50 YEARS of the VOTING RIGHTS ACT the State of Race in Politics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

V Proof of Residence for Voter Registration

v Proof Of Residence For Voter Registration What Do I Need To Know About Proof Of Residence For Voter Registration? A Proof of Residence document is a document that proves where you live in Wisconsin and is only used when registering to vote. Photo ID is separate, you only show photo ID to prove who you are when you request an absentee ballot or receive a ballot at your polling place. When Do I Have To Provide Proof Of Residence? All voters MUST provide a Proof of Residence Document. If you register to vote by mail, in-person in your clerk’s office, with a Election Registration Official, or at your polling place on Election Day, you need to provide a Proof of Residence document. * If you are an active military voter, or a permanent overseas voter (with no intent to return to the U.S.) you do not need to provide a Proof of Residence document. What Documents Can I Use As Proof Of Residence For Registering? All Proof of Residence documents must include the voter’s name and current residential address. • A current and valid State of Wisconsin Driver License or State ID card. • Any other official identification card or license issued by a Wisconsin governmental body or unit. • Any identification card issued by an employer in the normal course of business and bearing a photo of the card holder, but not including a business card. • A real estate tax bill or receipt for the current year or the year preceding the date of the election. • A university, college, or technical college identification card (must include photo) ONLY if the voter provides a fee receipt dated within the last 9 months or the institution provides a certified housing list, that indicates citizenship, to the municipal clerk. -

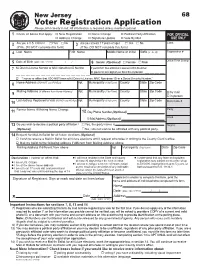

New Jersey 68 Voter Registration Application Please Print Clearly in Ink

New Jersey 68 Voter Registration Application Please print clearly in ink. All information is required unless marked optional. 1 Check all boxes that apply: o New Registration o Name Change o Political Party Affiliation FOR OFFICIAL o Address Change o Signature Update o Vote By Mail USE ONLY 2 Are you a U.S. Citizen? o Yes o No 3 Are you at least 17 years of age? o Yes o No Clerk (If No, DO NOT complete this form) (If No, DO NOT complete this form) 4 Last Name First Name Middle Name or Initial Suffix (Jr., Sr., III) Registration # Office Time Stamp 5 Date of Birth (MM / DD / YYYY) / / 6 Gender (Optional) o Female o Male 7 NJ Driver’s License Number or MVC Non-driver ID Number If you DO NOT have a NJ Driver’s License or MVC Non-Driver ID, provide the last 4 digits of your Social Security Number. __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ o “I swear or affirm that I DO NOT have a NJ Driver’s License, MVC Non-driver ID or a Social Security Number.” Home Address (DO NOT use PO Box) Apt. Municipality (City/Town) County State Zip Code 8 Mailing Address (If different from Home Address) Apt. Municipality (City/Town) County State Zip Code o 9 by mail o in person Last Address Registered to Vote (DO NOT use PO Box) Apt. Municipality (City/Town) County State Zip Code 10 Muni Code # Former Name if Making Name Change Party 11 12 Day Phone Number (Optional) Ward E-Mail Address (Optional) 13 Do you wish to declare a political party affiliation? o Yes, the party name is . -

The Truth About Voter Fraud 7 Clerical Or Typographical Errors 7 Bad “Matching” 8 Jumping to Conclusions 9 Voter Mistakes 11 VI

Brennan Center for Justice at New York University School of Law ABOUT THE BRENNAN CENTER FOR JUSTICE The Brennan Center for Justice at New York University School of Law is a non-partisan public policy and law institute that focuses on fundamental issues of democracy and justice. Our work ranges from voting rights to redistricting reform, from access to the courts to presidential power in the fight against terrorism. A sin- gular institution—part think tank, part public interest law firm, part advocacy group—the Brennan Center combines scholarship, legislative and legal advocacy, and communications to win meaningful, measurable change in the public sector. ABOUT THE BRENNAN CENTER’S VOTING RIGHTS AND ELECTIONS PROJECT The Voting Rights and Elections Project works to expand the franchise, to make it as simple as possible for every eligible American to vote, and to ensure that every vote cast is accurately recorded and counted. The Center’s staff provides top-flight legal and policy assistance on a broad range of election administration issues, including voter registration systems, voting technology, voter identification, statewide voter registration list maintenance, and provisional ballots. © 2007. This paper is covered by the Creative Commons “Attribution-No Derivs-NonCommercial” license (see http://creativecommons.org). It may be reproduced in its entirety as long as the Brennan Center for Justice at NYU School of Law is credited, a link to the Center’s web page is provided, and no charge is imposed. The paper may not be reproduced in part or in altered form, or if a fee is charged, without the Center’s permission. -

Voting and Registration in the Election of November 2004

Voting and Registration in the Election of November 2004 Issued March 2006 Population Characteristics P20-556 This report examines the levels of voting Current and registration in the November 2004 ABOUT THIS REPORT Population presidential election, the characteristics Voting and registration rates histori- Reports of citizens who reported that they were cally have been higher in years with registered for or voted in the election, presidential elections than in con- By and the reasons why registered voters gressional election years. For the Kelly Holder did not vote. purposes of this report, the 2004 The data on voting and registration in this data (a presidential election year) report are based on responses to the are compared with previous presi- November 2004 Current Population dential election years (2000, 1996, Survey (CPS) Voting and Registration 1992, etc.). Supplement, which surveys the civilian noninstitutionalized population in the United States.1 The estimates presented 1992, when 68 percent of voting-age in this report may differ from those based citizens voted.3 The overall number of on administrative data or data from exit people who voted in the November 2004 polls. For more information, see the sec- election was 126 million, a record high tion Accuracy of the Estimates. for a presidential election year. Voter turnout increased by 15 million voters VOTING AND REGISTRATION from the election in 2000. During this OF THE VOTING-AGE same 4-year period, the voting-age CITIZEN POPULATION citizen population increased by 11 mil- lion people. Turnout for the November 2004 Election The registration rate of the voting-age In the presidential election of November citizen population, 72 percent, was 2004, the 64 percent of voting-age citi- higher than the 70 percent registered in zens who voted was higher than the the 2000 election. -

Restoring the Right to Vote | 2 Criminal Disenfranchisement Laws Across the U.S

R E S T O R I N G T H E RIGHT TO VOTE Erika Wood Brennan Center for Justice at New York University School of Law ABOUT THE BRENNAN CENTER FOR JUSTICE The Brennan Center for Justice at New York University School of Law is a non-partisan public policy and law institute that focuses on fundamental issues of democracy and justice. Our work ranges from voting rights to redistricting reform, from access to the courts to presidential power in the fight against terrorism. A singular institution – part think tank, part public interest law firm, part advocacy group – the Brennan Center combines scholarship, legislative and legal advo- cacy, and communications to win meaningful, measurable change in the public sector. ABOUT THE BRENNAN CENTER’S RIGHT TO VOTE PROJECT The Right to Vote Project leads a nationwide campaign to restore voting rights to people with criminal convictions. Brennan Center staff counsels policymakers and advocates, provides legal and constitutional analysis, drafts legislation and regulations, engages in litigation challenging disenfranchising laws, surveys the implementation of existing laws, and promotes the restoration of voting rights through public outreach and education. ABOUT THE AUTHOR Erika Wood is the Deputy Director of the Democracy Program at the Brennan Center for Justice where she lead’s the Right to Vote Project, a national campaign to restore voting rights to people with criminal records, and works on redistricting reform as part of the Center’s Government Accountability Project. Ms. Wood is an Adjunct Professor at NYU Law School where she teaches the Brennan Center Public Policy Advocacy Clinic. -

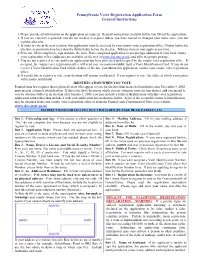

Voter Registration Application Form General Instructions

Pennsylvania Voter Registration Application Form General Instructions 1. Please provide all information on the application as required. Read all instructions carefully before you fill out the application. 2. If you are currently registered, you do not need to re-register unless you have moved or changed your name since you last registered to vote. 3. In order to vote at the next election, this application must be received by your county voter registration office 30 days before the election, or postmarked no later than the thirtieth day before the election. Military electors may apply at any time. 4. Print out, fill in completely, sign and date the form. Place completed application in an envelope addressed to your local county voter registration office (addresses are available on the web at www.dos.state.pa.us) and affix the proper postage. 5. You are not registered to vote until your application has been processed and accepted by the county voter registration office. If accepted, the county voter registration office will send you, via nonforwardable mail, a Voter Identification Card. If you do not receive a Voter Identification Card within 14 days of the date you submit this application, contact your county voter registration office. 6. If you decline to register to vote, your decision will remain confidential. If you register to vote, the office at which you register will remain confidential. IDENTIFICATION WHEN YOU VOTE Pennsylvania law requires that registered voters who appear to vote for the first time in an election district after December 9, 2003 must present a form of identification. -

European Parliament Voter Registration Form Please Fill in All Sections

European Parliament voter registration form Please fill in all sections. Write in black ink and use BLOCK LETTERS. A About you 8 Declaration A1 Your name I declare the following. Last name: 81 I am a citizen of: I I Maiden name: (if applicable) I I Write in the name of the EU member state or I I accession state of which you are a citizen. This is First name (or names) in full: referred to elsewhere in this form as your home I I country. A2 Your address 82 Please tick one box. UK address of where you are applying to register. My current address is as shown in section A2 D The address in section A2 is different from my current address in the UK. My current D address and postcode is: Are you currently living at this address? Yes D No D If 'No', have you made a 'declaration of local connection' by applying to your local electoral registration officer? Postcode I I Yes D No D B3 My name has previously been entered on a register of electors in my home country. A3 Your age Please tick one box. Yes D No D I am 18 or over D I am under 18 D If you ticked 'Yes', please write here the name of the locality or constituency where you were last If you are under 18, please give your date of birth. registered, as far as you know. I I I I B4 I will use any right to vote at the European Where to. -

September 2020 Voter

Volume LXXXV, #02 September 2020 In commemoration of the 100th anniversary of Women’s Suffrage, a brief timeline of Women’s Suffrage activities in the U.S., 1840–1920, can be found on pages 9-13 inside. Descriptions of an opportunity for learning and collegiality in September as well as notice of a public forum on the Electoral College are found on page 3. Inside this issue: The American March to Women’s Suffrage . 1 Sunshine Corner . 7 President’s Corner . 2 LWV-RMA to Assist Research on Women & Politics . .. 7 Fall Member Update Meeting . 3 LWV-RMA Book Club Selects 2020-2021 Books . 8 Public Forum: The Electoral College . 3 The American March to Women’s Suffrage 1800 thru Civil War . .. 9 When, Where, How to Vote, Fall 2020 . 4 The American March to Women’s Suffrage 1866 thru 1900 . 10-11 Government Committee Report . 5 The American March to Women’s Suffrage 1900 thru 1920 . 12-13 Candidate Forums Committee Report . 5 Check Out These Links to Learn More . 13 Vote411 Report . 5 Calendar . 14 Election Services Report . .. 6 Leadership . 15 FEPC Update Report . 6 2 Volume LXXXV, #02 • September 2020 President’s Corner WHAT DOES THE CENTENNIAL OF THE 19TH AMENDMENT MEAN FOR US TODAY? Much of the focus of 19th Amendment Centennial articles, productions and events has been on celebrating the history, the role of black and indigenous women, or the women who have come afterwards, those who benefited from and answered the call for women to engage, exercise and assume political power. But there is another lens with which to look at the Centennial. -

Denmark FRACIT Report Ersboll Online Version

EUDO CITIZENSHIP OBSERVATORY ACCESS TO ELECTORAL RIGHTS DENMARK Eva Ersbøll June 2013 http://eudo-citizenship.eu European University Institute, Florence Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies EUDO Citizenship Observatory Access to Electoral Rights Denmark Eva Ersbøll June 2013 EUDO Citizenship Observatory Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies Access to Electoral Rights Report, RSCAS/EUDO-CIT-ER 2013/7 Badia Fiesolana, San Domenico di Fiesole (FI), Italy © Eva Ersbøll This text may be downloaded only for personal research purposes. Additional reproduction for other purposes, whether in hard copies or electronically, requires the consent of the authors. Requests should be addressed to [email protected] The views expressed in this publication cannot in any circumstances be regarded as the official position of the European Union Published in Italy European University Institute Badia Fiesolana I – 50014 San Domenico di Fiesole (FI) Italy www.eui.eu/RSCAS/Publications/ www.eui.eu cadmus.eui.eu Research for the EUDO Citizenship Observatory Country Reports has been jointly supported, at various times, by the European Commission grant agreements JLS/2007/IP/CA/009 EUCITAC and HOME/2010/EIFX/CA/1774 ACIT, by the European Parliament and by the British Academy Research Project CITMODES (both projects co-directed by the EUI and the University of Edinburgh). The financial support from these projects is gratefully acknowledged. For information about the project please visit the project website at http://eudo-citizenship.eu Access to Electoral Rights Denmark Eva Ersbøll 1. Introduction This report reviews electoral rights and procedures in Denmark. Denmark is a representative democracy where citizens influence political decisions by voting in elections for the national parliament (Folketing), the European Parliament, and in local and regional elections – although there are considerable limitations on the participation of Danish citizens living abroad. -

Report on Political Participation of Mobile EU Citizens: Denmark RSCAS/GLOBALCIT-PP 2018/4 September 2018

COUNTRY REPORT 2018/04 REPORT ON SEPTEMBER POLITICAL 2018 PARTICIPATION OF MOBILE EU CITIZENS: DENMARK AUTHORED BY This report was funded by the Eu- ropean Union’s Rights, Equality and KASPER M. HANSEN Citizenship Programme (2014-2020) © Kasper M. Hansen, 2018 This text may be downloaded only for personal research purposes. Additional reproduction for other purposes, whether in hard copies or electronically, requires the consent of the authors. If cited or quoted, reference should be made to the full name of the author(s), editor(s), the title, the year and the publisher. Requests should be addressed to [email protected]. Views expressed in this publication reflect the opinion of individual authors and not those of the European University Institute. Global Citizenship Observatory (GLOBALCIT) Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies in collaboration with Edinburgh University Law School Report on Political Participation of Mobile EU Citizens: Denmark RSCAS/GLOBALCIT-PP 2018/4 September 2018 © Kasper M. Hansen, 2018 Printed in Italy European University Institute Badia Fiesolana I – 50014 San Domenico di Fiesole (FI) www.eui.eu/RSCAS/Publications/ cadmus.eui.eu Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies The Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies, created in 1992 and currently directed by Professor Brigid Laffan, aims to develop inter-disciplinary and comparative research on the major issues facing the process of European integration, European societies and Europe’s place in 21st century global politics. The Centre is home to a large post-doctoral programme and hosts major research programmes, projects and data sets, in addition to a range of working groups and ad hoc initiatives. -

Voting Criminal Record

Voting WITH A Criminal Record HOW REGISTRATION FORMS FRUSTRATE DEMOCRACY OCTOBER 2008 Voting WITH A Criminal Record HOW REGISTRATION FORMS FRUSTRATE DEMOCRACY Voting With A Criminal Record: How Registration Forms Frustrate Democracy Published October 2008 THE AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION is the nation’s premier guardian of liberty, working daily in courts, legislatures and communities to defend and preserve the individual rights and freedoms guaranteed by the Constitution and the laws of the United States. OFFICERS AND DIRECTORS Nadine Strossen, President Anthony D. Romero, Executive Director Richard Zacks, Treasurer ACLU NATIONAL OFFICE 125 Broad Street, 18th Fl. New York, NY 10004-2400 (212) 549-2500 www.aclu.org ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Nicole Kief, State Strategist with the American Civil Liberties Union’s Racial Justice Program, drafted this report. She would like to thank Laleh Ispahani and Rachel Bloom for their guidance throughout the course of this project, and Aron Cobbs and Sarah Hinger for their research assistance. She is also grateful to Nancy Abudu of the ACLU’s Voting Rights Project, Jessica Hewitt of AIGA Design for Democracy, Erika Wood and Lawrence Norden of the Brennan Center for Justice, and Marshall Clement of the Council of State Governments, and Margaret Love of the Law Office of Margaret Love for their advice. For more information about the ACLU’s work to end felony disfranchisement, visit www.aclu.org/righttovote. Cover Photos: Brande Jackson, Lokahi Outreach (www.lokahioutreach.org) VOTING WITH A CRIMINAL RECORD: HOW REGISTRATION FORMS FRUSTRATE DEMOCRACY CONTENTS Executive Summary . .3 Findings . .6 I: Inaccurate, Incomplete and Misleading Explanations of Who is Ineligible to Vote and for How Long . -

Voter Registration: a Restriction on the Fundamental Right to Vote

Voter Registration: A Restriction on the Fundamental Right to Vote Deborah S. James Fully thirty-five to forty percent of eligible Americans are not registered to vote, and are therefore unable to cast a ballot on election day.' This Note presents a framework for challenging the pre-election day registra- tion requirement as violative of the fundamental right to cast a ballot on election day2 in general purpose elections.3 Currently, one state does not require registration,4 and three states al- low registration on election day.5 Critically, in the remaining states, regis- tration may close up to fifty days prior to the election,6 preventing voting by eligible persons who realize their interest in a particular election only during the increasing exchange of ideas that accompanies the approach of an election. In addition to the closing date obstacle, many of these states' statutes either mandate restrictive registration practices or allow local reg- istrars wide latitude concerning whether to deputize volunteers, establish satellite sites, hold special registration drives, or extend hours.7 As a result 1. Stone, Voter Registration: Context and Results, 17 URB. LAW. 519, 520 (1985). 2. Two members of Congress are currently drafting bills that would mandate election day regis- tration in federal elections, to be introduced to the 100th Cong., 1st Sess. (1987). Telephone inter- views with Candy Nelson, Congressional Fellow to Sen. Alan Cranston (May 28, 1987) and Julian Epstein, Legislative Director to Rep. John Conyers (June 1, 1987). National legislation would re- move the need for case by case review of state registration practices in court.