sheet: The Tax Agreement: A Victory for Middle-Class Families and the Economy Released January 2 Statement by the Press Secretary announcing that the President signed H.R. 4310 Statement by the Press Secretary announcing that the President signed H.R. 8 Released January 4 Text: Statement by Council of Economic Advisers Chairman Alan B. Krueger on the employment situation in December 2012 Released January 6 Statement by the Press Secretary announcing that the President signed H.R. 41 Released January 7 Transcript of a press briefing by Press Secretary James F. "Jay" Carney Released January 8 Transcript of a press briefing by Press Secretary James F. "Jay" Carney Transcript of an on-the-record conference call by Deputy National Security Adviser for Strategic Communications Benjamin J. Rhodes and Deputy Assistant to the President and Coordinator for South Asia Douglas E. Lute on Afghan President Hamid Karzai's upcoming visit to the White House Released January 9 Transcript of a press briefing by Press Secretary James F. "Jay" Carney Released January 10 Statement by the Press Secretary announcing that the President signed H.R. 1339, H.R. 1845, H.R. 2338, H.R. 3263, H.R. 3641, H.R. 3869, H.R. 3892, H.R. 4053, H.R. 4057, H.R. 4073, H.R. -

Appendix C—Checklist of White House Press Releases

Appendix C—Checklist of White House Press Releases The following list contains releases of the Office Released January 11 of the Press Secretary that are neither printed items nor covered by entries in the Digest of Transcript of a press gaggle by Principal Depu- Other White House Announcements. ty Press Secretary Joshua R. Earnest Released January 3 Statement by the Press Secretary: President Obama Issues Call to Action To Invest in Transcript of a press briefing by Press Secre- America at White House “Insourcing Ameri- tary James F. “Jay” Carney can Jobs” Forum Statement by the Press Secretary announcing Advance text of the President’s remarks at the that the President signed H.R. 515, H.R. 789, White House Insourcing American Jobs Fo- H.R. 1059, H.R. 1264, H.R. 1801, H.R. 1892, rum H.R. 2056, H.R. 2422, and H.R. 2845 Released January 12 Released January 4 Transcript of a press briefing by Press Secre- Transcript of a press gaggle by Press Secretary tary James F. “Jay” Carney James F. “Jay” Carney Released January 13 Statement by the Press Secretary: We Can’t Wait: The White House Announces Federal Transcript of a press gaggle by Press Secretary and Private Sector Commitments To Provide James F. “Jay” Carney and Office of Manage- Employment Opportunities for Nearly 180,000 ment and Budget Deputy Director for Man- Youth (released January 4; embargoed until agement Jeffrey D. Zients January 5) Statement by the Press Secretary: President Advance text of the President’s remarks at Shak- Obama Announces Proposal To Reform, Reor- er Heights High School in Shaker Heights, OH ganize and Consolidate Government Released January 5 Advance text of the President’s remarks on Transcript of a press briefing by Press Secre- Government reform tary James F. -

Administration of Barack Obama, 2012 Checklist of White House Press

Administration of Barack Obama, 2012 Checklist of White House Press Releases December 31, 2012 The following list contains releases of the Office of the Press Secretary that are neither printed items nor covered by entries in the Digest of Other White House Announcements. Released January 3 Transcript of a press briefing by Press Secretary James F. "Jay" Carney Statement by the Press Secretary announcing that the President signed H.R. 515, H.R. 789, H.R. 1059, H.R. 1264, H.R. 1801, H.R. 1892, H.R. 2056, H.R. 2422, and H.R. 2845 Released January 4 Transcript of a press gaggle by Press Secretary James F. "Jay" Carney Statement by the Press Secretary: We Can't Wait: The White House Announces Federal and Private Sector Commitments To Provide Employment Opportunities for Nearly 180,000 Youth (embargoed until January 5) Advance text of the President's remarks at Shaker Heights High School in Shaker Heights, OH Released January 5 Transcript of a press briefing by Press Secretary James F. "Jay" Carney Advance text of the President's remarks in Arlington, VA Released January 6 Text: Statement by Council of Economic Advisers Chairman Alan B. Krueger on the employment situation in December 2011 Released January 9 Transcript of a press briefing by Press Secretary James F. "Jay" Carney Released January 10 Transcript of a press briefing by Press Secretary James F. "Jay" Carney Released January 11 Transcript of a press gaggle by Principal Deputy Press Secretary Joshua R. Earnest Statement by the Press Secretary: President Obama Issues Call to Action To Invest in America at White House "Insourcing American Jobs" Forum Advance text of the President's remarks at the White House Insourcing American Jobs Forum Released January 12 Transcript of a press briefing by Press Secretary James F. -

Vice President Joe Biden

Please join BOB BAUER | SARAH BIANCHI | TONY BLINKEN MICHAEL BOSWORTH | WILLIAM BURNS | JAY CARNEY MARK CHILDRESS | JIM COLE | STEVE CROLEY | WILLIAM DALEY TOM DONILON | ANITA DUNN | ALASTAIR FITZPAYNE ANTHONY FOXX | MICHAEL FROMAN | BRETT HOLMGREN DANA HYDE | JENNIFER KLEIN | NEIL MACBRIDE ALEJANDRO MAYORKAS | KARI MCDONOUGH | NICK MCQUAID LISA MONACO | SARAH MORGENTHAU | TOM NIDES | DAVID OGDEN NATALIE QUILLIAN | DANA REMUS | PETER ROUSE | KATHY RUEMMLER RAJIV SHAH | TODD STERN | STEVE VANROEKEL | DON VERRILLI SALLY YATES | JEFF ZIENTS for a reception with VICE PRESIDENT JOE BIDEN Wednesday, November 6 Home of Mary & Jeff Zients 6:30pm | Washington, DC Please click here to RSVP or to contribute online: https://secure.joebiden.com/onlineactions/8qGB_PjBbEKE-z1cD8v7mQ2 For more information contact Sanam Rastegar [email protected] | 203.984.4236 Contributions to Biden For President are not deductible as charitable contributions for Federal income tax purposes. The campaign does not accept contributions from corporations or their PACs; unions; federal government contractors; national banks; those registered as federal lobbyists or under the Foreign Agents Registration Act; SEC-named executives of fossil fuel companies (i.e., companies whose primary business is the extraction, processing, distribution or sale of oil, gas or coal); or foreign nationals. To comply with Federal law, we must use our best efforts to obtain, maintain, and submit the name, mailing address, occupation and name of the employer of individuals whose contributions exceed $200 per election. By providing your mobile phone number you consent to receive recurring text messages from Biden for President. Message & Data Rates May Apply. Text HELP for Info. Text STOP to opt out.