Studying the Hotspot of Costa Rica and Panama

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Physiology / Fisiología

Botanical Sciences 98(4): 524-533. 2020 Received: January 08, 2019, Accepted: June 10, 2020 DOI: 10.17129/botsci.2559 On line first: October 12, 2020 Physiology / Fisiología ASYMBIOTIC GERMINATION, EFFECT OF PLANT GROWTH REGULATORS, AND CHITOSAN ON THE MASS PROPAGATION OF STANHOPEA HERNANDEZII (ORCHIDACEAE) GERMINACIÓN ASIMBIÓTICA, EFECTO DE LOS REGULADORES DE CRECIMIENTO VEGETAL Y EL QUITOSANO EN LA PROPAGACIÓN MASIVA DE STANHOPEA HERNANDEZII (ORCHIDACEAE) ID JESÚS ARELLANO-GARCÍA1, ID OSWALDO ENCISO-DÍAZ2, ID ALEJANDRO FLORES-PALACIOS3, ID SUSANA VALENCIA-DÍAZ1, ID ALEJANDRO FLORES-MORALES4, ID IRENE PEREA-ARANGO1* 1Centro de Investigación en Biotecnología, Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Morelos, Cuernavaca. Morelos, Mexico. 2Facultad de Ciencias Biológicas y Agropecuarias, Campus Tuxpan, Universidad Veracruzana, Veracruz, Mexico. 3Centro de Investigación en Biodiversidad y Conservación, Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Morelos, Cuernavaca, Morelos, Mexico. 4Facultad de Ciencias Biológicas, Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Morelos, Cuernavaca, Morelos, Mexico. *Author for correspondence: [email protected] Abstract Background: Stanhopea hernandezii was collected from natural habitat in Mexico for its beautiful fragrant flowers. Biotechnological strategies of propagation may satisfy the market demand and are useful for conservation programs. Hypothesis: Vigorous seedlings of S. hernandezii can be produced in vitro by asymbiotic seed germination techniques and the addition of chitosan to the culture medium in the temporary immersion system (RITA®) and in semi-solid medium systems. Methods: The first step was the in vitro germination of seeds obtained from a mature capsule of wild plants, followed by multiplication via adventitious protocorm induction known as protocorm-like bodies, using plant growth regulators. For this purpose, we utilized Murashige and Skoog (MS) basal medium amended with 0.5 mg/L α-Naphthaleneacetic acid, combined with different concentrations of 6- Benzylaminepurine (1, 3, and 5 mg/L). -

An Asian Orchid, Eulophia Graminea (Orchidaceae: Cymbidieae), Naturalizes in Florida

LANKESTERIANA 8(1): 5-14. 2008. AN ASIAN ORCHID, EULOPHIA GRAMINEA (ORCHIDACEAE: CYMBIDIEAE), NATURALIZES IN FLORIDA ROBE R T W. PEMBE R TON 1,3, TIMOTHY M. COLLINS 2 & SUZANNE KO P TU R 2 1Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden, 2121 SW 28th Terrace Ft. Lauderdale, Florida 33312 2Department of Biological Sciences, Florida International University, Miami, FL 33199 3Author for correspondence: [email protected] ABST R A C T . Eulophia graminea, a terrestrial orchid native to Asia, has naturalized in southern Florida. Orchids naturalize less often than other flowering plants or ferns, butE. graminea has also recently become naturalized in Australia. Plants were found growing in five neighborhoods in Miami-Dade County, spanning 35 km from the most northern to the most southern site, and growing only in woodchip mulch at four of the sites. Plants at four sites bore flowers, and fruit were observed at two sites. Hand pollination treatments determined that the flowers are self compatible but fewer fruit were set in selfed flowers (4/10) than in out-crossed flowers (10/10). No fruit set occurred in plants isolated from pollinators, indicating that E. graminea is not autogamous. Pollinia removal was not detected at one site, but was 24.3 % at the other site evaluated for reproductive success. A total of 26 and 92 fruit were found at these two sites, where an average of 6.5 and 3.4 fruit were produced per plant. These fruits ripened and dehisced rapidly; some dehiscing while their inflorescences still bore open flowers. Fruit set averaged 9.2 and 4.5 % at the two sites. -

Network Scan Data

Selbyana 29(1): 69-86. 2008. THE ORCHID POLLINARIA COLLECTION AT LANKESTER BOTANICAL GARDEN, UNIVERSITY OF COSTA RICA FRANCO PUPULIN* Lankester Botanical Garden, University of Costa Rica. P.O. Box 1031-7050 Cartago, Costa Rica, CA Angel Andreetta Research Center on Andean Orchids, University Alfredo Perez Guerrero, Extension Gualaceo, Ecuador Harvard University Herbaria, Cambridge, MA, USA The Marie Selby Botanical Gardens, Sarasota, FL, USA Email: [email protected] ADAM KARREMANS Lankester Botanical Garden, University of Costa Rica. P.O. Box 1031-7050 Cartago, Costa Rica, CA Angel Andreetta Research Center on Andean Orchids, University Alfredo Perez Guerrero, Extension Gualaceo, Ecuador ABSTRACT. The relevance of pollinaria study in orchid systematics and reproductive biology is summa rized. The Orchid Pollinaria Collection and the associate database of Lankester Botanical Garden, University of Costa Rica, are presented. The collection includes 496 pollinaria, belonging to 312 species in 94 genera, with particular emphasis on Neotropical taxa of the tribe Cymbidieae (Epidendroideae). The associated database includes digital images of the pollinaria and is progressively made available to the general public through EPIDENDRA, the online taxonomic and nomenclatural database of Lankester Botanical Garden. Examples are given of the use of the pollinaria collection by researchers of the Center in a broad range of systematic applications. Key words: Orchid pollinaria, systematic botany, pollination biology, orchid pollinaria collection, -

Micropropagation of Cattleya Maxima J. Lindley in Culture Medium with Banana Flour and Coconut Water

Int J Plant Anim Environ Sci 2020; 10 (4): 179-193 Research Article Micropropagation of Cattleya maxima J. Lindley in Culture Medium with Banana Flour and Coconut Water Joe A Vilcherrez-Atoche1, Consuelo Rojas-Idrogo2,3, Guillermo E Delgado-Paredes2,3* 1Laboratório de Fisiología Vegetal e Cultura de Tecidos do Centro de Ciências Agrárias da UFSCar, Araras, SP, Brazil 2Laboratorio de Cultivo de Tejidos Vegetales y Recursos Genéticos, Facultad de Ciencias Biológicas, Universidad Nacional Pedro Ruiz Gallo, Juan XXIII 391, Ciudad Universitaria, Lambayeque, Perú 3Laboratorio General de Biotecnología, Vicerrectorado de Investigación (UNPRG), Atahualpa 423, Lambayeque, Perú *Corresponding Author: Guillermo E Delgado-Paredes, Laboratorio General de Biotecnología, Vicerrectorado de Investigación (UNPRG), Atahualpa 423, Lambayeque, Perú, Tel: +51 948301087; E- mail: [email protected] Received: 01 December 2020; Accepted: 14 December 2020; Published: 18 December 2020 Citation: Joe A Vilcherrez-Atoche, Consuelo Rojas-Idrogo, Guillermo E Delgado-Paredes. Micropropagation of Cattleya maxima J. Lindley in Culture Medium with Banana Flour and Coconut Water. International Journal of Plant, Animal and Environmental Sciences 10 (2020): 179-193. Abstract Cattleya maxima J. Lindley is one species of the large- with the culture of viable seeds by hypodermic syringe flowered, epiphyte and o c casional lithophyte of the method. Viability, seeds germination, the morphogenic Orchidaceae family, seriously threatened by processes of induction and multiplication of protocorm- indiscriminate extraction and destruction of their natural like bodies (PLBs), elongation and differentiation of habitat, climate change and pollution. Therefore, the seedlings were determined. The Murashige and Skoog aim of the present study was to establish a reproducible (MS) medium supplemented with two complex organic in vitro propagation and mass multiplication protocol substances, coconut water and banana flour, was used, for germplasm conservation of this species in natural as well as the NAA-BAP treatment. -

Crassulacean Acid Metabolism in Tropical Orchids: Integrating Phylogenetic, Ecophysiological and Molecular Genetic Approaches

University of Nevada, Reno Crassulacean acid metabolism in tropical orchids: integrating phylogenetic, ecophysiological and molecular genetic approaches A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Biochemistry and Molecular Biology by Katia I. Silvera Dr. John C. Cushman/ Dissertation Advisor May 2010 THE GRADUATE SCHOOL We recommend that the dissertation prepared under our supervision by KATIA I. SILVERA entitled Crassulacean Acid Metabolism In Tropical Orchids: Integrating Phylogenetic, Ecophysiological And Molecular Genetic Approaches be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY John C. Cushman, Ph.D., Advisor Jeffrey F. Harper, Ph.D., Committee Member Robert S. Nowak, Ph.D., Committee Member David K.Shintani, Ph.D., Committee Member David W. Zeh, Ph.D., Graduate School Representative Marsha H. Read, Ph. D., Associate Dean, Graduate School May, 2010 i ABSTRACT Crassulacean Acid Metabolism (CAM) is a water-conserving mode of photosynthesis present in approximately 7% of vascular plant species worldwide. CAM photosynthesis minimizes water loss by limiting CO2 uptake from the atmosphere at night, improving the ability to acquire carbon in water and CO2-limited environments. In neotropical orchids, the CAM pathway can be found in up to 50% of species. To better understand the role of CAM in species radiations and the molecular mechanisms of CAM evolution in orchids, we performed carbon stable isotopic composition of leaf samples from 1,102 species native to Panama and Costa Rica, and character state reconstruction and phylogenetic trait analysis of CAM and epiphytism. When ancestral state reconstruction of CAM is overlain onto a phylogeny of orchids, the distribution of photosynthetic pathways shows that C3 photosynthesis is the ancestral state and that CAM has evolved independently several times within the Orchidaceae. -

Orchid Research Newsletter 73 (PDF)

Orchid Research Newsletter No. 73 January 2019 Hermann Sleumer (1906–1993), the eminent German botanist who worked for many years at the Rijksherbarium in Leiden, sometimes told an anecdote about Rudolf Schlechter (1872–1925), whom he had witnessed as a young student in Berlin about 1925. Schlechter, the foremost orchid taxonomist of his time, was by then seriously ill with malaria, which he had probably caught during his expeditions in New Guinea almost two decades earlier. To alleviate the symptoms, Schlechter had taken to drinking large quantities of beer, and, according to Sleumer, he would sometimes complain, "It's already noon and I haven't done anything for eternity yet [Schon zwölf Uhr und noch nichts für die Ewigkeit getan]." This meant that he had not yet described a new species that day and that he was getting too inebriated to do so after lunch time. Sadly, the malaria killed him soon afterwards. Schlechter didn't live long enough to witness how the herbarium of the Botanical Museum in Berlin went up in flames in March 1943 after a bombing raid, destroying his first set of collections and his archives. Sleumer used to tell how he found his own typewriter half molten in the rubble afterwards. On a lighter note, he once told Jaap Vermeulen (pers. comm.) that Schlechter had a very pretty daughter whom he wished he had married. But enough Leiden folklore—I wanted to draw attention to Schlechter's attitude towards describing new species. It sounds like an almost pompous thing to say: doing something for eternity. -

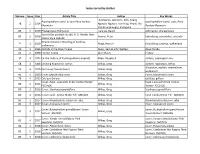

Sorted by Author

Index sorted by Author Volume Issue Year Article Title Author Key Words Averyanov, Leonid V., Sinh, Khang Paphiopedilum canhii in Laos Phou Pachao paphiopedilum canhii, Laos, Phou 78 2 2014 Nguyen, Nguyen, Tien Hiep, Pham, The Mountain Pachao Mountain Van & Lorphengsy, Shengvilai 83 4 2019 Phalaenopsis Pollination Lafarge, David pollination, phalaenopsis Sarcochilus australis (Lindl.) H. G. Reichb. Non- 82 3 2018 Adams, Peter hybridizing, sarcochilus, australis Classic Style Hybrids New Directions in Breeding of Cattleya 74 1 2010 Akagi, Harry Y. hybridizing, cattleya, walkeriana walkeriana 30 1 1966 Orchids in the Rose Parade Akers, Sam & John Walters Rose Parade 62 2 1998 Forever Young Alan Moon history 37 4 1973 On the Culture of Paphiopedilums (reprint) Allen, Douglas R. culture, paphiopedilums 68 4 2004 Growing Rupicolous Laelias Allikas, Greg culture, rupicolous, laelias discussion, section, dendrobium, 74 4 2010 Pedilonum Dendrobiums Allikas, Greg pedilonum 84 3 2020 Cover: Masdevallia rosea Allikas, Greg cover, Masdevallia rosea 79 4 2015 Cattleya Gallery Allikas, Greg cattleya, gallery Cover: Paph . Leonard’s Pride ‘Jordon Winter’ Paph. Leonard’s Pride ‘Jordon 80 3 2016 Allikas, Greg FCC/AOS Winter’ FCC/AOS 80 3 2016 Cover: Stanhopea grandiflora Allikas, Greg Stanhopea grandiflora 80 4 2016 Cover: Cycd . Jumbo Micky ‘Fifi ’ AM/AOS Allikas, Greg Cycd. Jumbo Micky ‘Fifi ’ AM/AOS 81 1 2017 Cover: Rhynchostylis retusa var. alba. Allikas, Greg Rhynchostylis retusa var. alba 81 3 2017 Cover: Angraecum leonis Allikas, Greg cover, Angraecum -

Anatomía Foliar Comparada Y Relaciones Filogenéticas De 11 Especies De Laeliinae Con Énfasis En Brassavola (Orchidaceae)

Anatomía foliar comparada y relaciones filogenéticas de 11 especies de Laeliinae con énfasis en Brassavola (Orchidaceae) Eliana Noguera-Savelli1 & Damelis Jáuregui2 1. Posgrado en Ciencias Biológicas, Unidad de Recursos Naturales, Centro de Investigación Científica de Yucatán, A.C. (CICY), Colonia Chuburná de Hidalgo, Calle 43. N°130. Mérida, Yucatán, México C.P. 97200; [email protected] 2. Universidad Central de Venezuela, Facultad de Agronomía, Instituto de Botánica Agrícola, Laboratorio de Morfoanatomía Vegetal, Prolongación Av. 19 de abril, Maracay 2101, Estado Aragua, Venezuela; [email protected] Recibido 05-I-2011. Corregido 25-I-2011. Aceptado 14-II-2011. Abstract: Comparative leaf anatomy and phylogenetic relationships of 11 species of Laeliinae with emphasis on Brassavola (Orchidaceae). Brassavola inhabits a wide altitude range and habitat types from Northern Mexico to Northern Argentina. Classification schemes in plants have normally used vegetative and floral characters, but when species are very similar, as in this genus, conflicts arise in species delimitation, and alternative methods should be applied. In this study we explored the taxonomic and phylogenetic value of the anatomical structure of leaves in Brassavola; as ingroup, seven species of Brassavola were considered, and as an outgroup Guarianthe skinneri, Laelia anceps, Rhyncholaelia digbyana and Rhyncholaelia glauca were evaluated. Leaf anatomical characters were studied in freehand cross sections of the middle portion with a light microscope. Ten vegetative anatomical characters were selected and coded for the phylogenetic analysis. Phylogenetic reconstruction was carried out under maximum parsimony using the program NONA through WinClada. Overall, Brassavola species reveal a wide variety of anatomical characters, many of them associated with xeromorphic plants: thick cuticle, hypodermis and cells of the mesophyll with spiral thickenings in the secondary wall. -

Orchids of Mexico There Are About 30,000 Orchids in the World

Orchids of Mexico There are about 30,000 orchids in the world. Over 1,200 of them can be found in Mexico. Of these, about 250 are found ONLY in Mexico. Many of the orchids shown here are common, however, some are rare, many are threatened and a few are endangered. At least one is extinct in the wild. Acineta barkeri Found in Oaxaca and Chiapas in cloud forests at elevations around 1000 to 2000 meters as a medium sized, warm growing epiphyte with ovoid, slightly compressed, longitudinally sulcate pseudobulbs partially enveloped by fibrous sheaths and carrying 3 to 4, apical, erect, plicate, coriaceous, elliptic, acuminate, attenuate and channeled below into the base leaves that blooms in the summer on basal, 2 to 3, pendant, terete, racemose, slightly flexuous, 12 to 16" (30 to 40 cm) long, 15 to 20 flowered inflorescence arising on a mature pseudobulb as a new growth appears, with several, tubular, scarious, coffee brown bracts and elliptic-ovate, cucullate, round to obtuse floral bracts carrying simultaneously opening, fragrant flowers. Acianthera breviflora Found in Oaxaca, a miniature sized epiphytic orchid. Very little data is available on this apparently rare orchid. Acianthera chrysantha Found in Jalisco, Michoacan, Guerrero, Mexico and Oaxaca on Pacific facing slopes or in humid sub-deciduous forests at elevations of 1500 to 2400 meters as a small sized, warm to cool growing epiphyte with a stiff, erect ramicaul carrying a single, apical, thick, rigid, sessile, oblong, obtuse apically and below into the elongate, channeled, petiolate base leaf that blooms on a apical, short, stiff, erect, fasciculate, (1" (2.5 cm) long, few (4 to 5) flowered inflorescence arising through a narrow spathe that holds the flowers close to the base of the leaf. -

STUDYING the HOTSPOT of COSTA RICA and PANAMA Lankesteriana International Journal on Orchidology, Vol

Lankesteriana International Journal on Orchidology ISSN: 1409-3871 [email protected] Universidad de Costa Rica Costa Rica Bogarín, Diego; Pupulin, Franco; Arrocha, Clotilde; Warner, Jorge ORCHIDS WITHOUT BORDERS: STUDYING THE HOTSPOT OF COSTA RICA AND PANAMA Lankesteriana International Journal on Orchidology, vol. 13, núm. 1-2, agosto, 2013, pp. 13-26 Universidad de Costa Rica Cartago, Costa Rica Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=44340043002 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative LANKESTERIANA 13(1–2): 13—26. 2013 ORCHIDS WITHOUT BORDERS: STUDYING THE HOTSPOT OF COSTA RICA AND PANAMA DIEGO BOGARÍN1,2,3, FRANCO PUPULIN1,3,4, CLOTILDE ARROCHA2 & JORGE WARNER1 1Jardín Botánico Lankester, Universidad de Costa Rica. P.O. Box 302-7050 Cartago, Costa Rica, A.C. 2Herbario UCH, Universidad Autónoma de Chiriquí, 0427, David, Chiriquí, Panama 3Centro de Investigación en Orquídeas de los Andes “Ángel Andreetta”, Universidad Alfredo Pérez Guerrero, Ecuador. 4Harvard University Herbaria, 22 Divinity Avenue, Cambridge, Massachusetts, U.S.A. and Marie Selby Botanical Gardens, Sarasota, FL, U.S.A. ABSTRACT. The Mesoamerican region is one of the richest in orchid diversity in the world. About 2670 species, 10% of all orchids known have been recorded there. Within this region, most of the species are concentrated in the southernmost countries. Costa Rica with 1598 species (or 0.030 spp/km2) and Panama with 1397 species (0.018 spp/km2) stand at the top of endemic species list of all Mesoamerica, with 35.37% and 28.52%, respectively. -

Cattleya” Skinneri Complex

LANKESTERIANA 7: 37-38. 2003. GUARIANTHE, A GENERIC NAME FOR THE “CATTLEYA” SKINNERI COMPLEX 1 2 ROBERT L. DRESSLER & WESLEY E. HIGGINS 1Missouri Botanical Garden; Florida Museum of Natural History; Marie Selby Botanical Gardens Mailing address: 21305 NW 86th Ave., Micanopy, Florida 32667, U.S.A. [email protected] 2Marie Selby Botanical Gardens, 811 South Palm Avenue, Sarasota, FL 34236-7726, U.S.A. [email protected] Molecular systematics, the comparison of DNA Though Cattleya bowringiana is not placed within sequences, has brought a continuing revolution to the C. skinneri alliance in the molecular analysis, plant taxonomy. In most cases, the results are intu- there is also no bootstrap support to exclude it from itively reasonable, even when they demand changing the clade. We treat C. bowringiana as a member of long-known names. The analysis of the Laeliinae, by Guarianthe because of the strong agreement in all van den Berg et al. (2000) has confirmed some clear structural features. Further analysis may falsify this relationships, showing, for example, that conclusion, but, in the meantime, we may call C. Schomburgkia is quite distinct from Myrmecophila bowringiana a Guarianthe. but very close to Laelia anceps. Among other things, There is a special problem involving the hybrid this study has shown that Cattleya, as we have known swarm between C. aurantiaca and C. skinneri. Plants it, is not clearly delimited. One of the clearest segre- from this hybrid swarm have been described as new, gates is the largely Central American "Cattleya" skin- including Cattleya deckeri Klotzsch, C. guatemalen- neri complex (van den Berg 2000).