The Invisible Hand

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oklahoma City Channel Lineup

Name Call Letters Number Name Call Letters Number Name Call Letters Number Fox College Sports - Central ** FCSC 648 Nicktoons NKTN 316 ActionMAX ACTMAX 835 Oklahoma City Fox College Sports - Pacific ** FCSP 649 Noggin NOG 320 Cinemax MAX 832 Fox Movie Channel FMC 792 Oxygen OXGN 368 Cinemax - West MAX-W 833 Fox News Channel FNC 210 PBS KIDS Sprout SPROUT 337 Encore ENC 932 Fox Reality Channel REAL 130 qubo qubo 328 Encore - West ENC-W 933 Channel Directory Fox Soccer Channel ** FSC 654 QVC QVC 197 Encore Action ENCACT 936 BY CHANNEL NAME Fox Sports en Español ** FSE 655 QVC QVC 420 Encore Drama ENCDRA 938 FSN Arizona ** FSAZ 762 Recorded TV Channel DVR 9999 Encore Love ENCLOV 934 FSN Detroit ** FSD 737 Sci Fi Channel SCIFI 151 Encore Mystery ENCMYS 935 Name Call Letters Number FSN Florida ** FSFL 720 Science Channel SCI 258 Encore Wam WAM 939 FSN Midwest ** FSMW 748 ShopNBC SHPNBC 424 Encore Westerns ENCWES 937 FSN North ** FSN 744 SiTV SiTV 194 FLIX FLIX 890 LOCAL LISTINGS FSN Northwest ** FSNW 764 Sleuth SLEUTH 161 HBO HBO 802 FSN Ohio-Cincinnati ** FSOHCI 732 Smile of a Child SMILE 340 HBO - West HBO-W 803 HSN HSN 8 FSN Ohio-Cleveland ** FSOHCL 734 SOAPnet SOAP 365 HBO Comedy HBOCOM 808 KAUT-43 (MY NETWORK TV) KAUT 43 FSN Pittsburgh ** FSP 730 SOAPnet - West SOAP-W 366 HBO Family HBOFAM 806 KETA-13 (PBS) KETA 13 FSN Prime Ticket ** FSPT 774 Speed Channel ** SPEED 652 HBO Latino HBOLAT 810 KFOR-4 (NBC) KFOR 4 FSN Rocky Mountain ** FSRM 760 Spike TV SPKE 145 HBO Signature HBOSIG 807 KOCB-34 (THE CW) KOCB 34 FSN South ** FSS 724 Spike -

Annual Report 2007 Creating and Distributing Top-Quality News, Sports and Entertainment Around the World

Annual Report 2007 Creating and distributing top-quality news, sports and entertainment around the world. News Corporation As of June 30, 2007 Filmed Entertainment WJBK Detroit, MI Latin America United States KRIV Houston, TX Cine Canal 33% Fox Filmed Entertainment KTXH Houston, TX Telecine 13% Twentieth Century Fox Film KMSP Minneapolis, MN Australia and New Zealand Corporation WFTC Minneapolis, MN Premium Movie Partnership 20% Fox 2000 Pictures WTVT Tampa Bay, FL Fox Searchlight Pictures KSAZ Phoenix, AZ Cable Network Programming Fox Atomic KUTP Phoenix, AZ United States Fox Music WJW Cleveland, OH FOX News Channel Twentieth Century Fox Home KDVR Denver, CO Fox Cable Networks Entertainment WRBW Orlando, FL FX Twentieth Century Fox Licensing WOFL Orlando, FL Fox Movie Channel and Merchandising KTVI St. Louis, MO Fox Regional Sports Networks Blue Sky Studios WDAF Kansas City, MO (15 owned and operated) (a) Twentieth Century Fox Television WITI Milwaukee, WI Fox Soccer Channel Fox Television Studios KSTU Salt Lake City, UT SPEED Twentieth Television WBRC Birmingham, AL FSN Regency Television 50% WHBQ Memphis, TN Fox Reality Asia WGHP Greensboro, NC Fox College Sports Balaji Telefilms 26% KTBC Austin, TX Fox International Channels Latin America WUTB Baltimore, MD Big Ten Network 49% Canal Fox WOGX Gainesville, FL Fox Sports Net Bay Area 40% Asia Fox Pan American Sports 38% Television STAR National Geographic Channel – United States STAR PLUS International 75% FOX Broadcasting Company STAR ONE National Geographic Channel – MyNetworkTV STAR -

The Work of the Critic

CHAPTER 1 The Work of the Critic Oh, gentle lady, do not put me to’t. For I am nothing if not critical. —Iago to Desdemona (Shakespeare, Othello, Act 2, Scene I) INTRODUCTION What is the advantage of knowing how to perform television criticism if you are not going to be a professional television critic? The advantage to you as a television viewer is that you will not only be able to make informed judgment about the television programs you watch, but also you will better understand your reaction and the reactions of others who share the experience of watching. Critical acuity enables you to move from casual enjoyment of a television program to a fuller and richer understanding. A viewer who does not possess critical viewing skills may enjoy watching a television program and experience various responses to it, such as laughter, relief, fright, shock, tension, or relaxation. These are fun- damental sensations that people may get from watching television, and, for the most part, viewers who are not critics remain at this level. Critical awareness, however, enables you to move to a higher level that illuminates production practices and enhances your under- standing of culture, human nature, and interpretation. Students studying television production with ambitions to write, direct, edit, produce, and/or become camera operators will find knowledge of television criticism necessary and useful as well. Television criticism is about the evaluation of content, its context, organiza- tion, story and characterization, style, genre, and audience desire. Knowledge of these concepts is the foundation of successful production. THE ENDS OF CRITICISM Just as critics of books evaluate works of fiction and nonfiction by holding them to estab- lished standards, television critics utilize methodology and theory to comprehend, analyze, interpret, and evaluate television programs. -

Channel Directory Channel Directory

Name Number Package Name Number Package Name Number Package EWTN 562 EWTN n l u i s National Geographic Channel 265 NGC n l u i s PREMIUM SUBSCRIPTIONS / A LA CARTE Hartford - New Haven FamilyNet 566 FAMNET n l u i s NFL Network ** 630 NFLNet u i s Fine Living 456 FINE u i s Nick2 315 NICK2 n l u i s @MAX 840 ATMAX s Fit TV 466 FIT TV n i s Nickelodeon 314 NICK n l u i s 5StarMAX 837 5STAR s Food Network 452 FOOD n l u i s Nickelodeon Games & Sports 322 GAS n u i s WMAX 838 WMAX s Channel Directory n l u i s Nicktoons 316 NKTN n u i s s Food Network - West 453 FOOD-W ActionMAX 835 ACTMAX BY CHANNEL NAME Fox College Sports - Atlantic ** 647 FCSA s v Noggin 320 NOG n l u i s Cinemax 832 MAX s Fox College Sports - Central ** 648 FCSC s v Oxygen 368 OXGN u i s Cinemax - West 833 MAX-W s Fox College Sports - Pacific ** 649 FCSP s v PBS KIDS Sprout 337 SPROUT n i s Encore 932 ENC i s Name Number Package Fox Movie Channel 792 FMC u i s QVC 197 QVC n l u i s Encore - West 933 ENC-W i s Fox News Channel 210 FNC l u i s QVC 420 QVC n l u i s Encore Action 936 ENCACT i s Fox Reality Channel 130 REAL u i s Recorded TV Channel 9999 DVR n l u i s Encore Drama 938 ENCDRA i s LOCAL LISTINGS Fox Soccer Channel ** 654 FSC i s Sci Fi Channel 151 SCIFI l u i s Encore Love 934 ENCLOV i s Fox Sports en Español ** 655 FSE s v Sci Fi Channel - West 152 SCFI-W l u i s Encore Mystery 935 ENCMYS i s HSN 7 HSN n l u i s FSN Arizona ** 762 FSAZ s v Science Channel 258 SCI n u i s Encore Wam 939 WAM i s WCTX-59 (MY NETWORK TV) 9 WCTX n l u i s FSN Detroit ** 737 FSD -

Along the Ohio Trail

Along The Ohio Trail A Short History of Ohio Lands Dear Ohioan, Meet Simon, your trail guide through Ohio’s history! As the 17th state in the Union, Ohio has a unique history that I hope you will find interesting and worth exploring. As you read Along the Ohio Trail, you will learn about Ohio’s geography, what the first Ohioan’s were like, how Ohio was discovered, and other fun facts that made Ohio the place you call home. Enjoy the adventure in learning more about our great state! Sincerely, Keith Faber Ohio Auditor of State Along the Ohio Trail Table of Contents page Ohio Geography . .1 Prehistoric Ohio . .8 Native Americans, Explorers, and Traders . .17 Ohio Land Claims 1770-1785 . .27 The Northwest Ordinance of 1787 . .37 Settling the Ohio Lands 1787-1800 . .42 Ohio Statehood 1800-1812 . .61 Ohio and the Nation 1800-1900 . .73 Ohio’s Lands Today . .81 The Origin of Ohio’s County Names . .82 Bibliography . .85 Glossary . .86 Additional Reading . .88 Did you know that Ohio is Hi! I’m Simon and almost the same distance I’ll be your trail across as it is up and down guide as we learn (about 200 miles)? Our about the land we call Ohio. state is shaped in an unusual way. Some people think it looks like a flag waving in the wind. Others say it looks like a heart. The shape is mostly caused by the Ohio River on the east and south and Lake Erie in the north. It is the 35th largest state in the U.S. -

21 Types of News

21 Types Of News In the fIrst several chapters, we saw media systems in flux. Fewer newspaper journalists but more websites, more hours of local TV news but fewer reporters, more “news/talk” radio but less local news radio, national cable news thriving, local cable news stalled. But what matters most is not the health of a particular sector but how these changes net out, and how the pieces fit together. Here we will consider the health of the news media based on the region of coverage, whether neigh- borhood, city, state, country, or world. Hyperlocal The term “hyperlocal” commonly refers to news coverage on a neighborhood or even block-by-block level. The tradi- tional media models, even in their fattest, happiest days could not field enough reporters to cover every neighborhood on a granular level. As in all areas, there are elements of progress and retreat. On one hand, metropolitan newspapers have cut back on regional editions, which in all likelihood means less coverage of neighborhoods in those regions. But the Internet has revolutionized the provision of hyperlocal information. The first wave of technology— LISTSERV® and other email groups—made it far easier for citizens to inform one another of what was happening with the neighborhood crime watch or the new grocery store or the death of citizens can now snap a beloved senior who lived on the block for 40 years. More recently, social media tools have enabled citizens to self-organize, and connect in ever more picture of potholes and dynamic ways. Citizens can now snap pictures of potholes and send them to send to city hall, or share city hall, or share with each other via Facebook, Twitter or email. -

Dawnco Low-Cost Upgrades Improve Reception DW – Discrete Wide 10

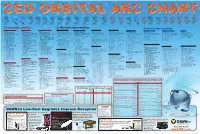

SES SES SES SES SES SES SES SES SES Intelsat SES SES SES SES Americom Americom Americom Americom Intelsat Intelsat Intelsat Intelsat Intelsat Americom Americom Americom Americom Intelsat Intelsat Americom Intelsat Galaxy 13/ Intelsat Americom Intelsat Americom Americom Americom AMC-6 Horizons-2 AMC-5 AMC-9 AMC-3 Galaxy 28 Galaxy 17 Galaxy 3C Galaxy 19 Galaxy 16 AMC-2 AMC-4 AMC-1 AMC-18 Galaxy 23 Galaxy 18 AMC-21 Galaxy 14 Horizons-1 Galaxy 27 AMC-11 Galaxy 15 AMC-10 AMC-7 AMC-8 72° WL 74.05° WL 78.95° WL 83° WL 87° WL 89° WL 91° WL 95.05° WL 97° WL 99° WL 100.95° WL 101° WL 103° WL 104.95° WL 121° WL 123° WL 124.9° WL 125° WL 127° WL 129° WL 131° WL 133° WL 135° WL 137° WL 139° WL C-band video satellites C-/Ku-band video satellites Ku-band video satellites SES Americom AMC-18 Intelsat Galaxy 23 SES Americom AMC-10 SES Americom AMC-6 SES Americom AMC-1 Intelsat Galaxy 28 Intelsat Galaxy 3C Intelsat Galaxy 16 SES Americom AMC-5 SES Americom AMC-21 Horizons-2 • 104.95° WL • 121° WL • 135° WL • 72° WL • 103* WL • 89° WL • 95.05° WL • 99° WL • 78.95° WL • 124.9° WL • 74.05° WL • Projected EOL: January 2022 • Projected EOL: August 2018 • Projected EOL: February 2019 • Projected EOL: December 2015 • Projected EOL: September 2011 • Projected EOL: June 2020 • Projected EOL: September 2020 • Projected EOL: August 2021 • Projected EOL: November 2010 • Projected EOL: October 2023 • Projected EOL: February 2023 • C-band – SSPA power: 20 watts • C-band – LTWTA power: 37 watts @ 36 MHz • C-band – SSPA power: 20 watts • C-band – SSPA power: 20 watts -

Super Bowl XLVIII on FOX Broadcast Guide

TABLE OF CONTENTS MEDIA INFORMATION 1 PHOTOGRAPHY 2 FOX SUPER BOWL SUNDAY BROADCAST SCHEDULE 3-6 SUPER BOWL WEEK ON FOX SPORTS 1 TELECAST SCHEDULE 7-10 PRODUCTION FACTS 11-13 CAMERA DIAGRAM 14 FOX SPORTS AT SUPER BOWL XLVIII FOXSports.com 15 FOX Sports GO 16 FOX Sports Social Media 17 FOX Sports Radio 18 FOX Deportes 19-21 SUPER BOWL AUDIENCE FACTS 22-23 10 TOP-RATED PROGRAMS ON FOX 24 SUPER BOWL RATINGS & BROADCASTER HISTORY 25-26 FOX SPORTS SUPPORTS 27 SUPERBOWL CONFERENCE CALL HIGHLIGHTS 28-29 BROADCASTER, EXECUTIVE & PRODUCTION BIOS 30-62 MEDIA INFORMATION The Super Bowl XLVIII on FOX broadcast guide has been prepared to assist you with your coverage of the first-ever Super Bowl played outdoors in a northern locale, coming Sunday, Feb. 2, live from MetLife Stadium in East Rutherford, NJ, and it is accurate as of Jan. 22, 2014. The FOX Sports Communications staff is available to assist you with the latest information, photographs and interview requests as needs arise between now and game day. SUPER BOWL XLVIII ON FOX CONFERENCE CALL SCHEDULE CALL-IN NUMBERS LISTED BELOW : Thursday, Jan. 23 (1:00 PM ET) – FOX SUPER BOWL SUNDAY co-host Terry Bradshaw, analyst Michael Strahan and FOX Sports President Eric Shanks are available to answer questions about the Super Bowl XLVIII pregame show and examine the matchups. Call-in number: 719-457-2083. Replay number: 719-457-0820 Passcode: 7331580 Thursday, Jan. 23 (2:30 PM ET) – SUPER BOWL XLVIII ON FOX broadcasters Joe Buck and Troy Aikman, Super Bowl XLVIII game producer Richie Zyontz and game director Rich Russo look ahead to Super Bowl XLVIII and the network’s coverage of its seventh Super Bowl. -

Channel Directory

Name Call Letters Number Name Call Letters Number Name Call Letters Number Fox News Channel FNC 210 qubo qubo 328 Encore Mystery ENCMYS 935 Sacramento/Stockton/Modesto Fox Reality Channel REAL 130 QVC QVC 197 Encore Wam WAM 939 Fox Soccer Channel ** FSC 654 QVC QVC 420 Encore Westerns ENCWES 937 Fox Sports en Español ** FSE 655 Recorded TV Channel DVR 9999 FLIX FLIX 890 FSN Arizona ** FSAZ 762 Sci Fi Channel - West SCFI-W 152 HBO HBO 802 Channel Directory FSN Bay Area FSBA 770 Science Channel SCI 258 HBO - West HBO-W 803 BY CHANNEL NAME FSN Detroit ** FSD 737 ShopNBC SHPNBC 424 HBO Comedy HBOCOM 808 FSN Florida ** FSFL 720 SiTV SiTV 194 HBO Family HBOFAM 806 FSN Midwest ** FSMW 748 Sleuth SLEUTH 161 HBO Latino HBOLAT 810 FSN North ** FSN 744 Smile of a Child SMILE 340 HBO Signature HBOSIG 807 Name Call Letters Number FSN Northwest ** FSNW 764 SOAPnet SOAP 365 HBO Zone HBOZNE 809 FSN Ohio-Cincinnati ** FSOHCI 732 SOAPnet - West SOAP-W 366 HBO2 HBO2 804 LOCAL LISTINGS FSN Ohio-Cleveland ** FSOHCL 734 Speed Channel ** SPEED 652 HBO2 - West HBO2-W 805 FSN Pittsburgh ** FSP 730 Spike TV SPKE 145 IndiePlex INDIE 909 HSN HSN 12 FSN Prime Ticket ** FSPT 774 Spike TV - West SPKE-W 146 MoreMAX MORMAX 834 KCRA-3 (NBC) KCRA 3 FSN Rocky Mountain ** FSRM 760 SportsNet New York ** SNNY 704 OuterMAX OUTMAX 839 KMAX-31 (THE CW) KMAX 31 FSN South ** FSS 724 SportSouth ** SPTSO 729 RetroPlex RETRO 910 KOVR-13 (CBS) KOVR 13 FSN Southwest ** FSSW 753 Sun Sports ** SUN 722 Showtime SHO 852 KQCA-58 (MY NETWORK TV) KQCA 58 FSN West ** FSW 772 Sundance Channel -

Depressives and the Scenes of Queer Writing

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 10-2014 Depressives and the Scenes of Queer Writing Allen Durgin Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/482 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] DEPRESSIVES & THE SCENES OF QUEER WRITING by ALLEN DURGIN A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in English in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2014 ii © 2014 ALLEN DURGIN All Rights Reserved iii This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in English in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Date Robert Reid-Pharr, Chair of Committee Date Mario DiGangi, Executive Officer Wayne Koestenbaum Steven F. Kruger THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iv ABSTRACT DEPRESSIVES AND THE QUEER SCENES OF WRITING by ALLEN DURGIN Adviser: Professor Robert Reid-Pharr My dissertation attempts to answer the question: What exactly does a reparative reading look like? The question refers to Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick’s provocative essay on paranoid and reparative reading practices, in which Sedgwick describes how the hermeneutics of suspicion has become central to a whole range of intellectual projects across the humanities and social sciences. Criticizing this dominant critical mode for its political blindness and unintended replication of repressive social structures, Sedgwick looks for an alternative in what she calls reparative reading. -

SUMMER 2011 Ccjig.Blogspot.Com Growth of Patch, Indie Sites Shows Citizen Journalism Going Mainstream

CIVIC and CITIZEN Journalism www.has.vcu.edu/civic-journalism INTEREST GROUP NEWS SUMMER 2011 ccjig.blogspot.com Growth of Patch, indie sites shows citizen journalism going mainstream By Jack Rosenberry June. Patch sites were CCJIG Newsletter Editor located in 11 communi- ties in New Jersey and One of the most Connecticut in late The annual convention is the highlight of in- striking recent develop- 2009 but grew to about volvement for AEJMC members, and this news- ments in the world of 100 sites in nine states letter previews CCJIG’s plans including a full online news, and citi- by August 2010 and slate of programming (page 3) and research ses- zen journalism, has approximately 800 sites sions (page 4). Also be sure to attend the mem- been the rapid expan- across 20 states by ber meeting at 6:45 p.m. Thursday Aug. 11 . sion of the Patch.com early 2011. Other convention facts to keep in mind: network of local news These local news Key Dates sites owned by AOL. sites primarily cover “Early Bird” registration deadline: July 8 Patch was started affluent bedroom com- Pre-conference sessions: Tues. Aug. 9 in 2008 by a group that munities that surround Conference: Wed. Aug. 10 to Sat. Aug. 13. included Tim Arm- large cities such as Convention Hotel: strong, a former Google New York City, Los An- The Renaissance St. Louis Grand Hotel, 800 executive. Armstrong geles, Chicago, Atlanta, Washington Ave. joined AOL in early and Washington, DC. Web site 2009, and the company http://www.aejmcstlouis.org/home/ acquired Patch that See PATCH, page 6 Online tools help educators teach selves, students By Sue Ellen Christian tal media as well as teaching the teach both the basic news writ- CCJIG Teaching Chair foundational elements of the ing and reporting and the multi- craft. -

Winter Channel Directory

Winter Channel Directory U100 PACKAGE continued: U200 PACKAGE continued: U100 PAckAge The Weather Channel 225 Urge 31 – Radio Alterna 5131 (with locals) includes: The Word Network 575 Urge 32 – Tejano 5132 A&E 166 TLC 250 Urge 33 – Smooth Jazz 5133 ABC Family 178 TNT ** 108 Urge 34 – Classic Jazz 5134 ABC News Now 243 TNT - West ** 109 Urge 35 – Blues 5135 AMC * 795 Travel Channel 254 Urge 36 – Easy Listening 5136 Animal Planet 252 TruTV 164 Urge 37 – Classical 5137 AT&T Kids Multiview 301 TruTV - West 165 Urge 38 – Christian 5138 AT&T News Multiview 201 TV Awards NEW! 95 Urge 39 – Gospel 5139 AT&T Online Photos from Flickr 91 TV Land 138 Urge 40 – POP Standards 5140 AT&T Sports Multiview 601 Univision * ** 3002 Urge 41 – Jazzup Broadway 5141 AT&T U-verse Buzz 300 USA Network ** 124 Urge 42 – Cinema 5142 AT&T U-verse Call History 9900 VH1 518 Urge 43 – Nick Jr. 5143 AT&T U-verse Customer Notification 400 WGN America ** 180 Urge 44 – Nick Kids 5144 AT&T U-verse Front Row 100 World Harvest Television 578 Urge 45 – Dream Sequence 5145 AT&T U-verse Pay Per View 102 Urge 46 – Swing 5146 AT&T U-verse Shopping 1 84 Urge 47 – Showcase 5147 AT&T U-verse Shopping 2 429 U200 PAckAge Urge 48 – Comedy 5148 AT&T U-verse Sports 600 includes everything in U100, 48 digital VERSUS ** 640 music channels, plus these channels: AT&T U-verse Theatre 200 VH1 Classic 520 AT&T Weather On Demand 227 BBC America 188 WE (Women’s Entertainment) * 372 AT&T Yahoo! Games 92 BIO 272 WE (Women’s Entertainment) - West 373 AT&T YELLOWPAGES.COM TV 97 Bloomberg TV 222 WealthTV 470 BET 155 Boomerang 327 Big Ten Network ** 650 CCTV-9 3602 U200 LAtino PAckAge includes everything in U200, Bravo 181 Chiller 153 plus Paquete Español.