Little Tokyo Planning & Design Guidelines

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

532-8623 Gardena Bowl Coffee Shop

2015 NISEI WEEK JAPANESE FESTIVAL ANNIVERSARY 7 5 TH ANNUAL JAPANESE FESTIVAL NISEI WEEK Pioneers, Community Service & Inspiration Award Honorees Event Schedules & Festival Map 2015 Queen Candidates Nisei Week Japanese Festival 1934 - 2015: “Let the Good Times Roll” 2014 Nisei Week Japanese Festival Queen Tori Angela Nishinaka-Leon CONTENTS NISEI WEEK FESTIVAL WELCOME FESTIVAL ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS AND INTRODUCTION 2015 Sponsors, Community Friends and Event Sponsors ... 42 Festival Greetings........................................... 10 2015 Nebuta Sponsors ..................................... 50 Grand Marshal: Roy Yamaguchi ............................. 16 2014 Queen’s Treasure Chest ............................... 67 Parade Marshal: Kenny Endo................................ 17 Supporters Ad Index....................................... 104 Pioneers: Richard Fukuhara, Toshio Handa, Kay Inose, 2015 Nisei Week Foundation Board, Madame Matsumae III, George Nagata, David Yanai ........ 24 Committees, and Volunteers............................... 105 Inspiration Award: Dick Sakahara, Michie Sujishi ............ 30 Community Service Awards: East San Gabriel Valley Japanese Community Center, Evening Optimist Club of Gardena, Japanese Restaurant Association of America, Orange County Nikkei Coordinating Council, Pasadena Japanese Cultural Institute, San Fernando Valley Japanese American Community Center, Venice Japanese Community Center, West Los Angeles Japanese American Citizens League ........................ 36 CALENDAR OF EVENTS & FEATURES 2015 -

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD— Extensions of Remarks E303 HON

March 4, 2010 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — Extensions of Remarks E303 you, this country can’t possibly move through the country with its wide assortment of deli- mango, red bean (azuki), strawberry, and va- the next 10 years in a period of relative cious and original bakery items. nilla. strength.’’ Mikawaya manufactures and sells traditional Mikawaya’s traditional Japanese confections Since that speech, more than 200,000 Japanese pastry and confectionary (wagashi), and pastries are still available and made daily Americans have spent 2 years of their lives in mochi ice cream, and gelato. In addition to its at its Los Angeles factory and are still a favor- parts of the world that many of us have never traditional ‘‘mochi-gashi’’ and ‘‘manju’’ that ite in the Asian American community. heard of. And right now, dozens of Peace have been the foundation of the family busi- Corp volunteers from the Seattle area alone ness, Mikawaya has obtained nationwide pop- Always innovators, Mikawaya now manufac- are serving in countries as far as Mali, ularity and success as the creator of Mochi Ice tures and sells gelato—Italian-style ice cream Turkmenistan and Cambodia. Participants Cream along with its gelato offerings. made from milk, sugar, real fruit and other in- have worked on everything from helping farm- Madam Speaker, as Mikawaya celebrates gredients. ers produce more food to stave off hunger to its 100-year anniversary at the Kyoto Grand Along with Mikawaya’s centennial anniver- teaching computer skills and helping govern- Hotel on March 8, I ask my colleagues to sary, the company opened a new 100,000- ments bolster their technology infrastructure. -

Final EIS/EIR

BU24 F2-273 BU24 F2-274 BU24 F2-275 BU24 F2-276 BU24 F2-277 BU24 F2-278 BU24 F2-279 BU24 Reprinted from the Jan. 11, 2007, issue of the Metropolitan News-Enterprise REMINISCING (Column) By ROGER M. GRACE Norwegian Immigrant Operates Premier L.A. Grocery Store Supreme among grocery stores west of the Mississippi a century ago was H. Jevne’s. It was located right here, where I’m now plunking out this column, at 210 S. Spring Street…the location since 1990 of Metropolitan News Company offices. I have no idea what was being sold at this spot where my desk and PC are now. Caviar? Wines? Laundry soap? Cheeses? Perfumes? Mops? Candles? Jevne had them all. Here’s an ad which appeared 100 years ago today in the Los Angeles Times featuring smoked bloaters: Aside from Jevne ads appearing in the local dailies, they were to be found in out-of-state newspapers. Residents elsewhere were urged to send away for a free catalog and place their orders for shipping, or take the train to L.A. to stock up on merchandise. “Buy Groceries in Los Angeles.” That was the heading on a June 18, 1901 Jevne ad published in the Arizona Republic, which continues: “Go to Jevne’s for hundreds of dainty delicacies that no other grocery store in the Pacific southwest carries....Make a list before you leave on a trip to the coast.” A July 17, 1901 ad in the same newspaper advises: “Free writing and waiting room at Jevne’s in Los Angeles. -

Substitute - Item 15

SUBSTITUTE - ITEM 15 MOTION Frances Hashimoto was born at the Poston War Relocation Center in Arizona during World War II. After the war, the family returned to Little Tokyo where she spent much of her time at the family business. She graduated from the University of Southern California and worked as an elementary school teacher for four years, however due to family needs Ms. Hashimoto entered the family business full time, and began learning the art of making Japanese confections. In 1970, she became the CEO of the Mikawaya Japanese pastry company which also ultimately produced the now very popular Mochi Ice Cream. As a successful entrepreneur, Ms. Hashimoto has grown the company from a small neighborhood store into a large corporation with five retail branches. The Mikawaya, has been offering traditional Japanese confectionaries to the communities in Southern California since 1910. Under Ms. Hashimoto's leadership, Mikawaya has expanded its operations significantly. Now its signature product, "Mochi Ice Cream," is sold in many Japanese restaurants and supermarkets all over the country, enabling many people to experience and appreciate the Japanese confectionary culture. Due to her great passion for the community in which she grew, Ms. Hashimoto began her service in many local organizations and has served in many varying posts. From 1994 to 2008, Ms. Hashimoto served as the president of Little Tokyo Business Association. During her tenure The Little Tokyo Business Association was revitalized and continues proudly to serve the community. One of her numerous accomplishments is that she strengthened the ties between Little Tokyo and Minami Otsu Dori Shotengai in Nagoya by delegation exchanges, organizing fundraising for Nisei Week, arranging business seminars, and lobbying the city governments of both countries. -

Little Tokyo Community Council 369 East First Street Los Angeles, California 90012 213 625.0414 Ext 5720 Fax 213 625.1770

little Tokyo Community Council 369 East First Street Los Angeles, California 90012 213 625.0414 ext 5720 Fax 213 625.1770 http://ltcc.janet.org October 27, 2009 The Honorable Ara Najarian Chairman Board of Directors Los Angeles County MetropOlitan Transportation Authority .One Gateway Plaza Los Angeles, California 90012 Re: Downtown Regional Connector Dear Mr. Najarian: The Little Tokyo Community Council (LTCC) is an association that represents over 90+ businesses, nonprofit and for profit organizations, educational, religiOUSand cultural institutions and resident organizations in Little Tokyo. The LTCC has been working with the Metro staff over the last few months on the proposed Downtown Regional Connector to review various options, their potential advantages and disadvantages for the community, and mitigation issues. After sharing information about options for the Regional Connector, many concerns have been raised regarding potential negative impacts at the intersections involving Alameda Avenue, negative impacts on local business due to long construction phases, as well as other concerns. These issues are of vital concern to the LTCC because of Little Tokyo's importance as an historical ethnic neighborhood and our desire to preserve this unique enclave for generations to come so that it can continue to be a cultural symbol for the Japanese American community as well as a tremendous visitor attraction for the City. We want to work with the MTA in finding the best solution to our concerns as well as developing a public transportation that will benefit the City at large. To further the discussion for seeking the best option, the LTCC "The Little TokyoCommunity Council is a nonprofit 501(c)(3) Board of Directors presented the following motion at its recent meeting: to which has 90+ member have MTA look at altering the proposed Underground Emphasis Option, organizations whose mission by continuing to tunnel underground below 1st and Alameda for an is to ensure that Little Tokyo underground station in Little Tokyo. -

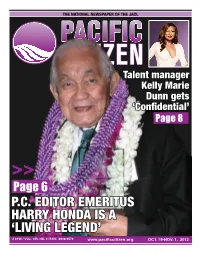

P.C. Editor Emeritus Harry Honda Is a 'Living Legend'

THE NATIONAL NEWSPAPER OF THE JACL Talent manager Kelly Marie Dunn gets ‘Confidential’ Page 8 >> Page 6 P.C. EDITOR EMERITUS HARRY HONDA IS A ‘Living Legend’ # 3199 / VOL. 155, NO. 8 ISSN: 0030-8579 www.pacificcitizen.org OCT. 19-NOV. 1, 2012 2 Oct. 19-Nov. 1, 2012 LETTERS HOW TO REACH US E-mail: [email protected] Online: www.pacificcitizen.org Tel: (213) 620-1767 LETTERS TO THE EDITOR … Fax: (213) 620-1768 Mail: 250 E. 1st St., Suite 301 Los Angeles, CA 90012 STAFF the ‘power of words’ has many meanings it’s important for japanese ameriCans to Executive Editor STAY POLITICALLY ACTIVE Assistant Editor ;A> Reporter # -31 #4;@;&<>1-0 Nalea J. Ko In your Aug. 17-Sept. 6, 2012, As a child growing up in the East issue, it was quite interesting to Bay, I recall my mother was always Business Manager read the articles that used the involved with voter registration Susan Yokoyama abbreviation POW to stand for and she served as a poll worker Circulation #3 ,;A@4I;/7@;@41 Eva Lau-Ting :-@5;:-8/;:B1:@5;: “Power of Words.” Previously, for elections. I think she was inspired by her interest in politics the abbreviation POW had (she received her B.A. from U.C. Berkeley in political science The Pacific Citizen newspaper only meant “Prisoner of War” before being shipped off to a relocation camp). Going through her (ISSN: 0030-8579) is published semi-monthly (except once in #3 to me, and the articles thus papers recently, I found she was also a League of Women Voters December and January) by the 5:?@-88? .;->0;205>1/@;>? reminded me of an incident member. -

Japan and LA Report FINAL.Indd

Growing Together Japan& Los Angeles County Growing Together Japan& Los Angeles County The Fast Facts Japan is the #1 source of Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) into L.A. County Japan is the #2 trading partner of the Los Angeles Customs District (LACD) L.A. County is home to the largest Japanese-American Community in the U.S. Prepared by: Nancy D. Sidhu, Ph.D., Chief Economist Ferdinando Guerra, Associate Economist and Principal Researcher Kimberly Ritter, Associate Economist Los Angeles County Economic Development Corporation Kyser Center for Economic Research 444 S. Flower St., 34th Floor Los Angeles, CA 90071 Tel: (213) 622-4300 or (888) 4-LAEDC-1 Fax: (213)-622-7100 E-mail: [email protected] Web: http://www.laedc.org The LAEDC, the region’s premier business leadership organization, is a private, non-profi t 501(c)3 organization established in 1981. As Southern California’s premier business leadership organization, the mission of the LAEDC is to attract, retain, and grow businesses and jobs for the regions of Los Angeles County. Since 1996, the LAEDC has helped retain or attract more than 163,500 jobs, providing $8.0 billion in direct economic impact from salaries and more than $136 million in tax revenue benefi t to local governments and education in Los Angeles County. Regional Leadership The members of the LAEDC are civic leaders and ranking executives of the region’s leading public and private organizations. Through fi nancial support and direct participation in the mission, programs, and public policy initiatives of the LAEDC, the members are committed to playing a decisive role in shaping the region’s economic future. -

Final Mochi Interactive PDF Nicole Harripersad

Mochi By Nicole Harripersad Table of Contents Desserts with Mochi ........................................................... Page 5 Mochi Ice Cream!! ............................................................ Page 6 How do you make Mochi? .................................................... Page 7 Tips and Tricks ................................................................. Page 8 Mochi Today ................................................................... Page 9 Mochi in NYC ................................................................... Page 10 Mochi at home Easter Mochi Mochi at a restaurant What Is Mochi? the body and increase energy. Mochi’s sweet taste nourishes the pancreas, spleen, and stomach. Mochi is an excellent source of food for people who are in a weak condition. Japanese farm- ers and laborers favor mochi during colder months because of its reputation for increasing one’s stamina. So this can be a big help for students taking major exams during schools Mochi is recommended for Fresh Daifuku health problems such as anemia, imbalances in blood sugar, and weak intestines. to people for good health and ylose. In Women who are pregnant fortune. Later on mochi was mochi, the amylose content and are lactating can benefit, eaten for various occasions or was insignificant, which because it strengthens both as a regular snack . results in its gel like texture. the mother and child which Mochi is a Mochi has a strange mixed Mochi is also said to give encourages a plentiful japanese rice cake made of structure which contained strength to those eating it. supply of milk. With its high Mochigome, a short grain amylopectin gel, starch grains, The use of two mochi calcium and iron mostly the glutinous sweet rice that is and air bubbles.This rice has symbolizes the passage of mochi is traditionally given much sticker than regualr rice a lack of amylose,(a type of time, one for the previous year to women after childbirth. -

THE NATIONAL NEWSPAPER of the JACL Nov

THE NATIONAL NEWSPAPER OF THE JACL Nov. 9-15, 2018 V E T ER A N S 0 A Y WWW .PACIFICCITIZEN.ORG #33321 VOL. 167, No. 9 ISSN: 0030·8579 2 Nov. 9-15. 2018 NATIONAL PACIFIC e CITIZEN Susan Lee, David Moon, Lily Qi, 2018 MIDTERM ELECTIONS Kris Valderrama HOW TO REACH US Massachusetts: Tackey Chan, Email : [email protected] By JACL National to 1.4 million people - the largest Guam: Lou Leon Guerrero, Michael Sonia Chang-Diaz,Rady Mom, Tram Online: www.pacificcitizen.org enfranchisement since the Voting San Nicolas Nguyen, Dean Tran, Donald Wong Tel: (213) 620-1767 he 2018 midterms have seen Mail: 123 Ellison S.OnizukaSt.,Suite 313 Rights Act. Also in Florida, Amend Michigan: Stephanie Chang, Padma some victories for equity as Hawaii: Henry I.C.Aquino, Della Au Los Angeles, CA 90012 ment 11 will revise the Florida Con Belatti, Tom Brower, Rida Cabanilla, Kuppa voters around the country STAFF T stitution to remove a provision that Romy Cachola, Ty J.K. Cullen, Lynn Minnesota: Fue Lee, Kaohly moved to elect officials who better Executive Editor "aliens ineligible for citizenship" DeCoite, Stacelynn Kehaulani Eli, Her, Samantha Vang, Jay Xiong, Allison Haramoto represent them, their communities and this nation's increasing diversity. are not permitted to own property. Jamie Kalani English, Tulsi Gab TouXiong Senior Editor This is reminiscent of the Alien Land bard, Noe Galea'i, Cedric Asuega New Hampshire: Aboul Khan, Latha Digital & Social Media For the first time in history, 100 George Johnston Laws that prevented many Issei from Gates, SharonHar, Breene Harimoto, Mangipudi, Julie Radhakrishnan women will sit in the House of Rep Business Manager owning property prior to the war. -

Pg 4 Photo: Paul Kitagaki Jr

THE NATIONAL NEWSPAPER OF THE JACL JAs and Afri- can Americans collaborate in S.F.’s redistrict- ing process. >> pg 3 pg 3 Photog Chronicles WWII Internment With Before/After Photos PHOTO: SEATTTLE POST-INTELLIGENCER pg 4 PHOTO: PAUL KITAGAKI JR. © COPYRIGHT 2012 >> Female sumo “Comic Book wrestling is Men’s” Ming working hard Chen is the to catch up go-to guy to the boys. on the show. pg 9 pg 5 DANE POTTER/AMC # 3186 / VOL. 154, NO. 6 ISSN: 0030-8579 WWW.PACIFICCITIZEN.ORG APRIL 06 - APRIL 19, 2012 2 APR. 6-19, 2012 SPRING CAMPAIGN/COMMENTARY PACIFIC CITIZEN PACIFIC CITIZEN SPRING CAMPAIGN COMMENTARY HOW to REACH US E-mail: [email protected] Online: www.pacificcitizen.org Tel: (213) 620-1767 MAGNIFYING THE VOICE OF UPDATE ON STAFF REVIEWS Fax: (213) 620-1768 Mail: 250 E. First Street, Suite 301 AND BELLEVUE CONVENTION Los Angeles, CA 90012 JACL MEMBERS Staff Executive Editor By Paul Niwa By Gail Sueki Caroline Y. Aoyagi-Stom Assistant Editor One of the things I remember about my As the national JACL vice president for Lynda Lin general operations I am also the personnel grandfather, Henry Fukuhara, was the mag- Reporter azines on his coffee table. When I became a committee chair. This year the committee Nalea J. Ko had a critical job to perform: providing a college student, I started a habit of digging Business Manager through that stack of papers to pull out the recommendation to the national board for Staci Hisayasu the selection of a national director. The out- latest edition of the Pacific Citizen. -

Extensions of Remarks E301 EXTENSIONS of REMARKS

March 4, 2010 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — Extensions of Remarks E301 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS OPEN AND TRANSPARENT HONORING 19TH CENTURY AFRI- award will be presented during the Commit- SMITHSONIAN ACT CAN-AMERICAN LEGISLATORS OF tee’s annual Lincoln Day Dinner at the Merion TEXAS Tribute House in Merion Station, Pennsyl- vania. HON. ELEANOR HOLMES NORTON HON. EDDIE BERNICE JOHNSON Madam Speaker, I ask that my colleagues OF THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA OF TEXAS join me today in extending our deepest appre- ciation to Lewis F. ‘‘Lew’’ Gould Jr. for his ex- IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES emplary leadership, civic engagement and Thursday, March 4, 2010 Thursday, March 4, 2010 dedication to making Lower Merion Township Ms. EDDIE BERNICE JOHNSON of Texas. a great place to live, work and raise a family. Ms. NORTON. Madam Speaker, today I in- Madam Speaker, I rise today to recognize and troduce the Open and Transparent Smithso- voice my support for a new monument that will f nian Act to further ensure that the Smithsonian be unveiled at the Texas State Cemetery in CONGRATULATING THOMAS Institution is accountable to the public for the Austin, Texas, on March 30, 2010, to com- THAYER FOR RECEIVING THE taxpayer funds it receives. This bill provides memorate the state’s African-American legisla- INTERNATIONAL CIRCLE OF EX- that, for the purposes of the Freedom of Infor- tors of the 19th century. CELLENCE AWARD mation Act, FOIA, and the Privacy Act, the This monument will serve as a reminder to Smithsonian shall be considered a federal all Texans of the role that African Americans agency. -

LITTLE TOKYO Community Design Overlay (CDO) DISTRICT リトル東京地区の都市デザイン Introduction

LITTLE TOKYO Community Design Overlay (CDO) DISTRICT リトル東京地区の都市デザイン Introduction The Little Tokyo Community Design Overlay (CDO) Tokyo could potentially face pressures for change creates thoughtful development guidelines that in the near future. reflect the community’s vision for the neighbor- hood. This document establishes long-term goals In light of these trends, the unique character of and creates design principles that will be used to Little Tokyo cannot be taken for granted. These guide future development within the CDO area. significant public investments could create new development pressures for the neighborhood. Today, Little Tokyo remains an active commercial, However, if carefully guided, these investments residential, religious, cultural, and historical commu- represent an opportunity to preserve, enhance, nity center in Downtown Los Angeles. In addition and strengthen the community. to being the center for Japanese-American culture and community, Little Tokyo represents a unique The intent of the Little Tokyo CDO is to provide intersection of art and history in a neighborhood guidance and direction for the design of new connected through pedestrian-oriented streets that buildings and public spaces, to promote a pedes- contribute to a distinctive identity and sense of place. trian-friendly environment, enhance the physical appearance of the area, and preserve the histor- The neighborhood is part of the greater Downtown ical and cultural identity of Little Tokyo. These Los Angeles community, an interconnected and guidelines are intended to help ensure that both rapidly changing area of the city. At the heart of public and private projects in the area respect the changes in recent years are significant mass trans- character of the neighborhood.