Counting Topological Manifolds

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cantor Groups

Integre Technical Publishing Co., Inc. College Mathematics Journal 42:1 November 11, 2010 10:58 a.m. classroom.tex page 60 Cantor Groups Ben Mathes ([email protected]), Colby College, Waterville ME 04901; Chris Dow ([email protected]), University of Chicago, Chicago IL 60637; and Leo Livshits ([email protected]), Colby College, Waterville ME 04901 The Cantor set C is simultaneously small and large. Its cardinality is the same as the cardinality of all real numbers, and every element of C is a limit of other elements of C (it is perfect), but C is nowhere dense and it is a nullset. Being nowhere dense is a kind of topological smallness, meaning that there is no interval in which the set is dense, or equivalently, that its complement is a dense open subset of [0, 1]. Being a nullset is a measure theoretic concept of smallness, meaning that, for every >0, it is possible to cover the set with a sequence of intervals In whose lengths add to a sum less than . It is possible to tweak the construction of C that results in a set H that remains per- fect (and consequently has the cardinality of the continuum), is still nowhere dense, but the measure can be made to attain any number α in the interval [0, 1). The con- struction is a special case of Hewitt and Stromberg’s Cantor-like set [1,p.70],which goes like this: let E0 denote [0, 1],letE1 denote what is left after deleting an open interval from the center of E0.IfEn−1 has been constructed, obtain En by deleting open intervals of the same length from the center of each of the disjoint closed inter- vals that comprise En−1. -

1. Definition. Let I Be the Unit Interval. If I, G Are Maps on I Then 1 and G Are Conjugate Iff There Is a Homeomorphism H of I Such That 1 = H -I Gh

TRANSACTIONS OF THE AMERICAN MATHEMATICAL SOCIETY Volume 319. Number I. May 1990 A COMPLETE CLASSIFICATION OF THE PIECEWISE MONOTONE FUNCTIONS ON THE INTERVAL STEWART BALDWIN ABSTRACT. We define two functions f and g on the unit interval [0, I] to be strongly conjugate iff there is an order-preserving homeomorphism h of [0, I] such that g = h-1 fh (a minor variation of the more common term "conjugate", in which h need not be order-preserving). We provide a complete set of invariants for each continuous (strictly) piecewise monotone function such that two such functions have the same invariants if and only if they are strongly conjugate, thus providing a complete classification of all such strong conjugacy classes. In addition, we provide a criterion which decides whether or not a potential invariant is actually realized by some 'piecewise monotone continuous function. INTRODUCTION 1. Definition. Let I be the unit interval. If I, g are maps on I then 1 and g are conjugate iff there is a homeomorphism h of I such that 1 = h -I gh. A more convenient term for our purposes will be: I, g are strongly conjugate (written 1 ~ g) iff there is an order preserving homeomorphism h as above. Given a map 1 on I, define the map j by I*(x) = 1 - 1(1 - x) (essentially a 1800 rotation of the graph). The main result of this paper will be to give a complete set of invariants for the strong conjugacy classes of the piecewise monotone continuous functions on the unit interval I = [0, I]. -

Semisimplicial Unital Groups

International Journal of Theoretical Physics, Vol. 43, Nos. 7/8, August 2004 (C 2004) Semisimplicial Unital Groups David J. Foulis1 and Richard J. Greechie2 If there is an order-preserving group isomorphism from a directed abelian group G with a finitely generated positive cone G+ onto a simplicial group, then G is called a semisimplicial group. By factoring out the torsion subgroup of a unital group having a finite unit interval, one obtains a semisimplicial unital group. We exhibit a represen- tation for the base-normed space associated with a semisimplicial unital group G as the Banach dual space of a finite dimensional order-unit space that contains G as an additive subgroup. In terms of this representation, we formulate necessary and sufficient conditions for G to be archimedean. KEY WORDS: partially ordered abelian group; directed group; unital group; sim- plicial group; semisimplicial unital group; effect algebra; state; base-normed space, order-unit space. 1. INTRODUCTION If H is a Hilbert space, then the set G of all bounded self-adjoint operators on H is organized in the usual way into a partially ordered real linear space (in fact, an order-unit Banach space), and the operators belonging to the interval E :={A ∈ G | 0 ≤ A ≤ 1} are called the effect operators on H. The set E, organized into a partial algebra under the restriction ⊕ of addition on G to E, is called the algebra of effect operators on H. In the contemporary theory of quantum measurement (Busch et al., 1991), an observable is represented by a positive-operator-valued (POV) measure defined on a σ-field of sets and taking on values in the effect algebra E. -

Chapter 1: Interval Analysis, Fuzzy Set Theory and Possibility Theory In

Draft 1.0 November 4, 2010 CHAPTER 1 of the book Lodwick, Weldon A. (2011). Flexible and Un- certainty Optimization (to be published) Interval Analysis, Fuzzy Set Theory and Possibility Theory in Optimization Weldon A. Lodwick University of Colorado Denver Department of Mathematical and Statistical Sciences, Campus Box 170 P.O. Box 173364 Denver, CO 80217-3364, U.S.A. Email: [email protected] Abstract: This study explores the interconnections between interval analysis, fuzzy interval analysis, and interval, fuzzy, and possibility optimization. The key ideas considered are: (1) Fuzzy and possibility optimization are impor- tant methods in applied optimization problems, (2) Fuzzy sets and possibility distributions are distinct which in the context of optimization lead to ‡exible optimization on one hand and optimization under uncertainty on the other, (3) There are two ways to view possibility analysis leading to two distinct types of possibility optimization under uncertainty, single and dual distribu- tion optimization, and (4) The semantic (meaning) of constraint set in the presence of fuzziness and possibility needs to be known a-priori in order to determine what the constraint set is and how to compute its elements. The thesis of this exposition is that optimization problems that intend to model real problems are very (most) often satis…cing and epistemic and that the math- ematical language of fuzzy sets and possibility theory are well-suited theories for stating and solving a wide classes of optimization problems. Keywords: Fuzzy optimization, possibility optimization, interval analysis, constraint fuzzy interval arithmetic 1 Introduction This exposition explores interval analysis, fuzzy interval analysis, fuzzy set theory, and possibility theory as they relate to optimization which is both a synthesis of the author’s previous work bringing together, transforming, 1 and updating many ideas found in [49],[50], [51], [52], [58], [63], [64], [118], [116], and [117] as well as some new material dealing with the computation of constraint sets. -

WHY a DEDEKIND CUT DOES NOT PRODUCE IRRATIONAL NUMBERS And, Open Intervals Are Not Sets

WHY A DEDEKIND CUT DOES NOT PRODUCE IRRATIONAL NUMBERS And, Open Intervals are not Sets Pravin K. Johri The theory of mathematics claims that the set of real numbers is uncountable while the set of rational numbers is countable. Almost all real numbers are supposed to be irrational but there are few examples of irrational numbers relative to the rational numbers. The reality does not match the theory. Real numbers satisfy the field axioms but the simple arithmetic in these axioms can only result in rational numbers. The Dedekind cut is one of the ways mathematics rationalizes the existence of irrational numbers. Excerpts from the Wikipedia page “Dedekind cut” A Dedekind cut is а method of construction of the real numbers. It is a partition of the rational numbers into two non-empty sets A and B, such that all elements of A are less than all elements of B, and A contains no greatest element. If B has a smallest element among the rationals, the cut corresponds to that rational. Otherwise, that cut defines a unique irrational number which, loosely speaking, fills the "gap" between A and B. The countable partitions of the rational numbers cannot result in uncountable irrational numbers. Moreover, a known irrational number, or any real number for that matter, defines a Dedekind cut but it is not possible to go in the other direction and create a Dedekind cut which then produces an unknown irrational number. 1 Irrational Numbers There is an endless sequence of finite natural numbers 1, 2, 3 … based on the Peano axiom that if n is a natural number then so is n+1. -

Topological Properties

CHAPTER 4 Topological properties 1. Connectedness • Definitions and examples • Basic properties • Connected components • Connected versus path connected, again 2. Compactness • Definition and first examples • Topological properties of compact spaces • Compactness of products, and compactness in Rn • Compactness and continuous functions • Embeddings of compact manifolds • Sequential compactness • More about the metric case 3. Local compactness and the one-point compactification • Local compactness • The one-point compactification 4. More exercises 63 64 4. TOPOLOGICAL PROPERTIES 1. Connectedness 1.1. Definitions and examples. Definition 4.1. We say that a topological space (X, T ) is connected if X cannot be written as the union of two disjoint non-empty opens U, V ⊂ X. We say that a topological space (X, T ) is path connected if for any x, y ∈ X, there exists a path γ connecting x and y, i.e. a continuous map γ : [0, 1] → X such that γ(0) = x, γ(1) = y. Given (X, T ), we say that a subset A ⊂ X is connected (or path connected) if A, together with the induced topology, is connected (path connected). As we shall soon see, path connectedness implies connectedness. This is good news since, unlike connectedness, path connectedness can be checked more directly (see the examples below). Example 4.2. (1) X = {0, 1} with the discrete topology is not connected. Indeed, U = {0}, V = {1} are disjoint non-empty opens (in X) whose union is X. (2) Similarly, X = [0, 1) ∪ [2, 3] is not connected (take U = [0, 1), V = [2, 3]). More generally, if X ⊂ R is connected, then X must be an interval. -

Interval Analysis and Constructive Mathematics

16w5099—INTERVAL ANALYSIS AND CONSTRUCTIVE MATHEMATICS Douglas Bridges (University of Canterbury), Hannes Diener (University of Canterbury), Baker Kearfott (University of Louisiana at Lafayette), Vladik Kreinovich (University of Texas at El Paso), Patricia Melin (Tijuana Institute of Technology), Raazesh Sainudiin (University of Canterbury), Helmut Schwichtenberg (University of Munich) 13–18 November 2016 1 Overview of the Field 1.1 Constructive Mathematics In this case, we have two fields to overview—constructive mathematics and interval analysis—one of the main objectives of the workshop being to foster joint research across the two. By ‘constructive mathematics’ we mean ‘mathematics using intuitionistic logic and an appropriate set or typetheoretic foundation’. Although the origins of the field go back to Brouwer, over 100 years ago, it was the publication, in 1967, of Errett Bishop’s Foundations of Constructive Analysis [16, 17] that began the modern revival of the field. Bishop adopted the highlevel viewpoint of the working mathematical analyst (he was already famous for his work in classical functional analysis and several complex variables), and devel oped constructively analysis across a wide swathe of the discipline: real, complex, and functional analysis, as well as abstract integration/measure theory. The significant aspect of his work is that the exclusive use of intuitionistic logic guaranteed that each proof embodied algorithms that could be extracted, encoded, and machineimplemented. For a rather simple example, Bishop’s proof of the fundamental theorem of algebra is, in effect, an algorithm enabling one to find the roots of a given complex polynomial; contrast this with the standard undergraduate proofs, such as the reductio ad absurdum one using Liouville’s theorem. -

An Intuitive Introduction to Motivic Homotopy Theory Vladimir Voevodsky

What follows is Vladimir Voevodsky's snapshot of his Fields Medal work on motivic homotopy, plus a little philosophy and \from my point of view the main fun of doing mathematics" Voevodsky (2002). Voevodsky uses extremely simple leading ideas to extend topological methods of homotopy into number theory and abstract algebra. The talk takes the simple ideas right up to the edge of some extremely refined applications. The talk is on-line as streaming video at claymath.org/video/. In a nutshell: classical homotopy studies a topological space M by looking at maps to M from the unit interval on the real line: [0; 1] = fx 2 R j 0 ≤ x ≤ 1 g as well as maps to M from the unit square [0; 1]×[0; 1], the unit cube [0; 1]3, and so on. Algebraic geometry cannot copy these naively, even over the real numbers, since of course the interval [0; 1] on the real line is not defined by a polynomial equation. The only polynomial equal to 0 all over [0; 1] is the constant polynomial 0, thus equals 0 over the whole line. The problem is much worse when you look at algebraic geometry over other fields than the real or complex numbers. Voevodsky shows how category theory allows abstract definitions of the basic apparatus of homotopy, where the category of topological spaces is replaced by any category equipped with objects that share certain purely categorical properties with the unit interval, unit square, and so on. For example, the line in algebraic geometry (over any field) does not have \endpoints" in the usual way but it does come with two naturally distinguished points: 0 and 1. -

Chapter a Preliminaries

Chapter A Preliminaries This chapter introduces the basic set-theoretic nomenclature that we adopt in the present text. As you are more than likely to be familiar with most of what we have to say here, our exposition is rather fast-paced and to the point. Indeed, the majority of this chapter is a mere collection of de…nitions and elementary illustrations, and it contains only a few exercises. It is actually possible that one starts with Chapter B instead, and then comes back to the present chapter when (s)he is not clear about a particular jargon that is used in the body of the text. However, it makes good sense to at least read the part on countable sets below before doing this, because we derive several results there that will be used elsewhere in the book in a routine manner. We begin the chapter with a review of the abstract notions of sets, binary relations, preorders, lattices and functions. As we will work with in…nite products of sets later in the text, we also talk brie‡yabout the Axiom of Choice in our review of set theory. But our presentation focuses mainly on cataloging the basic de…nitions that will be needed later on, and it is duly informal. Besides, we presume in this book that the reader is familiar with the number systems of integers, rational numbers, and real numbers. Nevertheless, after our set theory review, we discuss the algebraic and order-theoretic structure of these systems, putting on record some of their commonly used properties.1 The next stop is the theory of countability, the most important part of this chapter. -

The Magical World of Infinities

The Magical World of Infinities Figure 12 Figure 13 Part II Old monuments, newer buildings, grills on However due to copyright restrictions we cannot Features windows, balcony railings, fences, and so on reproduce photographs of Escher’s work here. It too provide for interesting examples to view via is recommended that the reader peruse his art symmetry. The collage in Figure 12 provides www.mcescher.com. We examples of this and can be analysed in a manner on the official website similar to the earlier collage. puzzle inspired by Escher to enjoy at leisure and to discoverhowever itsleave secrets the reader via symmetry; with an imagesee Figure of a floor13. It would be a grave lacuna not to mention the artwork of M C Escher in an article on symmetry. Shashidhar Jagadeeshan Bibliography Introduction In the previous article we encountered the strange world of 1. M. A. Armstrong, Groups and Symmetry, Springer Verlag, 1988. infinities, where a lot of our intuitive sense of how infinite sets 2. David W. Farmer, Groups and Symmetry: A Guide to Discovering Mathematics, American Mathematical Society, 1995. should behave started breaking down. We saw for example that 3. Joseph A. Gallian, Contemporary Abstract Algebra, 7th edition, Brooks/Cole Cengage Learning, 2010. infinite sets can have subsets which have as many elements asthe original set; we also saw our intuition about length breaking 4. Kristopher Tapp, Symmetry: A Mathematical Exploration, Springer, 2012. down. No matter what the lengths of the two lines are, they 5. Herman Weyl, Symmetry, Princeton University Press, 1952. ended up having the same number of points. -

Lipscomb's L(A) Space Fractalized in Hilbert's I2(A) Space

proceedings of the american mathematical society Volume 115, Number 4, AUGUST 1992 LIPSCOMB'S L(A) SPACE FRACTALIZED IN HILBERT'S I2(A) SPACE S. L. LIPSCOMB AND J. C. PERRY (Communicated by Dennis Burke) Abstract. By extending adjacent-endpoint identification in Cantor's space 7V({0, 1}) to Baire's space N(A), we move from the unit interval / = L({0, 1}) to L(A). The metric spaces L(A)"+l and L(A)°° have provided nonseparable analogues of Nöbeling's and Urysohn's imbedding theorems. To date, however, L(A) has no metric description. Here, we imbed L(A) in l2(A) and the induced metric yields a geometrical interpretation of L(A) . Ex- cept for the small last section, we are concerned with the imbedding. Once inside l2(A), we see L(A) as a subspace of a "closed simplex" AA having the standard basis vectors together with the origin as vertices. The part of L(A) in each «-dimensional face a" of AA is a "generalized Sierpiñski Triangle" called an n-web w" . Topologically, w" is ¿({0, 1, ... , n}). For n = 2, a)2 is just the usual Sierpiñski Triangle in E2 ; for n = 3 , ft)3 is Mandelbrot's fractal skewed web. Thus, L(A) —>12{A) invites an extension of fractals. That is, when \A\ infinite, Baire's Space N(A) is a "generalized code space" on \A\ symbols that addresses the points of the "generalized fractal" L(A). 1. Notation and definitions For any set A , let N(A) be the set of all sequences of elements of A . -

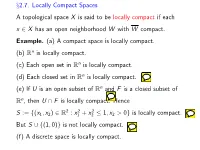

§2.7. Locally Compact Spaces a Topological Space X Is Said to Be Locally Compact If Each X ∈ X Has an Open Neighborhood W with W Compact

x2.7. Locally Compact Spaces A topological space X is said to be locally compact if each x 2 X has an open neighborhood W with W compact. Example. (a) A compact space is locally compact. (b) Rn is locally compact. (c) Each open set in Rn is locally compact. (d) Each closed set in Rn is locally compact. (e) If U is an open subset of Rn and F is a closed subset of Rn, then U \ F is locally compact. Hence f 2 R2 2 2 ≤ g S := (x1; x2) : x1 + x2 1; x2 > 0 is locally compact. But S [ f(1; 0)g is not locally compact. (f) A discrete space is locally compact. (g) Let X be an infinite set with cocountable topology. Then X is not locally compact. Indeed, if x 2 X and if U is a neighborhood of x, then U = X , which is not compact. (h) Let Y be a compact Hausdorff space and let y0 2 Y . Then the subspace X = Y n fy0g is locally compact and Hausdorff. We shall show that every locally compact Hausdorff space arises this way. 7.1. Theorem. Let X be a locally compact Hausdorff space and let Y be a set consisting of X and one other point. Then there exists a unique topology for Y such that Y is a compact Hausdorff space and the relative topology for X inherited from Y coincides with the original topology for X . Proof. The point in Y n X will be labeled 1, the point at infinity.