The Antitrust Roadblock: Preventing Consolidation of the Craft Beer Market Aric Codog

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Deity's Beer List.Xls

Page 1 The Deity's Beer List.xls 1 #9 Not Quite Pale Ale Magic Hat Brewing Co Burlington, VT 2 1837 Unibroue Chambly,QC 7% 3 10th Anniversary Ale Granville Island Brewing Co. Vancouver,BC 5.5% 4 1664 de Kronenbourg Kronenbourg Brasseries Stasbourg,France 6% 5 16th Avenue Pilsner Big River Grille & Brewing Works Nashville, TN 6 1889 Lager Walkerville Brewing Co Windsor 5% 7 1892 Traditional Ale Quidi Vidi Brewing St. John,NF 5% 8 3 Monts St.Syvestre Cappel,France 8% 9 3 Peat Wheat Beer Hops Brewery Scottsdale, AZ 10 32 Inning Ale Uno Pizzeria Chicago 11 3C Extreme Double IPA Nodding Head Brewery Philadelphia, Pa. 12 46'er IPA Lake Placid Pub & Brewery Plattsburg , NY 13 55 Lager Beer Northern Breweries Ltd Sault Ste.Marie,ON 5% 14 60 Minute IPA Dogfishhead Brewing Lewes, DE 15 700 Level Beer Nodding Head Brewery Philadelphia, Pa. 16 8.6 Speciaal Bier BierBrouwerij Lieshout Statiegeld, Holland 8.6% 17 80 Shilling Ale Caledonian Brewing Edinburgh, Scotland 18 90 Minute IPA Dogfishhead Brewing Lewes, DE 19 Abbaye de Bonne-Esperance Brasserie Lefebvre SA Quenast,Belgium 8.3% 20 Abbaye de Leffe S.A. Interbrew Brussels, Belgium 6.5% 21 Abbaye de Leffe Blonde S.A. Interbrew Brussels, Belgium 6.6% 22 AbBIBCbKE Lvivske Premium Lager Lvivska Brewery, Ukraine 5.2% 23 Acadian Pilsener Acadian Brewing Co. LLC New Orleans, LA 24 Acme Brown Ale North Coast Brewing Co. Fort Bragg, CA 25 Actien~Alt-Dortmunder Actien Brauerei Dortmund,Germany 5.6% 26 Adnam's Bitter Sole Bay Brewery Southwold UK 27 Adnams Suffolk Strong Bitter (SSB) Sole Bay Brewery Southwold UK 28 Aecht Ochlenferla Rauchbier Brauerei Heller Bamberg Bamberg, Germany 4.5% 29 Aegean Hellas Beer Atalanti Brewery Atalanti,Greece 4.8% 30 Affligem Dobbel Abbey Ale N.V. -

Half Wall Menu Beer

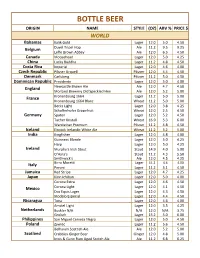

BOTTLE BEER ORIGIN NAME STYLE (OZ) ABV % PRICE $ WORLD Bahamas Kalik Gold Lager 12.0 5.0 4.50 Belgium Duvel Tripel Hop Ale 11.2 9.5 9.25 Leffe Brown Abbey Ale 12.0 6.5 4.50 Canada Moosehead Lager 12.0 5.0 4.25 China Lucky Buddha Lager 11.2 4.8 4.50 Costa Rica Imperial Lager 12.0 4.6 4.00 Czech Republic Pilsner Urquell Pilsner 12.0 4.4 4.50 Denmark Carlsberg Pilsner 11.2 5.0 4.50 Dominican Republic Presidente Lager 12.0 5.0 4.00 England Newcastle Brown Ale Ale 12.0 4.7 4.50 Morland Brewery Old Speckled Hen Ale 12.0 5.2 5.00 France Kronenbourg 1664 Lager 11.2 5.0 5.00 Kronenbourg 1664 Blanc Wheat 11.2 5.0 5.00 Becks Light Lager 12.0 3.8 4.25 Schofferhofer Grapefruit Wheat 12.0 2.5 4.50 Germany Spaten Lager 12.0 5.2 4.50 Tucher Kristall Wheat 16.9 5.3 6.00 Warsteiner Premium Pilsner 11.2 4.8 4.50 Iceland Einstok Icelandic White Ale Wheat 11.2 5.2 5.00 India Kingfisher Lager 12.0 4.8 4.00 Guinness Blonde Lager 12.0 5.0 4.25 Harp Lager 12.0 5.0 4.25 Ireland Murphy's Irish Stout Stout 14.9 4.0 5.00 O'Hara's Stout 11.2 4.3 5.50 Smithwick's Ale 12.0 4.5 4.25 Italy Birra Moretti Lager 11.2 4.6 4.00 Peroni Lager 11.2 5.1 4.50 Jamaica Red Stripe Lager 12.0 4.7 4.25 Japan Kirin Ichiban Lager 12.0 5.0 4.00 Corona EXtra Lager 12.0 4.6 4.50 Mexico Corona Light Lager 12.0 4.1 4.50 Dos Equis Lager Lager 12.0 4.3 4.50 Modelo Especial Lager 12.0 4.4 4.50 Nicaragua Tona Lager 12.0 4.6 4.00 Amstel Light Lager 12.0 3.5 4.25 Netherlands Buckler N/A N/A 12.0 N/A 3.75 Grolsch Lager 15.2 5.0 6.00 Philippines San Miguel Cerveza Negra Lager 12.0 5.0 4.50 Poland -

BEER SELECTION Lagers and Pilsners Are Fermented and Stored (‘Lagered’) at Cooler Tempatures

LOCAL BREWING COMPANY WWW.lbCPALMHARBOR.COM BEER SELECTION Lagers and Pilsners are fermented and stored (‘lagered’) at cooler tempatures. Clean, crisp, low fruitiness. Toasted Lager (Blue Point Brewing Co) 5.5% Long Island, NY $6 Bud Light (Anheuser-Busch, Inc) 4.2% St. Louis, Mo $3.75 Budweiser (Anheuser-Busch, Inc) 5% St. Louis, Mo $3.75 Coors Light (Coors Brewing Co) 4% Golden, Co $3.75 LAGER/PILSNER Helicity Pils (Big Storm Brewery Co) 4.3% Odessa, Fl $4.75 Pirata Pils (Dawrin Brewing Co) 4.9% Bradenton, Fl $6.50 Longboard Island (Kona Brewing Co) 4.6% Hawaii $6 Lager Ultra (Anheuser-Busch, Inc) 4.2% St. Louis, Mo $4 Miller Lite (Miller Brewing Co) 4% Milwaukee, WI $3.75 V-Twin (Motorworks Co) 4.7% Bradenton, Fl $6.25 Stella Artois (Stella Artois) 4.5% Europe $6 Yuengling (Yuengling Brewery) 4% Pottsville, PA $4.25 Traditional Lager A lager that is richly malty, often with toasty notes, and generally a higher alcohol level than other lager beers. BOCK Amber Bock (Anheuser-Busch, Inc.) 5.2% St.Louis, Mo $3.75 (Rogue Ales/Oregon 7% Ashland, OR Dead Guy Ale Brewery Co) $7 Hybrid beers mix lager and ale techniques like Steam beer, a warmer fermented lager. Beach Blonde Ale (3 Daughters Brewing) 5% St. Petersburg, Fl $6.50 HYBRID Poolside Kolseh (JDubs Brewing) 5% Sarasota, Fl $6 Big Wave Golden Ale (Kona Brewing Co) 4.4% Hawaii $6 English style ales are typical pub ‘bitters’ (like ESB) and brown session ales with malt and often caramel and fruity notes and floral or earthy English hops. -

It's Free to Join the Club!

BOTTLES OF BEER 99 ON THE WALL IT’S FREE TO JOIN THE CLUB! 50 Beers Tavern Koozie 99 Beers Tavern Mug, Your Official Club Card & Club T-Shirt 500 Beers Name Plate on the 500 Club Plaque 1000 Beers Tavern Logo Leather Jacket Name Plate on the 1000 Club Plaque BEER BREWERY STYLE ABV PRICE 1. 312 Urban Wheat Goose Island Beer Co (Illinois) American Pale Wheat 4.2% 6 2. 60 Minute IPA Dogfish Head Brewery (Delaware) American IPA 6% 7 3. Abita Amber Abita Brewing Co (Louisiana) Vienna Lager 4.5% 6 4. All Day IPA Founders Brewing Co (Michigan) American IPA 4.7% 6 5. Amstel Light Amstel Brouwerij B. V (Amsterdam) Light Lager 3.5% 6 6. Bear Lasers Hidden Springs Ale Works (Tampa FL) American IPA 6.7% 8 7. Becks Brauerei Beck & Co (Germany) German Pilsener Style Beer 5% 6 8. Bells Oberon Ale Bells Brewery Inc (Michigan) American Style Pale Wheat Ale 5.8% 5 9. Bells Two Hearted Ale Bells Brewery Inc. (Michigan) American IPA 7% 6 10. Big Wave Kona Brewing Co (Hawaii) Golden Ale 4.4% 6 11. Boddingtons Pub Ale Boddingtons (England) English Pale Ale 4.7% 6 12. Boomsauce Lord Hobo Brewing Co (Massachusetts) American Double/Imperial IPA 7.8% 10 13. Breakfast Stout Founders Brewing Co (Michigan) Oatmeal Stout 8.3% 8 14. Breckenridge Vanilla Porter Breckenridge Brewery (Colorado) American Porter 5.4% 6 15. Brewer’s Day Off D9 Brewing Company (North Carolina) Sour Gose 4.8% 9 16. Bud Light Lime Anheuser-Busch (Missouri) Light Lager 4.2% 5 17. -

Bt-104 Report -- Beer Shipped Into Wisconsin Returns Posted Between 6/1/2021 and 6/30/2021

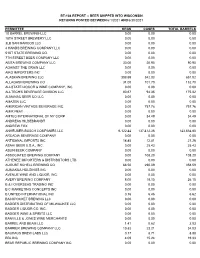

BT-104 REPORT -- BEER SHIPPED INTO WISCONSIN RETURNS POSTED BETWEEN 6/1/2021 AND 6/30/2021 PERMITTEE KEGS CASES TOTAL BARRELS 10 BARREL BREWING LLC 0.00 0.00 0.00 18TH STREET BREWERY LLC 0.00 0.00 0.00 3LB SAN MARCOS LLC 0.00 0.00 0.00 4 HANDS BREWING COMPANY LLC 0.00 0.00 0.00 51ST STATE BREWING CO. 0.00 0.00 0.00 7TH STREET BEER COMPANY LLC 0.00 0.00 0.00 ABITA BREWING COMPANY LLC 30.00 20.90 50.90 AGAINST THE GRAIN LLC 0.00 0.00 0.00 AIKO IMPORTERS INC 0.00 0.00 0.00 ALASKAN BREWING LLC 308.99 342.03 651.02 ALLAGASH BREWING CO 31.00 101.70 132.70 ALLSTATE LIQUOR & WINE COMPANY, INC. 0.00 0.00 0.00 ALLTECH'S BEVERAGE DIVISION LLC 80.67 94.35 175.02 ALMANAC BEER CO LLC 0.00 0.00 0.00 AMAZEN LLC 0.00 0.00 0.00 AMERICAN VINTAGE BEVERAGE INC. 0.00 757.76 757.76 AMIR PEAY 0.00 0.00 0.00 AMTEC INTERNATIONAL OF NY CORP 0.00 34.49 34.49 ANDREAS HILDEBRANDT 0.00 0.00 0.00 ANDREW FOX 0.00 0.00 0.00 ANHEUSER-BUSCH COMPANIES LLC 6,122.44 137,412.36 143,534.80 ARCADIA BEVERAGE COMPANY 0.00 0.00 0.00 ARTISANAL IMPORTS INC 14.45 12.81 27.26 ASAHI BEER U.S.A., INC. 0.00 25.43 25.43 ASLIN BEER COMPANY 0.00 0.00 0.00 ASSOCIATED BREWING COMPANY 0.00 108.20 108.20 ATHENEE IMPORTERS & DISTRIBUTORS LTD 0.00 0.00 0.00 AUGUST SCHELL BREWING CO 68.50 290.09 358.59 AUMAKUA HOLDINGS INC 0.00 0.00 0.00 AVENUE WINE AND LIQUOR, INC. -

MASTER BEER LIST BOOTH BREWERY/BEER A6 903 Brewers 903 Chosen One Coconut Ale 903 Crackin' up 903 I So Pale Ale 903 Sasquatch Chocolate Milk Stout

#BTBF2014 - MASTER BEER LIST BOOTH BREWERY/BEER A6 903 Brewers 903 Chosen One Coconut Ale 903 Crackin' Up 903 I So Pale Ale 903 Sasquatch Chocolate Milk Stout E2 Abita Brewing Company Abita Amber Lager Abita Andygator Abita Purple Haze Abita Strawberry Harvest Lager F7 Ace Cider Ace Berry Cider Ace Joker Dry Hard Cider Ace Pear Cider L6 Adelbert's Brewery Adelbert's Black Rhino Adelbert's Dancin' Monks Adelbert's Philosophizer Adelbert's The Traveler J2 Alaskan Brewing Company Alaskan Hopothermia Double IPA Alaskan Amber Alaskan ESB Alaskan Pilot Series: Jalapeño Imperial IPA** D8 Armadillo Ale Works Armadillo Ale Works Brunch Money Armadillo Ale Works Greenbelt Farmhouse Ale Armadillo Ale Works Quakertown Stout J9 Asahi Beer USA Asahi Super Dry Asahi Black (Kuronama) Asahi Brewmasters Select F9 Ballast Point Brewing Company Ballast Point Calico Amber Ale Ballast Point Piper Down Scottish Ale Ballast Point Sculpin IPA Ballast Point Victory at Sea WALL Ben E. Keith Tap Wall Alaskan Taku River Red Dogfish Head Burton Baton Flying Dog Raging Bitch Founders Curmudgeon Old Ale Great Divide Espresso Oak Aged Yeti Imperial Stout* Green Flash Palate Wrecker Lagunitas Cappuccino Stout Oskar Blues IceyPA Real Ale Sisyphus Saint Arnold Icon Blue - Brown Porter Uinta Crooked Line Labyrinth Black Ale Victory Hop Ranch Imperial India Pale Ale Alaskan Smoked Porter* Great Divide Hoss Rye Lager* Harpoon Black Forest* Ommegang Glimmerglass Saison* Sierra Nevada Harvest Single Hop IPA Yakima #291* Uinta Crooked Line Cockeyed Cooper* * Alternates to be tapped, as available F8 Big Sky Brewing List unavailable at time of publishing F10 Blue Moon Brewing Co. -

Beverages Iced Tea - 1.25 Lemonade - 1.25 Flavored Lemonade - 1.75

Catering Bar Service - Bar Menu - Food Truck All prices are per guest. Open Bar Beer | Wine | Soda 2 hours - 10 3 domestic beers, 3 hours - 12 1 specialty/craft beer, 4 hours - 14 3 house wines 5 hours - 16 Open House Bar liquor | Beer | Wine | Soda 2 hours - 12 3 domestic beers, 1 specialty/craft beer, 3 hours - 14 3 house wines, well liquor (rum, gin, 4 hours - 16 vodka, tequila, bourbon, scotch), mixers 5 hours - 18 Open Premium Bar liquor | Beer | Wine | Soda 3 domestic beers, 1 specialty/craft beer, 3 house 2 hours - 14 wines, premium liquor (Bacardi Light rum, Tangueray 3 hours - 16 gin, Grey Goose vodka, Jose Cuervo tequila, Jack 4 hours - 18 Daniels bourbon, Johnnie Walker Black scotch), mixers 5 hours - 20 SCoocfat- CDolar pirnokdus ct&s J| Juuiiccee 2 hours - 3 3 hours - 4 Coke, Diet Coke, Sprite, orange 4 hours - 5 juice, apple juice, cranberry juice 5 hours - 6 Additional Beverages Iced Tea - 1.25 Lemonade - 1.25 Flavored lemonade - 1.75 Signature/specialty drinks/champagne toast available for an additional fee. Disposable drinkware, ice, garnish, straws & beverage napkins included. Prices do not include sales tax & service fee. Prices subject to change. Gratuity not included, but always appreciated! Graze LLC | 409 E Osage Street | Pacific, MO 63069 | [email protected] | www.tasteofgraze.com January 2020 - Prices Subject to Change Catering Bar Service - Bar Menu - Food Truck Wine, & beer selections. Beer Selections - Domestic - - CRAFT - Budweiser, Bud Light Goose Island, Shock Top Bud Select, Bud Ice Kona, Blue Point Busch, Natural Light Red Hook Michelob, Michelob Ultra Widmer Brothers Michelob Ultra Pure Gold Virtue Cider Michelob Golden Light 10 Barrel Brewing Co. -

Beer Keg Price List

“We are the Party Specialist” Valley Liquor Keg Sheet 306 E. MAIN STREET PHONE: (920) 788-3214 EMAIL:[email protected] ITTLE HUTE AX EBSITE L C , WI 54140 F : (920) 788-3262 W : VALLEYLIQUORLITTLECHUTE.COM 21 Kegs Valley Liquor Purchases from: Wisconsin Distributors RiverWisconsin City Distributing Distributors Domestic Breckenridge Brewery—Littleton, Colorado Budweiser ½ BBL $159.95 Christmas Ale ½ BBL—Winter Warmer, 7.1% $189.95 Budweiser ¼ BBL $83.95 Vanilla Porter ½ BBL—American Porter, 5.4% $189.95 Budweiser ⅙ BBL $69.95 Christmas Ale ⅙ BBL—Winter Warmer, 7.1% $99.95 Bud Light ½ BBL $159.95 Vanilla Porter ⅙ BBL—American Porter, 5.4% $99.95 Bud Light ¼ BBL $83.95 Avalanche Amber Ale ½ BBL—American Amber, 5% $189.95 Michelob Ultra ½ BBL $159.95 Oktoberfest ½ BBL—Marzen/Oktoberfest, 6% $189.95 Michelob Ultra ⅙ BBL $69.95 Strawberry Sky ½ BBL—German Kolsch, 4.8% $189.95 Michelob Amber Bock ½ BBL $159.95 Agave Wheat ⅙ BBL—Herb/Spiced Beer, 4.2% $99.95 Michelob Amber Bock ⅙ BBL $69.95 Autumn Ale ⅙ BBL—English Old Ale, 7% $99.95 Land Shark ⅙ BBL $74.95 Avalanche Amber Ale ⅙ BBL—American Amber, 5% $99.95 Busch Light ½ BBL $149.95 Hop Peak IPA ⅙ BBL—American IPA, 6.5% $109.95 Natural Light ½ BBL $94.95 Resolution ⅙ BBL—Fruit & Field Beer, 3.5% $99.95 Budweiser Copper Lager ⅙ BBL $69.95 Strawberry Sky ⅙ BBL—German Kolsch, 4.8% $99.95 Budweiser Discovery Reserve ⅙ BBL $69.95 Summer Pils ⅙ BBL—German Pilsner, 5% $99.95 Budweiser Freedom Reserve ⅙ BBL $69.95 Coffee Stout ½ BBL—American Stout, 4.5% $199.95 Budweiser Nitro Reserve ½ BBL $159.95 -

Top 50 Brewers of 2015

TOP 50 BREWERS OF 2015 Top 50 U.S. Craft Brewing Companies (Based on 2015 beer sales volume) RANK BREWING COMPANY CITY, STATE RANK BREWING COMPANY CITY, STATE 1 D. G. Yuengling and Son, Inc Pottsville, PA 26 Victory Brewing Co Downingtown, PA 2 Boston Beer Co Boston, MA 27 August Schell Brewing Co New Ulm, MN 3 Sierra Nevada Brewing Co Chico, CA 28 Long Trail Brewing Co Bridgewater Corners, VT 4 New Belgium Brewing Co Fort Collins, CO 29 Summit Brewing Co Saint Paul, MN 5 Gambrinus San Antonio, TX 30 Shipyard Brewing Co Portland, ME 6 Lagunitas Brewing Co* Petaluma, CA 31 Full Sail Brewing Co Hood River, OR 7 Bell’s Brewery, Inc Kalamazoo, MI 32 Odell Brewing Co Fort Collins, CO 8 Deschutes Brewery Bend, OR 33 Southern Tier Brewing Co Lakewood, NY 9 Minhas Craft Brewery Monroe, WI 34 Rogue Ales Brewery Newport, OR 10 Stone Brewing Co Escondido, CA 35 21st Amendment Brewery Bay Area, CA 11 Ballast Point Brewing & Spirits* San Diego, CA 36 Ninkasi Brewing Co Eugene, OR 12 Brooklyn Brewery Brooklyn, NY 37 Flying Dog Brewery Frederick, MD 13 Firestone Walker Brewing Co Paso Robles, CA 38 Narragansett Brewing Co Providence, RI 14 Oskar Blues Brewing Holding Co Longmont, CO 39 Left Hand Brewing Co Longmont, CO 15 Duvel Moortgat USA Kansas City, MO/ 40 Uinta Brewing Co Salt Lake City, UT Cooperstown, NY 41 Green Flash Brewing Co San Diego, CA 16 Dogfish Head Craft Brewery Milton, DE 42 Allagash Brewing Co Portland, ME 17 Matt Brewing Co Utica, NY 43 Lost Coast Brewery Eureka, CA 18 SweetWater Brewing Co Atlanta, GA 44 Bear Republic Brewing Co -

1991 Great American Beer Festival Winners List

1991 Great American Beer Festival Winners List STYLE CATEGORY AWARD WINNING BEER COMPANY Amber Ale/American Pale Ales Gold Alaskan Autumn Ale Alaskan Brewing Amber Ale/American Pale Ales Silver Seabright Amber Ale Seabright Brewery Inc Amber Ale/American Pale Ales Bronze 90 Shilling Ale Odell Brewing Co Amber/Viennas Gold Adler Brau Amber Appleton Brewing Co/Adler Brau Amber/Viennas Silver Schild Brau Amber Millstream Brewing Co Amber/Viennas Bronze Stein Beer Lakefront Brewery Inc American Brown Ales Gold Tied House Dark Redwood Coast Brewing Co Hubcap Brewery & Kitchen - American Brown Ales Silver Beaver Tail Brown Ale Dallas American Brown Ales Bronze Santa Fe Nut Brown Ale Santa Fe Brewing Company American Dry Lagers Gold Coors Dry Coors Brewing Co American Dry Lagers Silver Michelob Dry Anheuser-Busch Companies Inc American Dry Lagers Bronze Stoney's Extra Dry Jones Brewing Co American Lager-Ales Gold Genesee Cream Ale Genesee/High Falls Brewing American Lager-Ales Silver Northern Light Long Trail Brewing Co American Lagers Gold Pearl Lager Beer Pabst Brewing Co American Lagers Silver Stoney's Beer Jones Brewing Co American Lagers Bronze Keystone Light Coors Brewing Co American Light Lagers Gold Keystone Light Coors Brewing Co American Light Lagers Silver Stoney's Light Jones Brewing Co American Light Lagers Bronze Bud Light Anheuser-Busch Companies Inc American Malt Liquors Gold Old English 800 Pabst Brewing Co Hudepohl-Schoenling Brewing American Malt Liquors Silver Big Jug Xtra Malt Liquor Co American Malt Liquors Bronze King Cobra -

Draft Beer Cans

DRAFT BEER CANS PABST BLUE RIBBON pint $4.00 FRULI 10oz $7.25 ODELL IPA pint $5.50 MILLER LITE $4.50 American Adjunct Lager ABV 4.74% crowler $6.40 Strawberry Fruit Beer ABV 4.1% crowler $16.80 American India Pale Ale ABV 7.2% crowler $8.80 Light Lager ABV 4.17% Pabst Brewing Co., Los Angeles, CA Brouwerij Huyghe, Melle, Belgium Odell Brewing Co., Ft. Collins, CO Miller Brewing, Milwaukee, WI HELL pint $5.25 WICK FOR BRAINS pint $5.50 HOP 80 10oz $6.50 PABST BLUE RIBBON $4.00 Munich Helles Lager ABV 4.5% crowler $8.40 Pumkin Ale ABV 5.4% crowler $8.80 American India Pale Ale ABV 6.5% crowler $15.60 American Adjunct Lager ABV 4.74% Surly Brewing Co, Brooklyn Center, MN Nebraska Brewing Co., La Vista, NE Knee Deep Brewing Co., Auburn, CA Pabst Brewing Company, Woodridge, IL BLUE MOON pint $5.50 LUMBERJACK (RHUBARB) (GF) 10oz $7.00 MR. WIGGLES DOUBLE DANK 10oz $6.00 TECATE $4.50 Witbier ABV 5.4% crowler $8.80 Hard Cider ABV 6% crowler $16.80 American Imperial IPA ABV 9.2% crowler $14.40 American Adjunct Lager ABV 4.5% Coors Brewing Co., Golden, CO Schilling Cidery, Seattle, WA Rahr & Sons Brewing Co., Ft. Worth, TX Cerveceria Cuauhtémoc Moctezuma, S.A. de C.V., Mexico PINK PEPPERCORN WIT pint $5.50 SNOZZBERRY SOUR 10oz $6.50 BACKSWING BROWN ALE pint $5.50 BRICKWAY HEF $5.00 Hefeweizen Witbier ABV 4.8% crowler $8.80 Sour Ale ABV 5.9% crowler $15.60 English Brown Ale ABV 6.5% crowler $8.80 ABV 5% Pint 9 Brewing Co., Papillion, NE Kinkaider Brewing Co., Broken Bow, NE Backswing Brewing Co., Lincoln, NE Brickway Brewery & Distillery, Omaha, NE FRANZISKANER HEFE-WEISSBIER 20oz $7.25 SUMMER IN THE CITY 10oz $10.00 HELL HATH NO FURY 10oz $7.75 FAT TIRE $5.00 American Amber Ale ABV 5.2% Hefeweizen ABV 5.0% crowler $11.60 American Wild Ale ABV 6.6% crowler $24.00 Dubbel ABV 7.7% crowler $18.60 New Belgium Brewing, Ft. -

Brewers Association Lists Top 50 Breweries of 2013

Brewers Association Lists Top 50 Breweries of 2013 Top 50 U.S. Craft Brewing Companies (Based on 2013 beer sales volume) Rank Brewing Company City State Rank Change 1 Boston Beer Co. Boston MA 0 2 Sierra Nevada Brewing Co. Chico CA 0 3 New Belgium Brewing Co. Fort Collins CO 0 4 Gambrinus San Antonio TX 0 5 Lagunitas Brewing Co. Petaluma CA 1 6 Deschutes Brewery Bend OR -1 7 Bell's Brewery, Inc. Galesburg MI 0 8 Duvel Moortgat USA Kansas City & MO/NY N/A Cooperstown 9 Brooklyn Brewery Brooklyn NY 2 10 Stone Brewing Co. Escondido CA 0 11 Matt Brewing Co. Utica NY -3 12 Harpoon Brewery Boston MA -3 13 Dogfish Head Craft Brewery Milton DE 0 14 Shipyard Brewing Co. Portland ME 1 15 Abita Brewing Co. Abita Springs LA -1 16 Firestone Walker Brewing Co. Paso Robles CA 4 17 Alaskan Brewing Co. Juneau AK -1 18 New Glarus Brewing Co. New Glarus WI -1 19 SweetWater Brewing Co. Atlanta GA 5 20 Great Lakes Brewing Co. Cleveland OH -1 21 Anchor Brewing Co. San Francisco CA 0 22 Long Trail Brewing Co. Bridgewater Corners VT -4 23 Summit Brewing Co. St. Paul MN 0 24 Oskar Blues Brewery Longmont CO 3 25 Full Sail Brewing Co. Hood River OR -1 26 Founders Brewing Co. Grand Rapids MI 4 27 Rogue Ales Newport OR -5 28 Victory Brewing Co. Downingtown PA -2 29 Ballast Point Brewing Co. San Diego CA 17 30 Ninkasi Brewing Co. Eugene OR 1 Rank Brewing Company City State Rank Change 31 Southern Tier Brewing Co.