Patrick Sellar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Download

520 PROCEEDINGS OF THE SOCIETY, MAY 9, 1904. IV. AN ACCOUN E ABERAOH-MACKATH F TO Y BANNER EXHIBITEW NO , D E NATIONATH N I L MUSEUM REVY B .. MACKAY.A , WESTERDALE MANSE, HALKIKK. The earliest reference to the Aberach-Mackay Banner of which we have any knowledge, meantime, is in the article on Tongue parish in e Firstth Statistical Account, written abou e tEev th 179 . y b 2Wm . Mackenzie, and is as follows :— " There is a cave in tlie rock upon which the Castle [Varrich, near Tongue] is built called Leabuidh Evin Abaruich, i.e. John of Lochaber's bed, whither he is said to have retired in times of danger. A family of Mackays is descended fro mreportee ar him d an , d stil havo t l thein ei r possessio s bannernhi , with the motto wrought in golden letters, Biodh treun—Biodh treun, i.e. Be valiant." The writer of this article was inducted minister of Tongue in 1769, and laboure n thai d t parish s deattilhi l n 1834i h t beforbu ;s hi e settlement at Tongue he was minister at Achness on Strathnaver from 1766 to 1769, as we are informed by his descendant, James Macdonald, Esq., W.S., Edinburgh s lond intimatHi gan . e acquaintance wite th h Mackays both on Strathnaver—where he had a daughter married and settled—and at Tongue, Lord Reay's seat, coupled with his taste for family lore, as we gather from Sage's Memorabilia Domestica, give considerable weight to his passing reference to the Aberach-Mackay banner. -

Come Walk in the Footsteps of Your Ancestors

Come walk in the footsteps of your ancestors Come walk in the footsteps Your Detailed Itinerary of your ancestors Highland in flavour. Dunrobin Castle is Museum is the main heritage centre so-called ‘Battle of the Braes’ a near Golspie, a little further north. The for the area. The scenic spectacle will confrontation between tenants and Day 1 Day 3 largest house in the northern Highlands, entrance you all the way west, then police in 1882, which was eventually to Walk in the footsteps of Scotland’s The A9, the Highland Road, takes you Dunrobin and the Dukes of Sutherland south, for overnight Ullapool. lead to the passing of the Crofters Act monarchs along Edinburgh’s Royal speedily north, with a good choice of are associated with several episodes in in 1886, giving security of tenure to the Mile where historic ‘closes’ – each stopping places on the way, including the Highland Clearances, the forced crofting inhabitants of the north and with their own story – run off the Blair Castle, and Pitlochry, a popular emigration of the native Highland Day 8 west. Re-cross the Skye Bridge and main road like ribs from a backbone. resort in the very centre of Scotland. people for economic reasons. Overnight continue south and east, passing Eilean Between castle and royal palace is a Overnight Inverness. Golspie or Brora area. At Braemore junction, south of Ullapool, Donan Castle, once a Clan Macrae lifetime’s exploration – so make the take the coastal road for Gairloch. This stronghold. Continue through Glen most of your day! Gladstone’s Land, section is known as ‘Destitution Road’ Shiel for the Great Glen, passing St Giles Cathedral, John Knox House Day 4 Day 6 recalling the road-building programme through Fort William for overnight in are just a few of the historic sites on that was started here in order to provide Ballachulish or Glencoe area. -

The Earldom of Ross, 1215-1517

Cochran-Yu, David Kyle (2016) A keystone of contention: the Earldom of Ross, 1215-1517. PhD thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/7242/ Copyright and moral rights for this thesis are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Glasgow Theses Service http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] A Keystone of Contention: the Earldom of Ross, 1215-1517 David Kyle Cochran-Yu B.S M.Litt Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Ph.D. School of Humanities College of Arts University of Glasgow September 2015 © David Kyle Cochran-Yu September 2015 2 Abstract The earldom of Ross was a dominant force in medieval Scotland. This was primarily due to its strategic importance as the northern gateway into the Hebrides to the west, and Caithness and Sutherland to the north. The power derived from the earldom’s strategic situation was enhanced by the status of its earls. From 1215 to 1372 the earldom was ruled by an uninterrupted MacTaggart comital dynasty which was able to capitalise on this longevity to establish itself as an indispensable authority in Scotland north of the Forth. -

Strathnaver Province Archaeology Project: Langdale, Grumbeg, Achadh an Eas & & the Tulloch Data Structure Report 2007

STRATHNAVER PROVINCE ARCHAEOLOGY PROJECT: LANGDALE, GRUMBEG, ACHADH AN EAS & & THE TULLOCH DATA STRUCTURE REPORT 2007 PROJECT 2406 carried out on behalf of Historic Scotland Contents 1.0 Executive Summary 7 2.0 Introduction 7 3.0 Site Location and Topography 7 4.0 Archaeological Background 7 5.0 Aims and Objectives 9 6.0 Methodology 10 7.0 Results 11 7.1 Langdale 12 7.2 Achadh an Eas 13 7.3 Grumbeg 16 7.4 The Tulloch 18 8.0 Discussion 19 9.0 Recommendations 19 10.0 Acknowledgements 19 11.0 Bibliography 20 12.0 Gazetteer of Sites 21 12.1 Langdale 21 12.2 Achadh an Eas 24 12.3 Grumbeg 26 12.4 DES 28 List of Figures Figure 1: Site Location 6 Figure 2: Extract from the first edition OS map (1878) of Langdale 11 Figure 3: Extract from the first edition OS map (1878) of Achadh an Eas 15 Figure 4: Extract from the first edition OS map (1878) of Grumbeg 16 Figure 5: Survey Plan of The Tulloch with Contour Model 17 List of Plates Plate 1: Cluster B at Langdale, from the north-west; The Tulloch lies beyond the trees 13 by the farmstead in background to left Plate 2: Longhouse in cluster G at Achadh an Eas, from the south-east 15 Plate 3: Longhouse GB 1 at Grumbeg Project website: http://www.northsutherlandarchaeology.org.uk © Glasgow University 2007 This report is one of a series published by GUARD, Gregory Building, Lilybank Gardens, Glasgow, G12 8QQ STRATHNAVER PROVINCE ARCHAEOLOGY PROJECT: LANGDALE, GRUMBEG, ACHADH AN EAS & THE TULLOCH DATA STRUCTURE REPORT 2007 PROJECT 2406 by Olivia Lelong and Amy Gazin-Schwartz This document has been prepared in accordance with GUARD standard operating procedures. -

Weekly List of Valid Planning Applications 4Th May 2018.Pdf

Weekly Planning list for 04 May2018 Page 1 Argyll and Bute Council Planning Weekly List of Valid Planning Applications Week ending 04 May2018 4/5/2018 10:4 Weekly Planning list for 04 May2018 Page 2 Bute and Cowal Reference: 18/00877/PP Offcer: StevenGove Telephone: 01546 605518 Ward Details: 08 - Isle Of Bute Community Council: Bute Community Council Proposal: Upgrade existing sash and case windows from single glazed units to double glazed units,replace lowerground foor window of the same style and fnish, replace entrance doors,remove wash house door and infll to match existing wall fnish, replace front steps handrail. Widening of entrance,and removal/reme- dial wor ks to boundarywalls.Erection of garden shed and installation of satellite dish. Location: 40 High Road, Por t Bannatyne,Isle Of Bute,Argyll And Bute, PA20 0PP Applicant: Mr and Mrs GarryChar nock Inverbroom, 40 High Road, Por t Bannatyne,PA20 0PP Ag ent: Farquhar Geddes Architects Br isbane Lodge,Brisbane Glen Road, Largs,KA30 8SL Development Type: N01 - Householder developments Grid Ref: 207987 - 667162 Reference: 18/00897/PP Offcer: StevenGove Telephone: 01546 605518 Ward Details: 08 - Isle Of Bute Community Council: Bute Community Council Proposal: Erection of 4 dwellinghouses Location: Plots 21 - 24 Eastlands Par k, Rothesay, Isle Of Bute,Argyll And Bute Applicant: George Hanson (Building Contractors) Ltd 20 Union Street, Rothesay, Isle of Bute,PA20 0HD Ag ent: G. D.Lodge Architects LLP Crown House,152 West Regent Street, Glasgow, G22RQ Development Type: N03B - Housing -

The Peatlands of Caithness & Sutherland

The Peatlands of Caithness & Sutherland MANAGEMENT STRATEGY The Peatlands of Caithness & Sutherland MANAGEMENT STRATEGY Contents # Foreword $ INTRODUCTION WHAT’S SO SPECIAL ABOUT THE PEATLANDS? $ # SO MANY TITLES % $ MANAGEMENT OF THE OPEN PEATLANDS AND ASSOCIATED LAND $ MANAGEMENT OF WOODLANDS IN AND AROUND THE PEATLANDS #$ % COMMUNITY AND ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT #( ' SPREADING THE MESSAGE ABOUT THE PEATLANDS $ ( WHAT HAPPENS NEXT? $# Bibliography $$ Annex Caithness and Sutherland peatlands SAC and SPA descriptions $% Annex Conservation objectives for Caithness and Sutherland Peatlands SAC and SPA $' Acknowledgements $( Membership of LIFE Peatlands Project Steering Group $( Contact details for LIFE Peatlands Project funding partners $( Acronyms and abbreviations Bog asphodel Foreword As a boy I had the great privilege of spending my summers at Dalnawillan= our family home= deep in what is now called the “Flow Country” Growing up there it was impossible not to absorb its beauty= observe the wildlife= and develop a deep love for this fascinating and unique landscape Today we know far more about the peatlands and their importance and we continue to learn all the time As a land manager I work with others to try to preserve for future generations that which I have been able to enjoy The importance of the peatlands is now widely recognised and there are many stakeholders and agencies involved The development of this strategy is therefore both timely and welcome The peatlands of Caithness and Sutherland are a special place= a vast and -

Sutherland and Caithness in Ancient Geography. 79 Sutherland and Caithness in Ancient Geography and Maps. by Rev. Angus Mackay

SUTHERLAND AND CAITHNESS IN ANCIENT GEOGRAPHY. 79 III. SUTHERLAND AND CAITHNESS IN ANCIENT GEOGRAPHY AND MAPS. BY REV. ANGUS MACKAY, M.A., CORK,. MEM. S.A. SCOT., WKSTERDAIE, CAITHNESS. Ptolem f Alexandriao y o flourishe 0 wh A.D.,14 . ,c dcompile a d geograph e theth nf o yknow n worl n eighi d t books, whic s suci h n ha improvement upon earlier attempt a simila f o s r kind tha t continuei t d n usi e until afte e revivath r f learnin o e l 15tth h n i g centurys Hi . longitudes were calculated fro e Canariesmpoina th n i t , supposee b o dt the westernmost part of the world; but he reckoned it as only 2J° west of Cape St Vincent, whereas the real distance is over 9°. Partly owing to this miscalculation, some countries are thrown considerably out of place when his data are reduced to map form; and this is especially true of Scotland, which fro e Clydm th Fortd ean h northwar s twistei d e du d east, making thence a right angle with England. Notwithstanding this glaring defect, however, his geography of the north of Scotland cannot fail to interest the antiquary in search of light upon the place-names and people of that part. Starting from the VOLSAS SINUS in the W., which he sets down in 30'whic° d latd an 60 ,.an long ° h 29 scholar. generallw sno y understand to indicate Lochalsh Kyle, the names of the places given by him, workin e easge th nort th roun ts follows o a t side hy e b dar , , with Ptolemaic long latd .an , respectively rivee Th r 30'° .Nabarus 60 ; x ° 30 , e promontorth y Tarvedu r Capmo e Orkas 20'° ° 15'e 31 pro,x 60 th ; - montory Virvedrum, 31° x 60°; the promontory Verubium, 30° 30' x 59° 40'; the river Ila, 30° x 59° 40'; and Alta Eipa, 29° x 59° 40', the bank e Oykelloth f , between. -

JOHNSTON's CLAN HISTORIES ORA L\!Rf '"'.'I' 1R It'/ R'al!FORNIA G; , --\L Uti;~ ~~ SOCI ETY NC=~

• JOHNSTON'S CLAN HISTORIES ORA l\!rF '"'.'I'_ 1r iT'/ r'AL!FORNIA G;_ , _ --\L Uti;~ ~~ SOCI ETY NC=~ SCU\d.,,. t 0 °""'! PERSONAL ARMS OF LORD REAY, CHIEF OF CLAN MACKAY JOHNSTON'S CLAN HISTORIES THE CLAN MACKAY Clansman's Badgt JOHNSTON'S CLAN HISTORIES THE CLAN CAMERON. BY C.I. FRASER OF REELIG, Sometime Albany Herald. THE CLAN CAMPBELL. BY ANDREW MCKERRAL, C.I.E. THE CLAN DONALD. (Macdonald, Macdonell, Macalister). BY I.F GRANT, LL.D. THE FERGUSSONS. BY SIR JAMES FERGUSSON OF KILKERRAN, BT. THE CLAN FRASER OF LOVAT. BY C.I. FRASER OF REELIG, Sometime Albany Herald. TIIE CLAN GORDON. BY JEAN DUN LOP, PH.D. THE GRAHAMS. BY JOHN STEWART OF ARDVORLICH. THE CLAN GRANT. BY I.F. GRANT, LL.D. THE KENNEDYS. BY SIR JAMES FERGUSSON OF KILKERRAN, BT. THE CLAN MACGREGOR. BY W.R. KERMACK. THE CLAN MACKAY. BY MARGARET 0. MACDOUGALL. THE CLAN MACKENZIE. BY JEAN DUNLOP, PH.D. THE CLAN MACKINTOSH. BY JEAN DUNLOP, PH.D. THE CLAN MACLEAN . BY JOHN MACKECHNIE. THE CLAN MACLEOD. BY 1.F. GRANT, LL.D. THE CLAN MACRAE. BY DONALD MACRAE. THE CLAN MORRISON. BY ALICK MORRISON. THE CLAN MUNRO. BY C.I. FRASER OF REELIG,Sometime Albany Herald. THE ROBERTSONS. BY SIR IAIN MONCREIFFE OF THAT ILK, BT. Albany Herald. THE CLAN ROSS. BY DONALD MACKINNON, D. LITT. THE SCOITS. BY JEAN DUNLOP, PH.D. THE STEWARTS . BY JOHN STEWART OF ARDVORLICH. THE CLAN MACKAY A CELTIC RESISTANCE TO FEUDAL SUPERIORITY BY MARGARET 0. MACDOUGALL, F.S.A. Scot. Late Librarian, l nvtrntss Public Library With Tartan and Chief's Arms in Colour, and a Map JOHNSTO N & BACON PUBLISHERS EDINBURGH AND LONDON FIRST PUBLISHED 1953 SECOND EDITION 1963 REPRINTED 1969 REPRINTED 1972 SBN 7179 4529 4 @ Johnston & Bacon Publishers PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN BY LOWE AND BRYDONE ( PRINTERS) LIMITED, LONDON I Duthaich Mlzic Aoidh, familiarly known as the Mackay country, covered approximately five-eighths of the County of Sutherland. -

The Highland Clans of Scotland

:00 CD CO THE HIGHLAND CLANS OF SCOTLAND ARMORIAL BEARINGS OF THE CHIEFS The Highland CLANS of Scotland: Their History and "Traditions. By George yre-Todd With an Introduction by A. M. MACKINTOSH WITH ONE HUNDRED AND TWENTY-TWO ILLUSTRATIONS, INCLUDING REPRODUCTIONS Of WIAN'S CELEBRATED PAINTINGS OF THE COSTUMES OF THE CLANS VOLUME TWO A D. APPLETON AND COMPANY NEW YORK MCMXXIII Oft o PKINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN CONTENTS PAGE THE MACDONALDS OF KEPPOCH 26l THE MACDONALDS OF GLENGARRY 268 CLAN MACDOUGAL 278 CLAN MACDUFP . 284 CLAN MACGILLIVRAY . 290 CLAN MACINNES . 297 CLAN MACINTYRB . 299 CLAN MACIVER . 302 CLAN MACKAY . t 306 CLAN MACKENZIE . 314 CLAN MACKINNON 328 CLAN MACKINTOSH 334 CLAN MACLACHLAN 347 CLAN MACLAURIN 353 CLAN MACLEAN . 359 CLAN MACLENNAN 365 CLAN MACLEOD . 368 CLAN MACMILLAN 378 CLAN MACNAB . * 382 CLAN MACNAUGHTON . 389 CLAN MACNICOL 394 CLAN MACNIEL . 398 CLAN MACPHEE OR DUFFIE 403 CLAN MACPHERSON 406 CLAN MACQUARIE 415 CLAN MACRAE 420 vi CONTENTS PAGE CLAN MATHESON ....... 427 CLAN MENZIES ........ 432 CLAN MUNRO . 438 CLAN MURRAY ........ 445 CLAN OGILVY ........ 454 CLAN ROSE . 460 CLAN ROSS ........ 467 CLAN SHAW . -473 CLAN SINCLAIR ........ 479 CLAN SKENE ........ 488 CLAN STEWART ........ 492 CLAN SUTHERLAND ....... 499 CLAN URQUHART . .508 INDEX ......... 513 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Armorial Bearings .... Frontispiece MacDonald of Keppoch . Facing page viii Cairn on Culloden Moor 264 MacDonell of Glengarry 268 The Well of the Heads 272 Invergarry Castle .... 274 MacDougall ..... 278 Duustaffnage Castle . 280 The Mouth of Loch Etive . 282 MacDuff ..... 284 MacGillivray ..... 290 Well of the Dead, Culloden Moor . 294 Maclnnes ..... 296 Maclntyre . 298 Old Clansmen's Houses 300 Maclver .... -

CGSNA New Member Booklet

HE EPTS OF LAN UNN T S C G Alexander George Gunn, James Magnus Robert Thomas Allisterson the Crowner Jameson MacMain George MacComas MacAllister Corner Jamieson MacManus Georgeson MacOmish Sandeson Croner Jamison Magnus MacGeorge Thomson Sandison Crownar MacHamish Magnusson MacRobb Tomson Crowner MacSheoras Main MacRory Cruiner Mains Robb Torquil Andres Cruner Maness Robeson MacCorkhill Andresson MacChruner Mann Robinson MacCorkill John Manson Robison MacCorkle Johnson Manus Robson MacCullie Gunn Kean Rorieson David Ganson Keene William MacDade Gaunson MacIan Neil MacWilliam MacDhaidh MacKames MacNeil Sweyn More MacKeamis Neillson Swain Wiley Henry MacKeamish Neilson Swan Will “Foreigner” Eanrig MacKean Nelson Swann Williamson Gailey Enrick MacKeanis Swanney Wills Galdie Enrig MacKendrick Swannie Willson Galley Henderson Swanson Wilson Gallie Inrig Wylie Gauldie MacEnrick Wyllie ISIT US ON THE WEB AT WWW CLANGUNN US V . to house those cleared from the interior of the County of Sutherland at the beginning of the 19th century. Kildonan - named after St. Donan who established his monastery at Suisgill; in the middle of the glen was the home of the McHamish Gunns from the 15th century up to the Clearances in 1819. The original church of Kildonan probably dated from about 1100 and contained the mortuary chapel of the Gunn chiefs at its western end. This was replaced by the present church built in 1788. Down the river from the church is Killearnan the seat of the McHamish Gunns for over 200 years until it was destroyed bv fire in 1690. Nothing remains of the original house. Kinbrace - at the top of Kildonan is said to have been named after the Crowner’s brooch. -

Souterrains in Sutherland

SOUTERRAINS IN SUTHERLAND Alex. Morrison BACKGROUND The terminology of these sites has varied considerably over the past 150 years, with labels such as Pier's house, eirde house, earth-house (RCAHMS Sutherland Inventory 1911 ), we em and leabidh jholaich being used at different times, and mostly suggesting a dwelling or refuge function. Some of this has been discussed by Broth well (1977. 179), who avoided the word souterrain as: ... a more cautious term - covering as it does an underground passage, tunnel, subway structure - but does not imply any expanded or terminal 'living' or 'storage' area which some seem to show, and it is difficult to determine how much of some structures was originally underground. Most recent writers on the subject appear to be well aware of the limitations involved in the use of the word 'sou terrain', and of the implications for living, storage and even possible 'ritual' functions of the surviving remains. Despite the lack of evidence, in some cases, as to whether the structures were completely or partially underground, the word 'souterrain' will be retained here, and will be used to refer to structures of 'typical' souterrain shape- to passages, more or less curved; and to underground chambers which might not be passages but which seem, in some examples, to have good evidence of being attached to surface structures. The number of structures under this heading [Fig. I 0.1] is not large for the size of the area involved, nor is the information available consistent in quantity and quality. Not all structures recorded in the 1911 Royal Commission Inventory and later sources are undoubted souterrains, and some of the sites listed here have a question mark against them as an indicator of incomplete information. -

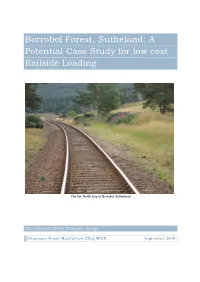

Borrobol Forest, Sutheland: a Potential Case Study for Low Cost Railside Loading

Borrobol Forest, Sutheland: A Potential Case Study for low cost Railside Loading The Far North Line at Borrobol, Sutherland The Highland Timber Transport Group Chairman: Frank MacCulloch CEng MICE September 2008 CONTENTS CONTENTS ............................................................................................................................................................................ 1 THE ROLE OF THE HIGHLAND TIMBER TRANSPORT GROUP .............................................................................................. 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................................................................................ 1 KEY PLAN................................................................................................................................................................................... 2 INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................................................................... 2 BACKGROUND .......................................................................................................................................................................... 3 EXTRACTION FROM BORROBOL ............................................................................................................................................ 4 CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATION .............................................................................................................................