Doing Ethnography in Urban Spaces Author(S): Vidyapogu Pullanna Source: Explorations, ISS E-Journal, Vol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

District Census Handbook, Hyderabad, Part XIII a & B, Series-2

CENSUS OF INDIA 1981 SERIES 2 ANDHRA PRADESH DISTRICT CENSUS. HANDBOOK HYDERABAD PARTS XIII-A & B VILLAGE & TOWN DIRECTORY VILLAGE & TOWNWISE PRIMARY CENSUS ABSTRACT S. S. JAYA RAO OF THE INDIAN ADMINISTRATIVE SERVICE DIRECTOR OF CENSUS OPERATIONS ANDHRA PRADESH PUBLISHED BY THE GOVERNMENT OF ANDHRA PRADESH 1987 ANDHRA PRADESH LEGISLATURE BUILDING The motif presented on the cover page represents the new Legislature building of Andhra Pradesh State located in the heart of the capital city of Hyderabad. August, 3rd, 1985 is a land mark in the annals of the Legislature of Anohra Pradesh on which day the Prime Minister, Sri Rajiv Gandhi inaugu rated the Andhra Pradesh Legislacure Build ings. The newly constructed Assembly Build ing of Andhra Pradesh is located in a place adorned by thick vegitation pervading with peaceful atmosphere with all its scenic beauty. It acquires new dimensions of beauty, elegance and modernity with its gorgeous and splen did constructions, arches, designs, pillars of various dImensions, domes etc. Foundation stone for this new Legislature Building was laid by the then Chief Minister, Dr. M. Chenna Reddy on 19th March, 1980. The archilecture adopted for the exterior devation to the new building is the same as that of the old building, leaving no scope for differentiation between the two building~. The provision of detached round long columns under the arches add more beauty to the building. The building contains modern amenities such as air-connitioning, interior decoration and reinforced sound system. There is a provision for the use of modc:rn sophisticated electronic equipment for providing audio-system. -

Government of Andhra Pradesh

GOVERNMENT OF TELANGANA (Police Department) Office of the Commissioner of Police, Hyderabad City. No.Tr.T4/1212/2021 Date:13-08-2021 TRAFFIC AND PARKING ARRANGEMENTS IN CONNECTION WITH THE INDEPENDENCE DAY-2021 CELEBRATIONS ON 15-08-2021 AT RANI MAHAL LAWNS, GOLCONDA FORT, HYDERABAD. In exercise of the powers conferred upon me under section 21(1) (b) of Hyderabad City Police Act, I, Anjani Kumar, IPS, Commissioner of Police, Hyderabad City do hereby notify for the information of the general public that in order to facilitate proper regulation of traffic in connection with the Independence Day- 2021 Celebrations at Rani Mahal Lawns, Golconda Fort, Hyderabad on 15th August 2021 at 10.00 AM., the following traffic restrictions will be enforced. 1. The road from Ramdevguda to Golconda Fort will be closed for general vehicular traffic from 7.00 AM to 12.00 Noon on 15th August 2021. 2. The entry from Ramdevguda to Golconda Fort will be used for the A, B & C car pass holders who are invited to attend Independence Day Celebrations - 2021 including Flag hosting ceremony from 7.30 AM to 11.00 AM on 15th August 2021. 3. All the invitees coming on vehicles with A, B & C car Passes from Sec'bad, Banjara Hills, Masab Tank, Mehdipatnam side are requested to come via: Rethi Bowli & Nanal Nagar Junctions and take left turn towards Balika Bhavan, Langar House Flyover, Tippu Khan Bridge, Ramdevguda junction right turn Makai Darwaza and Golconda Fort Gate for alighting. After alighting I) “A” Car pass holder should park their vehicles on the main road in front of the Fort main Gate i.e. -

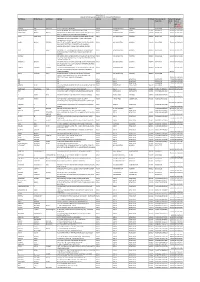

First Name Middle Name Last Name Address Country State

Biocon Limited Amount of unclimed and unpaid Interim dividend for FY 2010-11 First Name Middle Name Last Name Address Country State District PINCode Folio Number of Amount Proposed Securities Due(in Date of Rs.) transfer to IEPF (DD- MON-YYYY) JAGDISH DAS SHAH HUF CK 19/17 CHOWK VARANASI INDIA UTTAR PRADESH VARANASI BIO040743 150.00 03-JUN-2018 RADHESHYAM JUJU 8 A RATAN MAHAL APTS GHOD DOD ROAD SURAT INDIA GUJARAT SURAT 395001 BIO054721 150.00 03-JUN-2018 DAMAYANTI BHARAT BHATIA BNP PARIBASIAS OPERATIONS AKRUTI SOFTECH PARK ROAD INDIA MAHARASHTRA MUMBAI 400093 BIO001163 150.00 03-JUN-2018 NO 21 C CROSS ROAD MIDC ANDHERI E MUMBAI JYOTI SINGHANIA CO G.SUBRAHMANYAM, HEAD CAP MAR SER IDBI BANK LTD, INDIA MAHARASHTRA MUMBAI 400093 BIO011395 150.00 03-JUN-2018 ELEMACH BLDG PLOT 82.83 ROAD 7 STREET NO 15 MIDC, ANDHERI EAST, MUMBAI GOKUL MANOJ SEKSARIA IDBI LTD HEAD CAPITAL MARKET SERVIC CPU PLOT NO82/83 INDIA MAHARASHTRA MUMBAI 400093 BIO017966 150.00 03-JUN-2018 ROAD NO 7 STREET NO 15 OPP SPECIALITY RANBAXY LABORATORI ES MIDC ANDHERI (E) MUMBAI-4000093 DILIP P SHAH IDBI BANK, C.O. G.SUBRAHMANYAM HEAD CAP MARK SERV INDIA MAHARASHTRA MUMBAI 400093 BIO022473 150.00 03-JUN-2018 PLOT 82/83 ROAD 7 STREET NO 15 MIDC, ANDHERI.EAST, MUMBAI SURAKA IDBI BANK LTD C/O G SUBRAMANYAM HEAD CAPITAL MKT SER INDIA MAHARASHTRA MUMBAI 400093 BIO043568 150.00 03-JUN-2018 C P U PLOT NO 82/83 ROAD NO 7 ST NO 15 OPP RAMBAXY LAB ANDHERI MUMBAI (E) RAMANUJ MISHRA IDBI BANK LTD C/O G SUBRAHMANYAM HEAD CAP MARK SERV INDIA MAHARASHTRA MUMBAI 400093 BIO047663 150.00 03-JUN-2018 -

District Census Handbook, Hyderabad, Part II

CENSUS OF INDIA, 1951 HYDERABAD STATE District Cel1sus Hal1dbook HYDERABAD DISTRICT PART II Issued by BUREAU OF ECONOMICS AND STATISTICS FINANCE DEPARTMENT GOVERNMENT OF HYDERABAD PRICE Rs. 4 HYDERABAD DISTRICT HYDERABAD DISTRICT HYDERABAD STATE SCALE 1 INCH-1S MILES "'+. 0-;, "'.,:f>,r • 'f'", I v"'/ IrfEDAK DISTRICT. J fROM SANGAREOOY ;f:_._._ • '''1 FROM WADI ~:;nU~~~~~ TO KAZIPET fROM PAR(H ",., ,.,., NALGONDA DISTRICT i l........ J" .1 '-.: ...... ," ..... "" )" MAHBUSNAGAR DISTRICT '.-.• ~ ....0 '. c....... " "'.,.'f-Q ~ '1 REFERENOES DISTRICT BOUNDARY _ •• _ •• _ .. _ TALUQ .f '" " DISTRICT HEADQUARTER (3) TALUQ ... " o ~OAD RAILWAY M. G. 4"" ... " ......... ~IV~.R R,,'LWAY 8. G.. P .. '::PAREI) By THE SETTLEMENT & LAND RECORD DEPT CON'tENTS PAGE' MAP OF HYDERABAD DISTRICT Frontispiece PT,jllCt' v l!:xplanatory Note on Tables .. 1 I,ist of Censlls Tracts~H.'·derabad District 5 1.' ,GENERAL POPULATION TABLES Table A- I--Area, Houses and Population .. 6 Table A- I1--Variation in Population during Fifty Years 8 Table A- III~Towns and Villages Classified by Population 10 Table A- IV-Towns Classified by Population with Variations since 1901 12 Table A- V~Towns arranged Territorially with Population by I,ivelihood Classes 16 ,. 2. ECONOMIC TABLES Table B- I-Livelihood Classes and Sub-Classes .. 18 Table B- I1~Secondary Means of Livelihood .. 24 3. SOCIAL AND CULTURAL TABLES Table D-I (i) Languages-Mother Tongue 28 Table D-I (ii) Languages-Bilingualism 82 Table D- II-Religion .. 40 Table D- III--Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes 42 Tahle D-VII--Htl:'racy by Educational Standards 44 4. GENERAL SUMMARY TABLE Table E Summary Figures by Tahsils 46 5. -

Aditya Empress Towers

https://www.propertywala.com/aditya-empress-towers-hyderabad Aditya Empress Towers - Shaikpet, Hyderabad Combining luxury and high quality Aditya Empress Towers by Aditya Constructions at Aziz Bagh Colony, Shaikpet in Hyderabad offers residential project that host 3bhk apartments in various sizes. Project ID: J396232118 Builder: Aditya Constructions Location: Aditya Empress Towers,Aziz Bagh Colony, Shaikpet, Hyderabad (Telangana) Completion Date: Jul, 2020 Status: Started Description Aditya Empress Towers is an iconic project combining luxury and high quality in Aziz Bagh Colony, Shaikpet offers 3 bhk spacious apartment in the size ranges between 1575 to 2380 sqft. The project provides amenities like beautifully designed clubhouse and the swimming pool give it a rich ambience and allows you to pamper yourself. Jubilee Hills area is strategically located to meet the needs of the people who are constantly on the move. It has excellent connectivity to all parts of the city and is close to the international airport. Amenities : Power backup Intercom Vastu Club house Gated community Gym Health facilities Indoor games Landscaped garden Lift Maintenance staff Meditation hall Play area Pucca road Security personnel Swimming pool Incepted in the year 2002, Aditya Construction Company is a reputed name in the real estate market of Hyderabad. It has developed residential projects backed by innovative features and technology. Aditya Construction Company is a recipient of awards; including Luxury Villa Project 2015 for its Villa Grande Luxury Apartment Project 2015 for its Empress Towers organized by Siliconindia Real Estate Awards, to name a few. The company strives to be one of the best property developers by building world class homes that offer value for the money invested by the customers. -

Slno Folio No. Name Address Pin Code Amount Due(Rs.) Warrant No Due Date for IEPF

MAHINDRA & MAHINDRA FINANCIAL SERVICES LTD Statement showing unpaid/unclaimed dividend as on 31/10/2019 for the dividend year FINAL 2012-2013 Slno Folio No. Name Address Pin Code Amount Warrant No Due Date for IEPF Due(Rs.) 1 MMF0000071 HIMANAGAJA ANUMAKONDA 3/188, NAWABPET, NELLORE 524002 32994.00 900093 26-JUL-2020 2 MMF0000075 SREENIVASA RAO AILNENI C/O. PANCHSHEEL ENTERPRISES, 505002 56250.00 900092 26-JUL-2020 RAMPOOR, HYDERABAD ROAD, KARIMNAGAR 3 MMF0000078 VIMALA DEVI SOGANI C/O. ENGINEERING SALES CORPN., 302001 90000.00 900046 26-JUL-2020 SOGANI BHAVAN, M.I. ROAD, JAIPUR 4 MMF0000107 PARUL JAIN M/s. JAIN BROTHERS, STATION ROAD, 246746 45000.00 900037 26-JUL-2020 P.O. SEOHARA, BUJNOR 5 MMF0000133 UDAY S. KOTAK 36-38A, NARIMAN BHAVAN, 227 400021 360.00 900212 26-JUL-2020 NARIMAN POINT, BOMBAY 6 MMF0000136 NAGRAJ SITARAM IYENGAR A/22, VISHNUBAUG, 137, S.V. ROAD 400058 2394.00 900202 26-JUL-2020 ANDHERI (WEST), BOMBAY 7 MMF0000171 P. V. RAGHUNATH PLOT NO. 34, ABILASHA PEARL GARDEN 560062 450.00 900253 26-JUL-2020 OFF KARAKAPURA RD, VAJARSHALLI TALEGETHAPURA PORT BANGALORE 8 MMF0000392 DILIP K. MULCHANDANI C/O. KRISHNA MURARI GUPTA 831009 18000.00 900101 26-JUL-2020 SITARANDERA NEW LAYOUT P.O. AGRICO JAMSHEDPUR JAMSHEDPUR 9 MMF0000393 SURJIT SINGH B/7, SECTOR - B, POCKET-7 HOUSE NO. 0 4500.00 900251 26-JUL-2020 5003 2ND FLOOR, VASANT KUNJ NEW DELHI 10 MMF0000395 PRAVIN J. PARAB FLAT NO 504 XENO SUMMIT JAIHIND 500081 9000.00 900073 26-JUL-2020 ENCLAVE, JAI HIND GANDHI ROAD MADHAPUR K V RANGAREDDY, TELANGANA 11 MMF0000398 PREET INDER SINGH E1/31, AREA COLONY BHOPAL 0 4500.00 900190 26-JUL-2020 12 MMF0000416 B.J. -

Route Bus Point Pickup Drop Gb 01 Andhra Bank Begumpet

MASTER REGULAR ROUTES 2019-2020 ROUTE BUS POINT PICKUP DROP GB 01 ANDHRA BANK BEGUMPET AIRPORT 7:00 AM 3:55 PM GB 01 LIFE STYLE BEGUMPET 7:05 AM 3:45 PM GB 01 TIMES OF INDIA RD.1 BANJARA HILLS 7:10 AM 3:35 PM GB 01 DMART, OPP. MADHAPUR PS 7:15 AM 3:30 PM GB 01 KARACHI BAKERY MADHAPUR 7:21 AM 3:25 PM GB 01 RATNADEEP HITECH CITY MADHAPUR 7:25 AM 3:21 PM GB 01 MY HOME NAVADWEEPA HITECH 7:26 AM 3:20 PM GB 01 VLCC NR JAYABHERI SILICON KOTHAGUDA 7:28 AM 3:16 PM GB 01 PRESTIGE IVY LEAGUE, KOTHAGUDA 7:30 AM 3:15 PM GB 01 RATNADEEP BP RAJU MARG KOTHAGUDA 7:31 AM 3:05 PM GB 01 GOVT. SCHOOL MASJIDBANDA 7:40 AM 2:55 PM GB 01 PAVANI AQUA MASJIDBANDA 7:41 AM 2:55 PM GB 01 CYBER MEADOWS MASJIDBANDA 7:42 AM 2:56 PM GB 01 XENOPEARL APARTMENTS MASJIDBANDA 7:45 AM 2:55 PM GB 01 RELIANCE PARADISE MASJIDBANDA 7:46 AM 2:51 PM GB 01 RELIANCE PARADISE T JUNCTION 7:50 AM 2:51 PM ROUTE BUS POINT PICKUP DROP GB 02 GOVT NURSING COLLEGE RAJBHAVAN 7:00 AM 4:00 PM GB 02 MORE MEGASTORE, ERRAMANZIL 7:10 AM 3:50 PM GB 02 G V K MALL RD.1 BANJARA HILLS 7:13 AM 3:42 PM GB 02 RATNADEEP SUPERMARKET, ROAD NO.7, BANJARA HILLS 7:15 AM 3:40 PM GB 02 BANJARA HILLS ROAD NO 10 MASQUATI DAIRY PRODUCTS 7:18 AM 3:35 PM GB 02 INNER SPACE FURNITURES RD.12 BANJARA HILLS 7:25 AM 3:20 PM GB 02 L & T TOWNSHIP CLUB HOUSE 7:35 AM 3:00 PM GB 02 TELECOMNAGAR GATE NR L&T 7:40 AM 2:55 PM GB 02 TELECOMNAGAR(P) PINEVALLEY(D) GB 02 NA 2:55 PM GB 02 GREEN BAWARCHI, INDIRANAGAR 7:42 AM 2:52 PM GB 02 PARADISE TAKE AWAY GACHIBOWLI 7:45 AM 2:50 PM ROUTE BUS POINT PICKUP DROP GB 03 PILLER NO 125 NR SPENCERS ATTAPUR 7:00 AM 3:55 PM GB 03 GUDIMALKAPUR X ROADS. -

Athena, Mundane Is an Outdated Word

There’s value. And there’s value enhanced. There’s a future. And there’s a future more rewarding. There’s life. And there’s life appreciated. A D I T Y A AT H E N A @ O.U. C O LO N Y, S H A I K P E T TS RERA No: P02400001111 A D I T Y A Life Beyond Compromises AT H E N A Yes, at Aditya Athena, mundane is an outdated word. Stereotypical layout is a thing of past, small cramped matchbox spaces are thrown out of dictionary, and a splurge of amenities, in a cozy comfort of a gated community, with a proven stamp of Aditya quality takes over. As in each dream of yours, we believe in living it real. A D I T Y A Life Beyond Compromises AT H E N A Yes, at Aditya Athena, mundane is an outdated word. Stereotypical layout is a thing of past, small cramped matchbox spaces are thrown out of dictionary, and a splurge of amenities, in a cozy comfort of a gated community, with a proven stamp of Aditya quality takes over. As in each dream of yours, we believe in living it real. A D I T Y A Welcome to a brighter, happier world that is being brought to you in Hyderabad’s most high-potential area -Khajaguda. Welcome to laughter, AT H E N A forever. Rising as a premium gated residential cluster of six uber stylish towers spread over an intelligently landscaped layout in 6 Acres, 2.71 Guntas, Today’s Marvel & Tomorrow’s Classic. -

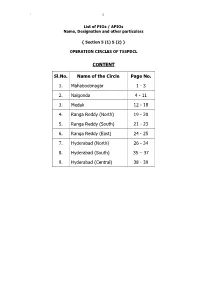

Name, Designation and Other Particulars of Public Information Officers

` 0 List of PIOs / APIOs Name, Designation and other particulars { Section 5 (1) 5 (2) } OPERATION CIRCLES OF TSSPDCL CONTENT Sl.No. Name of the Circle Page No. 1. Mahaboobnagar 1 - 3 2. Nalgonda 4 - 11 3. Medak 12 - 18 4. Ranga Reddy (North) 19 - 20 5. Ranga Reddy (South) 21 - 23 6. Ranga Reddy (East) 24 - 25 7. Hyderabad (North) 26 - 34 8. Hyderabad (South) 35 – 37 9. Hyderabad (Central) 38 - 39 ` 1 Name, Designation and other Particulars of Public Information Officers { Section 5 (1) 5 (2) } Mahaboobnagar Circle Sl. Name of the office Name of the PIO and Cell No. Name of the APIO and Cell No. No. District office Circle / Sri N.S.R.Murthy, DE/Technical,,Cell:9440813415, Sri B. Manikyalu, ADE/Tech., 1 Mahaboobnagar 08542-272946-272714,Fax 08542 - 272798 ,cell:9440813415, 08542-272730 G.Sudha Rani AE/Tech/D.O./MBNR,, 2 Division /Mahaboobnagar Venkataiah, DE/OP/MAHABUBNAGAR,, 9440813418 08542-273138 Sub-division, Sureshkumar, Sub-Er/MBNR(TOW),, 3 Srinivasa Chary, ADE/OP/MBNR(TOWN).,, 9440813431 Mahaboobnagar 08503-272926 Shanthi , Sub-Er./OP/TOWN-1, 4 Section Town-I/MBNR B.Ramesh Babu, AE/OP/TOWN-1,, 9440813457 08542-241666 Vacant, Sub-Er./OP/TOWN-2, 5 Section Town-II/MBNR Satyanna, AE/OP/TOWN-2,, 9491066205 08542-243666 6 Section /Town-III/MBNR M.Srinivas, AE/OP/TOWN-3,, 9440813459 K.Venkatesh/ Town-3,, 08542-243555 Ramakrishna, Sub-Er/MBNR(RURAL),, 7 Sub-division,MBNR Rural B.Srinivasulu, ADE/OP/MBNR(RURAL),, 9440813444 08542-273146 Chandra Shekar sub-eng I/C AE/OP/C&O/MBNR,, Chandra shekar sub-Er (I/C), 8 C&O/Section/MBNR 9440813890 Sub-Engineer, 9 Section/Koilkonda B. -

Unit Selection to Improve Naturalness in Speech Synthesis

International Journal of Applied Engineering Research ISSN 0973-4562 Volume 13, Number 21 (2018) pp. 15011-15015 © Research India Publications. http://www.ripublication.com Unit Selection to Improve Naturalness in Speech Synthesis Dr. K.V.N.Sunitha1 P. Sunitha Devi2 1Principal, BVRIT College of Engineering for women, Bachupally, Hyderabad, Telangana, India. 2Assistant Professor, Computer Science and Engineering Department, G.Narayanamma Institute of Technology & Science, Shaikpet, Hyderabad, Telangana, India. Abstract tagging, letter-to-sound rules, syllabification, stress-patterns in one form or the other to build a text processing component of Speech synthesis is a process that can generate human-like a TTS system. However for minority languages (which are not speech for any text input to imitate human speakers. The well researched or do not have enough linguistic resources), it objective of a text to speech system is to convert an arbitrary involves several complexities starting from accumulation of text into its corresponding speech. Generating speech that is text corpora in digital and processable format. Linguistic close to natural human speech is always a challenging issue components are not available in such rich fashion for all for synthesis systems. Naturalness depends on the kind of languages of the world. In practical world, minority languages available database, and the algorithms that choose the including some of the Indian languages do not have that appropriate speech units from the database. The issue lies on luxury of assuming some or any of the linguistic components. what should be the unit of speech to be stored in database. This paper projects the work carried out in identifying most appropriate speech unit towards improving naturalness. -

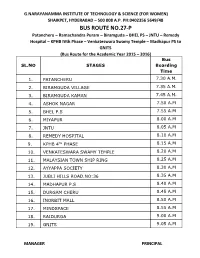

Bus Route No.27-P

G.NARAYANAMMA INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY & SCIENCE (FOR WOMEN) SHAIKPET, HYDERABAD – 500 008 A.P. PH:0402356 5649/48 BUS ROUTE NO.27-P Patancheru – Ramachandra Puram – Biramguda – BHEL PS – JNTU – Remedy Hospital – KPHB IVth Phase – Venkateswara Swamy Temple – Madhapur PS to GNITS (Bus Route for the Academic Year 2015 – 2016) Bus SL.NO STAGES Boarding Time 1. PATANCHERU 7.30 A.M. 2. BIRAMGUDA VILLAGE 7.35 A.M. 3. BIRAMGUDA KAMAN 7.45 A.M. 4. ASHOK NAGAR 7.50 A.M 5. BHEL P.S 7.55 A.M 6. MIYAPUR 8.00 A.M 7. JNTU 8.05 A.M 8. REMEDY HOSPITAL 8.10 A.M TH 9. KPHB 4 PHASE 8.15 A.M 10. VENKATESWARA SWAMY TEMPLE 8.20 A.M 11. MALAYSIAN TOWN SHIP RING 8.25 A.M 12. AYYAPPA SOCIETY 8.30 A.M 13. JUBLI HILLS ROAD.NO:36 8.35 A.M 14. MADHAPUR P.S 8.40 A.M 15. DURGAM CHERU 8.45 A.M 16. INORBIT MALL 8.50 A.M 17. MINDSPACE 8.55 A.M 18. RAIDURGA 9.00 A.M 19. GNITS 9.05 A.M MANAGER PRINCIPAL G.NARAYANAMMA INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY & SCIENCE (FOR WOMEN) AUTONOMOUS SHAIKPET, HYDERABAD – 500 008 A.P. PH:0402356 5649/48 BUS ROUTE NO.1-D Hayatnagar – Vanasthalipuram – Vishnu Theatre – Kothapet – Dilshukhnagar – Chaderghat – Kachiguda to GNITS (Bus Route for the Academic Year 2013 – 2014) Bus SL.NO STAGES Boarding Time 1. HAYATH NAGAR 7.25 A.M. 2. HIGH COURT COLONY 7.30 A.M. 3. VANASTHALIPURAM (GANESH TEMPLE) 7.32 A.M. -

D.No.5-3-682,Shop No.4,Vijayapuri Colony Phase-1,Vana

S.NO City STORE NAME ADDRESS VIJAYAPURI 1 Hyderabad COLONY(VANASTALIPURAM) D.No.5-3-682,Shop No.4,Vijayapuri Colony Phase-1,Vanasthalipuram,Ranga Reddy Dist-500070 D.No.5-5-148/4 &5-5-148/5,Beside Heritage Supermarket,Vanasthali Hills,Saheb Nagar,Ranga 2 Hyderabad VANASTHALI HILLS Reddy (DT)500070 . 3 Hyderabad VANASTHALIPURAM DR NO-6-2-688,PHASE2 LIG VANASTHALIPURAM SAHEB NAGAR KALAN RR DISTS 500070 4 Hyderabad B.N.REDDY-VANASTHALIPURAM H.No.Type-II-30, Shop No.1&2, Self Finance Colony, Vanasthalipuram, Hyderabad-70. GANESH TEMPLE- 5 Hyderabad VANASTHALIPURAM D.No: 6-2-689,Near: Ganesh Temple Road, Phase -II, Vanasthalipuram, Haythnagar(m) R.R.Dist 6 ROAP MAHABOOBNAGAR 1-5-35/6, New Town, Mahaboob Nagar, Mahaboob Nagar Dist. METTUGUDA - 7 ROAP MAHABOOBANAGAR - 2 H.No.1-4-30/D/B, Mettuguda, Opp.Govt.Hospitals, Mahaboobnagar. 8 ROAP KALWAKURTHY 6-20/4, Opp SBI Kalwakurthy, Mahaboob Nagar 9 ROAP ACHAMPET H-NO:4-186,MAIN ROAD, NEAR POST OFFICE, ACHAMPET, MAHABOOBNAGAR DIST. 509375. 10 ROAP JADCHERLA D.No.16-4,Netaji Road,Badepally (Village), Jadcherla(MA),Mahabub Nagar Dist-509304 NARAYANAPET D.No.1-6-86, Main Road, Near Old Busstand, Narayanpet (Post & Mandal), Mahaboob Nagar Dist 11 ROAP (MAHABOOBNAGAR) - 509210 VENKATESHWARA COLONY 12 ROAP (MAHABUB NAGAR ) D.No.7-4-58/A,Venkateshwar Colony,Main Road Opp:A.P.S.E.B.Buliding,Mahabub D NO : 2-99,PADMAVATHI COLONY, SHADNAGAR, FAROOQ NAGAR, 13 ROAP SHADNAGAR MAHABOOBNAGAR,TELANGANA, AP 14 ROAP KOTHUR D.NO.1-46,PENJARLA ROAD, OPP .S.B.H, KOTHUR, MAHBOOB NAGAR DIST-509338(AP) 15 ROAP CLOCK TOWER,MBNR D-NO.2-6-94/2,MARKET ROAD, CLOCK TOWER, MAHABUB NAGAR 16 ROAP NEW TOWN,MBNR D.No.1-5-69/1B, NEW TOWN, MAHABOOB NAGAR DIST VENKATESWARACOLONY, 17 ROAP MBNR H.No.7-5-108 & 7-5-109, Venkateswara Colony, Mahaboob Nagar .