The Creation Account in Genesis 1: Our World Only Or the Universe?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cleansing the Cosmos

CLEANSING THE COSMOS: A BIBLICAL MODEL FOR CONCEPTUALIZING AND COUNTERACTING EVIL By E. Janet Warren A thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Theology and Religion College of Arts and Law The University of Birmingham November 14, 2011 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSRACT Understanding evil spiritual forces is essential for Christian theology. Evil has typically been studied either from a philosophical perspective or through the lens of ‘spiritual warfare’. The first seldom considers demonology; the second is flawed by poor methodology. Furthermore, warfare language is problematic, being very dualistic, associated with violence and poorly applicable to ministry. This study addresses these issues by developing a new model for conceptualizing and counteracting evil using ‘non-warfare’ biblical metaphors, and relying on contemporary metaphor theory, which claims that metaphors are cognitive and can depict reality. In developing this model, I examine four biblical themes with respect to alternate metaphors for evil: Creation, Cult, Christ and Church. Insights from anthropology (binary oppositions), theology (dualism, nothingness) and science (chaos-complexity theory) contribute to the construction of the model, and the concepts of profane space, sacred space and sacred actions (divine initiative and human responsibility) guide the investigation. -

Three Versions of Versions of Versions of the Book of Genesis The

Three Versions of the Book of Genesis Below are three versions of the same portion of chapter 1 of Genesis. King James Version: The Creation 1 In the beginning God created the heaven and the earth. 2 And the earth was without form, and void; and darkness was upon the face of the deep. And the Spirit of God moved upon the face of the waters. 3 And God said, Let there be light: and there was light. 4 And God saw the light, that it was good: and God divided the light from the darkness. 5 And God called the light Day, and the darkness he called Night. And the evening and the morning were the first day. 6 And God said, Let there be a firmament in the midst of the waters, and let it divide the waters from the waters. 7 And God made the firmament, and divided the waters which were under the firmament from the waters which were above the firmament: and it was so. 8 And God called the firmament Heaven. And the evening and the morning were the second day. 9 And God said, Let the waters under the heaven be gathered together unto one place, and let the dry land appear: and it was so. 10 And God called the dry land Earth; and the gathering together of the waters called he Seas: and God saw that it was good. http://www.bartleby.com/108/01/1.html#1 Contemporary English VersionVersion:::: 1 In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth. -

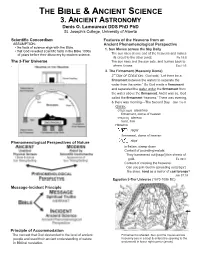

Ancient Science 3 ASTRO

THE BIBLE & ANCIENT SCIENCE 3. ANCIENT ASTRONOMY Denis O. Lamoureux DDS PhD PhD St. Joseph’s College, University of Alberta Scientific Concordism Features of the Heavens from an ASSUMPTION: Ancient Phenomenological Perspective • the facts of science align with the Bible. 1. Sun Moves across the Sky Daily • that God revealed scientific facts in the Bible 1000s of years before their discovery by modern science. The sun rises at one end of the heavens and makes its circuit to the other [end]. Ps 19:6 The 3-Tier Universe The sun rises and the sun sets, and hurries back to . where it rises. Eccl 1:5 2. The Firmament (Heavenly Dome) 2ND DAY OF CREATION: God said, “Let there be a firmament between the waters to separate the water from the water.” So God made a firmament and separated the water under the firmament from the water above the firmament. And it was so. God called the firmament ‘heavens.’ There was evening, & there was morning––The Second Day. Gen 1:6-8 GREEK στερεωμα stereōma firmament, dome of heaven στερεος stereos hard, firm HEBREW rāqîa‘ firmament, dome of heaven Phenomenological Perspectives of Nature rāqa‘ to flatten, stamp down Context of pounding metals: They hammered out [rāqa‘] thin sheets of gold. Ex 39:3 Context of creating the heavens: Can you join God in spreading out [rāqa‘] the skies, hard as a mirror of cast bronze? Job 37:18 Egyptian 3-Tier Universe (1570-1085 BC) Message-Incident Principle Principle of Accommodation The concept that God descended to the level of ancient Firmament is shaded. -

THE FIRMAMENT and the WATER ABOVE Part I: the Meaning of Raqiac in Gen 1:6-8

The Westminster Theological Journal 53 (1991) 227-40 Copyright © 1991 by Westminster Theological Seminary, cited with permission. WTJ 53 (1991) 227-240 THE FIRMAMENT AND THE WATER ABOVE Part I: The Meaning of raqiac in Gen 1:6-8 PAUL H. SEELY STANDARD Hebrew lexica and a number of modern biblical scholars c have defined the raqia (fyqr, "firmament") of Gen 1:6-8 as a solid dome over the earth.1 Conservative scholars from Calvin on down to the present, however, have defined it as an atmospheric expanse.2 Some conservatives have taken special pains to reject the concept of a solid dome on the basis that the Bible also refers to the heavens as a tent or curtain and that refer- ences to windows and pillars of heaven are obviously poetic.3 The word raqiac, they say, simply means "expanse." They say the understanding of raqiac as a solid firmament rests on the Vulgate's translation, firmamentum; and that translation rests in turn on the LXX's translation stere<wma, which simply reflected the Greek view of the heavens at the time the trans- lators did their work.4 The raqiac defined as an atmospheric expanse is the historical view according to modern conservatives; and the modern view of the raqiac as a solid dome is simply the result of forcing biblical poetic language into agreement with a concept found in the Babylonian epic Enuma Elish.5 The historical evidence, however, which we will set forth in concrete detail, shows that the raqiac was originally conceived of as being solid and not a merely atmospheric expanse. -

Tanya Sources.Pdf

The Way to the Tree of Life Jewish practice entails fulfilling many laws. Our diet is limited, our days to work are defined, and every aspect of life has governing directives. Is observance of all the laws easy? Is a perfectly righteous life close to our heart and near to our limbs? A righteous life seems to be an impossible goal! However, in the Torah, our great teacher Moshe, Moses, declared that perfect fulfillment of all religious law is very near and easy for each of us. Every word of the Torah rings true in every generation. Lesson one explores how the Tanya resolved these questions. It will shine a light on the infinite strength that is latent in each Jewish soul. When that unending holy desire emerges, observance becomes easy. Lesson One: The Infinite Strength of the Jewish Soul The title page of the Tanya states: A Collection of Teachings ספר PART ONE לקוטי אמרים חלק ראשון Titled הנקרא בשם The Book of the Beinonim ספר של בינונים Compiled from sacred books and Heavenly מלוקט מפי ספרים ומפי סופרים קדושי עליון נ״ע teachers, whose souls are in paradise; based מיוסד על פסוק כי קרוב אליך הדבר מאד בפיך ובלבבך לעשותו upon the verse, “For this matter is very near to לבאר היטב איך הוא קרוב מאד בדרך ארוכה וקצרה ”;you, it is in your mouth and heart to fulfill it בעזה״י and explaining clearly how, in both a long and short way, it is exceedingly near, with the aid of the Holy One, blessed be He. "1 of "393 The Way to the Tree of Life From the outset of his work therefore Rav Shneur Zalman made plain that the Tanya is a guide for those he called “beinonim.” Beinonim, derived from the Hebrew bein, which means “between,” are individuals who are in the middle, neither paragons of virtue, tzadikim, nor sinners, rishoim. -

Biblical Cosmology: the Implications for Bible Translation

Journal of Translation, Volume 9, Number 2 (2013) 1 Biblical Cosmology: The Implications for Bible Translation John R. Roberts John Roberts is a Senior Linguistics Consultant with SIL International. He has a Ph.D. in Linguistics from University College London. From 1978 to 1998 John supervised the Amele language project in Papua New Guinea during which time translations of Genesis and the New Testament were completed. John has taught graduate level linguistics courses in the UK, USA, Sweden, S. Korea and W. Asia. He has published many articles in the domains of descriptive linguistics and Bible translation and several linguistics books. His current research interest is to understand Genesis 1–11 in an ancient Near East context. Abstract We show that the creation account in Genesis 1.1–2.3 refers to a worldview of the cosmos as the ancient Mesopotamians and ancient Egyptians understood it to be. These civilisations left behind documents, maps and iconography which describe the cosmological beliefs they had. The differences between the biblical cosmology and ancient Near East cosmologies are observed to be mainly theological in nature rather than cosmological. However, the biblical cosmology is conceptually different to a modern view of the cosmos in significant ways. We examine how a range of terms are translated in English Bible translations, including ḥōšeḵ, təhôm, rāqîᵃʿ, hammayim ʾăšer mēʿal lārāqîᵃʿ, and mayim mittaḥaṯ lā’āreṣ, and show that if the denotation of these terms is in accordance with a modern worldview then this results in a text that has incongruities and is incoherent in the nature of the cosmos it depicts. -

Living Under Vacant Skies

Living Under Vacant Skies When, in the biblical cosmology, God creates heaven and earth, “heaven” names that part of creation in which God alone exer- cises dominion, and which we do not know intimately until we are at last fully reconciled to God. As our culture loses this sense Christian Reflection of heaven “over us,” it will be more than a change in how we A Series in Faith and Ethics picture the world in our minds. It will reshape the way we live. Prayer Scripture Reading: Acts 17:16-34 Responsive Reading† Not to us, O LORD, not to us, but to your name give glory, for Focus Article: the sake of your steadfast love and your faithfulness. Living Under Vacant Why should the nations say, “Where is our God?” Our God Skies is in the heavens; he does whatever he pleases. (Heaven and Hell, pp. 9- Their idols are silver and gold, the work of human hands. 17) They have mouths, but do not speak; eyes, but do not see. They have ears, but do not hear; noses, but do not smell. Suggested Article: They have hands, but do not feel; feet, but do not walk; Nothing But the Truth they make no sound in their throats. (Heaven and Hell, pp. 79- Those who make them are like them; 83) so are all who trust in them. We, who fear the LORD, will trust in the LORD! He is our help and shield. May you be blessed by the LORD, who made heaven and earth. The heavens are the LORD’s heavens, but the earth he has given to human beings. -

Adam and Eve—Community: Reading Genesis

last day of creative work. In the second account, however, Man is created before anything else.2 Of course, it is not to be denied that the text did not spring up ex nihilo, created by a Volume 1, Issue 1 | Fall 2003 writer without reference to previous texts. The redactor undoubtedly had a number of Adam and Eve—Community: texts to which he could refer in creating the Reading Genesis 2-3 Genesis text, and he undoubtedly used works already familiar to him as sources. Or James E. Faulconer it is conceivable that there was no individual Brigham Young University redactor or set of redactors, but only the egin thinking about human community solidifying of an oral tradition. For our B and its possibility at the beginning, or purposes, it does not matter. In either case it almost at the beginning, one step after the is too much to assume that the final text is immemorial beginning.1 The biblical story merely contradictory. There may be of the creation of Man (’adam) and Woman contradictions within the text, but the more (’isha) and their expulsion from the garden obvious those contradictions are, the less places humans in the world in a particular likely it is that they are contradictions that way; it creates a habitation for human life so undo the text. It is too much to assume that that the history shared by humans and the the redaction of Genesis was a product of story that manifests community includes the blindness. A considerable amount of “cut possibility of gathering together all humans and paste” work was surely involved in the as unique individuals rather than simply as creation of the Genesis story, but unless we members of a collective. -

Heaven and Hell These Guides Integrate Bible Study, Prayer, and Worship to Help Us Treat the Transcendent Realities of Heaven and Hell Carefully and Seriously

Study Guides for Heaven and Hell These guides integrate Bible study, prayer, and worship to help us treat the transcendent realities of heaven and hell carefully and seriously. The guides can be used in a series or individually. Christian Reflection You may reproduce them for personal or group use. A Series in Faith and Ethics Living Under Vacant Skies 2 As our culture loses the thought of heaven “over us,” how does that shape the way we live? A world left without a vision of the transcendent is a world of struggles without victory and of sacrifice without purpose. To understand this is also to understand in a new way the task of the church. The Virtue of Hope 4 If we are to pursue our moral life seriously, we need a transcendent hope that is not based on human capacity for self-improvement. We have grounds in our faith for such a hope, both at the individual level and at the level of society. Heaven is Our Home 6 Is our true home in heaven, and we are merely sojourners on earth? Or are we genuinely citizens of the earth? Where is our true home? The biblical message is that heaven is our true home, but heaven begins here on earth as the Holy Spirit transforms us into a community that manifests love. Unquenchable Fire 8 We have many questions about hell. We can begin to answer these questions by studying the biblical passages about Sheol, Hades, and Gehenna. The Gates of Hell Shall Not Preva il 10 The universe and our lives ultimately are bounded by God’s unfathomable love and righteousness. -

Daily Devotional, December 24, 2020 Christmas Eve Thoughts

Daily Devotional, December 24, 2020 Christmas Eve Thoughts It is my hope that each of you, has a meaningful and blessed Christmas. Although many of you, like myself, will not be spending time together with loved ones this year, things will change soon, and we will all find opportunities in the future to make up for lost time. Let’s make sure we do not let those opportunities slip away. The prayer below did not originate with me; it was given by NASA Astronaut Frank Borman of Apollo 8, the first manned space mission to orbit Earth's moon, in a live telecast on Christmas Eve 1968 His fellow astronauts shared relevant Biblical passages. The prayer and Scriptures are still appropriate for us in 2020. William Anders: "For all the people on Earth the crew of Apollo 8 has a message we would like to send you". "In the beginning God created the heaven and the earth. And the earth was without form, and void; and darkness was upon the face of the deep. And the Spirit of God moved upon the face of the waters. And God said, “’Let there be light’: and there was light. And God saw the light, that it was good: and God divided the light from the darkness.” Jim Lovell: “And God called the light Day, and the darkness he called Night. And the evening and the morning were the first day. And God said, “’Let there be a firmament in the midst of the waters, and let it divide the waters from the waters”’. -

Recent Scholarly Perspectives on Genesis

Recent Scholarly Perspectives on Genesis Dr. Steven Ball Professor of Physics Photo by Shai Halevi, courtesy of Israel Antiquities Authority Sabbatical – Time to Play Sabbatical – Time to Sightsee Sabbatical – Time to Work Sabbatical – Time to Teach Sabbatical – Time to Learn Overview of Genesis • Genesis is the first book of the Pentateuch, a five-part collection on the birth of the nation of Israel – from Creation to Israel entering Canaan • Authorship is traditionally attributed to Moses, following the exodus of Israel from Egypt, around 1400 BCE. • Most modern scholars accept that Genesis is a redacted literary work, reaching its final version as late as post-exilic Israel around 400 BCE. Overview of Genesis • Genesis 1-11 is a brief outline of history beginning with creation, the fall and the spread of sin, to the origin of people groups and languages, all in need of redemption. • Genesis 12-50 are the patriarchal stories: God partners with Abraham, Isaac, Jacob & Joseph, in establishing Israel and a plan of redemption. • Understanding the purpose and meaning of Genesis has been a challenge for Bible scholars long before the advent of modern science. Genesis 1 – Creation • “In the beginning God created the heavens and earth. And the earth was formless and void…” • The “formless void” is transformed by God over 6 days into an earth that is ordered and filled. • 7 times “God saw that it was good” • Each “day” is described as “and there was evening and there was morning” • Man is created “in the image of God” • God “rests” on the seventh day, blessing it Pattern of each day § 1. -

Book Reviews

Book Reviews encing biblical texts, touching on theological history, Franklin writes that evangelical ecclesiological imagi- relevant to contemporary faith-science conversations nation must expand and deepen. That is true not only about human origins and destiny, and passionately for evangelical theologians but for all of us in differ- attuned to the importance of its subject matter for ent regions of the worldwide church. Our thinking the oppressed and the vulnerable, it deserves a wide about the church has been too small. What is the best readership. strategy to expand and deepen our ecclesial imagi- Reviewed by Patrick S. Franklin, Associate Professor of Theology and nation? Franklin gives it an injection of Bonhoeffer Ethics, Providence Seminary, Otterburne, MB R0A 1G0. and others. Is that suffi cient? I do not think so. What is missing is a broader ecumenical perspective that takes seriously more of the Eastern Orthodox, BEING HUMAN, BEING CHURCH: The Signifi - Roman Catholic, and Anglican theological traditions cance of Theological Anthropology for Ecclesiology whose strong suit is and has always been ecclesiol- by Patrick S. Franklin. Carlisle, UK: Paternoster, 2016. ogy. Granted, Pannenberg and Moltmann are both 325 pages. Paperback; $49.99. ISBN: 9781842278420. ecumenical theologians who have invested a lot of The theme of this book is that a theologically ade- thought in doing just that. Pannenberg especially has quate doctrine of the church presupposes an equally been at the forefront of ecumenical dialogue, a leader adequate doctrine of the human person. The mean- in Faith and Order and a member of the Catholic- ing of being human has a decisive bearing on the Lutheran Dialogue, both of which rank ecclesiology meaning of being church.