Iglulik Inuit Drum Dance: Past, Present, and Future

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Of the Inuit Bowhead Knowledge Study Nunavut, Canada

english cover 11/14/01 1:13 PM Page 1 FINAL REPORT OF THE INUIT BOWHEAD KNOWLEDGE STUDY NUNAVUT, CANADA By Inuit Study Participants from: Arctic Bay, Arviat, Cape Dorset, Chesterfield Inlet, Clyde River, Coral Harbour, Grise Fiord, Hall Beach, Igloolik, Iqaluit, Kimmirut, Kugaaruk, Pangnirtung, Pond Inlet, Qikiqtarjuaq, Rankin Inlet, Repulse Bay, and Whale Cove Principal Researchers: Keith Hay (Study Coordinator) and Members of the Inuit Bowhead Knowledge Study Committee: David Aglukark (Chairperson), David Igutsaq, MARCH, 2000 Joannie Ikkidluak, Meeka Mike FINAL REPORT OF THE INUIT BOWHEAD KNOWLEDGE STUDY NUNAVUT, CANADA By Inuit Study Participants from: Arctic Bay, Arviat, Cape Dorset, Chesterfield Inlet, Clyde River, Coral Harbour, Grise Fiord, Hall Beach, Igloolik, Iqaluit, Kimmirut, Kugaaruk, Pangnirtung, Pond Inlet, Qikiqtarjuaq, Rankin Inlet, Nunavut Wildlife Management Board Repulse Bay, and Whale Cove PO Box 1379 Principal Researchers: Iqaluit, Nunavut Keith Hay (Study Coordinator) and X0A 0H0 Members of the Inuit Bowhead Knowledge Study Committee: David Aglukark (Chairperson), David Igutsaq, MARCH, 2000 Joannie Ikkidluak, Meeka Mike Cover photo: Glenn Williams/Ursus Illustration on cover, inside of cover, title page, dedication page, and used as a report motif: “Arvanniaqtut (Whale Hunters)”, sc 1986, Simeonie Kopapik, Cape Dorset Print Collection. ©Nunavut Wildlife Management Board March, 2000 Table of Contents I LIST OF TABLES AND FIGURES . .i II DEDICATION . .ii III ABSTRACT . .iii 1 INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 RATIONALE AND BACKGROUND FOR THE STUDY . .1 1.2 TRADITIONAL ECOLOGICAL KNOWLEDGE AND SCIENCE . .1 2 METHODOLOGY 3 2.1 PLANNING AND DESIGN . .3 2.2 THE STUDY AREA . .4 2.3 INTERVIEW TECHNIQUES AND THE QUESTIONNAIRE . .4 2.4 METHODS OF DATA ANALYSIS . -

Diapositive 1

CLEANING-UP DEW LINE SITES IN NUNAVUT: THE INUIT PERSPECTIVE AT CAM-F Kailapi Alorut, Jean-Pierre Pelletier and Michel Pouliot CLEANING-UP DEW LINE SITES IN NUNAVUT: The Inuit Perspective at CAM-F (Kinguraq) • Location of Iglulik (Igloolik) • Presentation of Iglulik and Sanirajaq (Hall Beach) • Use of the Kinguraq area • CAM-F Cleanup Project Summary • Mobilization to the Site • On-Site Activities • Project Local Requirements • Regional Pressure • Inuit Content • Local Benefits Site Location and History Iglulik Sanirajak 900 km Yellowknife Iqaluit Kuujjuaq Iglulik (or Igloolik) • Igloolik means "there is an igloo here" • First Settlement: 4,000 years • Roman Catholic Mission and RCMP detachment in the 1930s • Over 1,500 people • Igloolik Isuma Productions Inc. • Artcirq Sanirajak (or Hall Beach)« • Sanirajak, means "one that is along the coast" • Created with the DEW Line Radar System • Hall Beach is NWS site • Population is approximately 600 people Site Location and History • CAM-F is one of the 13 DEW Line Radar Stations located within the Qikiqtaaluk Region of Nunavut • One of the 4 landlocked Stations (FOX-3, FOX-B and CAM- D are the other three) Location of Kingurak (Sarcpa Lake) Iglulik 100 km Sanirajak 85 km Kingurak Use of the Kingurak Area CAM-F Cleanup: Before and After Pictures: UMA/AECOM CLEANING-UP DEW LINE SITES IN NUNAVUT: The Inuit Perspective at CAM-F (Kinguraq) Mobilization: Sealift and CAT-Train Route 55 km 40 km 30 km Total CAT-Train Distance: Hall Beach – CAM-F: 125 km The Construction Camp Debris Collection Barrel -

Community Wellness Plan Arviat

Community Wellness Plan Arviat Prepared by: Arviat Community Wellness Working Group as Part of the Nunavut Community Wellness Project. Arviat Community Wellness Plan The Nunavut Community Wellness Project was a tripartite project led by Nunavut Tunngavik Inc. in partnership with Government of Nunavut, Department of Health and Social Services and Health Canada. Photographic images on cover, inside front cover, table of contents, headers and on pages 2, 11 and 12 taken by Kukik Tagalik. July, 2011 table of contents PAGE 2 1. Introduction 2 2. Community Wellness Working Group 3 2.1 Purpose of Working Group 3 2.2 Objectives of the Nunavut Community Wellness Working Groups 3 2.3 Description of the Group 4 3. Community Overview 4 4. Creating Awareness in the Community 4 4.1 Description of Community-Based Awareness Activities 5 5. What are the Resources in Our Community 5 5.1 Community Map and Description (From Assets Exercise) 5 5.2 Community Assets and Description (From Asset Exercise) 7 6. Issues Identification 7 6.1 Process for Identifying Issues 7 6.2 What are the Issues 7 7. Community Vision for Wellness 7 7.1 Process for Identifying Vision 7 7.2 Community Goals (Prioritized) 8 8. Community Plan 8 8.1 Connecting Assets to Wellness Vision (from Assets Exercise) 10 8.2 Steps to Reach Goals and Objectives 12 9. Conclusions 12 9.1 Establish a Community Wellness Working Group 12 9.2 The Hiring of the Pilot Coordinator 12 9.3 Development of a Community Wellness Planning Process 13 9.4 Presentation of Recommendations to the Hamlet Council 13 9.5 Ongoing Communication and Work 13 10. -

Sustainability in Iqaluit

2014-2019 Iqaluit Sustainable Community Plan Part one Overview www.sustainableiqaluit.com ©2014, The Municipal Corporation of the City of Iqaluit. All Rights Reserved. The preparation of this sustainable community plan was carried out with assistance from the Green Municipal Fund, a Fund financed by the Government of Canada and administered by the Federation of Canadian Municipalities. Notwithstanding this support, the views expressed are the personal views of the authors, and the Federation of Canadian Municipalities and the Government of Canada accept no responsibility for them. Table of Contents Acknowledgements INTRODUCTION to Part One of the Sustainable Community Plan .........................................................2 SECTION 1 - Sustainability in Iqaluit ....................................................................................................3 What is sustainability? .............................................................................................................................. 3 Why have a Sustainable Community Plan? .............................................................................................. 3 Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit and sustainability .............................................................................................. 4 SECTION 2 - Our Context ....................................................................................................................5 Iqaluit – then and now ............................................................................................................................. -

Community Wellness Plan Clyde River

Community Wellness Plan Clyde River Prepared by: Clyde River Community Wellness Working Group as Part of the Nunavut Community Wellness Project. Clyde River Community Wellness Plan The Nunavut Community Wellness Project was a tripartite project led by Nunavut Tunngavik Inc. in partnership with Government of Nunavut, Department of Health and Social Services and Health Canada. Community Wellness Planning Committee of Clyde River is happy to share photos of their land and community in this publication. Cover and inside cover photos: Robert Kautuk July, 2011 table of contents PAGE 2 1. Introduction 2 2. Community Wellness Working Group 3 2.1 Purpose of Working Group 3 2.2 Description of the Working Group 4 3. Community Overview (Population, Economy, Places and People of Interest) 5 4. Creating Awareness in the Community 5 4.1 Description of Community-Based Awareness Activities 6 5. What are the Resources in Our Community 6 5.1 Community Map and Description (From Assets Exercise) 7 Land and Wildlife 8 5.2 Community Assets and Description (From Asset Mapping Exercise) 14 6. Community Vision for Wellness 14 6.1 Process for Identifying Vision 15 7. Issues Identification 15 7.1 Process for Identifying Wellness Issues 17 7.2 What are the Wellness Issues 18 8. Community Plan 18 8.1 Connecting Assets to Wellness Vision 20 9. Signatories of Working Group 21 Appendix 1 22 Note Page 2 Community Wellness Plan | Clyde River 1. Introduction The Nunavut Community Wellness Project (NCWP) is a partnership between Nunavut Tunngavik Incorporated (NTI), the Government of Nunavut’s Department of Health and Social Services (HSS), and Health Canada’s Northern Region (HC). -

Peter Pitseolak and Zacharias Kunuk on Reclaiming Inuit Photographic Images and Imaging

Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society Vol. 3, No. 1, 2014, pp. 48-72 Control mapping: Peter Pitseolak and Zacharias Kunuk on reclaiming Inuit photographic images and imaging David Winfield Norman University of Oslo Abstract Inuit have been participating in the development of photo-reproductive media since at least the 19th century, and indeed much earlier if we continue on Michelle Raheja’s suggestion that there is much more behind Nanook’s smile than Robert Flaherty would have us believe. This paper examines how photographer Peter Pitseolak (1902-1973) and filmmaker Zacharias Kunuk have employed photography and film in relation to Raheja’s notion of “visual sovereignty” as a process of infiltrating media of representational control, altering their principles to visualize Indigenous ownership of their images. For camera-based media, this pertains as much to conceptions of time, continuity and “presence,” as to the broader dynamics of creative retellings. This paper will attempt to address such media-ontological shifts – in Pitseolak’s altered position as photographer and the effect this had on his images and the “presence” of his subjects, and in Kunuk’s staging of oral histories and, through the nature of film as an experience of “cinematic time,” composing time in a way that speaks to Inuit worldviews and life patterns – as radical renegotiations of the mediating properties of photography and film. In that they displace the Western camera’s hegemonic framing and time-based structures, repositioning Inuit “presence” and relations to land within the fundamental conditions of photo-reproduction, this paper will address these works from a position of decolonial media aesthetics, considering the effects of their works as opening up not only for more holistic, community-grounded representation models, but for expanding these relations to land and time directly into the expanded sensory field of media technologies. -

SEALIFT RATES for 2019 SEASON

514-597-0186 | 1-877-225-NEAS | FAX 514-523-7875 | www.NEAS.ca SEALIFT RATES for 2019 SEASON NUNAVUT as at April 1st, 2019 Port of Loading: VALLEYFIELD, Quebec, Canada DESTINATIONS NORTHBOUND NORTHBOUND 20' NSDR RETROGRADE RETROGRADE 20' RETROGRADE & EMPTY DRUMS & (rate per revenue ton) MERCHANT (NEAS Stuffed, Delivered, EMPTY 20' CONTAINER CYLINDERS LATERAL CARGO 20' CONTAINER Returned 20' container) PER UNIT PER UNIT (rate per revenue ton) Iqaluit "C" $274,62 $4 230,28 $6 663,28 $28,59 $612,54 $178,50 Iqaluit High Arctic "A" Arctic Bay Clyde River Grise Fjord Nanisivik $359,36 $5 535,53 $7 968,53 $28,59 $612,54 $233,58 Pond Inlet Qikiqtarjuaq Resolute Bay Foxe Basin "B" Hall Beach Igloolik $360,00 $5 545,44 $7 978,44 $28,59 $612,54 $234,00 Repulse Bay South Baffin "D" Cape Dorset Kimmirut $305,25 $4 702,06 $7 135,06 $28,59 $612,54 $198,41 Pangnirtung Kivalliq "E" Arviat Baker Lake $334,86 $5 158,11 $7 591,11 $28,59 $612,54 $217,66 Chesterfield Inlet Coral Harbour Rankin Inlet Kugaaruk "F" $416,53 $6 416,18 $8 849,18 $28,59 $612,54 $270,74 Kugaaruk Kitikmeot "G" Cambridge Bay Kugluktuk $446,00 $6 870,18 $9 303,18 $28,59 $612,54 $289,90 Gjoa Haven Taloyoak Sanikiluaq "H" $342,00 $5 268,19 $7 701,19 $28,59 $612,54 $222,30 Sanikiluaq NOTICE (1) Based on 20' container unit measuring 20'L x 8'W x 8.5'H; maximum unit weight 15 000 kg gross. -

Community Wellness Plan Igloolik

Community Wellness Plan Igloolik Prepared by: Igloolik Community Wellness Working Group as Part of the Nunavut Community Wellness Project. Igloolik Community Wellness Plan The Nunavut Community Wellness Project was a tripartite project led by Nunavut Tunngavik Inc. in partnership with Government of Nunavut, Department of Health and Social Services and Health Canada. Community Wellness Planning Committee of Igloolik is happy to share photos of their land and community in this publication. July, 2011 table of contents PAGE 2 1. Introduction 2 2. Community Wellness Working Group 3 2.1 Purpose of Working Group 3 2.2 Description of the Working Group 5 3. Community Overview 6 4. Creating Awareness in the Community 6 4.1 Description of Community-Based Awareness Activities 7 5. What are the Resources in Our Community 7 5.1 Community Map and Description (From Assets Exercise) 8 5.2 Community Assets and Description (From Asset Mapping Exercise) 8 6. Community Vision for Wellness 8 6.1 Process for Identifying Vision 9 7. Issues Identification 9 7.1 Process for Identifying Wellness Issues 11 7.2 What are the Wellness Issues 11 7.3 Community Goals (Prioritized) 11 8. Community Plan 11 8.1 Connecting Assets to Wellness Vision (from Assets Exercise) 11 8.2 Steps to Reach Goals and Objectives 11 9. Conclusions 12 10. Signatories of Working Group 13 Appendix I – Community Businesses, Organizations and Committees 16 Appendix II – Community Goals and Wellness Issues 19 Appendix III – Assets to Wellness Vision 20 Note Page 2 Community Wellness Plan | Igloolik 1. Introduction The Nunavut Community Wellness Project (NCWP) is a partnership between Nunavut Tunngavik Incorporated (NTI), the Government of Nunavut’s Department of Health and Social Services (HSS), and Health Canada’s Northern Region (HC). -

Igloolik 2013

Igloolik 2013 Igloolik is located on a small island in Foxe Basin, just off Melville Peninsula on the mainland of Nunavut. Although Igloolik is part of the Qikiqtani or Baffin region, there exists a mix of Inuit cultural traditions from each of the three regions. Igloolik is a community that balances modern living with a traditional way of life. This balance is illustrated by Isuma Production’s Atanarjuat, the award winning movie based on traditional legend. Getting There: First Air operates flights from Iqaluit to Igloolik on Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, Friday and Saturday with stops in Hall Beach. Canadian North operates flights from Iqaluit to Igloolik on Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, Friday, Saturday and Sunday, with stops in Hall Beach and Pond Inlet. Community Services and Information Population 1828 Region Qikiqtani Time Zone Eastern Postal Code X0A 0L0 Population based on 2012 Nunavut Bureau of Statistics population estimates (Area Code is 867 unless as indicated) RCMP General Inquiries 934-0123 Department of Recreation Emergency Only 934-1111 Office 934-8410 Health Centre 934-2100 Fire Emergency 934-8888 Local Communications Post Office 934-4188 Internet (Qiniq) 934-8909 Search & Rescue 934-8830 Cable 934-8958 Radio Society 934-8080 Schools/College Cell Phone Service Ataguttaaluk Elementary (K-6) 934-8996 Ataguttaaluk High (7-12) 934-8600 Airport 934-8947 Arctic College 934-8733 Hunters & Trappers Organization 934-8807 Early Childhood Services Preschool 934-8465 Qikiqtaani Inuit Association 934-8760 Churches Banks Roman Catholic Church 934-8846 Light banking services available at the Northern Anglican Church 934-8701 Store and Igloolik Co-op Store. -

Impact of 1, 2 and 4 °C of Global Warming on Ship Navigation in the Canadian Arctic

ARTICLES https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-021-01087-6 Impact of 1, 2 and 4 °C of global warming on ship navigation in the Canadian Arctic Lawrence R. Mudryk 1 ✉ , Jackie Dawson 2, Stephen E. L. Howell 1, Chris Derksen 1, Thomas A. Zagon 3 and Mike Brady 1 Climate change-driven reductions in sea ice have facilitated increased shipping traffic volumes across the Arctic. Here, we use climate model simulations to investigate changing navigability in the Canadian Arctic for major trade routes and coastal com- munity resupply under 1, 2 and 4 °C of global warming above pre-industrial levels, on the basis of operational Polar Code regu- lations. Profound shifts in ship-accessible season length are projected across the Canadian Arctic, with the largest increases in the Beaufort region (100–200 d at 2 °C to 200–300 d at 4 °C). Projections along the Northwest Passage and Arctic Bridge trade routes indicate 100% navigation probability for part of the year, regardless of vessel type, above 2 °C of global warming. Along some major trade routes, substantial increases to season length are possible if operators assume additional risk and operate under marginally unsafe conditions. Local changes in accessibility for maritime resupply depend strongly on commu- nity location. ver 90% of goods traded internationally are shipped by sea1, since 2015 and the adoption of the United Nations Framework which accounts for ~40% of the entire global economy2. Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) Paris Agreement, OMaritime trade (the movement of goods) and transporta- which binds signatory nations to a collective goal of keeping global tion (the movement of people) support every economic sector temperature increase to below 2 °C above pre-industrial levels, it has worldwide and play a substantial role in underpinning economic become increasingly important for studies to evaluate projections growth, improving social conditions, reducing risks to human on the basis of degrees warming instead of difficult-to-compare health and contributing to poverty alleviation3–5. -

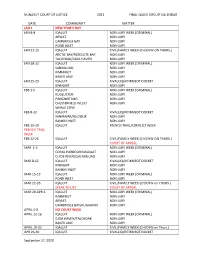

FINAL 2021 Quick Circuit Schedule.Pdf

NUNAVUT COURT OF JUSTICE 2021 FINAL QUICK CIRCUIT CALENDAR DATE COMMUNITY MATTER JAN 1 NEW YEAR’S DAY JAN 4-8 IQALUIT NON-JURY WEEK (CRIMINAL) ARVIAT NON-JURY CAMBRIDGE BAY NON-JURY POND INLET NON-JURY JAN 11-15 IQALUIT CIVIL/FAMILY WEEK (CH/CHW ON THURS.) ARCTIC BAY/RESOLUTE BAY NON-JURY TALOYOAK/GJOA HAVEN NON-JURY JAN 18-22 IQALUIT NON-JURY WEEK (CRIMINAL) SANIKILUAQ NON-JURY KIMMIRUT NON-JURY BAKER LAKE NON-JURY JAN 25-29 IQALUIT KIVALLIQ/KITIKMEOT DOCKET KINNGAIT NON-JURY FEB 1-5 IQALUIT NON-JURY WEEK (CRIMINAL) KUGLUKTUK NON-JURY PANGNIRTUNG NON-JURY CHESTERFIELD INLET/ NON-JURY WHALE COVE FEB 8-12 IQALUIT KIVALLIQ/KITIKMEOT DOCKET SANIRAJAK/IGLOOLIK NON-JURY RANKIN INLET NON-JURY FEB 15-19 IQALUIT FRENCH TRIAL/CONFLICT WEEK FRENCH TRIAL WEEK FEB 22-26 IQALUIT CIVIL/FAMILY WEEK (CH/CHW ON THURS.) COURT OF APPEAL MAR 1-5 IQALUIT NON-JURY WEEK (CRIMINAL) CORAL HARBOUR/NAUJAAT NON-JURY CLYDE RIVER/QIKITARJUAQ NON-JURY MAR 8-12 IQALUIT KIVALLIQ/KITIKMEOT DOCKET KINNGAIT NON-JURY RANKIN INLET NON-JURY MAR 15-19 IQALUIT NON-JURY WEEK (CRIMINAL) POND INLET NON-JURY MAR 22-26 IQALUIT CIVIL/FAMILY WEEK (CH/CHW on THURS.) SPEAK TO LIST COURT OF APPEAL MAR 29-APR 2 IQALUIT NON-JURY WEEK (CRIMINAL) KIMMIRUT NON-JURY ARVIAT NON-JURY CAMBRIDGE BAY/KUGAARUK NON-JURY APRIL 5-9 NO COURT WEEK APRIL 12-16 IQALUIT NON-JURY WEEK (CRIMINAL) GJOA HAVEN/TALOYOAK NON-JURY BAKER LAKE NON-JURY APRIL 19-23 IQALUIT CIVIL/FAMILY WEEK (CH/CHW on Thurs.) APR 26-30 IQALUIT KIVALLIQ/KITIKMEOT DOCKET September 17, 2020 NUNAVUT COURT OF JUSTICE 2021 FINAL QUICK CIRCUIT CALENDAR DATE COMMUNITY MATTER MAY 3-7 IQALUIT NON-JURY WEEK (CRIMINAL) PANGNIRTUNG NON-JURY RANKIN INLET NON-JURY MAY 10-14 IQALUIT CIVIL/FAMILY WEEK (CH/CHW on Thurs.) COURT OF APPEAL KUGLUKTUK NON-JURY SANIKILUAQ NON-JURY MAY 17-21 IQALUIT NON-JURY WEEK (CRIMINAL) FRENCH TRIAL KINNGAIT NON-JURY WEEK MAY 24-28 IQALUIT KIVALLIQ/KITIKMEOT DOCKET MAY 24 – VICTORIA DAY MAY 31-JUNE 4 IQALUIT NON-JURY WEEK (CRIMINAL) WHALE COVE/CHESTERFIELD IN. -

TAB3A GN BN GB Polar Bear TAH

SUBMISSION TO THE NUNAVUT WILDLIFE MANAGEMENT BOARD FOR Information: Decision: X Issue: Total Allowable Harvest Recommendations for the Gulf of Boothia Polar Bear Subpopulation Background: • The Gulf of Boothia (GB) polar bear subpopulation is entirely managed by Nunavut (Figure 1). The last inventory study to estimate abundance was conducted between 1998-2000, which resulted in an estimate of 1592 bears. The GB polar bear subpopulation was considered stable in 2000, or slightly increasing. • Communities from Igloolik, Sanirajak, Naujaat, Taloyoak, Gjoa Haven, and Kugaaruk harvest from GB. The current Total Allowable Harvest (TAH) for GB is 74 bears per year. The average harvest between 2004/2005 and 2018/2019 was 63 bears per year (Figure 2). The lower actual harvest relative to the TAH is likely a result of proactive management by communities, whereby they stopped the harvest when the female allocation in the 2:1 male to female quota was reached to avoid female overharvest and subsequent quota reductions, and poor ice conditions that prevented travel to preferred GB hunting locations. • The population data were out-of-date, and a new study was needed to assess the status of this subpopulation. Following community consultations during 2012 and 2013, a new 3-year study began in 2015. The method used for this study was the less-invasive genetic mark-recapture DNA-biopsy sampling. The new study was conducted between 2015 and 2017. • The Government of Nunavut, Department of Environment (DOE) initially planned to have a community project to collect local traditional knowledge from GB community members and hunters. However, the COVID-19 pandemic prevented local in-person meetings for interviews during 2020.