A Response to Homelessness in Pinellas County, Florida

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

22 Citizens Guide Here

County Cities & Towns General Information Clearwater is the county seat. PinellasCounty.org *Election dates vary by municipality. Call to confirm election dates. Voter Eligibility: You are eligible to register to vote if you are a U.S. citizen, age 18 or older, and a legal resident of the county Offices for County Commissioners and Administrator Belleair: (727) 588-3769 315 Court St., Clearwater, FL 33756 (727) 464-3000 901 Ponce de Leon Blvd., 33756 in which you want to register. Belleair Beach: (727) 595-4646 Florida’s Closed Primary Elections: Although party affiliation Pinellas County Commissioners 4-year term 444 Causeway Blvd., 33786 is not a registration requirement, only voters registered District 1 Janet C. Long (D) 2024 (727) 464-3365 Belleair Bluffs: (727) 584-2151 with a political party can vote in that party’s primary District 2 Patricia “Pat” Gerard (D) 2022 (727) 464-3360 2747 Sunset Blvd., 33770 elections. All eligible voters, regardless of party affiliation, District 3 Charlie Justice (D) 2024 (727) 464-3363 Belleair Shore: (727) 593-9296 may vote in nonpartisan contests, and universal primary District 4 Dave Eggers (R) 2022 (727) 464-3276 1200 Gulf Blvd., 33786 elections in which all candidates for an office have the same District 5 Karen Williams Seel (R) 2024 (727) 464-3278 Clearwater: (727) 562-4092 2021 - 2022 District 6 Kathleen Peters (R) 2022 (727) 464-3568 600 Cleveland St., 6th Floor, 33755 party affiliation, if the winner of the primary will have no District 7 René Flowers (D) 2024 (727) 464-3614 Mail: P.O. Box 4748, 33758 opposition in the general election. -

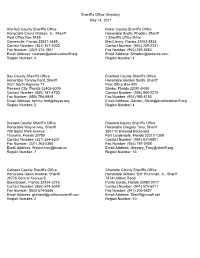

Sheriff's Office Directory

Sheriff’s Office Directory May 14, 2021 Alachua County Sheriff's Office Baker County Sheriff's Office Honorable Clovis Watson, Jr., Sheriff Honorable Scotty Rhoden, Sheriff Post Office Box 5489 1 Sheriff's Office Drive Gainesville, Florida 32627-5489 MacClenny, Florida 32063-8833 Contact Number: (352) 367-4000 Contact Number: (904) 259-2231 Fax Number: (352) 374-1801 Fax Number: (904) 259-5583 Email Address: [email protected] Email Address: [email protected] Region Number: 4 Region Number: 4 Bay County Sheriff's Office Bradford County Sheriff's Office Honorable Tommy Ford, Sheriff Honorable Gordon Smith, Sheriff 3421 North Highway 77 Post Office Box 400 Panama City, Florida 32405-5009 Starke, Florida 32091-0400 Contact Number: (850) 747-4700 Contact Number: (904) 966-2276 Fax Number: (850) 784-0949 Fax Number: (904) 966-6160 Email Address: [email protected] Email Address: [email protected] Region Number: 2 Region Number: 4 Brevard County Sheriff's Office Broward County Sheriff's Office Honorable Wayne Ivey, Sheriff Honorable Gregory Tony, Sheriff 700 South Park Avenue 2601 W Broward Boulevard Titusville, Florida 32780 Fort Lauderdale, Florida 33312-1308 Contact Number: (321) 264-5201 Contact Number: (954) 831-8901 Fax Number: (321) 264-5360 Fax Number: (954) 797-0936 Email Address: [email protected] Email Address: [email protected] Region Number: 7 Region Number: 13 Calhoun County Sheriff's Office Charlotte County Sheriff's Office Honorable Glenn Kimbrel, Sheriff Honorable William "Bill" Prummell, -

Public Involvement Program

Public Involvement Program I-275 / SR93 From South of 54th Avenue South to North of 4th Street North Pinellas County, Florida PROJECT DEVELOPMENT & ENVIRONMENT (PD&E) STUDY April 2016 Work Program Item No: 424501-1 Public Involvement Program I-275 / SR93 PD&E Study Contents I Description of Proposed Improvement ................................................................................................ 1 II Project Background ............................................................................................................................. 4 Tampa Bay Express (TBX) Master Plan ............................................................................................. 4 TBX Master Plan Project ........................................................................................................... 4 TBX Starter Projects .................................................................................................................. 5 Pinellas Alternative Analysis (AA) ....................................................................................................... 5 Lane Continuity Study ......................................................................................................................... 6 NEPA Process ..................................................................................................................................... 7 III Project Goals ....................................................................................................................................... 7 IV -

SEPTEMBER 2020 NEWSLETTER.Pub

SEPTEMBER 2020 webElect.net Your Campaign Connected ON THE MOVE ! OFFICIAL NEWSLETTER OF THE PINELLAS COUNTY REPUBLICAN EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE As we all revel in the positive aftermath of Pinellas County the Republican National Convention and Republican Executive are motivated by the vision of America as Committee Meeting portrayed there by ordinary men and women in extraordinary circumstances, it is now MONDAY, SEPTEMBER 14 time for us to redouble our commitment to keeping our government in responsible hands. 7 PM General Meeting We need to re-elect President Trump, but also need to provide him with elected officials ANNA PAULINA LUNA who will support his agenda. Just imagine Congressional Dist. 13 Candidate what he could have accomplished the past four years if he had not had to deal with the radical left and JULIE MARCUS “anonymous sources” assailing him at every turn. Pinellas County Supervisor of Elections & Candidate for Reelection We have a real opportunity to help the President by electing Anna Paulina Luna to Congress. Her opponent has voted with Nancy Feather Sound Country Club Pelosi and her radical left agenda more than 90% of the time. 2201 Feather Sound Drive, Clearwater 33762 The only way to remove Pelosi from power is to elect enough Republicans to the House. We have a real opportunity to do our (Social distancing and masks requested) part right here, right now. PCREC OFFICE HOURS I am especially calling on each of you to acquaint yourselves with the down ballot candidates and vote for the person who will 9 AM to 4 PM represent the conservative values of our Party. -

Sheriff Bob Gualtieri Pinellas County Sheriff's Office "Leading the Way for a Safer Pinellas"

Sheriff Bob Gualtieri Pinellas County Sheriff's Office "Leading The Way For A Safer Pinellas" January 25 , 2021 Chief Anthony Holloway St. Petersburg Police Department 1301 l51 Avenue North St. Petersburg, FL 33705 Dear Chief Holloway: The following are the results of the Pinellas County Use of Deadly Force Investigative Taskforce investigation regarding an officer-involved shooting by St. Petersburg Police Department (SPPD) officers on December 2, 2020 at approximately 4: 15 p.m. This is a redacted version of this letter that protects the identities of the undercover personnel pursuant to Chapter 119, F.S. On December 2n ct at approximately 4:30 p.m, SPPD notified the Pinellas County Sheriff's Office (PCSO) that an officer-involved shooting had just occurred at 1400 18th Avenue South. It was reported that a suspect (Dominque Harris (Harris)) shot and had attempted to murder a SPPD officer. The suspect was shot by return gunfire from six officers and was subsequently transported to a hospital and pronounced deceased. SPPD notified PCSO pursuant to the Pinellas County Use of Deadly Force Investigative Taskforce Agreement, and SPPD requested PCSO activate the Taskforce to conduct the required investigation. PCSO is the Supervising Agency for this investigation under the Taskforce Agreement, and as Sheriff, I am responsible for supervising the investigation and making determinations. I responded to the scene, conferred with Taskforce investigators, and have personally reviewed the evidence in this case, including forensic evidence, videos, photographs, and witness statements. The Taskforce assumed responsibility for the investigation after an on-scene briefing by SPPD commanders. Taskforce agencies participating in addition to PCSO were the Clearwater Police Department and the Pinellas Park Police Department. -

Florida Sting Operations Complaint

FLORIDA STING OPERATIONS COMPLAINT INTRODUCTION Since 2010, the state of Florida has arrested over 1200 men during highly publicized sting operations creating the illusion that law enforcement efforts to combat the issue of child solicitation justifies the millions in federal funding it has received. But the reality is that that is the farthest from the truth. In an effort to promote awareness and effectuate change, many of those who have been affected by Florida’s illegal sting operations are joining forces throughout the state to have their voices heard which is making a difference. This is a matter of great public importance. THE PROBLEM Law enforcement agencies are wrongfully subjecting men to the criminal justice system by using illegal tactics, violating federal law, misleading the public with false media reports, and using federal taxpayer dollars in the process. We understand the need to protect children, but these sting operations do little to do so due to the fact that men are not soliciting minors using adult oriented/dating sites. THE ICAC AND THE LAW Until recently, little was known about these ICAC sting operations conducted by various task forces throughout the state of Florida. In 2008, Congress passed the Protect the Children Act which essentially codified the authorization of the ICAC (see att #1). The purpose of the program is to help state and local law enforcement agencies develop an effective response to cyber enticement and child pornography cases. Under this program, regional ICAC task forces serve as sources of prevention, education and investigative expertise to provide assistance to parents, teachers, law enforcement and other professionals working on child victimization issues. -

September 14, 2016 2:00 PM

Pinellas County 315 Court Street, 5th Floor Assembly Room Clearwater, Florida 33756 Minutes - Final Wednesday, September 14, 2016 2:00 PM BCC Assembly Room Board of County Commissioners Charlie Justice, Chairman Janet C. Long, Vice-Chairman Dave Eggers Pat Gerard John Morroni Karen Williams Seel Kenneth T. Welch Board of County Commissioners Minutes - Final September 14, 2016 ROLL CALL - 2:03 P.M. Present: 6 - Charlie Justice, Janet C. Long, Dave Eggers, Pat Gerard, Karen Williams Seel, and Kenneth T. Welch Absent: 1 - John Morroni Others Present: James L. Bennett, County Attorney; Jewel White, Chief Assistant County Attorney (6:00 P.M.); Mark S. Woodard, County Administrator; Ken Burke, Clerk of the Circuit Court and Comptroller; Lynn Abbott, Board Reporter, Deputy Clerk; and Tony Fabrizio, Board Reporter. INVOCATION by Father Tom Morgan with St. Jerome Catholic Church in Largo PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE PRESENTATIONS AND AWARDS 1. Presentations and awards: Doing Things Employee Recognition - Roberto Quijada, Real Estate Management Patriot Day Proclamation Oldsmar Centennial Proclamation Hispanic Heritage Month Proclamation Doing Things Employee Recognition - Roberto Quijada, Real Estate Management Chairman Justice recognized Real Estate Management Craftworker Roberto Quijada for his dedication and can-do attitude and for building strong relationships with internal and external customers. He noted that Mr. Quijada is a 14-year employee who works at the County Justice Center maintaining its hundreds of doors and locks; whereupon, a video was shown highlighting the services Mr. Quijada provides. Patriot Day Proclamation Chairman Justice called forward Sunstar Paramedic and Assistant Supervisor Jared Sorenson, Pinellas County Sheriff’s Deputy Anthony Helstern, Treasure Island Fire Department Paramedic Joseph Manning, and Sheriff Bob Gualtieri. -

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT MIDDLE DISTRICT of FLORIDA TAMPA DIVISION PATRICIA HANNAH, As Plenary Legal Guardian of Darryl Va

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT MIDDLE DISTRICT OF FLORIDA TAMPA DIVISION PATRICIA HANNAH, as plenary legal guardian of Darryl Vaughn Hanna, Jr., an individual, Plaintiff, v. Case No. 8:19-cv-596-T-60SPF ARMOR CORRECTIONAL HEALTH SERVICES, INC., et al., Defendants. / ORDER Plaintiff served a notice for a Rule 30(b)(6) deposition by subpoena to each of three nonparty Sheriffs.1 The notices included between 22 to 24 areas of designations.2 This cause is now before the Court upon Sheriff Gualtieri’s Motion to Quash Nonparty Subpoena to Testify at a Deposition and for a Protective Order (Doc. 201), Sheriff Chronister’s Motion to Quash Nonparty Subpoena to Testify at a Deposition and for a Protective Order (Doc. 205), and nonparty Sheriff Staly’s Motion for Protective Order and Motion to Quash Subpoena Duces Tecum 3 (Doc. 220).4 The Court has considered the Sheriffs’ motions and the 1 Bob Gualtieri, in his official capacity as Sheriff of Pinellas County, Florida (Doc. 201-2); Chad Chronister, in his official capacity as Sheriff of Hillsborough County, Florida (Doc. 205- 2); and Rick Staly, in his official capacity as Sheriff of Flagler County, Florida (Doc. 220-1). 2 Plaintiff has subsequently withdrawn some of the areas of designations. 3 The Court notes that the subpoena to testify at a deposition served on Sheriff Staly does not seek production of documents or electronically stored information and, therefore, is not a subpoena duces tecum. See Doc. 220-1. 4 Sheriff Gualtieri, Sheriff Chronister, and Sheriff Staly will be collectively referred to as “the Sheriffs.” responses, replies, and other filings related thereto (Docs. -

2020 Annual Report

2020 ANNUAL REPORT FLORIDA SHERIFFS ASSOCIATION PROTECTING, LEADING & UNITING SINCE 1893 MISSION | THE MISSION OF THE FLORIDA SHERIFFS ASSOCIATION AS A SELF-SUSTAINING, CHARITABLE ORGANIZATION IS TO FOSTER THE EFFECTIVENESS OF THE OFFICE OF SHERIFF THROUGH LEADERSHIP, EDUCATION AND TRAINING, INNOVATIVE PRACTICES AND LEGISLATIVE INITIATIVES. CONTENTS STRATEGIC PLAN GOALS To provide effective and timely support, 2 OFFICERS & DIRECTORS training and information exchanges for 3 MEMBERSHIP Florida’s sheriffs 4 CHARITABLE PARTNERSHIP PROGRAMS To foster effective law enforcement, crime prevention, apprehension of 6 COMMUNICATING criminals and protection of life and OUR MISSION property of the citizens of Florida 9 FINANCIAL 10 TRAINING To promote public awareness about developments in law enforcement, 11 AWARDS & RECOGNITION crime prevention and public safety 12 SERVICE TO SHERIFFS To protect Florida’s future by promoting 17 CONFERENCES public support of programs and services 18 RESOURCES focused on youth of our state 19 GOVERNMENT AFFAIRS To effectively manage the resources of 20 COMMITTEES the Florida Sheriffs Association 21 ADMINISTRATIVE SERVICES & STAFF LETTER FROM THE EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR 1 DEAR MEMBER, I am pleased to present the 2020 Flor- To assist the sheriffs in meeting these challenges, FSA ida Sheriffs Association (FSA) Annual deployed a state-of-the-art online training system that al- Report. This has been a busy year for lowed sheriffs, deputies and all office personnel to obtain FSA, and we have achieved a great needed training in a safe environment. To help sheriffs’ deal on behalf of the sheriffs, their per- offices obtain needed personal protective equipment, sonnel, and the citizens of our state. FSA vetted more than 200 companies and thousands of The report will give more detail of the products when the gear was in short supply. -

WSUN—A Bright Spot in Our Radio History

FEBRUARY / 2018 ISSUE 59 Airmen & civilians at WSUN microphone. Identified are Louis Link, Glen Leland, W.E. WSUN—A Bright Spot in McEachern, Joe Frobole. Our Radio History circa 1943 A new AM radio station was created in July of 1927 when as what is now Route 60/Gulf-to-Bay Blvd., overlooking Tampa Bay, partners, the City and the St. Petersburg Chamber of Commerce are today on display in the Smithsonian Institute in Washington bought half ownership in a station owned by the Clearwater D.C. as they literally revolutionized AM radio engineering. Chamber of Commerce. St Pete’s half was named WSUN-AM, The dual WSUN/WFLA relationship lasted through decades which unofficially stood for “Why Stay Up North.” Clearwater’s of costly infighting between the St. Pete Chamber and the St. half became WFLA-AM. Pete City Manager, until 1941 when the City of St. Petersburg The sales agreement called for a crazy “shared” broadcast acquired “both halves.” WFLA moved to 940 kHz (and later to arrangement. WSUN and WFLA would each operate three nights today’s 970). WSUN stayed on the 620 frequency and began per week and alternating Sundays. Both stations used the same broadcasting full-time. transmitter and frequency, but had separate offices and studios. This was radio’s Golden Age…the early days before television. WSUN-AM began broadcasting on 590 kHz — with its own WSUN, as part of the NBC/Blue Network (later ABC), and aired identity—on November 1, 1927. The inaugural 4-hour broadcast The Adventures of Ozzie and Harriet, The Green Hornet, The from 7:30 -11:30 pm originated from their new $40,000 studios Lone Ranger, and Ted Mack’s Original Amateur Hour. -

Npmarch-April2015

Vol. 24 No. 2 The Independent Newspaper for Practitioners March/April 2015 $9.02 million proposed to settle APA practice assessment suit By James Bradshaw, Associate Editor APAPO, are not required to admit any www.PracticeAssessmentSettlement.co guilt in misleading members about the m that will be maintained by an inde- The American Psychological nature of the assessments, which were pendent settlement administrator, the Association (APA) and the APA Practice revealed to be “voluntary” in 2010, Portland, Ore., offices of Epig Class Being “Liked” on Facebook Organization (APAPO) are to pay $9.02 prompting the legal actions. Action Claims Solutions Inc. million under a proposed settlement to The agreement also calls for renam- See Page 20. end a class action suit filed by APA ing the assessment as “APAPO Continued on Page 3 practitioner members who contend they Membership Dues” with accompanying were deceived into thinking they had to wording on annual dues billings to Medicare penalties catch pay an additional “practice assessment” emphasize that APAPO membership is a to maintain APA membership. recommended option for practicing uninformed psychologists off guard The settlement must be approved by licensed psychologist members to sup- have been astounded by the number of the U.S. District Court for the District of port APAPO’s advocacy efforts but is By Paula E. Hartman-Stein, Ph.D. experienced psychologists who have been Columbia before any claims for payment not required to keep APA membership. unaware of PQRS, paying little attention may be submitted, but the plaintiffs’ An APA news release announcing Despite repeated announcements and to the changes going on in healthcare and acceptance of the terms makes approval the settlement in January quoted 2015 warnings from the Center for Medicare remaining in their silos until immediately likely forthcoming. -

March 6, 2018 the Honorable Rick Scott Governor, State of Florida the Capitol 400 S. Monroe Street Tallahassee, FL 32399-0001 Th

March 6, 2018 The Honorable Rick Scott The Honorable Joe Negron The Honorable Richard Corcoran Governor, State of Florida Senate President Speaker of the House The Capitol 409 The Capitol 420 The Capitol 400 S. Monroe Street 404 S. Monroe Street 402 S. Monroe Street Tallahassee, FL 32399-0001 Tallahassee, FL 32399-5229 Tallahassee, FL 32399-5000 Dear Governor Scott, President Negron, and Speaker Corcoran: Since last month’s tragic event at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School, sheriffs have been part of the statewide effort to bring forward solutions to keep our students safe. The welfare of our youth has always been a top priority for the sheriffs in Florida. We strongly believe both the House and Senate must pass comprehensive legislation this year to address a wide variety of school safety issues. Sheriffs fully support having all schools assigned a sworn sheriff’s deputy or police officer present on our school campuses. To achieve this end, sheriffs strongly believe the top priority must be additional state funding to ensure schools have a certified law enforcement officer ready to serve as a School Resource Officer (SRO). SRO programs emphasize the importance of collaboration between school officials and local law enforcement by promoting a community-based approach to school violence. Increasing the number of SROs on school campuses will greatly enhance school safety and protect students, teachers, and administrators. We are in the business of saving lives, and none are more precious than the lives of our children. We believe state funding for SROs is the best way to prevent another tragedy from occurring in our schools.