A Positive Theory of Religion and Scientific Knowledge

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

German Political and Economic Ideology in the Twentieth Century

EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF CULTURAL AND POLITICAL SOCIOLOGY https://doi.org/10.1080/23254823.2018.1559745 German political and economic ideology in the twentieth century and its theological problems: The Lutheran genealogy of ordoliberalism Troels Krarup Department of Sociology, Copenhagen University, Copenhagen, Denmark ABSTRACT Ordoliberalism is widely considered to be the dominant ideology of the German political elite today and consequently responsible at least in part for its hard ‘austerity’ line during the recent Eurozone crisis. This article presents a genealogy of the main concerns, concepts and problems around which early German ordoliberalism was formed and structured as a political and economic ideology. Early ordoliberalism is shown to be rooted in an interwar Germanophone Lutheran Evangelical tradition of anti-humanist ‘political ethics’. Its specific conceptions of the market, the state, the individual, freedom and duty were developed on a Lutheran Evangelical basis. Analytically, the article considers ideological influences of theology on political and economic theory not so much in terms of consensus and ideational overlap, but rather in terms of shared concerns, concepts and problems across different positions. ARTICLE HISTORY Received 18 March 2018; Accepted 10 December 2018 KEYWORDS Ordoliberalism; ideology; Europe; economic thought; religion; genealogy JEL Classification A12 relation of economics to other disciplines; A13 relation of economics to social values; B29 history of economic thought since 1925: other 1. Introduction: unity and variety in neoliberalism In Colombel’s(1994, p. 128) accurate rephrasing of Foucault’s(1993, p. 35) ‘history of the present’, genealogy is ‘the history of a problem of which the present relevance must be assessed’. One such problem, one that is of major political, cultural and sociological interest in Europe today, relates to the particular German tradition of economic and political thinking termed ordoliberalism. -

A Critique of John Stuart Mill Chris Daly

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC Honors Theses University Honors Program 5-2002 The Boundaries of Liberalism in a Global Era: A Critique of John Stuart Mill Chris Daly Follow this and additional works at: http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/uhp_theses Recommended Citation Daly, Chris, "The Boundaries of Liberalism in a Global Era: A Critique of John Stuart Mill" (2002). Honors Theses. Paper 131. This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the University Honors Program at OpenSIUC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of OpenSIUC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. r The Boundaries of Liberalism in a Global Era: A Critique of John Stuart Mill Chris Daly May 8, 2002 r ABSTRACT The following study exanunes three works of John Stuart Mill, On Liberty, Utilitarianism, and Three Essays on Religion, and their subsequent effects on liberalism. Comparing the notion on individual freedom espoused in On Liberty to the notion of the social welfare in Utilitarianism, this analysis posits that it is impossible for a political philosophy to have two ultimate ends. Thus, Mill's liberalism is inherently flawed. As this philosophy was the foundation of Mill's progressive vision for humanity that he discusses in his Three Essays on Religion, this vision becomes paradoxical as well. Contending that the neo-liberalist global economic order is the contemporary parallel for Mill's religion of humanity, this work further demonstrates how these philosophical flaws have spread to infect the core of globalization in the 21 st century as well as their implications for future international relations. -

Download Article

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research (ASSEHR), volume 252 3rd International Conference on Judicial, Administrative and Humanitarian Problems of State Structures and Economic Subjects (JAHP 2018) The Money Factor from the Perspective of the Adherents of a Subsistence Economy and Mercantilism Yakov Yadgarov Department of Economic Theory Financial University under the Government of the Russian Federation Moscow, Russia E-mail: [email protected] Sergei Tolkachev Vladimir Ostroumov Department of Economic Theory Department of Economic Theory Financial University under the Government of the Russian Financial University under the Government of the Russian Federation Federation Moscow, Russia Moscow, Russia E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Abstract—The purpose of this work is to outline general considering the special role of this factor in all aspects of and special aspects in different perceptions of the place and public life, have also considered the money factor. role of money and money circulation in economic life. This is done by means of historical and economic analysis of the views This is clearly reflected, first, in natural economy "money of the adherents of subsistence economic ideology in the ideology". Towering achievements are considered, from Ancient world and the Middle Ages, as well as of the views of interpretations of the essence and purpose of money by rulers, mercantilists, who were the pioneers of market economic scholars, and philosophers of ancient Oriental and Antique ideology. The objective was to show substantial aspects of public entities until medieval times in those countries in conventional money theory existed in these time periods and which interpretation of the purpose of the money was seen include alternative versions, such as nominalist, metallist, and through the prism of religious, philosophical, and moral- quantity theories. -

“Modern” Economics: Engineering and Ideology

Working Paper No. 62/01 The formation of “Modern” Economics: Engineering and Ideology Mary Morgan © Mary Morgan Department of Economic History London School of Economics May 2001 Department of Economic History London School of Economics Houghton Street London, WC2A 2AE Tel: +44 (0)20 7955 7081 Fax: +44 (0)20 7955 7730 Additional copies of this working paper are available at a cost of £2.50. Cheques should be made payable to ‘Department of Economic History, LSE’ and sent to the Economic History Department Secretary. LSE, Houghton Street, London WC2A 2AE, UK. 2 The Formation of “Modern” Economics: Engineering and Ideology Mary S. Morgan* Economics has always had two connected faces in its Western tradition. In Adam Smith's eighteenth century, as in John Stuart Mill's nineteenth, these might be described as the science of political economy and the art of economic governance. The former aimed to describe the workings of the economy and reveal its governing laws while the latter was concerned with using that knowledge to fashion economic policy. In the twentieth century these two aspects have more often been contrasted as positive and normative economics. The continuity of these dual interests masks differences in the way that economics has been both constituted and practiced in the twentieth century when these two aspects of economics became integrated in a particular way. Originally a verbally expressed body of scientific law-like doctrines and associated policy arts, in the twentieth century these two wings of economics became conjoined by a set of technologies routinely and widely used within the practice of economics in both its scientific and policy domains. -

The Neo-Liberal State in a Post-Global World

ISSN 2029–2236 (print) ISSN 2029–2244 (online) Socialinių mokslų studijos SOCIAL SCIENCES STUDIES 2010, 3(7), p. 7–17. THE NEO-LIBERAL STATE IN A POST-GLOBAL WORLD David Schultz Hamline University School of Business 1536 Hewitt Avenue, Saint Paul, MN 55104-1284 Minnesota, United States of America Phone (+1651) 5232 858 Email [email protected] Received 3 August, 2010; accepted 20 September, 2010 Abstract. Neo-liberalism has been the dominant political–economic ideology defining the state and the world economy since the late 1970s. Neo-liberalism is a political–economic theory committed to laissez-faire market fundamentalism, a minimalist role for state inter- vention into the economy, and free trade and open borders. The global financial crisis that began in 2008 challenges the neo-liberal views of the state in numerous ways. This article describes the rise of the neo-liberal state, the ways the global crisis created a crisis for it, and then how the response to it questions its legitimacy and viability. The article concludes with detailing the various problems with neo-liberalism, calling for a rethinking of state theory within a new post-global economic order. Keywords: neo-liberalism, state, globalization, globalism, global financial crisis, poli- tics, economics. Introduction The western banking crisis that began in 2008 and the global recession produced as a result is an historic event on two counts. First, state intervention to save the banks, including the 2008 Troubled Assets Relief Fund and the 2010 Wall Street and Consumer Protection Act in the U.S., represented the most significant bailout and reregulation of Socialinių mokslų studijos/Social Sciences Studies ISSN 2029–2236 (print), ISSN 2029–2244 (online) Mykolo Romerio universitetas, 2010 http://www.mruni.eu/lt/mokslo_darbai/SMS/ Mykolas Romeris University, 2010 http://www.mruni.eu/en/mokslo_darbai/SMS/ David Schultz. -

The Fair and Laissez-Faire Markets: from a Neoliberal Laissez- Faire Baseline to a Fair Market

Pursuit - The Journal of Undergraduate Research at The University of Tennessee Volume 5 Issue 1 Article 8 June 2014 The Fair and Laissez-Faire Markets: From a Neoliberal Laissez- Faire Baseline to a Fair Market Eric L. Dixon University of Tennessee, Knoxville, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/pursuit Part of the Economic Policy Commons, Economic Theory Commons, Ethics and Political Philosophy Commons, Inequality and Stratification Commons, Political Economy Commons, and the Public Policy Commons Recommended Citation Dixon, Eric L. (2014) "The Fair and Laissez-Faire Markets: From a Neoliberal Laissez-Faire Baseline to a Fair Market," Pursuit - The Journal of Undergraduate Research at The University of Tennessee: Vol. 5 : Iss. 1 , Article 8. Available at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/pursuit/vol5/iss1/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Volunteer, Open Access, Library Journals (VOL Journals), published in partnership with The University of Tennessee (UT) University Libraries. This article has been accepted for inclusion in Pursuit - The Journal of Undergraduate Research at The University of Tennessee by an authorized editor. For more information, please visit https://trace.tennessee.edu/pursuit. The Fair and Laissez-Faire Markets: From a Neoliberal Laissez-Faire Baseline to a Fair Market Cover Page Footnote I would like to thank David Reidy, Jon Garthoff, and especially Jon Shefner for their continued assistance of my studies in political economy and political philosophy. I would also like to thank my friends and family for their unconditional support. This article is available in Pursuit - The Journal of Undergraduate Research at The University of Tennessee: https://trace.tennessee.edu/pursuit/vol5/iss1/8 Pursuit: The Journal of Undergraduate Research at the University of Tennessee Copyright © The University of Tennessee PURSUIT trace.tennessee.edu/pursuit Fair & Laissez-Faire Markets: From a laissez-faire baseline to a fair market conception ERIC L. -

Henry George - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Henry George - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Henry_George Henry George From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Henry George Henry George (September 2, 1839 – October 29, 1897) was an American writer, politician and political Classical economics economist, who was the most influential proponent of the land value tax, also known as the "Single Tax" on land. He inspired the philosophy and economic ideology known as Georgism, that holds that everyone owns what they create, but that everything found in nature, most importantly land, belongs equally to all humanity. His most famous work is Progress and Poverty written in 1879; it is a treatise on inequality, the cyclical nature of industrial economies and possible remedies. Contents 1 Biography Henry George 2 Policy proposals 2.1 Monopolies Birth September 21, 1839 2.2 Chinese immigration Death October 29, 1897 (aged 58) 2.3 The Single Tax on Land 2.4 Free Trade Nationality American 2.5 Secret Ballots Contributions Georgism; studied land as a factor in 3 Political career economic inequality and business 4 Subsequent influence cycles; proposed land value tax 5 Economic contributions 6 Notes 7 References 8 Bibliography 9 See also 10 External links Biography George was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania to a lower-middle class family, the second of ten children of Richard S. H. George and Catharine Pratt (Vallance) George. His formal education ended at age 14 and he went to sea as a foremast boy at age 15 in April 1855 on the Hindoo, bound for Melbourne and Calcutta. He returned to Philadelphia after 14 months at sea to become an apprentice typesetter before settling in California. -

Michael Hudson 17/09/13 2:58 PM

The Mathematical Economics of Compound Rates of Interest: A Four-Thousand Year Overview Part I | Michael Hudson 17/09/13 2:58 PM Log In Michael Hudson On finance, real estate and the powers of neoliberalism Home About Books Interviews Speeches RSS The Mathematical Economics of Compound Rates of Interest: A Four-Thousand Year Overview Part I January 24, 2004 By Michael “Whoever enters here must know mathematics.” That was the motto of Plato’s Academy. Emphasizing such abstract ratios as the Pythagorean proportions of musical temperament and the calendrical regularities of the sun, moon and planets, its philosophy used the mathematics of nature to reveal an underlying harmony and order in the universe and hence, in an ideal society. But there was little quantitative analysis of economic relations. Although the Greek and Roman economies were increasingly wracked by debt, there was no measurement of this phenomenon, or of overall production, distribution and other macroeconomic measures. The education of modern economists still consists largely of higher mathematics whose use remains more metaphysical than empirically measuring the most important trends. Over a century ago John Shield Nicholson (1893:122) remarked that “The traditional method of English political economy was more recently attacked, or rather warped,” by pushing the hypothetical or deductive side . to an extreme by the adoption of mathematical devices. less able mathematicians have had less restraint and less insight; they have mistaken form for substance, and the expansion of a series of hypotheses for the linking together of a series of facts. This appears to me to be especially true of the mathematical theory of utility. -

Ecological Economics

ECOLOGICAL ECONOMICS http://greenplanet.eolss.net.login.ezproxy.library.ualbert... Search Print this chapter Cite this chapter ECOLOGICAL ECONOMICS Brian Czech Center for the Advancement of the Steady State Economy, 5101 South 11th Street., Arlington, Virginia 22204, USA Keywords: allocation of resources, distribution of wealth, ecological economics, ecological footprint, economic growth, ecosystem services, limits to growth, natural capital, optimum scale, steady state economy Contents 1. Historical Development of Ecological Economics 2. Approach and Philosophy of Ecological Economics 3. Themes and Emphases of Ecological Economics 4. Policy Implications of Ecological Economics 5. Future Directions and Challenges for Ecological Economics 6. Conclusion Acknowledgements Related Chapters Glossary Bibliography Biographical Sketch Summary Ecological economics arose in the final decades of the 20th century out of concerns for environmental protection and economic sustainability. It was largely a response to a real or perceived lack of physical and biological underpinnings in neoclassical economics. It was also intended to infuse economics with a moral philosophy, in contrast with the amoral implications of neoclassical models portraying man as a rational, utility-maximizing automaton. Ecological economics is a transdisciplinary endeavor, incorporating and synthesizing concepts and findings from an array of natural and social sciences. Of particular importance are the laws of thermodynamics and basic principles of ecology. Limits to economic growth are thoroughly understood only via the first two laws of thermodynamics. The first law establishes that there is a limit to the inputs required for economic production, and the second law establishes that there are limits to the efficiency with which those inputs may be transformed into goods and services. -

Fads and Fashions: If They Are So Bad, Why Are They So Rapidly Rich? Transcript

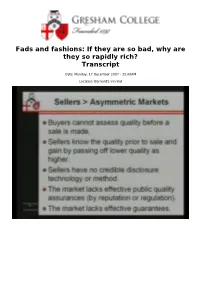

Fads and fashions: If they are so bad, why are they so rapidly rich? Transcript Date: Monday, 17 December 2007 - 12:00AM Location: Barnard's Inn Hall FADS AND FASHIONS: IF THEY ARE SO BAD, WHY ARE THEY SO RAPIDLY RICH? Professor Michael Mainelli Good evening Ladies and Gentlemen. I’m pleased to find so many of you gave up an evening’s Christmas shopping for this year’s Annual Gresham College Buzz Lightyear Lecture. But we’ll come to fads in a moment. As you know, it wouldn’t be a Commerce lecture without a commercial. So I’m glad to announce that the next Commerce lecture will continue our theme of better choice next month. That talk is “Perfectly Unpredictable: Why Forecasting Produces Useful Rubbish”, here at Barnard’s Inn Hall at 18:00 on Monday, 28 January. An aside to Securities and Investment Institute, Association of Chartered Certified Accountants and other Continuing Professional Development attendees, please be sure to see Geoff or Dawn at the end of the lecture to record your CPD points or obtain a Certificate of Attendance from Gresham College. Well, as we say in Commerce – “To Business”. We all know that celebrities, sports stars, estate agents, bankers, lawyers and accountants, along with CEO fat cats, are overpaid. But can we explain why? One of the great things about fads, fashions and excessive pay is that it gives us an excuse tonight to explore two key points in commerce, namely information asymmetry and positional goods. Information Asymmetry [SLIDE: TRUST IN RATIONALITY] Before we start with information asymmetry, I’d like to share a little puzzle about trust, deterrence and rationality to warm you up. -

Ideology, Class, Crisis and Power: the Role of the Print Media in the Representation of Economic Crisis and Political Policy in Ireland (2007-2009)

Ideology, Class, Crisis and Power: The Role of the Print Media in the Representation of Economic Crisis and Political Policy in Ireland (2007-2009). Henry Silke BA (Hons) This thesis is submitted to Dublin City University for the award of a Ph.D in the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences. January 2015 School of Communications Supervisor: Prof. Paschal Preston 1 I hereby certify that that this material, which I now submit for assessment on the programme of study leading to the award of Ph.D is entirely my own work, and that I have exercised reasonable care to ensure that the work is original, and does not to the best of my knowledge breach any law of copyright, and has not been taken from the work of others save and to the extent that such work has been cited and acknowledged within the text of my work. Signed:_________________________________ (Candidate) ID No.: 56109342 Date: ________________ 2 Chapter Chapter Title Sub- Sub-Chapter Title Chapter 1 Introduction 11 2 Politics Power and Ideology 2.1 The State, Class and Political 25 Power 2.2 The Invisible Conflict: Theories 47 of Ideology, Hegemony & Discourse 3 Economics, World Systems and Crisis 3.1 A House or a Home? Use 71 Value/Exchange Value and Crisis Theory 3.2 World System Theory, 84 Finacialisation, Hegemony and Crisis 3.3 3.3 Dependency and Crisis: Irish 90 Political Economy in the Neoliberal Age 4 The Media: Structure, Politics, Power and 4.1 Critical Political Economy and 112 Crisis the study of Communications and the Media 4.2 The Role of the Media in Market 137 Systems -

Changing Forms of State Intervention in Capitalist Economies

Canadian Journal of Political and Social Theory/Revue canadienne de theorie politique et sociale, Vol. 5, Nos. 1 - 2 (Winter/ Spring, 1981). MERCANTILISM, LIBERALISM AND KEYNESIANISM: CHANGING FORMS OF STATE INTERVENTION IN CAPITALIST ECONOMIES David A. Wolfe The distinctive feature of political experience in advanced capitalist society is the extent to which state activity pervades virtually all aspects of social, cultural and economic life. The predominant role of the state in contemporary capitalist society is a far cry from the role ascribed to it during the nineteenth century, when it was subordinate to the self-regulating market. This development has posed a grave dilemma for the contractarian political theory of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, informed by the conception ofthe self-regulating market, which provided the basis for the development of modern liberal democratic political institutions . According to contractarian theory, these liberal democratic political institutions - political parties, elections, representative assemblies and a responsible executive - determine the policy role of the state. They fulfill in effect a dual role, providing the means for the expression and authoritative resolution of political differences while simultaneously providing the means to ensure that the results of the political decision-making process are regarded as just and legitimate. The expansion of the areas ofstate involvement in the economy throughout this century is largely the result of the political pressures imposed upon the state through the operation of representative political institutions. The extension of the mass franchise and the consequent development of mass- based political parties provided the mechanism by which those groups in society which were most vulnerable to the unimpeded operation of the self- regulating market could utilize the state to defend themselves .