Planning in Neighborhoods with Multiple Publics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

APPENDIX R.10 List of Recipients for Draft EIS

APPENDIX R.10 List of Recipients for Draft EIS LGA Access Improvement Project EIS August 2020 List of Recipients for Draft EIS Stakeholder category Affiliation Full Name District 19 Paul Vallone District 20 Peter Koo Local Officials District 21 Francisco Moya District 22 Costa Constantinides District 25 Daniel Dromm New York State Andrew M. Cuomo United States Senate Chuck E. Schumer United States Senate Kirsten Gillibrand New York City Bill de Blasio State Senate District 11 John C. Liu State Senate District 12 Michael Gianaris State Senate District 13 Jessica Ramos State Senate District 13 Maria Barlis State Senate District 16 Toby Ann Stavisky State Senate District 34 Alessandra Biaggi State Elected Officials New York State Assembly District 27 Daniel Rosenthal New York State Assembly District 34 Michael G. DenDekker New York State Assembly District 35 Jeffrion L. Aubry New York State Assembly District 35 Lily Pioche New York State Assembly District 36 Aravella Simotas New York State Assembly District 39 Catalina Cruz Borough of Queens Melinda Katz NY's 8th Congressional District (Brooklyn and Queens) in the US House Hakeem Jeffries New York District 14 Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez New York 35th Assembly District Hiram Montserrate NYS Laborers Vinny Albanese NYS Laborers Steven D' Amato Global Business Travel Association Patrick Algyer Queens Community Board 7 Charles Apelian Hudson Yards Hells Kitchen Alliance Robert Benfatto Bryant Park Corporation Dan Biederman Bryant Park Corporation - Citi Field Dan Biederman Garment District Alliance -

Senior Resource Guide

New York State Assemblywoman Nily Rozic Assembly District 25 Senior Resource Guide OFFICE OF NEW YORK STATE ASSEMBLYWOMAN NILY ROZIC 25TH DISTRICT Dear Neighbor, I am pleased to present my guide for seniors, a collection of resources and information. There are a range of services available for seniors, their families and caregivers. Enclosed you will find information on senior centers, health organizations, social services and more. My office is committed to ensuring seniors are able to age in their communities with the services they need. This guide is a useful starting point and one of many steps my office is taking to ensure this happens. As always, I encourage you to contact me with any questions or concerns at 718-820-0241 or [email protected]. I look forward to seeing you soon! Sincerely, Nily Rozic DISTRICT OFFICE 159-16 Union Turnpike, Flushing, New York 11366 • 718-820-0241 • FAX: 718-820-0414 ALBANY OFFICE Legislative Office Building, Room 547, Albany, New York 12248 • 518-455-5172 • FAX: 518-455-5479 EMAIL [email protected] This guide has been made as accurate as possible at the time of printing. Please be advised that organizations, programs, and contact information are subject to change. Please feel free to contact my office at if you find information in this guide that has changed, or if there are additional resources that should be included in the next edition. District Office 159-16 Union Turnpike, Flushing, NY 11366 718-820-0241 E-mail [email protected] TABLE OF CONTENTS (1) IMPORTANT NUMBERS .............................. 6 (2) GOVERNMENT AGENCIES ........................... -

New York State Liquor Authority Full Board Agenda Meeting of 05/27/2020 Referred From: Licensing Bureau

NEW YORK STATE LIQUOR AUTHORITY FULL BOARD AGENDA MEETING OF 05/27/2020 REFERRED FROM: LICENSING BUREAU 2020- 00657 REASON FOR REFERRAL REQUEST FOR DIRECTION QUEENS L 1320133 MCT NEW YORK FINE WINES & FILED: 08/13/2019 SPIRITS LLC 30-02 WHITESTONE EXPRESSWAY FLUSHING, NY 11356 (NEW PACKAGE STORE) The Members of the Authority at their regular meeting held at the Zone 2 Albany Office on 05/27/2020 determined: MEMORANDUM State Liquor ,Authority License Bureau To: Members of the Authority Date: February 12, 2020 From: Adam Roberts, Deputy Commissioner Subject: Queens L 1320133 MCT New York Fine Wines & Spirits LLC DBA: Pending' 30-02 Whitestone Expressway Flushing, NY 11357 Type of Application: New Package Store Question(s) to be considered: Will issuance of this license serve public convenience and advantage? Protests: SUPPORT: Yes Hon. Daniel Rosenthal, NYS Assembly Hon. Nily Rozic, NYS Assembly Hon. Paul Vallone, NYC Council Hon. Donovan Richards, NYC Council Hon. Francisco Moya, NYC Council Thomas Grech, Queens Chamber of Commerce Anthony Road Wine Company (Yates FW 3014271) Victorianbourg Wine Estate LTD (Niagara FW 3144582) PROTESTS: Yes Hon. Grace Meng, US Congress Hon. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, US Congress Hon. Todd Kaminsky, NYS Senate Hon. Toby Ann Stavisky, NYS Senate Hon. John Liu , NYS Senate Ho,n. Michael Gianaris, NYS Senate Hon. Jpseph Addabbo, Jr., NYS Senate Hon. Catalina Cruz, NYS Assembly Hon. Michael Montesano, NYS Assembly Hon. Andrew Raia, NYS Assembly Hon. Jeffrion Aubrey, NYS Assembly Hon. Michele Titus, NYS Assembly Hon. Michael DenDeceker, NYS Assembly Hon. Ron Kim, NYS Assembly Hon. Aravella Simotas, NYS Assembly Hon. -

NYCAR Membership

NYCAR Membership LGA COMMITTEE JFK COMMITTEE U.S. House of Representatives # of Votes U.S. House of Representatives # of Votes US Congressional District 3 1 US Congressional District 3 1 US Congressional District 6 1 US Congressional District 4 1 US Congressional District 8 1 US Congressional District 5 1 US Congressional District 12 1 US Congressional District 5 1 US Congressional District 14 1 Queens Borough President # of Votes Queens Borough President # of Votes Queens Borough President 1 Queens Borough President 1 Queens Borough President 1 Queens Borough President 1 New York State Senate # of Votes New York State Senate # of Votes NYS Senate District 7 1 NYS Senate District 2 1 NYS Senate District 6 1 NYS Senate District 11 1 NYS Senate District 9 1 NYS Senate District 13 1 NYS Senate District 10 1 NYS Senate District 16 1 NYS Senate District 14 1 NYS Senate District 18 1 NYS Senate District 15 1 New York State Assembly # of Votes New York State Assembly # of Votes NYS Assembly District 26 1 NYS Assembly District 19 1 NYS Assembly District 27 1 NYS Assembly District 20 1 NYS Assembly District 34 1 NYS Assembly District 22 1 NYS Assembly District 35 1 NYS Assembly District 23 1 NYS Assembly District 36 1 NYS Assembly District 29 1 NYS Assembly District 40 1 NYS Assembly District 31 1 NYS Assembly District 85 1 NYS Assembly District 32 1 New York City Council # of Votes NYS Assembly District 33 1 NYC Council District 8 1 New York City Council # of Votes NYC Council District 19 1 NYC Council District 27 1 NYC Council District 20 1 -

2015 City Council District Profiles

QUEENS CITY COUNCIL 2015 City Council District Profiles DISTRICT MALBA POWELL’S COVE 21 COLLEGE 14 AVE POINT RIKER’S ISLAND CHANNEL 15 AVE 20 AVE 19 T S Y A FLUSHING BAY East Elmhurst W BOWERY IN STE B AY Jackson Heights LaGuardia North Corona STEINWAY Airport 25 RD Corona LeFrak City D CENTR RAN AL P G KW Y Y PW 6 EX E N EAST O T S 23 AVE ELMHURST E IT H 10 W 24 AVE 19 E BU 96 ST RICSS CURTIS ST 3 TLER ST GILMORE ST 2 20 94 ST 22 95 ST 5 AVE 2 O 93 ST N ST VE A VE 27 38 A 28 100 ST 127 ST 99 ST AS COLLEGE POINT BLVD 98 ST 22 TOR VE IA B VE FLUSHING 31 A LVD A 1 0 106 ST ASTORIA 5 ST 32 AVE HEIGHTS 20 11 23 ORTHERN BLVD 14 N 1 B 1 R 0 ST O WILLETS POINT 90 ST 4 VE O 82 ST 25 T A K 34 AVE 13 VEL L NORTH SE Y OO FLUSHING N CORONA 9 R 1 CREEK Q 12 1 04 ST 112 ST 1 03 ST VE 1 U 5 A 02 ST J 3 01 ST E U E N 7 DR VE N JACKSON 3 A KISSENA BLVD C 38 S T VE VE HEIGHTS A A Y E I 7 9 O 3 3 X N VE W P E A V P W A 40 B ST VE X L 26 R A E Y HU V 41 D VE A K VE M 2 37 A L 9 4 C Legend 7 26 E S 21 Y T VE VE 9 9 3 A 4 A 4 W 4 S 5 S 37 RD 24 5 4 T N T 7 27 AVE AVE A 45 46 1 V 1/4 Mile AVE VE 47 8 A 4 1 9AVE 1 WOODSIDE CORONA 4 1 ST City Council Districts AVE BROADWAY n L AL AVE 15 21 17 P ST E Y N WOODSIDE C City, State, and 5 6 AVE O 50 R Federal Parkland ON M A A E 18 108 ST AV E I V VAN CLEEF ST N IE A n T IS 9 R 8 S 9 PL CH 16 T Playgrounds 9 24 25 7 ELMHURST PL MARTENSE AVE VE n 51 AVE 57 A OTIS AVE Y PW Schoolyards-to-Playgrounds AND EX LEFRAK ISL MEADOW NG n CITY LO LAKE AVE Community Gardens D 29 N A R G n Swimming Pools l D Recreation CentersE 7 CoronaV Golf Playground 15 Josephine Caminiti Plgd 23 Private William Gray AV Parkland L EL B W QUEENS BLVD l JE 1 Flushing Meadows 8 SimeoneN Park 16 Corona Mac Park Park E KEW V Public Plazas Corona Park 9 LouisA Armstrong Plgd 17 William F. -

Statement of Needs for Fiscal Year 2018

INTRODUCTION The annual Statements of Community District Needs (CD Needs Statements) and Community Board Budget Requests (Budget Requests) are Charter mandates that form an integral part of the City's budget process. Together, they are intended to support communities in their ongoing consultations with city agencies, elected officials and other key stakeholders and influence more informed decision making on a broad range of local planning and budget priorities. This report also provides a valuable public resource for neighborhood planning and research purposes, and may be used by a variety of audiences seeking information about New York City's diverse communities. HOW TO USE THIS REPORT This report represents Queens Community Board 7’s Statement of Community District Needs and Community Board Budget Requests for Fiscal Year (FY) 2018. This report contains the formatted but otherwise unedited content provided by the Community Board, collected through an online form available to community boards from September to November 2016. Community boards may provide substantive supplemental information together with their Statements and Budget Requests. This supporting material can be accessed by clicking on the links provided in the document or by copying and pasting them into a web browser, such as Chrome, Safari or Firefox. If you have questions about this report or suggestions for changes please contact: [email protected] This report is broadly structured as follows: a) Overarching Community District Needs Sections 1 – 4 provide an overview of the community district and the top three pressing issues affecting this district overall as identified by the community board. Any narrative provided by the board supporting their selection of their top three pressing issues is included. -

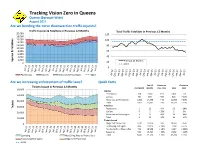

Tracking Vision Zero in Queens

Tracking Vision Zero in Queens Queens (Borough-Wide) August 2017 Are we bending the curve downward on traffic injuries? Traffic Injuries & Fatalities in Previous 12 Months Total Traffic Fatalities in Previous 12 Months 20,000 120 18,000 16,000 100 14,000 12,000 80 10,000 8,000 60 6,000 4,000 40 2,000 Injuries Injuries &Fatalities 20 Previous 12 Months 0 2013 0 Pedestrians Cyclists Motorists & Passengers 2013 Are we increasing enforcement of traffic laws? Quick Facts Past 12 Change vs. Change vs. Tickets Issued in Previous 12 Months This Month Months Prev. Year 2013 2013 60,000 Injuries Pedestrians 168 2,636 + 1% 2,801 - 6% 50,000 Cyclists 90 933 + 8% 826 + 13% 40,000 Motorists and Passengers 1,303 14,298 + 4% 11,895 + 20% Total 1,561 17,867 + 3% 15,522 + 15% 30,000 Fatalities Tickets Pedestrians 3 32 - 6% 52 - 38% 20,000 Cyclists 0 2 - 33% 2 0% Motorists and Passengers 3 21 - 40% 39 - 46% 10,000 Total 6 55 - 24% 93 - 41% Tickets Issued 0 Illegal Cell Phone Use 1,240 14,876 - 2% 26,967 - 45% Disobeying Red Signal 892 11,872 + 14% 7,538 + 57% Not Giving Rt of Way to Ped 754 10,548 + 29% 3,647 + 189% Speeding 961 15,424 + 33% 7,132 + 116% Speeding Not Giving Way to Pedestrians Total 3,847 52,720 + 16% 45,284 + 16% Disobeying Red Signal Illegal Cell Phone Use 2013 Tracking Vision Zero Bronx August 2017 Are we bending the curve downward on traffic injuries? Traffic Injuries & Fatalities in Previous 12 Months Total Traffic Fatalities in Previous 12 Months 12,000 70 10,000 60 8,000 50 6,000 40 4,000 30 20 2,000 Previous 12 Months Injuries Injuries &Fatalities 0 10 2013 0 Pedestrians Cyclists Motorists & Passengers 2013 Are we increasing enforcement of traffic laws? Quick Facts Past 12 Change vs. -

Brownfield Cleanup Program Citizen Participation Plan for 131-10 Avery Avenue

Brownfield Cleanup Program Citizen Participation Plan for 131-10 Avery Avenue February 2019 C241228 131-10 to 131-18 Avery Avenue Flushing Queens, NY 11355 www.dec.ny.gov Citizen Participation Plan – 131-10 to 131-18 Avery Ave, Flushing, NY Contents Section Page Number 1. What is New York’s Brownfield Cleanup Program? ...........................................................3 2. Citizen Participation Activities ...............................................................................................4 3. Major Issues of Public Concern..............................................................................................8 4. Site Information .......................................................................................................................9 5. Investigation and Cleanup Process.......................................................................................14 Appendix A - Project Contacts and Locations of Reports and Information ......................................................................................................................16 Appendix B - Site Contact List ...................................................................................................17 Appendix C - Site Location Map ................................................................................................28 Appendix D - Brownfield Cleanup Program Process ...............................................................29 * * * * * Note: The information presented in this Citizen Participation Plan was -

Chapter 21: Response to Comments1

1 Chapter 21: Response to Comments A. INTRODUCTION This chapter of the Final Environmental Impact Statement (FEIS) summarizes and responds to the substantive oral and written comments received during the public comment period for the Draft Environmental Impact Statement (DEIS) for the USTA Billie Jean King National Tennis Center (NTC) Strategic Vision. The public hearing on the DEIS was held concurrently with the hearing on the project’s Uniform Land Use Review Procedure (ULURP) draft application on April 24, 2013 at Spector Hall at the New York City Department of City Planning (DCP) located at 22 Reade Street, New York, NY 10007. The comment period for the DEIS remained open until 5:00 PM on Monday, May 6, 2013. Written comments received on the DEIS are included in Appendix G. Section B identifies the organizations and individuals who provided relevant comments on the DEIS. Section C contains a summary of these relevant comments and a response to each. These summaries convey the substance of the comments made, but do not necessarily quote the comments verbatim. B. LIST OF ORGANIZATIONS AND INDIVIDUALS WHO COMMENTED ON THE DRAFT ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT STATEMENT ELECTED OFFICIALS 1. Tony Avella, State Senator, oral and written testimony presented by Ivan Acosta dated April 24, 2013 (Avella) 2. Helen Marshall, President, Borough of Queens, written recommendation dated April 11, 2013 (Marshall) COMMUNITY BOARDS 3. Queens Community Board 3 Resolution dated March 18, 2013, and oral testimony by Marta LeBreton, Chair, dated April 24, 2013 (CB3) 4. Queens Community Board 4 Resolution dated March 15, 2013 (CB4) 5. Queens Community Board 6 Resolution dated March 15, 2013 (CB6) 6. -

Download the Commercial Bicyclist Outreach Summary

Do You Deliver? Commercial Bicyclist Outreach Summary Report 1 Announcement of the Program On July 13, 2012, New York City Department of Director Barbara Adler and NYC Hospitality Alliance Transportation Commissioner Janette Sadik-Khan Executive Director Andrew Rigie. The announcement joined Council Members Gale Brewer, Jessica included details of DOT’s new enforcement unit— Lappin, Dan Garodnick and Council Transportation the Commercial Bicycle Unit (CBU)—which began Committee Chairman James Vacca on Manhattan’s their door-to-door educational visits the following Upper West Side to announce that DOT was Monday on the Upper West Side of Manhattan to expanding its safety efforts with New York’s and the distribute materials about the Commercial Bicyclist nation’s largest commercial cycling education and law. Additional education efforts were announced safety campaign. They were joined by a number of including Delivery Cyclist Forums which were supportive businesses including Lenny’s Bagels, Two planned for neighborhoods throughout New York. Boots Pizza, seamless.com and by the Columbus Avenue Business Improvement District Executive City officials announce the commercial Members of the Commercial bicyclist safety effort. Bicycle Unit (CBU). 2 Outreach to Businesses The DOT CBU was deployed to businesses in all Door-to-Door Outreach sections of Manhattan and businesses in select neighborhoods in Brooklyn, Queens and the Bronx. From July 2012 to March 2013, the inspectors Borough Stores Visited went door-to-door to commercial establishments, providing information to hundreds of restaurants Manhattan 2891 and other businesses that employ cyclists. During these visits, they were advised of existing legal Brooklyn 547 requirements to provide safety information and safety equipment to their delivery workers, including Queens 370 helmets, identifying apparel and ID numbers. -

FINAL Aviation Roundtable 01-23-19

Port Authority of NY & NJ FINAL COPY Aviation Roundtable January 23, 2019 Page 1 PORT AUTHORITY OF NEW YORK & NEW JERSEY --------------------------------------------- NEW YORK COMMUNITY AVIATION ROUNDTABLE January 23, 2019 Kew Gardens, New York BEFORE Barbara E. Brown and Warren Schreiber, Co-Chairs JANE ROSE REPORTING Nicole Ellis, Court Reporter FINAL COPY JANE ROSE REPORTING 1-800-825-3341 JANE ROSE REPORTING National Court-Reporting Coverage 1-800-825-3341 [email protected] Port Authority of NY & NJ FINAL COPY Aviation Roundtable January 23, 2019 Page 2 A P P E A R A N C E S: FOR NYCAR JFK INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT COMMITTEE: Nick Felt for Congressman Tom Suozzi Tom Curry for Congresswoman Kathleen Rice Dan Mundy and Patrick Evans and Joseph Edwards for Congressman Gregory Meeks Frieda Menos for Congressman Hakeem Jeffries Gloria Boyce-Charles, Allan Swisher & Dennis Graham for Queens Borough President Melinda Katz Aidan Hughes for Senator Todd Kaminsky Tajuana Hamm for Senator James Sanders Earnest Flowers for Senator Leroy Comrie Barbara E. Brown, Co-Chair, for Assemblywoman Michele Titus Michael Matteo for Assemblywoman Stacey Pheffer Amato Michael Anderson, Town of North Hempstead Richard Smith, Queens Community Board 9 Philippa Karteron, JFK Chamber of Commerce Larry Hoppenhauer, Citizen Member (Appearances continue on following page.) JANE ROSE REPORTING National Court-Reporting Coverage 1-800-825-3341 [email protected] Port Authority of NY & NJ FINAL COPY Aviation Roundtable January 23, 2019 Page 3 A P P E A R A N C E S: (Cont'd.) FOR NYCAR LAGUARDIA AIRPORT COMMITTEE: Justin Connor for Congressman Tom Suozzi Jordan Goldes and Maria Becce for Congresswoman Grace Meng Marie Figueroa for Congressman Hakeem Jeffries Lei Zhao and Susan Carroll for Queens Borough President Melinda Katz Gilbert Hoe for Senator Toby Ann Stavisky Seth Urbinder for Assemblyman Edward Braunstein Tony Cao for Assemblyman Ron Kim J.D. -

2019 Queens Community Board Report

MELINDA KATZ (718) 286-3000 PRESIDENT w eb site: www.queensbp.org e-mail: [email protected] CITY OF NEW YORK OFFICE OF THE PRESIDENT OF THE BOROUGH OF QUEENS 120-5 5 QUEENS BOULEV A RD KEW GARDENS, NEW YORK 11424-1015 To: The Mayor of the City of New York The Speaker of the New York City Council From: The Office of the Queens Borough President Re: 2019 Queens Community Board Report Over the past five years, the Borough President has appointed hundreds of civic-minded individuals to represent their communities on our borough’s 14 Community Boards. Over 300 of these appointments were first-time members, reflecting a commitment to seeking out a diverse group of voices that represent all segments of their respective communities. These efforts have promoted a healthy balance on Community Boards between the useful experience of returning members and the fresh perspectives of new members. The Office of the Queens Borough President issues the following report on Queens Community Boards in 2019 pursuant to the provisions of New York City Charter § 82(17)(a). The demographic information contained in the appendices to this report was collected pursuant to an updated 2019 version of our Community Board application and pertains only to 2019 appointees. § 82(17)(a)(i) Queens Community Board members are appointed to staggered two-year terms each April. Attached to this report is a spreadsheet containing the names of persons serving as Community Board members as of April 1, 2019, the most recent date at which new terms began. For each member, the spreadsheet also indicates attendant information required by the Charter.