Doing Women's Film & Television History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

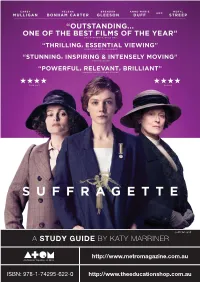

Suffragette Study Guide

© ATOM 2015 A STUDY GUIDE BY KATY MARRINER http://www.metromagazine.com.au ISBN: 978-1-74295-622-0 http://www.theeducationshop.com.au Running time: 106 minutes » SUFFRAGETTE Suffragette (2015) is a feature film directed by Sarah Gavron. The film provides a fictional account of a group of East London women who realised that polite, law-abiding protests were not going to get them very far in the battle for voting rights in early 20th century Britain. click on arrow hyperlink CONTENTS click on arrow hyperlink click on arrow hyperlink 3 CURRICULUM LINKS 19 8. Never surrender click on arrow hyperlink 3 STORY 20 9. Dreams 6 THE SUFFRAGETTE MOVEMENT 21 EXTENDED RESPONSE TOPICS 8 CHARACTERS 21 The Australian Suffragette Movement 10 ANALYSING KEY SEQUENCES 23 Gender justice 10 1. Votes for women 23 Inspiring women 11 2. Under surveillance 23 Social change SCREEN EDUCATION © ATOM 2015 © ATOM SCREEN EDUCATION 12 3. Giving testimony 23 Suffragette online 14 4. They lied to us 24 ABOUT THE FILMMAKERS 15 5. Mrs Pankhurst 25 APPENDIX 1 17 6. ‘I am a suffragette after all.’ 26 APPENDIX 2 18 7. Nothing left to lose 2 » CURRICULUM LINKS Suffragette is suitable viewing for students in Years 9 – 12. The film can be used as a resource in English, Civics and Citizenship, History, Media, Politics and Sociology. Links can also be made to the Australian Curriculum general capabilities: Literacy, Critical and Creative Thinking, Personal and Social Capability and Ethical Understanding. Teachers should consult the Australian Curriculum online at http://www.australiancurriculum.edu.au/ and curriculum outlines relevant to these studies in their state or territory. -

Makers: Women in Hollywood

WOMEN IN HOLLYWOOD OVERVIEW: MAKERS: Women In Hollywood showcases the women of showbiz, from the earliest pioneers to present-day power players, as they influence the creation of one of the country’s biggest commodities: entertainment. In the silent movie era of Hollywood, women wrote, directed and produced, plus there were over twenty independent film companies run by women. That changed when Hollywood became a profitable industry. The absence of women behind the camera affected the women who appeared in front of the lens. Because men controlled the content, they created female characters based on classic archetypes: the good girl and the fallen woman, the virgin and the whore. The women’s movement helped loosen some barriers in Hollywood. A few women, like 20th century Fox President Sherry Lansing, were able to rise to the top. Especially in television, where the financial stakes were lower and advertisers eager to court female viewers, strong female characters began to emerge. Premium cable channels like HBO and Showtime allowed edgy shows like Sex in the City and Girls , which dealt frankly with sex from a woman’s perspective, to thrive. One way women were able to gain clout was to use their stardom to become producers, like Jane Fonda, who had a breakout hit when she produced 9 to 5 . But despite the fact that 9 to 5 was a smash hit that appealed to broad audiences, it was still viewed as a “chick flick”. In Hollywood, movies like Bridesmaids and The Hunger Games , with strong female characters at their center and strong women behind the scenes, have indisputably proven that women centered content can be big at the box office. -

Florida Southern College Assessing the Vanishing Lesbian in Book-To

Florida Southern College Assessing the Vanishing Lesbian in Book-to-Film Adaptations: A Critical Study of Rebecca, Fried Green Tomatoes, and Black Panther Felicia Coursen Thesis Advisor: Dr. Moffitt May 2, 2021 Coursen 2 A Framework for Understanding the Vanishing Lesbian Popular media consistently disregards lesbian voices and identities. The film industry, as a facet of popular media, often neglects to tell lesbian stories. When films do include lesbian characters, the depictions are often problematic and grounded in stereotypes. Literary critic and queer theorist Terry Castle argues the following in her book, The Apparitional Lesbian: Female Homosexuality and Modern Culture: “The lesbian remains a kind of ‘ghost effect’ in the cinema world of modern life: elusive, vaporous, difficult to spot – even when she is there, in plain view, mortal and magnificent, at the center of the screen. Some may even deny she exists at all” (2). Castle explains the “ghost effect” of lesbian characters in cinema, which is better identified as the process of lesbian erasure. Although the two terms are synonymous, “lesbian erasure” provides a more clear-cut verbalization of this process (i.e., there once were lesbian characters, but they are now erased). Lesbian erasure is a direct result of the following: (1) the absence of lesbian characters, (2) the inclusion of only one-dimensional/stereotyped lesbian representation, and/or (3) the use of subversion and subtextualization to hide lesbian characters from audiences. Book-to-film adaptations reveal the ghost effect most clearly. Lesbians in book-to-film adaptations are not only apparitional; they vanish right before the viewers’ eyes. -

Inequality in 900 Popular Films: Gender, Race/Ethnicity, LGBT, & Disability from 2007‐2016

July 2017 INEQUALITY IN POPULAR FILMS MEDIA, DIVERSITY, & SOCIAL CHANGE INITIATIVE USC ANNENBERG MDSCInitiative Facebook.com/MDSCInitiative THE NEEDLE IS NOT MOVING ON SCREEN FOR FEMALES IN FILM Prevalence of female speaking characters across 900 films, in percentages Percentage of 900 films with 32.8 32.8 Balanced Casts 12% 29.9 30.3 31.4 31.4 28.4 29.2 28.1 Ratio of males to females 2.3 : 1 Total number of ‘ ‘ ‘ ‘ ‘ ‘ ‘ ‘ ‘ speaking characters 39,788 LEADING LADIES RARELY DRIVE THE ACTION IN FILM Of the 100 top films in 2016... And of those Leads and Co Leads*... Female actors were from underrepresented racial / ethnic groups Depicted a 3 Female Lead or (identical to 2015) Co Lead 34 Female actors were at least 45 years of age or older 8 (compared to 5 in 2015) 32 films depicted a female lead or co lead in 2015. *Excludes films w/ensemble casts GENDER & FILM GENRE: FUN AND FAST ARE NOT FEMALE ACTION ANDOR ANIMATION COMEDY ADVENTURE 40.8 36 36 30.7 30.8 23.3 23.4 20 20.9 ‘ ‘ ‘ ‘ ‘ ‘ ‘ ‘ ‘ % OF FEMALE SPEAKING % OF FEMALE SPEAKING % OF FEMALE SPEAKING CHARACTERS CHARACTERS CHARACTERS © DR. STACY L. SMITH GRAPHICS: PATRICIA LAPADULA PAGE THE SEXY STEREOTYPE PLAGUES SOME FEMALES IN FILM Top Films of 2016 13-20 yr old 25.9% 25.6% females are just as likely as 21-39 yr old females to be shown in sexy attire 10.7% 9.2% with some nudity, and 5.7% 3.2% MALES referenced as attractive. FEMALES SEXY ATTIRE SOME NUDITY ATTRACTIVE HOLLYWOOD IS STILL SO WHITE WHITE .% percentage of under- represented characters: 29.2% BLACK .% films have NO Black or African American speaking characters HISPANIC .% 25 OTHER % films have NO Latino speaking characters ASIAN .% 54 films have NO Asian speaking *The percentages of Black, Hispanic, Asian, and Other characters characters have not changed since 2007. -

Reclaiming Women's Agency in Swedish Film History And

chapter 1 Visible absence, invisible presence Feminist film history, the database, and the archive Eirik Frisvold Hanssen In this essay I aim to address a series of theoretical and methodological questions relating to current projects that disseminate film historical research focusing on women’s contributions, and in particular the role of the film archive in these efforts. Although the argument is of a general nature, it is nonetheless informed by specific circum- stances. The essay was written in conjunction with the National Library of Norway’s involvement in a specific project—the website, Nordic Women in Film, initiated by the Swedish Film Institute, and linked to the research project ‘Women’s Film History Network: Norden’ (2016–2017).1 In a newspaper commentary on the launch of the Norwegian content published on Nordic Women in Film in December 2017, film scholar Johanne Kielland Servoll described the website as a kind of ‘awareness project’ (erkjennelsesprosjekt) similar to the logic of counting within discourses on gender equality or the Bechdel–Wallace test, revealing how many—or how few—women who have worked behind the camera in Norwegian film history.2 At time of writing, the website includes biographies and filmographies relating to 295 Norwegian women working in the film industry, along with 45 in-depth articles and interviews covering a variety of Norwegian angles on historical periods, professions, and film genres. 33 locating women’s agency in the archive Contributing material to be published on the website entailed a number of choices and questions for the National Library of Norway, some of which I will examine more thoroughly in what follows. -

Representations of Mental Illness in Women in Post-Classical Hollywood

FRAMING FEMININITY AS INSANITY: REPRESENTATIONS OF MENTAL ILLNESS IN WOMEN IN POST-CLASSICAL HOLLYWOOD Kelly Kretschmar, B.A. Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2007 APPROVED: Harry M. Benshoff, Major Professor Sandra Larke-Walsh, Committee Member Debra Mollen, Committee Member Ben Levin, Program Coordinator Alan B. Albarran, Chair of the Department of Radio, Television and Film Sandra L. Terrell, Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Kretschmar, Kelly, Framing Femininity as Insanity: Representations of Mental Illness in Women in Post-Classical Hollywood. Master of Arts (Radio, Television, and Film), May 2007, 94 pp., references, 69 titles. From the socially conservative 1950s to the permissive 1970s, this project explores the ways in which insanity in women has been linked to their femininity and the expression or repression of their sexuality. An analysis of films from Hollywood’s post-classical period (The Three Faces of Eve (1957), Lizzie (1957), Lilith (1964), Repulsion (1965), Images (1972) and 3 Women (1977)) demonstrates the societal tendency to label a woman’s behavior as mad when it does not fit within the patriarchal mold of how a woman should behave. In addition to discussing the social changes and diagnostic trends in the mental health profession that define “appropriate” female behavior, each chapter also traces how the decline of the studio system and rise of the individual filmmaker impacted the films’ ideologies with regard to mental illness and femininity. Copyright 2007 by Kelly Kretschmar ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Chapter 1. INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................... 1 Historical Perspective ........................................................................ 5 Women and Mental Illness in Classical Hollywood ............................... -

Representation of Lesbian Images in Films

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1-1-2003 Women in the dark: representation of lesbian images in films Hye-Jin Lee Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Recommended Citation Lee, Hye-Jin, "Women in the dark: representation of lesbian images in films" (2003). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 19470. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/19470 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. women in the dark: Representation of lesbian images in films by Hye-Jin Lee A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Major: Journalism and Mass Communication Program of Study Committee: Tracey Owens Patton, Major Professor Jill Bystydzienski Cindy Christen Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2003 11 Graduate College Iowa State University This is to certify that the master's thesis of Hye-Jin Lee has met the thesis requirement of Iowa State University Signatures have been redacted for privacy 111 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS iv ABSTRACT v INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER 1: REVIEW OF LITERATURE The Importance of Studying Films 4 Homosexuality and -

American Artscape, No 1, 2020

Number 2, 2020 Celebrating the Centennial of Women’s Suffrage 1 Honoring Their Voices StageOne Family Theatre's This issue Production of Lawbreakers! BY REBECCA SUTTON In honor of the centennial of women’s suffrage, the National Endowment for the Arts is celebrating NATIONAL COUNCIL the many ways the arts have empowered and elevated ON THE ARTS women, as well as the many ways that women artists 4 Mary Anne Carter, have shaped and elevated American art. As part Chairman The Goddess of Moving of the agency’s commemoration of this event, we Pictures encouraged applicants for fiscal year 2020 grants to Bruce Carter Aaron Dworkin Barnard College's Athena submit funding requests for projects that celebrated Lee Greenwood women’s suffrage and equality. We are featuring a Film Festival Elevates Women Deepa Gupta in Film number of those projects in this issue of American Paul W. Hodes BY MICHAEL GALLANT Artscape, ranging from a festival that highlights the Maria Rosario Jackson creativity of women filmmakers to a play for young Emil Kang audiences that outlines the history of the suffrage Charlotte Kessler movement. María López De León Rick Lowe 8 As part of our commemorative efforts, we have David “Mas” Masumoto also published a book highlighting the role that Barbara Ernst Prey Creativity and the arts played in the suffrage movement, and Ranee Ramaswamy Persistence ultimately, in the successful passage of the 19th Tom Rothman Art that Fueled the Fight for amendment—an excerpt from that book is included Olga Viso Women's Suffrage in this issue. We are also encouraging federal AN EXCERPT agencies and arts organizations across the country EX-OFFICIO to light up public buildings and landmarks in purple Sen. -

Gender Equality Report?

Production: Swedish Film Institute Editors: Sara Karlsson and Jenny Wikstrand Production Manager: Ida Kjellgren Illustrations, cover and insert: Siri Carlén Translation: Matt Bibby Innehåll A comment from the CEO ................................................................................................................... 4 Anna Serner ............................................................................................................................................. 4 Foreword ................................................................................................................................................ 5 Why a Gender Equality Report? ......................................................................................................... 7 The emergence of gender equality in Sweden ................................................................................ 9 Rebellion the best cure for obdurate structures? ........................................................................... 11 Women’s demands and government equality measures ......................................................... 12 Obdurate structures and lower priority ........................................................................................ 13 Radical interpretations and unruly women ................................................................................. 14 A modified commission ...................................................................................................................... 16 Our view of the -

Classical Hollywood Film Directors' Female-As-Object Obsession and Female Directors' Cinematic Response: a Deconstructionist Study of Six Films

California State University, San Bernardino CSUSB ScholarWorks Theses Digitization Project John M. Pfau Library 1996 Classical Hollywood film directors' female-as-object obsession and female directors' cinematic response: A deconstructionist study of six films Sharon Jeanette Chapman Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons Recommended Citation Chapman, Sharon Jeanette, "Classical Hollywood film directors' female-as-object obsession and female directors' cinematic response: A deconstructionist study of six films" (1996). Theses Digitization Project. 1258. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project/1258 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the John M. Pfau Library at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses Digitization Project by an authorized administrator of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CliASSICAL HOLLYWOOD FILM DIRECTORS' FEMALE-AS-OBJECT OBSESSION AND FEMALE DIRECTORS' CINEMATIC RESPONSE; A DECONSTRUCTIONIST STUDY OF SIX FILMS A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in English Composition by Sharon Jeanette Chapman September 1996 CLASSICAL HOLLYWOOD FILM DIRECTORS' FEMALE-AS-OBJECT OBSESSION AND FEMALE DIRECTORS' CINEMATIC RESPONSE: A DECONSTRUCTIONIST STUDY OF SIX FILMS A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino by Sharon Jeanette Chapman September 1996 Approved by: Dr. Bruce Golden, Chair, English Date Kellie Raybuirn Dr. e Pigeon ABSTRACT My thesis consists of a short study of the theoretical backgrounds of feminist film study and Classic Hollywood norms and paradigms to prepare the reader for six readings—Singin' in the Rain, Rebecca and Touch of Evil from the Classic male-directed canon; and Fast Times at Ridgemont High, Desperately Seeking Susan, and Home for the Holidays directed by women. -

Sketchy Lesbians: "Carol" As History and Fantasy

Swarthmore College Works Film & Media Studies Faculty Works Film & Media Studies Winter 2015 Sketchy Lesbians: "Carol" as History and Fantasy Patricia White Swarthmore College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://works.swarthmore.edu/fac-film-media Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons Recommended Citation Patricia White. (2015). "Sketchy Lesbians: "Carol" as History and Fantasy". Film Quarterly. Volume 69, Issue 2. 8-18. DOI: 10.1525/FQ.2015.69.2.8 https://works.swarthmore.edu/fac-film-media/52 This work is brought to you for free by Swarthmore College Libraries' Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Film & Media Studies Faculty Works by an authorized administrator of Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FEATURES SKETCHY LESBIANS: CAROL AS HISTORY AND FANTASY Patricia White Lesbians and Patricia Highsmith fans who savored her 1952 Headlining a film with two women is considered box of- novel The Price of Salt over the years may well have had, like fice bravery in an industry that is only now being called out me, no clue what the title meant. The book’s authorship was for the lack of opportunity women find both in front of and also murky, since Highsmith had used the pseudonym Claire behind the camera. The film’s British producer Liz Karlsen, Morgan. But these equivocations only made the book’s currently head of Women in Film and Television UK, is out- lesbian content more alluring. When published as a pocket- spoken about these inequities. Distributor Harvey Weinstein sized paperback in 1952, the novel sold nearly one million took on the risk in this case, banking on awards capital to copies, according to Highsmith, joining other suggestive counter any lack of blockbuster appeal. -

Women in Independent Film, 2016-17

Women in Independent Film, 2016-17 Center for the Study of Women in Television & Film, San Diego State University Dr. Martha M. Lauzen May 2017 Key Findings •High profile film festivals in the U.S. •Women are more likely to direct screened three times as many narrative documentaries than narrative features. films directed by men as by women in Women accounted for 33% of directors 2016-17. The 23 festivals considered in on documentaries versus 25% of this study screened an average of 6 directors on narrative features. narrative films directed by at least one woman compared with an average of 18 •Films with at least one woman director features directed by men. also had substantially higher percentages of women writers, editors, •U.S. festivals screened almost twice as and cinematographers. On films with at many documentaries directed by men as least one female director, women by women in 2016-17. The festivals in comprised 74% of writers vs. 7% on this study screened an average of 7 films directed exclusively by men. On documentaries directed by at least one films with women directors, women woman compared with an average of 13 accounted for 36% of editors compared directed by men. with 17% on films directed exclusively by men. On films with women directors, •Overall, independent films screened at women comprised 23% of high profile film festivals in the U.S. cinematographers versus 6% on films employed more than twice as many men directed exclusively by men. as women in key behind-the-scenes roles in 2016-17. 72% of those working Method in these roles were males and 28% were females.