Psychological Impairment and Coping Strategies During the COVID-19

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Assessment of Adherence to the Core Elements of Hospital Antibiotic Stewardship Programs: a Survey of the Tertiary Care Hospitals in Punjab, Pakistan

antibiotics Article Assessment of Adherence to the Core Elements of Hospital Antibiotic Stewardship Programs: A Survey of the Tertiary Care Hospitals in Punjab, Pakistan Naeem Mubarak 1,* , Asma Sarwar Khan 1, Taheer Zahid 1 , Umm e Barirah Ijaz 1, Muhammad Majid Aziz 1, Rabeel Khan 1, Khalid Mahmood 2 , Nasira Saif-ur-Rehman 1,* and Che Suraya Zin 3,* 1 Department of Pharmacy Practice, Lahore Medical & Dental College, University of Health Sciences, Lahore 54600, Pakistan; [email protected] (A.S.K.); [email protected] (T.Z.); [email protected] (U.e.B.I.); [email protected] (M.M.A.); [email protected] (R.K.) 2 Institute of Information Management, University of the Punjab, Lahore 54000, Pakistan; [email protected] 3 Kulliyyah of Pharmacy, International Islamic University Malaysia, Kuantan 25200, Malaysia * Correspondence: [email protected] (N.M.); [email protected] (N.S.-u.-R.); [email protected] (C.S.Z.) Abstract: Background: To restrain antibiotic resistance, the Centers for Disease Control and Preven- tion (CDC), United States of America, urges all hospital settings to implement the Core Elements of Hospital Antibiotic Stewardship Programs (CEHASP). However, the concept of hospital-based antibiotic stewardship programs is relatively new in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. Aim: To Citation: Mubarak, N.; Khan, A.S.; appraise the adherence of the tertiary care hospitals to seven CEHASPs. Design and Setting: A cross- Zahid, T.; Ijaz, U.e.B.; Aziz, M.M.; sectional study in the tertiary care hospitals in Punjab, Pakistan. Method: CEHASP assessment tool, Khan, R.; Mahmood, K.; (a checklist) was used to collect data from the eligible hospitals based on purposive sampling. -

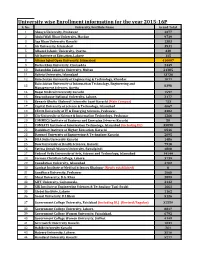

University Wise Enrollment Information for the Year 2015-16P S

University wise Enrollment information for the year 2015-16P S. No. University/Institute Name Grand Total 1 Abasyn University, Peshawar 4377 2 Abdul Wali Khan University, Mardan 9739 3 Aga Khan University Karachi 1383 4 Air University, Islamabad 3531 5 Alhamd Islamic University, Quetta. 338 6 Ali Institute of Education, Lahore 115 8 Allama Iqbal Open University, Islamabad 416607 9 Bacha Khan University, Charsadda 2449 10 Bahauddin Zakariya University, Multan 21385 11 Bahria University, Islamabad 13736 12 Balochistan University of Engineering & Technology, Khuzdar 1071 Balochistan University of Information Technology, Engineering and 13 8398 Management Sciences, Quetta 14 Baqai Medical University Karachi 1597 15 Beaconhouse National University, Lahore. 2177 16 Benazir Bhutto Shaheed University Lyari Karachi (Main Campus) 753 17 Capital University of Science & Technology, Islamabad 4067 18 CECOS University of IT & Emerging Sciences, Peshawar. 3382 19 City University of Science & Information Technology, Peshawar 1266 20 COMMECS Institute of Business and Emerging Sciences Karachi 50 21 COMSATS Institute of Information Technology, Islamabad (including DL) 35890 22 Dadabhoy Institute of Higher Education, Karachi 6546 23 Dawood University of Engineering & Technology Karachi 2095 24 DHA Suffa University Karachi 1486 25 Dow University of Health Sciences, Karachi 7918 26 Fatima Jinnah Women University, Rawalpindi 4808 27 Federal Urdu University of Arts, Science and Technology, Islamabad 14144 28 Forman Christian College, Lahore. 3739 29 Foundation University, Islamabad 4702 30 Gambat Institute of Medical Sciences Khairpur (Newly established) 0 31 Gandhara University, Peshawar 1068 32 Ghazi University, D.G. Khan 2899 33 GIFT University, Gujranwala. 2132 34 GIK Institute of Engineering Sciences & Technology Topi-Swabi 1661 35 Global Institute, Lahore 1162 36 Gomal University, D.I.Khan 5126 37 Government College University, Faislabad (including DL) (Revised/Regular) 32559 38 Government College University, Lahore. -

HEC RECOGNIZED LOCAL JOURNALS (Languages, Arts & Humanities)

HEC RECOGNIZED LOCAL JOURNALS (Languages, Arts & Humanities). The HEC is not responsible for the content of external internet sites. Y' CATEGORY JOURNALS: Acceptable for Tenure Track System, BPS appointments, HEC Approved Supervisor and Publication of research of Ph.D. work until 30th June 2016 S. No. Journal Name ISSN University Editor/Contact Person Subject w.e.f. Tel/Mob No. Fax No. E-mail Website The Iqbal review Iqbal Academy, 6th Floor, Aiwan-i- 1 0021-0773 Muhammad Suheyl Umar Iqbal Studies Jun-05 42-6314510 42-6314496 [email protected] http://www.allamaiqbal.com/ – A quarterly Journal Iqbal, Egerton Road, Lahore Department of English, University of May,12 2 Kashmir Journal of Language Research 1028-6640 Azad Jammu & Kashmir, Dr. Raja Nasim Akhter Language (in category 'Z' from Sep,08 99243131 Ext 2278 www.ajku.edu.pk Muzaffarabad till Apr,11) Journal of Research (Urdu) Formerly February 2015 (In 'Z' Department of Urdu Bahauddin 3 Journal of Research (Languages & Islamic 1726-9067 Dr.Rubina Tareen Urdu Category from Dec, 08 till 061-9210117 061-9210108 [email protected] http://www.bzu.edu.pk/jrlanguages/defalt.htm Zakariya University, Multan Studies) January 2015) February 2015 (In 'Z' Department of Urdu, Shah Abdul 4 Almas 1818-9296 Dr.M. Yusuf Khushk Urdu Category from Jun, 05 till 0243-9280291 0243-9280291 [email protected] http://www.salu.edu.pk/research/publication/journals/urdu/almas/ Latif University, Khairpur January 2015) February 2015 (In 'Z' Department of Urdu, Government 5 Tahqeeq Nama 1997-7611 Dr.M. Haroon Qadir Urdu Category from June 2005 042-99213339 - [email protected] http://gcu.edu.pk/TehqNama.htm College University, Lahore till January 2015) Gurmani Centre for Languages and February 2015 (In 'Z' 6 Bunyad 2225-5083 Literature, Lahore University of Dr. -

General Merit List of Reserved Seats for P.U Teachers for Admission to Pharm.D 1St Professional Morning Class Session 2020-2025

PUNJAB UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF PHARMACY UNIVERSITY OF THE PUNJAB, LAHORE. General Merit list of Reserved seats for P.U Teachers for Admission to Pharm.D 1st Professional Morning class session 2020-2025. Note: Any Candidate who has submitted the complete admission form on college admission portal, i.e., admissionpucp.edu.pk or pucp.edu.pk with fullfilling all requirements, but his/her name is not inculde in the General merit list should report to the college admission office before 03-11-2020. No complaint will be entertained after 03-11-2020. The University Reserves the Right to correct any Typographical Error, Ommision etc. Sr. Year of % Merit Late Year Final Merit Form ID Name of Student Father name Status No. Passing Marks Deduction Marks 1 DB5866 MUHAMMAD HAMZA SHOAIB HAJI MUHAMMAD SHOAIB KHAN 2020 94.655 0 94.655 Son 2 DB11359 HAFIZA SARA HASSAN HAFIZ HASAN MADNI 2020 94.255 0 94.255 Daughter 3 DB6061 KHANSA IJAZ MUHAMMAD IJAZ 2020 91.236 0 91.236 Daughter 4 DB7458 IZZA ALMATEEN SOHAIL SOHAIL AFZAL TAHIR 2020 90.273 0 90.273 Daughter Daughter 5 DB10100 AYESHA KHALIL KHALIL AHMAD 2020 88.836 0 88.836 Letter Required 6 DB5267 AZQA AHMAD AHMAD ISLAM 2020 88.764 0 88.764 Daughter 7 DB6048 MUSFIRA FATIMA MALIK AHMED SHER AWAN 2020 87.400 0 87.400 Daughter 8 DB8059 AREEBA AMER SYED AMER MAHMOOD 2020 86.182 0 86.182 Daughter 9 DB5799 SHEHROZE RAUF SHAKOORI ABDUL RAUF SHAKOORI 2020 83.132 0 83.132 Son Daughter 10 DB8639 AYESHA SOHAIL BUTT 2019 83.436 2 81.436 Letter Required 11 DB12029 UM E ABIHA SIKANDARR SIKANDAR HAYAT KHAN 2017 80.582 6 -

MLIS Curriculum at Punjab University: Perception and Reflections

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Library Philosophy and Practice (e-journal) Libraries at University of Nebraska-Lincoln March 2010 MLIS Curriculum at Punjab University: Perception and Reflections Nosheen Warraich University of the Punjab, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac Part of the Library and Information Science Commons Warraich, Nosheen, "MLIS Curriculum at Punjab University: Perception and Reflections" (2010). Library Philosophy and Practice (e-journal). 339. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac/339 Library Philosophy and Practice 2010 ISSN 1522-0222 MLIS Curriculum at Punjab University: Perception and Reflections Nosheen Warraich Lecturer LIS Department University of the Punjab Lahore, Pakistan Introduction Khurshaid (1992, p. 13) writes that, “LIS Education was started at the University of the Punjab Lahore by Asa Don Dickinson, an American librarian and student of Melvil Dewey, in 1915 as a post- graduate certificate program.” Bansal and TIkku (1988, p. 397) add that, “University of the Punjab was the first university outside the USA to introduce regular training in librarianship.” An American professor, James C. R. Ewing, then Vice-Chancellor of the University of the Punjab (1910-1917), suggested the recruitment of a trained librarian. The objective was to train those already working in libraries and to reorganize the Punjab University Library. The suggestion was approved by the university administration. Dickenson, who applied for the position in response to an advertisement published in the American press, was appointed for one year (Anwar, 1992; Qarshi, 1992; Ameen, 2007). Dickinson reached Lahore on October 12, 1915 and began a series of lectures on modern library methods in November 1915. -

Information Needs and Seeking Behavior of Paramedical Staff in the Hospitals of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Library Philosophy and Practice (e-journal) Libraries at University of Nebraska-Lincoln Spring 4-13-2021 Information Needs and Seeking Behavior of Paramedical Staff in the Hospitals of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan Sumera Akram Department of Library and Information Science, Khushal Khan Khattak University Karak, [email protected] Ghalib Khan Department of Library and Information Science, Khushal Khan Khattak University Karak, [email protected] Saeed Ullah Jan Department of Library and Information Science, Khushal Khan Khattak University Karak, [email protected] Muhammad Shehryar Department of Library and Information Science, Khushal Khan Khattak University Karak, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac Part of the Library and Information Science Commons Akram, Sumera; Khan, Ghalib; Jan, Saeed Ullah; and Shehryar, Muhammad, "Information Needs and Seeking Behavior of Paramedical Staff in the Hospitals of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan" (2021). Library Philosophy and Practice (e-journal). 5463. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac/5463 Information Needs and Seeking Behavior of Paramedical Staff in the Hospitals of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan Sumera Akram1 Ghalib Khan Dr.1 Saeed Ullah Jan Dr.2 Muhammad Shehryar2 Abstract The main theme of this study was to examine the information needs and seeking behavior of Female Paramedical Staff in Government Hospitals of District Karak, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. Survey-based method was used to carried out the study. The population of this study was 110 Female paramedical staff in two government hospitals. Data was collected through questionnaires for data collection. The findings of the study revealed that paramedics mostly need information for clinical works, caretaking of patients, problems of patients, new medical trends and health policies, and self-development. -

Prof. Dr. Shahida Manzoor

PROF. DR. SHAHIDA MANZOOR Principal, University College of Art & Design, University of the Punjab, Allama Iqbal Campus, Lahore, Pakistan Phone: Office: 042-99212729-30, Cell: 0333-6507103 E-mail: [email protected] [email protected] EDUCATION Ph. D. in Fine Arts (2003) Ohio University, USA. Topic of Ph.D. Thesis: Chaos Theory and Robert Wilson: A Critical Analysis of Wilson's Visual Arts and Theatrical Performances.. M.F.A. in Painting (Gold Medalist) 1987, University of the Punjab, Lahore, Pakistan. TEACHING/ADMINISTRATIVE EXPERIENCE Four years teaching experience at Ohio University, U.S.A 1997-2001. Taught Humanity courses to undergraduate students i.e. Painting, Sculpture, Architecture, Theater and Music. Twenty-nine years teaching experience teaching graduate and post- graduate classes at the University of the Punjab from 28.11.1989 - to date. teaching mainly painting, Western art, Modern art, Post- modern/contemporary and History of Islamic Architecture, Fourteen Years post Ph. D Experience. Teaching, Theories, History of Art, Aesthetics, Research Methodologies to Art History and Studio Practice doctoral Students. Coordinator, Research Centre of UCAD w.e.f. 1.6.2006 to 30.8.2010. Principal, University College of Art & Design, Punjab University, Lahore w.e.f. 8.8.2014 Warden/ Superintendent, Fatima Jinnah Hall, Girls Hostel #1, Punjab University, Lahore w.e.f. 2006- to date. HONORS First Pakistani woman to earn Ph.D. degree in Fine Arts from USA (see video attached). Appointed as a Student Judge, in the Athens County Court, Athens, Ohio-USA Selection as a Faculty Member of College of Fine Arts, Ohio University (2001). -

World Directory of Medical Schools

WORLD DIRECTORY OF MEDICAL SCHOOLS WORLD HEALTH• ORGANIZATION PALA!S DES N ATIONS GENEVA 1957 lst edition, 1953 2nd edition (revised and enlarged), 1957 PRINTED IN SWITZERLAND CONTENTS Page Introduction . 5 Explanatory notes to lists of medical schools 7 Details of educational systems and lists of medical teaching institutions, in alphabetical order of countries 11 Annex 1. Africa: medical schools and physicians 303 Annex 2. North and Central America: medical schools and physicians . 304 Annex 3. South America: medical schools and physicians 305 Annex 4. Asia, eastern: medical schools and physicians . 306 Annex 5. Asia, western: medical schools and physicians 307 Annex 6. Europe: medical schools and physicians 308 Annex 7. Oceania: medical schools and physicians 309 Annex 8. World totals . 310 Annex 9. Population per physician 311 Annex 10. Division of the medical curriculum, in years 313 28695 INTRODUCTION The Second Edition of the World Directory of Medical Schools, like its predecessor, lists institutions of medical education in more than eighty countries and gives a few pertinent facts about each. However, its scope has been enlarged, in that general statements describing the salient features of undergraduate medical training in each country have also been included. No attempt has been made to draw firm conclusions or to make pro nouncements on medical education as a world-wide phenomenon. The descriptive accounts and factual material which make up this Directory may be considered as part of the raw data on which the reader can base his own independent analysis; they are intended to be no more than a general guide, and investigators in the subject of medical education should not expect to :find a complete report therein. -

CV of Dr. Afifa Anjum

AFIFA ANJUM Lecturer Institute of Applied Psychology University of the Punjab, Quaid-e-Azam Campus, Lahore. Phone: 042-9231235, 92-300-4405065 Email: [email protected], [email protected] EDUCATIONAL QUALIFICATION PhD Scholar Department of Applied Psychology, University of the Punjab, Lahore (2012 onwards) MPhil leading to PhD, MPhil course work completed (2010-12) Bachelor of Education Allama Iqbal Open University, Islamabad (2003) Masters of Science (Applied Psychology) University of the Punjab (2001) Bachelor of Arts Lahore College for Women, Lahore (1999) SPECIAL ACHEIVEMENTS Got HEC Indigenous Scholarship for PhD Topped in PhD course work in the Department of Applied Psychology, University of the Punjab, Lahore. Topped in M. Phil. course work in the Department of Applied Psychology, University of the Punjab, Lahore. Gold Medal, in M.Sc (Applied Psychology) in University of the Punjab, Lahore. Bronze Medal in B.A. Examination, University of the Punjab, Lahore. Bronze Medal in Intermediate Examination, BISE, Lahore. Silver Medal in Matriculation Examination, BISE, Lahore. WORK EXPERIENCE Lecturer (August 2004-to date) Department of Applied Psychology, University of the Punjab, Lahore. School Psychologist/Teacher (March 2003 – July, 2004) Laurel Bank School, Singhpura , Lahore Research Assistant (May – July 2002) 1 With researcher from Oxford University, London in the area of quality of education in government and private schools in Lahore as determined by school financial status, teachers’ qualification and teaching and students IQ and abilities. COURSES TAUGHT Applied Statistics in Psychology, Ethical Issues in Psychology, Psychological Testing and Assessment, Social Psychology, Research Methodology, Abnormal Psychology, Health Psychology, Computer Usage MEMBERSHIP ON GRADUATE DEGREE COMMITTIES Member Semester / Examination Committee of the Department Incharge Examinations ( M.Sc. -

College Codes (Outside the United States)

COLLEGE CODES (OUTSIDE THE UNITED STATES) ACT CODE COLLEGE NAME COUNTRY 7143 ARGENTINA UNIV OF MANAGEMENT ARGENTINA 7139 NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF ENTRE RIOS ARGENTINA 6694 NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF TUCUMAN ARGENTINA 7205 TECHNICAL INST OF BUENOS AIRES ARGENTINA 6673 UNIVERSIDAD DE BELGRANO ARGENTINA 6000 BALLARAT COLLEGE OF ADVANCED EDUCATION AUSTRALIA 7271 BOND UNIVERSITY AUSTRALIA 7122 CENTRAL QUEENSLAND UNIVERSITY AUSTRALIA 7334 CHARLES STURT UNIVERSITY AUSTRALIA 6610 CURTIN UNIVERSITY EXCHANGE PROG AUSTRALIA 6600 CURTIN UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY AUSTRALIA 7038 DEAKIN UNIVERSITY AUSTRALIA 6863 EDITH COWAN UNIVERSITY AUSTRALIA 7090 GRIFFITH UNIVERSITY AUSTRALIA 6901 LA TROBE UNIVERSITY AUSTRALIA 6001 MACQUARIE UNIVERSITY AUSTRALIA 6497 MELBOURNE COLLEGE OF ADV EDUCATION AUSTRALIA 6832 MONASH UNIVERSITY AUSTRALIA 7281 PERTH INST OF BUSINESS & TECH AUSTRALIA 6002 QUEENSLAND INSTITUTE OF TECH AUSTRALIA 6341 ROYAL MELBOURNE INST TECH EXCHANGE PROG AUSTRALIA 6537 ROYAL MELBOURNE INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY AUSTRALIA 6671 SWINBURNE INSTITUTE OF TECH AUSTRALIA 7296 THE UNIVERSITY OF MELBOURNE AUSTRALIA 7317 UNIV OF MELBOURNE EXCHANGE PROGRAM AUSTRALIA 7287 UNIV OF NEW SO WALES EXCHG PROG AUSTRALIA 6737 UNIV OF QUEENSLAND EXCHANGE PROGRAM AUSTRALIA 6756 UNIV OF SYDNEY EXCHANGE PROGRAM AUSTRALIA 7289 UNIV OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA EXCHG PRO AUSTRALIA 7332 UNIVERSITY OF ADELAIDE AUSTRALIA 7142 UNIVERSITY OF CANBERRA AUSTRALIA 7027 UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES AUSTRALIA 7276 UNIVERSITY OF NEWCASTLE AUSTRALIA 6331 UNIVERSITY OF QUEENSLAND AUSTRALIA 7265 UNIVERSITY -

ARSLAN SHEIKH Assistant Librarian COMSATS University Islamabad, Park Road, Islamabad-Pakistan

ARSLAN SHEIKH Assistant Librarian COMSATS University Islamabad, Park Road, Islamabad-Pakistan. +92-51-90495069 | +92-321-9423071 | [email protected] : https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2661-6383 Career Objective To learn and grow in the field of Library and Information Management, being affiliated with academic as well as professional organizations. Education PhD in Library & Information Science - (In Progress) Humboldt University of Berlin, Germany MS in Library & Information Science - 2019 CGPA 3.31/4.00 Sarhad University of Science & Information Technology, Peshawar Master of Library & Information Science - 2006 CGPA 3.26/4.00 University of the Punjab, Lahore Work Experience Assistant Librarian - 09/2009 to Present COMSATS University Islamabad Reference and research services Electronic document delivery Support of researchers in literature searching Guidance in writing research articles/theses and dissertations Help in referencing and citation management Guidance of researchers in publishing their research Plagiarism detection in theses, articles & academic assignments Editor, LIS Bulletin (a quarterly newsletter) Visiting Lecturer - 10/2020 to 03/2021 Department of Information Management, University of Sargodha Taught Course (Information Technology: Concepts and Applications) Taught Course (Library Automation Systems) Assistant Librarian - 05/2008 to 08/2009 National University (FAST), Islamabad In charge circulation, technical and reference services Digital reference services Handling of digital resources Orientation for new library patrons Compiler, “Faculty Annual Research Publications Report” Librarian - 11/2006 to 05/2008 Hajvery University (HU), Lahore Pioneer Librarian of “Euro Campus Library” Management of all library operations Library automation Serials management Acquisition of library materials Librarian (Intern) - 06/2006 to 08/2006 Lahore University of Management Sciences (LUMS), Lahore Research Journal Articles 1. -

Faculty of Pharmacy

University of Central Punjab Faculty of Pharmacy It is my privilege to serve as Dean for this prestigious Faculty of Pharmacy, University of the Central Punjab, Lahore. Our Faculty of university is one of the leading universities to de-velop your career and to make you a precious asset of the country. In order to meet the challenges of tomorrow, the university is Pharmacy trying to provide high standard profes-sional education in a very conducive environment to all our students. Faculty of Pharma-cy is home to world-class faculty, dedicated students and innovative researchers working towards im-proving medications and medication-related health outcomes. After the recognition of Pharmacy education by Pharmacy Council of Pakistan and Higher Education Commission in 2011, our faculty has made enormous strides in meeting specific needs of both students and community, exploring new frontiers in drug discovery and development, pharmaceutical sciences, and translational clinical re-search. Prof. Dr. Muhammad Jamshaid These labours have led to more than 30 manuscripts in the Dean past three years. Here at the faculty, we value innovation, learning, advancement of knowledge, research and its applica-tions toward improving the use of medications in society, pharmaceutical care and professional-ism. Diversity in all of its forms is the core thought of faculty’s research and develop-ment. We continually endeavour to augment our betterment and extend our national and in-ternational influence through quality education and research. We welcome your comments and sugges-tions for improvement of pharmacy education and research. I will expect you to participate in all healthy and academic activities of the faculty as well as the university.