Manual Scavengers: a Blind Spot in Urban Development Discourse

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No. Email id Remarks 20001 MUDKONDWAR SHRUTIKA HOSPITAL, TAHSIL Male 9420020369 [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 PRASHANT NAMDEORAO OFFICE ROAD, AT/P/TAL- GEORAI, 431127 BEED Maharashtra 20002 RADHIKA BABURAJ FLAT NO.10-E, ABAD MAINE Female 9886745848 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 PLAZA OPP.CMFRI, MARINE 8281300696 DRIVE, KOCHI, KERALA 682018 Kerela 20003 KULKARNI VAISHALI HARISH CHANDRA RESEARCH Female 0532 2274022 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 MADHUKAR INSTITUTE, CHHATNAG ROAD, 8874709114 JHUSI, ALLAHABAD 211019 ALLAHABAD Uttar Pradesh 20004 BICHU VAISHALI 6, KOLABA HOUSE, BPT OFFICENT Female 022 22182011 / NOT RENEW SHRIRANG QUARTERS, DUMYANE RD., 9819791683 COLABA 400005 MUMBAI Maharashtra 20005 DOSHI DOLLY MAHENDRA 7-A, PUTLIBAI BHAVAN, ZAVER Female 9892399719 [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 ROAD, MULUND (W) 400080 MUMBAI Maharashtra 20006 PRABHU SAYALI GAJANAN F1,CHINTAMANI PLAZA, KUDAL Female 02362 223223 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 OPP POLICE STATION,MAIN ROAD 9422434365 KUDAL 416520 SINDHUDURG Maharashtra 20007 RUKADIKAR WAHEEDA 385/B, ALISHAN BUILDING, Female 9890346988 DR.NAUSHAD.INAMDAR@GMA RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 BABASAHEB MHAISAL VES, PANCHIL NAGAR, IL.COM MEHDHE PLOT- 13, MIRAJ 416410 SANGLI Maharashtra 20008 GHORPADE TEJAL A-7 / A-8, SHIVSHAKTI APT., Male 02312650525 / NOT RENEW CHANDRAHAS GIANT HOUSE, SARLAKSHAN 9226377667 PARK KOLHAPUR Maharashtra 20009 JAIN MAMTA -

Unclaimed Dividend

Nature of Date of transfer to Name Address Payment Amount IEPF A B RAHANE 24 SQUADRON AIR FORCE C/O 56 APO Dividend 150.00 02-OCT-2018 A K ASTHANA BRANCH RECRUITING OFFICE COLABA BOMBAY Dividend 37.50 02-OCT-2018 A KRISHNAMOORTHI NO:8,IST FLOOR SECOND STREET,MANDAPAM ROAD KILPAUK MADRAS Dividend 300.00 02-OCT-2018 A MUTHALAGAN NEW NO : 1/194 ELANJAVOOR HIRUDAYAPURAM(P O) THIRUMAYAM(TK) PUDHUKOTTAI Dividend 15.00 02-OCT-2018 A NARASIMHAIAH C/O SRI LAXMI VENKETESWAR MEDICAL AGENCIES RAJAVEEDHI GADWAL Dividend 150.00 02-OCT-2018 A P CHAUDHARY C/O MEHATA INVESTMENT 62, NAVI PETH , NR. MALAZA MARKET M.H JALGAON Dividend 150.00 02-OCT-2018 A PARANDHAMA NAIDU BRANCH MANAGER STATE BANK OF INDIA DIST:CHITTOOR,AP NAGALAPURAM Dividend 112.50 02-OCT-2018 A RAMASUBRAMAIAN NO. 22, DHANLEELA APPT., VALIPIR NAKA, BAIL BAZAR, KALYAN (W), MAHARASHTRA KALYAN Dividend 150.00 02-OCT-2018 A SREENIVASA MOORTHY 3-6-294 HYDERAGUDA HYDERABAD Dividend 150.00 02-OCT-2018 A V NARASIMHARAO C-133 P V TOWNSHIP BANGLAW AREA MANUGURU Dividend 262.50 02-OCT-2018 A VENKI TESWARDKAMATH CANARA BANK 5/A,21, SAHAJANAND PATH MUMBAI Dividend 150.00 02-OCT-2018 ABBAS TAIYEBALI GOLWALA C/O A T GOLWALA 207 SAIFEE JUBILEE HUSEINI BLDG 3RD FLOOR BOMBAY 40000 BOMBAY Dividend 150.00 02-OCT-2018 ABDUL KHALIK HARUNRAHID DIST.BHARUCH (GUJ) KANTHARIA Dividend 150.00 02-OCT-2018 ABDUL SALIM AJ R T C F TERLS VSSC TRIVANDRUM Dividend 150.00 02-OCT-2018 ABDUL WAHAB 3696 AUSTODIA MOTI VAHOR VAD AHMEDABAD Dividend 150.00 02-OCT-2018 ABHA ANAND PRAKASHGANDHI DOOR DARSHAN KENDRA POST BOX 5 KOTHI COMPOUND RAJKOT Dividend 150.00 02-OCT-2018 ABHAY KUMAR DOSHI DHIRENDRA SOTRES MAIN BAZAR JASDAN RAJKOT Dividend 150.00 02-OCT-2018 ABHAY KUMAR DOSHI DHIRENDRA SOTRES MAIN BAZAR JASDAN RAJKOT Dividend 150.00 02-OCT-2018 ABHINAV KUMAR 5712, GEORGE STREET, APT NO. -

380 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

380 bus time schedule & line map 380 Amrut Nagar (Vikhroli-W) View In Website Mode The 380 bus line (Amrut Nagar (Vikhroli-W)) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Amrut Nagar (Vikhroli-W): 5:12 AM - 5:52 AM (2) Anushakti Nagar: 8:18 AM - 8:10 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 380 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 380 bus arriving. Direction: Amrut Nagar (Vikhroli-W) 380 bus Time Schedule 44 stops Amrut Nagar (Vikhroli-W) Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 5:12 AM - 5:52 AM Monday 5:12 AM - 5:52 AM Anushakti Nagar V.N. Purav Marg, Mumbai Tuesday 5:12 AM - 5:52 AM Agarwadi (Mankhurd) Wednesday 5:12 AM - 5:52 AM V.N. Purav Marg, Mumbai Thursday 5:12 AM - 5:52 AM Mankhurd Railway Station (N) Friday 5:12 AM - 5:52 AM Maharashtra Nagar Saturday 5:12 AM - 5:52 AM Mohite Patil Nagar Railway Colony 380 bus Info Annabhau Sathe Ngr. Direction: Amrut Nagar (Vikhroli-W) Stops: 44 B.M.C.Compost Plant Trip Duration: 33 min Line Summary: Anushakti Nagar, Agarwadi Bainganwadi (Mankhurd), Mankhurd Railway Station (N), Maharashtra Nagar, Mohite Patil Nagar, Railway Colony, Annabhau Sathe Ngr., B.M.C.Compost Plant, Bainganwadi Bainganwadi, Bainganwadi, 600 Tenament Gate, Tata Nagar / Sambhaji Nagar, Deonar Municipal Cly., 600 Tenament Gate Deonar Police Station, New Gautam Ngr., Ashish Nagar, Narayan Guru High School, Shivsena O∆ce, Tata Nagar / Sambhaji Nagar Ambedkar Nagar, Amar Mahal, Amar Mahal, Sahakar Talkies, Pestam Sagar / Glass Factory, Sommaiya Deonar Municipal Cly. -

Sr. No. Ward Name of Socities Addresses of Societies Daily Waste

Bulk Generator Addresses-Eastern Suburbs Daily Waste Sr. Generation by Ward Name of Socities Addresses of Societies No. Bulk Generators (in Kgs) L & T, Gate No.5, Sakivihar Road, Kulra (W), L & T, Gate No.5, Sakivihar Road, 1 460 Mumbai – 400072 Kulra (W), Mumbai – 400072 (0.46) Light Hall, Sakivihar Road, Kulra (W), Light Hall, Sakivihar Road, Kulra (W), 2 740 Mumbai – 400072 Mumbai – 400072 (0.74) Ashok Tower, Marva Road, Kulra (W), Ashok Tower, Marva Road, Kulra 3 290 Mumbai – 400072 (W), Mumbai – 400072 (0.29) Satair Lake side CHS, Mountain Satair Lake side CHS, Mountain Bridge CHS Bridge CHS (New Mhada Colony), 4 (New Mhada Colony), Powai, JVL Road, 630 Powai, JVL Road, Kulra (W), Mumbai Kulra (W), Mumbai – 400072 – 400072 (0.632) Manav Sthal Heights, Marva Road, Kurla (w), Manav Sthal Heights, Marva Road, 5 265 Mumbai-400072 Kurla (w), Mumbai-400072 (0.267) N.G. Complex, Marva road, Kurla (w), N.G. Complex, Marva road, Kurla 6 225 Mumbai-400072 (w), Mumbai-400072 (0.225) Ashok Vihar CHS, Marva Road, Kurla (W), Ashok Vihar CHS, Marva Road, Kurla 7 160 Mumbai – 400072. (W), Mumbai – 400072.(0.160) Udyan Society, Marwa Road, Kurla (W), Udyan Society, Marwa Road, Kurla 8 140 Mumbai-400072 (W), Mumbai-400072 (0.139) Om Shanti complex Bhudhaji wadi Om Shanti complex Bhudhaji wadi lane, 9 lane, Sakivihar road, Kurla (w), 195 Sakivihar road, Kurla (w), Mumbai-400072 Mumbai-400072 (0.196) Harshvardhan Soc, Sakivihar Road, Kurla Harshvardhan Soc, Sakivihar Road, 10 125 (W), Mumbai-400072 Kurla (W), Mumbai-400072 (0.127) Adityavardhan Soc, (Aristocrat Lane), Kurla Adityavardhan Soc, (Aristocrat Lane), 11 140 (W), Mumbai-400072 Kurla (W), Mumbai-400072 (0.138) Tata Symphany CHS, Nahar Amrut Tata Symphany CHS, Nahar Amrut Shakti 12 Shakti Road, Kurla (W), Mumbai – 175 Road, Kurla (W), Mumbai – 400072. -

SR NO First Name Middle Name Last Name Address Pincode Folio

SR NO First Name Middle Name Last Name Address Pincode Folio Amount 1 A SPRAKASH REDDY 25 A D REGIMENT C/O 56 APO AMBALA CANTT 133001 0000IN30047642435822 22.50 2 A THYAGRAJ 19 JAYA CHEDANAGAR CHEMBUR MUMBAI 400089 0000000000VQA0017773 135.00 3 A SRINIVAS FLAT NO 305 BUILDING NO 30 VSNL STAFF QTRS OSHIWARA JOGESHWARI MUMBAI 400102 0000IN30047641828243 1,800.00 4 A PURUSHOTHAM C/O SREE KRISHNA MURTY & SON MEDICAL STORES 9 10 32 D S TEMPLE STREET WARANGAL AP 506002 0000IN30102220028476 90.00 5 A VASUNDHARA 29-19-70 II FLR DORNAKAL ROAD VIJAYAWADA 520002 0000000000VQA0034395 405.00 6 A H SRINIVAS H NO 2-220, NEAR S B H, MADHURANAGAR, KAKINADA, 533004 0000IN30226910944446 112.50 7 A R BASHEER D. NO. 10-24-1038 JUMMA MASJID ROAD, BUNDER MANGALORE 575001 0000000000VQA0032687 135.00 8 A NATARAJAN ANUGRAHA 9 SUBADRAL STREET TRIPLICANE CHENNAI 600005 0000000000VQA0042317 135.00 9 A GAYATHRI BHASKARAAN 48/B16 GIRIAPPA ROAD T NAGAR CHENNAI 600017 0000000000VQA0041978 135.00 10 A VATSALA BHASKARAN 48/B16 GIRIAPPA ROAD T NAGAR CHENNAI 600017 0000000000VQA0041977 135.00 11 A DHEENADAYALAN 14 AND 15 BALASUBRAMANI STREET GAJAVINAYAGA CITY, VENKATAPURAM CHENNAI, TAMILNADU 600053 0000IN30154914678295 1,350.00 12 A AYINAN NO 34 JEEVANANDAM STREET VINAYAKAPURAM AMBATTUR CHENNAI 600053 0000000000VQA0042517 135.00 13 A RAJASHANMUGA SUNDARAM NO 5 THELUNGU STREET ORATHANADU POST AND TK THANJAVUR 614625 0000IN30177414782892 180.00 14 A PALANICHAMY 1 / 28B ANNA COLONY KONAR CHATRAM MALLIYAMPATTU POST TRICHY 620102 0000IN30108022454737 112.50 15 A Vasanthi W/o G -

Bulk Generator Addresses.Xlsx

Bulk Generator Addresses-Eastern Suburbs Daily Waste Generation by Sr No. Ward Name of Socities Addresses of Societies Remarks Bulk Generators (in Kgs) L & T, Gate No.5, Sakivihar Road, Kulra (W), Mumbai – L & T, Gate No.5, Sakivihar Road, 400072 (0.46) Kulra (W), Mumbai – 400072 (0.46) 460 Light Hall, Sakivihar Road, Kulra (W), Mumbai – 400072 Light Hall, Sakivihar Road, Kulra (0.74) (W), Mumbai – 400072 (0.74) 740 Ashok Tower, Marva Road, Kulra (W), Mumbai – 400072 Ashok Tower, Marva Road, Kulra (0.29) (W), Mumbai – 400072 (0.29) 290 Satair Lake side CHS, Mountain Bridge CHS (New Mhada Satair Lake side CHS, Mountain Colony), Powai, JVL Road, Kulra (W), Mumbai – 400072 Bridge CHS (New Mhada Colony), (0.632) Powai, JVL Road, Kulra (W), Mumbai – 400072 (0.632) 632 Manav Sthal Heights, Marva Road, Kurla (w), Mumbai- Manav Sthal Heights, Marva Road, 400072 (0.267) Kurla (w), Mumbai-400072 (0.267) 267 N.G. Complex, Marva road, Kurla (w), Mumbai-400072 N.G. Complex, Marva road, Kurla (0.225) (w), Mumbai-400072 (0.225) 225 Ashok Vihar CHS, Marva Road, Kurla (W), Mumbai – Ashok Vihar CHS, Marva Road, 400072.(0.160) Kurla (W), Mumbai – 400072.(0.160) 160 Udyan Society, Marwa Road, Kurla (W), Mumbai-400072 Udyan Society, Marwa Road, (0.139) Kurla (W), Mumbai-400072 (0.139) 139 Om Shanti complex Bhudhaji wadi lane, Sakivihar road, Om Shanti complex Bhudhaji wadi Kurla (w), Mumbai-400072 (0.196) lane, Sakivihar road, Kurla (w), Mumbai-400072 (0.196) 196 Harshvardhan Soc, Sakivihar Road, Kurla (W), Mumbai- Harshvardhan Soc, Sakivihar 400072 (0.127) Road, Kurla (W), Mumbai-400072 (0.127) 127 Adityavardhan Soc, (Aristocrat Lane), Kurla (W), Mumbai- Adityavardhan Soc, (Aristocrat 400072 (0.138) Lane), Kurla (W), Mumbai-400072 (0.138) 138 Tata Symphany CHS, Nahar Amrut Shakti Road, Kurla Tata Symphany CHS, Nahar (W), Mumbai – 400072. -

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No. Email Id Remarks 9421864344 022 25401313 / 9869262391 Bhaveshwarikar

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No. Email id Remarks 10001 SALPHALE VITTHAL AT POST UMARI (MOTHI) TAL.DIST- Male DEFAULTER SHANKARRAO AKOLA NAME REMOVED 444302 AKOLA MAHARASHTRA 10002 JAGGI RAMANJIT KAUR J.S.JAGGI, GOVIND NAGAR, Male DEFAULTER JASWANT SINGH RAJAPETH, NAME REMOVED AMRAVATI MAHARASHTRA 10003 BAVISKAR DILIP VITHALRAO PLOT NO.2-B, SHIVNAGAR, Male DEFAULTER NR.SHARDA CHOWK, BVS STOP, NAME REMOVED SANGAM TALKIES, NAGPUR MAHARASHTRA 10004 SOMANI VINODKUMAR MAIN ROAD, MANWATH Male 9421864344 RENEWAL UP TO 2018 GOPIKISHAN 431505 PARBHANI Maharashtra 10005 KARMALKAR BHAVESHVARI 11, BHARAT SADAN, 2 ND FLOOR, Female 022 25401313 / bhaveshwarikarmalka@gma NOT RENEW RAVINDRA S.V.ROAD, NAUPADA, THANE 9869262391 il.com (WEST) 400602 THANE Maharashtra 10006 NIRMALKAR DEVENDRA AT- MAREGAON, PO / TA- Male 9423652964 RENEWAL UP TO 2018 VIRUPAKSH MAREGAON, 445303 YAVATMAL Maharashtra 10007 PATIL PREMCHANDRA PATIPURA, WARD NO.18, Male DEFAULTER BHALCHANDRA NAME REMOVED 445001 YAVATMAL MAHARASHTRA 10008 KHAN ALIMKHAN SUJATKHAN AT-PO- LADKHED TA- DARWHA Male 9763175228 NOT RENEW 445208 YAVATMAL Maharashtra 10009 DHANGAWHAL PLINTH HOUSE, 4/A, DHARTI Male 9422288171 RENEWAL UP TO 05/06/2018 SUBHASHKUMAR KHANDU COLONY, NR.G.T.P.STOP, DEOPUR AGRA RD. 424005 DHULE Maharashtra 10010 PATIL SURENDRANATH A/P - PALE KHO. TAL - KALWAN Male 02592 248013 / NOT RENEW DHARMARAJ 9423481207 NASIK Maharashtra 10011 DHANGE PARVEZ ABBAS GREEN ACE RESIDENCY, FLT NO Male 9890207717 RENEWAL UP TO 05/06/2018 402, PLOT NO 73/3, 74/3 SEC- 27, SEAWOODS, -

2 Bedroom Apartment / Flat for Sale in Powai

https://www.propertywala.com/P50510427 Home » Mumbai Properties » Residential properties for sale in Mumbai » Apartments / Flats for sale in Powai, Mumbai » Property P50510427 2 Bedroom Apartment / Flat for sale in Powai, Mumbai 1.53 crore Ready To Move Apartment In Sun City Complex Advertiser Details Suncity Complex, Adi Shankaracharya Marg, Powai, Mum… Area: 825 SqFeet ▾ Bedrooms: Two Bathrooms: Two Floor: Sixth Total Floors: Seven Facing: East Furnished: Unfurnished Transaction: Resale Property Price: 15,300,000 Rate: 18,545 per SqFeet -30% Scan QR code to get the contact info on your mobile View all properties by India Property Solution Age Of Construction: 12 Years Possession: Immediate/Ready to move Description This is a meticulously designed 2 bhk resale apartment located in powai, central Mumbai suburbs. The flat is located in a co-Operative society. The flat is a spacious property and is ready to move in. Located in an integrated society of sun city complex , it has 2 bathroom(S) and 1 balcony(S). This is a feng shui/vaastu compliant property and has vitrified flooring. It requires a payable monthly maintenance costs of rs. 5000. It is a west facing property which offers a wonderful view of main road. It is a 5-10 year old property, located on the 7th floor. Full power back up. The unit is located in a gated society. The property offers specifications such as lift(S), park, water storage, intercom facility, security/fire alarm, internet/wi-Fi connectivity, water purifier, piped-Gas, fitness centre/gym, water softening plant and waste disposal. The apartment is approximately priced at rs. -

Bus-Shelter-Advertising.Pdf

1 ONE STOP MARKETING 2 What Are You Looking For? AIRLINE/AIRPORT CINEMA DIGITAL NEWSPAPER RADIO TELEVISION MAGAZINE SERVICES OUTDOOR NON TRADITIONAL 3 Bus Shelter @ INR 35,000/- Per Month Bus Shelter @ INR 35,000/- Per Month Powai, Mumbai Suresh Nagar, Mumbai Near L&T, Powai Garden, Powai Military Road Juhu-Versova Link Road ,Bharat Nagar/Petrol Pump Bus Shelter @ INR 35,000/- Per Month Bus Shelter @ INR 35,000/- Per Month Juhu, Mumbai VN Purav Marg, Mumbai Juhu S.Parulekar Marg, Traffic Towrds Juhu Bus Station Marathi Vidnyan Parishad, V. N. Purav Road, Chunabhatti Bus Shelter @ INR 35,000/- Per Month Bus Shelter @ INR 35,000/- Per Month Andheri East, Mumbai Andheri East, Mumbai International Airport Road, Sahar Road, Ambassador Outside Techno Mall, Jogeshwari Link Road, Behram Hotel Bagh 4 Bus Shelter @ INR 35,000/- Per Month Bus Shelter @ INR 35,000/- Per Month Lohar Chawl, Mumbai Lad Wadi, Mumbai Kalbadevi Road ,Princess Street 2 Kalbadevi Road ,Princess Street 1 Bus Shelter @ INR 35,000/- Per Month Bus Shelter @ INR 35,000/- Per Month Savarkar Nagar, Mumbai Mahim Nature park, Mumbai Near L&T, Powai Garden, Powai Military Road Dharavi Depot, Dumping Road, Dharavi Bus Shelter @ INR 35,000/- Per Month Bus Shelter @ INR 35,000/- Per Month Antop Hill, Mumbai Bharat Nagar, Mumbai Antop Hill, Shaikh Misri Road, Antop Hill Juhu-Versova Link Road ,Bharat Nagar/Petrol Pump 5 Bus Shelter @ INR 35,000/- Per Month Bus Shelter @ INR 35,000/- Per Month Wadala, Mumbai Kurla East, Mumbai Wadala Station, Kidwai Marg, Wadala S.T. Depot (Kurla East), S.T. -

3 Bedroom Apartment / Flat for Sale in L&T Emerald Isle, Powai

https://www.propertywala.com/P13656643 Home » Mumbai Properties » Residential properties for sale in Mumbai » Apartments / Flats for sale in Powai, Mumbai » Property P13656643 3 Bedroom Apartment / Flat for sale in L&T Emerald Isle, Powai, Mumbai 4.55 crores Apartment In L And T Emerald Isle, Mumbai Advertiser Details L&T Emerald Isle,Saki Vihar Road, Powai, Mumbai - 4000… Project/Society: L&T Emerald Isle Area: 202.06 SqMeters ▾ Bedrooms: Three Bathrooms: Four Transaction: Resale Property Price: 45,500,000 Rate: 2.25 lakhs per SqMeter -25% Scan QR code to get the contact info on your mobile Possession: Immediate/Ready to move View all properties by Dinesh Property Solutions Description A 3 bhk flat is available for sale in central mumbai suburbs powai. This property is a part of parappa. The Pictures built-Up area is 2175 sq.Ft. The carpet area is 1450 sq.Ft. It has more than two bathrooms.The apartment has 2 balconies. Located on the 3rd floor of 27 floors. The expected price of this apartment is rs 4.55 crore () The co-Operative society property offers 2 covered parking and open parking. When you contact, don't forget to mention that you found this ad on PropertyWala.com. Features Other features Builtup Area: 202.06 sq.m. Carpet Area: 134.71 sq.m. Super Builtup Area: 204.39 sq.m. Co-operative Society ownership North-East Facing Balconies: 2 Floor: 3rd of 27 Floors Immediate posession 0 to 1 year old Society: L and T Emerald Isle Granite Flooring Furnishing: Unfurnished Gated Community Reserved Parking Location Project Pictures Bird -

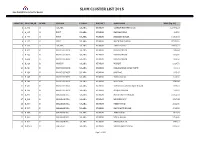

List of Slum Cluster 2015

SLUM CLUSTER LIST 2015 Slum Rehabilitation Authority, Mumbai OBJECTID CLUSTER_ID WARD VILLAGE TALUKA DISTRICT SLUM NAME AREA (Sq. M.) 1 A_001 A COLABA COLABA MUMBAI GANESH MURTHI NAGAR 120771.23 2 A_005 A FORT COLABA MUMBAI BANGALIPURA 318.50 3 A_006 A FORT COLABA MUMBAI NARIMAN NAGAR 14315.98 4 A_007 A FORT COLABA MUMBAI MACHIMAR NAGAR 37181.09 5 A_009 A COLABA COLABA MUMBAI GEETA NAGAR 26501.21 6 B_021 B PRINCESS DOCK COLABA MUMBAI DANA BANDAR 939.53 7 B_022 B PRINCESS DOCK COLABA MUMBAI DANA BANDAR 1292.90 8 B_023 B PRINCESS DOCK COLABA MUMBAI DANA BANDAR 318.67 9 B_029 B MANDVI COLABA MUMBAI MANDVI 1324.71 10 B_034 B PRINCESS DOCK COLABA MUMBAI NALABANDAR JOPAD PATTI 600.14 11 B_039 B PRINCESS DOCK COLABA MUMBAI JHOPDAS 908.47 12 B_045 B PRINCESS DOCK COLABA MUMBAI INDRA NAGAR 1026.09 13 B_046 B PRINCESS DOCK COLABA MUMBAI MAZGAON 1541.46 14 B_047 B PRINCESS DOCK COLABA MUMBAI SUBHASHCHANDRA BOSE NAGAR 848.16 15 B_049 B PRINCESS DOCK COLABA MUMBAI MASJID BANDAR 277.27 16 D_001 D MALABAR HILL COLABA MUMBAI MATA PARVATI NAGAR 21352.02 17 D_003 D MALABAR HILL COLABA MUMBAI BRANHDHARY 1597.88 18 D_006 D MALABAR HILL COLABA MUMBAI PREM NAGAR 3211.09 19 D_007 D MALABAR HILL COLABA MUMBAI NAVSHANTI NAGAR 4013.82 20 D_008 D MALABAR HILL COLABA MUMBAI ASHA NAGAR 1899.04 21 D_009 D MALABAR HILL COLABA MUMBAI SIMLA NAGAR 9706.69 22 D_010 D MALABAR HILL COLABA MUMBAI SHIVAJI NAGAR 1841.12 23 D_015A D GIRGAUM COLABA MUMBAI SIDHDHARTH NAGAR 2189.50 Page 1 of 101 SLUM CLUSTER LIST 2015 Slum Rehabilitation Authority, Mumbai OBJECTID CLUSTER_ID WARD VILLAGE TALUKA DISTRICT SLUM NAME AREA (Sq. -

Date of AGM(DD-MON-YYYY) 09-AUG-2018

Note: This sheet is applicable for uploading the particulars related to the unclaimed and unpaid amount pending with company. Make sure that the details are in accordance with the information already provided in e-form IEPF-2 CIN/BCIN L24110MH1956PLC010806 Prefill Company/Bank Name CLARIANT CHEMICALS (INDIA) LIMITED Date Of AGM(DD-MON-YYYY) 09-AUG-2018 Sum of unpaid and unclaimed dividend 3803100.00 Sum of interest on matured debentures 0.00 Sum of matured deposit 0.00 Sum of interest on matured deposit 0.00 Sum of matured debentures 0.00 Sum of interest on application money due for refund 0.00 Sum of application money due for refund 0.00 Redemption amount of preference shares 0.00 Sales proceed for fractional shares 0.00 Validate Clear Proposed Date of Investor First Investor Middle Investor Last Father/Husband Father/Husband Father/Husband Last DP Id-Client Id- Amount Address Country State District Pin Code Folio Number Investment Type transfer to IEPF Name Name Name First Name Middle Name Name Account Number transferred (DD-MON-YYYY) THOLUR P O PARAPPUR DIST CLAR000000000A00 Amount for unclaimed and A J DANIEL AJJOHN INDIA Kerala 680552 5932.50 02-Oct-2019 TRICHUR KERALA TRICHUR 3572 unpaid dividend INDAS SECURITIES LIMITED 101 CLAR000000000A00 Amount for unclaimed and A J SEBASTIAN AVJOSEPH PIONEER TOWERS MARINE DRIVE INDIA Kerala 682031 192.50 02-Oct-2019 3813 unpaid dividend COCHIN ERNAKULAM RAMACHANDRA 23/10 GANGADHARA CHETTY CLAR000000000A00 Amount for unclaimed and A K ACCHANNA INDIA Karnataka 560042 3500.00 02-Oct-2019 PRABHU