Livability Study What We Learned Report Sparwood Livability Study - What We Learned Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Contract Specialist Teck Resources Ltd – Sparwood Shared Services, Sparwood, BC Posting Date: July 23, 2021

Teck Coal Limited Recruiting Centre RR #1, Highway #3 +1 250 425 8800 Tel Sparwood, B.C. Canada V0B 2G0 www.teck.com Job Opportunity Contract Specialist Teck Resources Ltd – Sparwood Shared Services, Sparwood, BC Posting Date: July 23, 2021 Closing Date: August 22, 2021 Reporting to the Purchasing Supervisor, the Contract Specialist, (known at Teck as the Purchasing Agent) is responsible for acquiring the best total value in the acquisition of materials and services to meet ongoing needs and support initiatives. To be successful, we are looking for someone capable of working under minimal direction and who functions best in a high-performance atmosphere; someone who has strong interpersonal and communication skills, who can mentor others. Excellent negotiating, problem-solving, and decision-making skills are vital. You will have the opportunity to implement procedural improvements to streamline business practices and be instrumental in the successful execution of contracts. You will also have the ability to interact with both operations and support and contract groups throughout our company, gaining knowledge of our mining business. Join us in the breathtaking Elk Valley of British Columbia. Here you will find outdoor adventure at your fingertips. Whether it's biking and skiing, or the laid- back atmosphere of fishing and hiking, there is something for everyone! With an attractive salary, benefits, and Earned Day Off schedule, come experience what work life balance is all about! Responsibilities: • Be a courageous safety leader, adhere -

Highway 3: Transportation Mitigation for Wildlife and Connectivity in the Crown of the Continent Ecosystem

Highway 3: Transportation Mitigation for Wildlife and Connectivity May 2010 Prepared with the: support of: Galvin Family Fund Kayak Foundation HIGHWAY 3: TRANSPORTATION MITIGATION FOR WILDLIFE AND CONNECTIVITY IN THE CROWN OF THE CONTINENT ECOSYSTEM Final Report May 2010 Prepared by: Anthony Clevenger, PhD Western Transportation Institute, Montana State University Clayton Apps, PhD, Aspen Wildlife Research Tracy Lee, MSc, Miistakis Institute, University of Calgary Mike Quinn, PhD, Miistakis Institute, University of Calgary Dale Paton, Graduate Student, University of Calgary Dave Poulton, LLB, LLM, Yellowstone to Yukon Conservation Initiative Robert Ament, M Sc, Western Transportation Institute, Montana State University TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Tables .....................................................................................................................................................iv List of Figures.....................................................................................................................................................v Executive Summary .........................................................................................................................................vi Introduction........................................................................................................................................................1 Background........................................................................................................................................................3 -

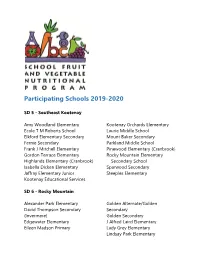

Participating Schools 2019-2020

Participating Schools 2019-2020 SD 5 - Southeast Kootenay Amy Woodland Elementary Kootenay Orchards Elementary Ecole T M Roberts School Laurie Middle School Elkford Elementary Secondary Mount Baker Secondary Fernie Secondary Parkland Middle School Frank J Mitchell Elementary Pinewood Elementary (Cranbrook) Gordon Terrace Elementary Rocky Mountain Elementary Highlands Elementary (Cranbrook) Secondary School Isabella Dicken Elementary Sparwood Secondary Jaffray Elementary Junior Steeples Elementary Kootenay Educational Services SD 6 - Rocky Mountain Alexander Park Elementary Golden Alternate/Golden David Thompson Secondary Secondary (Invermere) Golden Secondary Edgewater Elementary J Alfred Laird Elementary Eileen Madson Primary Lady Grey Elementary Lindsay Park Elementary Martin Morigeau Elementary Open Doors Alternate Education Marysville Elementary Selkirk Secondary McKim Middle School Windermere Elementary Nicholson Elementary SD 8 - Kootenay Lake Adam Robertson Elementary Mount Sentinel Secondary Blewett Elementary School Prince Charles Brent Kennedy Elementary Secondary/Wildflower Program Canyon-Lister Elementary Redfish Elementary School Crawford Bay Elem-Secondary Rosemont Elementary Creston Homelinks/Strong Start Salmo Elementary Erickson Elementary Salmo Secondary Hume Elementary School South Nelson Elementary J V Humphries Trafalgar Middle School Elementary/Secondary W E Graham Community School Jewett Elementary Wildflower School L V Rogers Secondary Winlaw Elementary School SD 10 - Arrow Lakes Burton Elementary School Edgewood -

CP's North American Rail

2020_CP_NetworkMap_Large_Front_1.6_Final_LowRes.pdf 1 6/5/2020 8:24:47 AM 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Lake CP Railway Mileage Between Cities Rail Industry Index Legend Athabasca AGR Alabama & Gulf Coast Railway ETR Essex Terminal Railway MNRR Minnesota Commercial Railway TCWR Twin Cities & Western Railroad CP Average scale y y y a AMTK Amtrak EXO EXO MRL Montana Rail Link Inc TPLC Toronto Port Lands Company t t y i i er e C on C r v APD Albany Port Railroad FEC Florida East Coast Railway NBR Northern & Bergen Railroad TPW Toledo, Peoria & Western Railway t oon y o ork éal t y t r 0 100 200 300 km r er Y a n t APM Montreal Port Authority FLR Fife Lake Railway NBSR New Brunswick Southern Railway TRR Torch River Rail CP trackage, haulage and commercial rights oit ago r k tland c ding on xico w r r r uébec innipeg Fort Nelson é APNC Appanoose County Community Railroad FMR Forty Mile Railroad NCR Nipissing Central Railway UP Union Pacic e ansas hi alga ancou egina as o dmon hunder B o o Q Det E F K M Minneapolis Mon Mont N Alba Buffalo C C P R Saint John S T T V W APR Alberta Prairie Railway Excursions GEXR Goderich-Exeter Railway NECR New England Central Railroad VAEX Vale Railway CP principal shortline connections Albany 689 2622 1092 792 2636 2702 1574 3518 1517 2965 234 147 3528 412 2150 691 2272 1373 552 3253 1792 BCR The British Columbia Railway Company GFR Grand Forks Railway NJT New Jersey Transit Rail Operations VIA Via Rail A BCRY Barrie-Collingwood Railway GJR Guelph Junction Railway NLR Northern Light Rail VTR -

Inter-Community Business Licence Listing

Inter-Community Business Licence Listing 11 AGRICULTURE, FORESTRY, FISHING AND HUNTING This sector comprises establishments primarily engaged in providing related support activities to businesses primarily engaged in growing crops, raising animals, harvesting timber, harvesting fish and other animals from their natural habitats. ANIMAL PRODUCTION AND AQUACULTURE (112) This subsector comprises establishments, such as ranches, farms and feedlots, primarily engaged in raising animals, producing animal products and fattening animals. Industries have been created taking into account input factors such as suitable grazing or pasture land, specialized buildings, type of equipment, and the amount and type of labour required. Business Name Contact Contact Phone Contact Email Business Mailing Address Issued By Name FORESTRY AND LOGGING (113) This subsector comprises establishments primarily engaged in growing and harvesting timber on a long production cycle (of ten years or more) Business Name Contact Contact Phone Contact Email Business Mailing Address Issued By Name Lean Too David PO Box 16D Fernie, BC 250.423.9073 Endeavours Ltd Henderson V0B 1M5 FISHING, HUNTING AND TRAPPING (114) This subsector comprises establishments primarily engaged in catching fish and other wild animals from their natural habitats. Business Name Contact Contact Phone Contact Email Business Mailing Address Issued By Name SUPPORT ACTIVITIES FOR AGRICULTURE AND FORESTRY (115) This subsector comprises establishments primarily engaged in providing support services that are essential to agricultural and forestry production. Business Name Contact Contact Phone Contact Email Business Mailing Address Issued By Name West Fork Tracy 305E Michel Creek Road, District of Resource 250.433.1256 Kaisner Sparwood, BC Sparwood Management 21 MINING, QUARRYING, AND OIL AND GAS EXTRACTION This sector comprises establishments primarily engaged providing support activities to businesses engaged in extracting naturally occurring minerals. -

Amenity Migration and the Growing Pains of Western Canadian Mountain Towns

The Search for Paradise: Amenity migration and the growing pains of western Canadian mountain towns Presented at the Canadian Political Science Association Vancouver, British Columbia, June 2008 Lorna Stefanick Associate Professor, Athabasca University [email protected] Migration is not a new phenomenon, it has been happening since the dawn of human history. What is new is that toward the end of the 2nd millennium the motivation for this migration changed. In the past people moved primarily in search of food, or later, for economic reasons. Now there is a significant movement of people occurring because of a desire to attain a particular lifestyle: migrants are seeking a particular environment and a differentiated culture associated with rural areas, and in particular, rural areas located in coastal or mountain regions. This movement of humans to smaller communities in rural areas is referred to as “amenity migration,” a phenomenon that stands in sharp contrast the rapid urbanization and suburbanization that occurred in the 20th century. The amenity migration phenomenon is happening worldwide, and as a result of globalization and internationalization the migration is also happening across national boundaries. Amenity migration is having a profound impact on previously remote communities, many of which were in economic decline. In North America, research on amenity migration has focused primarily on the western USA, especially the movement of urbanites to rural communities in the Rocky Mountains. Comparatively little work has been done in Canada. While the effects of amenity migration might be less pronounced in this country, it is beginning to create huge challenges for communities in the mountains of western Canada. -

The District of Sparwood Community Profile

THE DISTRICT OF SPARWOOD COMMUNITY PROFILE 1 Community Profile 3 District of Sparwood Overview 3 A Brief History 3 Location 3 Geography 4 First Nations 4 Wildlife 4 Climate 5 Demographics 6 Local Government 9 Primary Economic Structures 10 Emerging Industries 12 Community Services and Amenities 14 Education 14 Health Services 15 Government Services 16 Financial Services 17 Transportation 18 Utilities and Technological Services 19 Sparwood Community Network (SCN) 20 Media 21 Real Estate 22 Recreation and Tourism 23 Cultural and Social Amenities 25 Economic Development Profile 26 Business Advantages 26 Reasons to Invest 27 Investment / Business Opportunities 29 Natural Resource Potential 29 Tourism Related Businesses 29 Services 30 Construction / Development 30 Retail 31 Access to Markets 31 Federal and Provincial Taxes 32 Business Resources 34 Databases and e-Links 35 2 District of Sparwood Overview A Brief History1 Prior to 1900, there was a railroad stop known as Sparwood, which was so named because of the trees from this area being shipped to the Coast for manufacturing spars for ocean vessels. In the late 1800s and early 1900s, coal development in this area resulted in the creation of three small communities known as Michel, Natal and Sparwood, respectively. The former two communities were in the immediate area of the coal mines and the latter, Sparwood, was a few miles removed.. By 1966, the Village of Natal and the settlement of Michel had become adversely affected by coal dust. There was no regulatory legislation to protect the public. The Village of Natal, in cooperation with the Provincial and Federal Governments, entered into an Urban Renewal and Land Assembly program, which eventually resulted in the townspeople of Natal and Michel moving to, and expanding, Sparwood. -

Kootenay Powder Highway Ski

2 Grande 38 45 Cache 45 37 32 15 22 Ft Saskatewan 36 43 40 16 St Albert 16 Edson Sherwood Park Spruce Vegreville Vermilion Grove 16 22 Edmonton 14 Hinton Devon Leduc Tofield Drayton 14 39 21 Valley 2 20 Camrose 26 13 13 Wetaskiwin 16 Jasper 13 Wainwright 2A 56 Jasper 53 Ponoka 53 93 National 22 Park 21 Lacombe 12 36 Sylvan 11 Nordegg Stettler Lake Rocky 11 Red Deer 12 Columbia Icefield Mountain House 11 Cline River 22 42 54 54 21 Avola Jasper Red Deer 145 km 90 mi Revelstoke to 229 km 142 mi Rocky Mountain House Edmonton 294 km 182 mi Mica in the Rockies Driving84 km 52 Times mi Quick Reference 140 km 87 mi 584 27 27 Appsolutely Golden to Revelstoke ......................... Sundre2 hr Calgary to Golden ............................Olds 3 hr Resorts Fairmont Hot Springs Resort ... FairmontHotSprings.com Clearwater *Revelstoke to Rossland ................ 4 hr, 15 min Calgary to Fernie ...................... 3 hr, 30 min Three Hills Hanna KOOTENAY *Revelstoke to Nelson .................. 3 hr, 45 min Lethbridge to Fernie ................... .2 hr, 30 min Fernie Alpine Resort .................. SkiFernie56.com 5 all you need! Nelson to Rossland .................... .1 hr, 15 min Kamloops to Revelstoke ................ .2 hr, 40 min Kicking Horse Mtn Resort ..... KickingHorseResort45 km 28 mi .com9 Didsbury 27 24 Nelson to Cranbrook .......................... 3 hr Kelowna to Revelstoke ................. .2 hr, 50 min Kimberley Alpine Resort ............ SkiKimberley.com i m C Rossland to Cranbrook ................. .3 hr, 10 min Kelowna to Rossland .......................... 4 hr Panorama Mountain Village ......... SkiPanorama .com K 3 1 i n b A m 24 k a m Cranbrook to Fernie ................... -

From the Municipality of Crowsnest Pass to the Joint Review Panel Re

January 10, 2019 Canadian Environmental Assessment Agency Review Panel Manager Grassy Mountain Coal Project 160 Elgin Street, 22nd Floor, Ottawa ON K1A 0H3 [email protected] Dear Sir or Madam: Re: Letter of Support – Benga Mining Limited/Riversdale Resources - Grassy Mountain Coal Project Reference No. 80101 The history of the Municipality of Crowsnest Pass is steeped in the coal mining industry. The five communities that form our beautiful municipality are the result of an operating coal mine in each town. When coal mining was at its height, the town of Frank was known as the Pittsburgh of Canada. The hotels were full, real estate was booming, taxes were low and all the communities blossomed with recreational opportunities, lively main streets and prosperous businesses. Since the closing of the last coal mine in the area in 1983, the five towns saw a steady decline in their economy. We are now a community where 93% of our tax base is residential and only 7% industrial. We are a poor community trying to make ends meet on the backs of our residents. It’s difficult to look west and see the thriving communities of Sparwood, Elkford and Fernie, all flourishing because of the active coal mines surrounding their communities. In order to prosper, this community is in desperate need of industry… Why not the industry that is literally in our back yards? We were born from coal in the ground and we can again prosper through this resource. Most of the residents who earn a decent income in Crowsnest Pass do so by driving to work at the Teck Resources mines across the border. -

Community Profile 2 2 Table of Contents

COMMUNITY PROFILE 2 www.sparwood.ca 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS About Sparwood .................................4 Economy and Employment ..................17 Community Services ...........................25 Tourism and Recreation .......................32 The Business Case ..............................38 ABOUT SPARWOOD www.sparwood.ca 4 A WARM WELCOME It’s not often you come across a place with the right mix. Where economic opportunity, family, and recreation blend together as well as they do here. Sparwood is a Rocky Mountain community that is abundant with ambition and drive, welcoming of hard work and determination. It is a community with many facets, home to people from many backgrounds. Located in the beautiful Elk Valley, within the East Kootenays, and conveniently central to Teck Coal’s five metallurgical coal mines, Sparwood offers convenient access to work and play for people with a keen interest in the outdoor lifestyle. www.sparwood.ca 5 www.sparwood.ca 6 OUR AMBITION Sparwood’s Official Community Plan (OCP) looks forward to 2035 and for good reason, planning is critical to success and Sparwood is focused on creating a diverse economy that will provide a range of jobs and services to supplement the mining industry, which will continue to be our economic lifeblood. In 2035 Sparwood will continue to promote compact development and mixed use as the means to achieve a walkable community that provides efficient and sustainable infrastructure, minimizing negative impacts on the environment. www.sparwood.ca 7 www.sparwood.ca 8 ROOTS Sparwood is located in the traditional Ktunaxa (pronounced ‘k-too-nah-ha’) people have territory of the Ktunaxa Nation, which occupied the lands adjacent to the Kootenay and covers approximately 70,000 km² (27,000 mi²) within the Kootenay region of south- Columbia Rivers and the Arrow Lakes of British eastern British Columbia and historically Columbia, Canada for more than 10,000 years. -

ASSESSMENT of the PLANNING and DEVELOPMENT of TUMBLER RIDGE, BRITISH COLUMBIA by SUSAN Mcgrath BA(Hons)

LOCAL GOVERNANCE: ASSESSMENT OF THE PLANNING AND DEVELOPMENT OF TUMBLER RIDGE, BRITISH COLUMBIA By SUSAN McGRATH B.A.(Hons), The University of Western Australia, 1979 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES School of Community and Regional Planning We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA October 1985 © Susan McGrath, 1985 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of CoMwu imUj OUAJ KQ^IQIOJ MCUM^1 The University of British Columbia 1956 Main Mall Vancouver, Canada V6T 1Y3 Date QtLLu lAlrf... lUb' JE-6 C3/81) i ABSTRACT Tumbler Ridge, a resource town situated in northeastern British Columbia, is the first new community developed using the "local govern• ment" model. The context for the case study is provided by an examination of resource community development in British Columbia and Western Australia during the post-war period. In both jurisdictions a transition in resource community development methods is evident. The main stimulus for these changes has been the recognition of a variety of endogenous and exogenous problems associated with earlier methods of development. -

Small Town. Big Story. Community Overview

The District of Sparwood SmaLL Town. Big StorY. CommunitY OVerView ABOUT SPARWOOD with our coal. We’re a coal mining town, but that’s not all we have to do here. We’re situated in the heart of the Sparwood may be the first town in BC, if you’re arriving Rocky Mountains, surrounded by forests, wildlife, some from the east on Highway 3; or we may be ‘that town with of the purest water on earth, and an incredible array of the big truck.’ Or we might simply be known as that place things to do just out the back door. We’ve got world class on BC’s border in the beautiful Rocky Mountains. skiing only half an hour away, a great little golf course, If there’s one thing we are to everyone, it’s a mining incredible walking, biking and hiking trails, world class community; a collection of hard-working fun-loving people canoeing and kayaking on the Elk River, and exceptional who happily call Sparwood home. We’re proud to share hunting, fishing and off-road adventuring. And don’t forget that with you. Whether you’re passing through, headed our top notch recreational centre, a hit with the kids, west just down the road to Fernie — our neighbouring boasting a salt water pool, gym, fitness centre and more. tourism destination community, or if you’re headed further If you’re interested in good old small town fun stop by our to the land of sushi, traffic jams and killer whales. Perhaps visitor centre and see what adventures Sparwood has in you’re going east to the prairies and big skies, or maybe store for you! you’re just about to stay here and enjoy Rocky Mountain life..