MW-Rbm-Annual Report-2016.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rivers Monitoring and Evaluation Plan V1.0 2020

i Rivers Monitoring and Evaluation Plan V1.0 2020 Contents Acknowledgement to Country ................................................................................................ 1 Contributors ........................................................................................................................... 1 Abbreviations and acronyms .................................................................................................. 2 Introduction ........................................................................................................................... 3 Background and context ........................................................................................................ 3 About the Rivers MEP ............................................................................................................. 7 Part A: PERFORMANCE OBJECTIVES ..................................................................................... 18 Habitat ................................................................................................................................. 24 Vegetation ............................................................................................................................ 29 Engaged communities .......................................................................................................... 45 Community places ................................................................................................................ 54 Water for the environment .................................................................................................. -

The Future of the Yarra

the future of the Yarra ProPosals for a Yarra river Protection act the future of the Yarra A about environmental Justice australia environmental Justice australia (formerly the environment Defenders office, Victoria) is a not-for-profit public interest legal practice. funded by donations and independent of government and corporate funding, our legal team combines a passion for justice with technical expertise and a practical understanding of the legal system to protect our environment. We act as advisers and legal representatives to the environment movement, pursuing court cases to protect our shared environment. We work with community-based environment groups, regional and state environmental organisations, and larger environmental NGos. We also provide strategic and legal support to their campaigns to address climate change, protect nature and defend the rights of communities to a healthy environment. While we seek to give the community a powerful voice in court, we also recognise that court cases alone will not be enough. that’s why we campaign to improve our legal system. We defend existing, hard-won environmental protections from attack. at the same time, we pursue new and innovative solutions to fill the gaps and fix the failures in our legal system to clear a path for a more just and sustainable world. envirojustice.org.au about the Yarra riverkeePer association The Yarra Riverkeeper Association is the voice of the River. Over the past ten years we have established ourselves as the credible community advocate for the Yarra. We tell the river’s story, highlighting its wonders and its challenges. We monitor its health and activities affecting it. -

Maroondah Water Supply System (Upper and Central Sections) H2381

HERITAGE COUNCIL DETERMINATION Determination Date 7 December 2017 Place/Object Name Maroondah Water Supply System (Upper and Central Sections) Location Healesville, Yarra Glen, Christmas Hills, Greensborough VHR Number H2381 Place Category Heritage Place At a meeting of the Heritage Council on 7 December 2017 it was determined to include the above place in the Victorian Heritage Register and make certain amendments to the registration material that had been proposed in the Executive Director’s Recommendation, namely amendments to the Statement of Cultural Heritage Significance and to the description of the Extent of Registration for the Place as compared with what had been proposed by the Executive Director. The Heritage Council endorses the attached registration information for the above place. Professor Stuart Macintyre AO Chair, Heritage Council of Victoria Page | 1 Recommendation of the Executive Director and assessment of cultural heritage significance under s.32 of the Heritage Act 1995 Place: Maroondah Water Supply System (Upper and Central Sections) Location: Healesville, Yarra Glen, Christmas Hills, Greensborough VHR Number: H2381 Category: Heritage Place Hermes Number: 197552 Heritage Overlays: Yarra Ranges Shire HO141: Former township of Fernshaw HO156: Badger Creek Weir and Park HO173: Grace Burn Weir and Aqueduct HO174: Maroondah Catchment, Reservoir & Park HO177: Donnelly's Creek Weir, Condon’s Gully HO178: Mt Juliet Cairn Nillumbik Shire HO2: Maroondah Aqueduct; Entire Length (within Nillumbik) at various sites from Skyline Road, Christmas Hills to Allendale Road, Diamond Creek HO56: Maroondah aqueduct pipe track 23 Whittlesea Shire HO89: Maroondah Aqueduct over Plenty River Bridge Other listings: National Trust: Black Spur, Maroondah Highway EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR RECOMMENDATION TO THE HERITAGE COUNCIL: Recommendation That the Maroondah Water Supply System (Upper and Central Sections) be included as a Heritage Place in the Victorian Heritage Register under the Heritage Act 1995 [Section 32 (1)(a)]. -

Regional Bird Monitoring Annual Report 2018-2019

BirdLife Australia BirdLife Australia (Royal Australasian Ornithologists Union) was founded in 1901 and works to conserve native birds and biological diversity in Australasia and Antarctica, through the study and management of birds and their habitats, and the education and involvement of the community. BirdLife Australia produces a range of publications, including Emu, a quarterly scientific journal; Wingspan, a quarterly magazine for all members; Conservation Statements; BirdLife Australia Monographs; the BirdLife Australia Report series; and the Handbook of Australian, New Zealand and Antarctic Birds. It also maintains a comprehensive ornithological library and several scientific databases covering bird distribution and biology. Membership of BirdLife Australia is open to anyone interested in birds and their habitats, and concerned about the future of our avifauna. For further information about membership, subscriptions and database access, contact BirdLife Australia 60 Leicester Street, Suite 2-05 Carlton VIC 3053 Australia Tel: (Australia): (03) 9347 0757 Fax: (03) 9347 9323 (Overseas): +613 9347 0757 Fax: +613 9347 9323 E-mail: [email protected] Recommended citation: BirdLife Australia (2020). Melbourne Water Regional Bird Monitoring Project. Annual Report 2018-19. Unpublished report prepared by D.G. Quin, B. Clarke-Wood, C. Purnell, A. Silcocks and K. Herman for Melbourne Water by (BirdLife Australia, Carlton) This report was prepared by BirdLife Australia under contract to Melbourne Water. Disclaimers This publication may be of assistance to you and every effort has been undertaken to ensure that the information presented within is accurate. BirdLife Australia does not guarantee that the publication is without flaw of any kind or is wholly appropriate for your particular purposes and therefore disclaims all liability for any error, loss or other consequence that may arise from you relying on any information in this publication. -

Central Region

Section 3 Central Region 49 3.1 Central Region overview .................................................................................................... 51 3.2 Yarra system ....................................................................................................................... 53 3.3 Tarago system .................................................................................................................... 58 3.4 Maribyrnong system .......................................................................................................... 62 3.5 Werribee system ................................................................................................................. 66 3.6 Moorabool system .............................................................................................................. 72 3.7 Barwon system ................................................................................................................... 77 3.7.1 Upper Barwon River ............................................................................................... 77 3.7.2 Lower Barwon wetlands ........................................................................................ 77 50 3.1 Central Region overview 3.1 Central Region overview There are six systems that can receive environmental water in the Central Region: the Yarra and Tarago systems in the east and the Werribee, Maribyrnong, Moorabool and Barwon systems in the west. The landscape Community considerations The Yarra River flows west from the Yarra Ranges -

Sites of (Biological) Significance Review

MANNINGHAM BIOSITES MANNINGHAM CITY COUNCIL SITES OF (BIOLOGICAL) SIGNIFICANCE REVIEW Report by Paul Foreman Economic and Environmental Planning Unit, Manningham City Council With chapters on Bryophytes by David Meagher of Zymurgy Consultants and Invertebrates by Alan Yen and John Wainer of the Department of Primary Industries November 2004 Front Cover: Fringed Helmet Orchid (Corysanthes fimbriata). “an uncommon species of sparadic distribution in Victoria” (Backhouse and Jeans 1995). Listed as rare on the Victorian Rare or Threatened species list. Recorded from one Manningham biosite. Image supplied by Justin Welander Table of Contents PREFACE .....................................................................................................................1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ..........................................................................................................2 ABBREVIATIONS .....................................................................................................................3 SUMMARY .....................................................................................................................4 1 BACKGROUND ...............................................................................................................6 1.1 Introduction...................................................................................................................... 6 1.2 Study aim......................................................................................................................... 6 1.3 -

2019-20 Annual Stream Flow Management Plan Report

2020-21 Annual Stream Flow Management Plan Report Annual report for Melbourne Waters Stream Flow Management Plans (SFMP’s): Hoddles Creek, Little Yarra and Don Rivers, Olinda Creek, Plenty River, Steels, Pauls and Dixons Creeks, Stringybark Creek, Woori Yallock Creek. September 2021 Melbourne Water is owned by the Victorian Government. We manage Melbourne’s water supply catchments, remove and treat most of Melbourne’s sewage, and manage rivers and creeks and major drainage systems throughout the Port Phillip and Westernport region. Forward Melbourne Water is pleased to present the amalgamated Annual Report for the Hoddles Creek, Little Yarra and Don Rivers, Olinda Creek, Plenty River, Steels, Pauls and Dixons Creeks, Stringybark Creek, and Woori Yallock Creek Water Supply Protection Area Stream Flow Management Plans (the Plans) for the 2020-21 water year. Melbourne Water is responsible for the implementation, administration and enforcement of the Plans which were approved by the Minister administering the Water Act 1989 (Vic). This report has been prepared and submitted to the Minister for Water in accordance with section 32C of the Water Act 1989 (Vic). This report provides an overview of the surface water management activities administered under each Plan during the 2020/21 water year. A copy of this report is available on the Melbourne Water website www.melbournewater.com.au 2 2020-21 Annual Stream Flow Management Plan Report | Annual report for Melbourne Waters Stream Flow Management Plans (SFMP’s): Hoddles Creek, Little Yarra and Don Rivers, Olinda Creek, Plenty River, Steels, Pauls and Dixons Creeks, Stringybark Creek, Woori Yallock Creek. Executive Summary Melbourne Water is responsible for managing 1,813 surface water diverters in the Yarra catchment, parts of the lower Maribyrnong River and some creeks in the western catchments. -

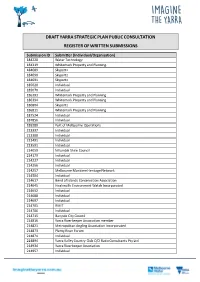

Draft Yarra Strategic Plan Public Consultation Register of Written Submissions

DRAFT YARRA STRATEGIC PLAN PUBLIC CONSULTATION REGISTER OF WRITTEN SUBMISSIONS Submission ID Submitter (Individual/Organisation) 184220 Water Technology 184319 Whitemark Property and Planning. 184689 Skyportz 184690 Skyportz 184691 Skyportz 185020 Individual 185070 Individual 186393 Whitemark Property and Planning 186394 Whitemark Property and Planning 186804 Skyportz 186811 Whitemark Property and Planning 187524 Individual 187856 Individual 189280 Port of Melbourne Operations 213337 Individual 213388 Individual 213491 Individual 213591 Individual 214059 Nillumbik Shire Council 214179 Individual 214227 Individual 214256 Individual 214257 Melbourne Maritime Heritage Network 214504 Individual 214617 Bend of Islands Conservation Association 214645 Healesville Environment Watch Incorporated 214652 Individual 214688 Individual 214697 Individual 214701 RMIT 214706 Individual 214715 Banyule City Council 214816 Yarra Riverkeeper Association member 214821 Metropolitan Angling Association Incorporated 214873 Plenty River Forum 214874 Individual 214894 Yarra Valley Country Club C/O Ratio Consultants Pty Ltd 214934 Yarra Riverkeeper Association 214957 Individual 214971 Individual 214978 Individual 214987 Individual 214995 PLAN A on behalf of Yarra Link 215007 Yarra Riverkeeper Association 215015 Yarra Valley Water 215016 Australian Institute of Landscape Architects 215024 Manningham City Council 215037 Individual 215043 Melbourne Law School, University of Melbourne 215044 Environmental Justice Australia/Yarra Riverkeeper Association 215045 Individual -

Olinda Creek Water Supply Protection Area Stream Flow Management Plan 2007 Olinda Stream Flow Management Plan 2007 Creek

Water Act 1989 Olinda Creek Water Supply Protection Area Stream Flow Management Plan 2007 Olinda Stream Flow Management Plan 2007 Creek Table of Contents Preface 3 Glossary and Acronyms 5 1 Background 6 1.1 What is a Streamflow Management Plan? 6 1.2 Stream Flow Management Plans in the Yarra Basin 6 2 Development of the Plan 6 2.1 How is a Stream Flow Management Plan developed? 6 2.2 Consultation and Information available during Plan development 6 3 The Olinda Creek Catchment 7 3.1 The Water Supply Protection Area 7 3.2 Catchment Description 8 4 Water use within the catchment 9 4.1 Licensed water allocations 9 4.2 Water use not requiring a licence 10 4.3 Current licence management arrangements and current water use 10 5 Determining Environmental Flows 11 5.1 Stream flow in Olinda Creek 11 5.2 Current flows compared to natural flows 12 5.3 Environmental values 12 5.4 Minimum Environmental flows 13 5.5 Issues associated with implementing Minimum Environmental Flows 14 5.6 Flushing flows 16 6 What the Plan contains 17 6.1 Object of the Plan 17 6.2 Administration and Enforcement 18 6.3 Prohibitions on granting new licences 18 6.4 Trading Licences 20 6.5 Unused or “Sleeper” Licences 22 6.6 New Dams 22 6.7 Rostering 22 6.8 Metering 22 6.9 Maintaining Environmental Flows 23 6.10 Licence Conditions 23 6.11 Streamflow monitoring program 23 6.12 Dams on subdivions 23 6.13 Reporting 23 6.14 Monitoring the effects of the Plan 24 6.15 Review of the Plan 24 7 Other Matters 25 8 References 25 9 Appendix 1: Consultative Committee responses to community submission on the draft SFMP 26 Appendix 2: Stream Flow Tender 28 OLINDA CREEK STREAM FLOW MANAGEMENT PLAN 2007 29 Schedule 1: Olinda Creek Water Supply Protection Area 33 Schedule 2: Specific Objectives Proposed by the Olinda Creek Consultative Committee 34 Schedule 3: Licence Conditions 35 Page 2 Preface Throughout Victoria Stream Flow Management Plans (SFMP) are being prepared to better manage the surface water resources of particular catchments. -

Victoria Government Gazette No

Victoria Government Gazette No. S 89 Tuesday 22 June 1999 By Authority. Victorian Government Printer SPECIAL Environment Protection Act 1970 VARIATION OF THE STATE ENVIRONMENT PROTECTION POLICY (WATERS OF VICTORIA) - INSERTION OF SCHEDULE F7. WATERS OF THE YARRA CATCHMENT The Governor in Council under section 16(2) of the Environment Protection Act 1970 and on the recommendation of the Environment Protection Authority declares as follows: Dated 22 June 1999. Responsible Minister: MARIE TEHAN Minister for Conservation and Land Management SHANNON DELLAMARTA Acting Clerk of the Executive Council 1. Contents This Order is divided into parts as follows - PART 1 - PRELIMINARY 2. Purposes 3. Commencement 4. The Principal Policy PART 2 - VARIATION OF THE PRINCIPAL POLICY 5. Insertion of new Schedule F7. Waters of the Yarra Catchment PART 3 - REVOCATION OF REDUNDANT STATE ENVIRONMENT PROTECTION POLICY 6. Revocation of State environment protection policy NO. W-29 (Waters of the Yarra River and Tributaries) PART 1 - PRELIMINARY 2. Purposes The purposes of this Order are to - (a) vary the State environment protection policy (Waters of Victoria) to add to Schedule F a new schedule - Schedule F7. Waters of the Yarra Catchment; and (b) revoke the State environment protection policy NO. W-29 (Waters of the Yarra River and Tributaries) 3. Commencement This Order comes into effect upon publication in the Government Gazette. 4. The Principal Policy In this Order, the State environment protection policy (Waters of Victoria) is called the ÒPrincipal PolicyÓ. PART 2 - VARIATION OF THE PRINCIPAL POLICY 5. Insertion of new Schedule F7. Waters of the Yarra Catchment After Schedule F6. -

Local Context and Site Description

LOCAL CONTEXT AND SITE DESCRIPTION Metropolitan and Regional Context The Greenvale Central Precinct Structure Plan (PSP) area is located approximately 20 kilometres north of the Melbourne CBD, within the Hume Growth Area shown on Plan 1. Melbourne‟s Hume Growth Area generally extends north from Somerton Road (west of Sydney-Melbourne rail line) to Gunns Gully Road at Merrifield. It includes parts of the suburbs of Greenvale and Craigieburn and the localities of Donnybrook, Kalkallo and Beveridge. The Hume Growth Area, along with the Mitchell and Whittlesea Growth Areas, make up the Melbourne North Growth Corridor. The Melbourne North Growth Corridor Plan details the strategic direction for future urban development within this region. The corridor is characterised by strong population growth occurring on various fronts. The population base is projected to increase from its current level of around 170,000 residents to over 220,000 people and has the capacity to provide for at least 68,000 jobs. The North Growth Corridor Plan provides an opportunity to establish new communities to assist in meeting Melbourne‟s urban growth needs over the next 30 years. The plan ensures that the following existing key roles and features are maintained within the Hume Growth Area: A strategic transport corridor of state and national significance; A gateway to Melbourne for interstate and international visitors; Large areas for future employment and industrial development; Highly self-contained working population (with approximately 50% of Hume‟s workforce employed within the municipality); Significant water catchments, creek corridors, remnant vegetation and stone resources on its east and west boundaries; and Important landscape features and biodiversity assets including grasslands and grassy woodlands. -

Sugarloaf Pipeline South-North Transfer Preliminary Business Case Summary Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning

Sugarloaf Pipeline South-North Transfer Preliminary Business Case Summary Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning Sugarloaf Pipeline South-North Transfer 2 Sugarloaf Pipeline South-North Transfer Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning Introduction During the Millennium Pipeline to provide water security The key questions asked in the Drought, Victoria made to towns and communities in both preliminary business case were: large investments in the directions. The work has shown that it is technically feasible to • What infrastructure is required state’s water security. The pump water north with additional for bi-directional pumping and Victorian Desalination works to existing infrastructure. It is it technically feasible? Project was commissioned, would require additional capital • How much water can be investment and it is an option that $1 billion dollars was pumped from the Melbourne government will continue to invested in upgrading the system to the Goulburn River? explore. Goulburn-Murray Irrigation • When can water be transferred District, and the water grid The primary benefits available by and where can it be used? was expanded, including sending water north through the building the Sugarloaf Sugarloaf Pipeline include: • Is the infrastructure financially viable? Pipeline. • supplying water to irrigators and private diverters to improve This document summarises the As a consequence of these agricultural productivity; key findings of the preliminary investments, the Victorian business case. Government has determined that • improving water security for up to an additional 75 gigalitres rural towns and urban centres (GL) per year be available for use connected to the water grid; in northern Victoria. This will support industry and farmers, • making water available to be particularly during dry conditions.