The Challenge to English Boxing Contracts, 6 Marq

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dec 2004 Current List

Fighter Opponent Result / RoundsUnless specifiedDate fights / Time are not ESPN NetworkClassic, Superbouts. Comments Ali Al "Blue" Lewis TKO 11 Superbouts Ali fights his old sparring partner Ali Alfredo Evangelista W 15 Post-fight footage - Ali not in great shape Ali Archie Moore TKO 4 10 min Classic Sports Hi-Lites Only Ali Bob Foster KO 8 21-Nov-1972 ABC Commentary by Cossell - Some break up in picture Ali Bob Foster KO 8 21-Nov-1972 British CC Ali gets cut Ali Brian London TKO 3 B&W Ali in his prime Ali Buster Mathis W 12 Commentary by Cossell - post-fight footage Ali Chuck Wepner KO 15 Classic Sports Ali Cleveland Williams TKO 3 14-Nov-1966 B&W Commentary by Don Dunphy - Ali in his prime Ali Cleveland Williams TKO 3 14-Nov-1966 Classic Sports Ali in his prime Ali Doug Jones W 10 Jones knows how to fight - a tough test for Cassius Ali Earnie Shavers W 15 Brutal battle - Shavers rocks Ali with right hand bombs Ali Ernie Terrell W 15 Feb, 1967 Classic Sports Commentary by Cossell Ali Floyd Patterson i TKO 12 22-Nov-1965 B&W Ali tortures Floyd Ali Floyd Patterson ii TKO 7 Superbouts Commentary by Cossell Ali George Chuvalo i W 15 Classic Sports Ali has his hands full with legendary tough Canadian Ali George Chuvalo ii W 12 Superbouts In shape Ali battles in shape Chuvalo Ali George Foreman KO 8 Pre- & post-fight footage Ali Gorilla Monsoon Wrestling Ali having fun Ali Henry Cooper i TKO 5 Classic Sports Hi-Lites Only Ali Henry Cooper ii TKO 6 Classic Sports Hi-Lites Only - extensive pre-fight Ali Ingemar Johansson Sparring 5 min B&W Silent audio - Sparring footage Ali Jean Pierre Coopman KO 5 Rumor has it happy Pierre drank before the bout Ali Jerry Quarry ii TKO 7 British CC Pre- & post-fight footage Ali Jerry Quarry ii TKO 7 Superbouts Ali at his relaxed best Ali Jerry Quarry i TKO 3 Ali cuts up Quarry Ali Jerry Quarry ii TKO 7 British CC Pre- & post-fight footage Ali Jimmy Ellis TKO 12 Ali beats his old friend and sparring partner Ali Jimmy Young W 15 Ali is out of shape and gets a surprise from Young Ali Joe Bugner i W 12 Incomplete - Missing Rds. -

ANNUAL UCLA FOOTBALL AWARDS Henry R

2005 UCLA FOOTBALL MEDIA GUIDE NON-PUBLISHED SUPPLEMENT UCLA CAREER LEADERS RUSHING PASSING Years TCB TYG YL NYG Avg Years Att Comp TD Yds Pct 1. Gaston Green 1984-87 708 3,884 153 3,731 5.27 1. Cade McNown 1995-98 1,250 694 68 10,708 .555 2. Freeman McNeil 1977-80 605 3,297 102 3,195 5.28 2. Tom Ramsey 1979-82 751 441 50 6,168 .587 3. DeShaun Foster 1998-01 722 3,454 260 3,194 4.42 3. Cory Paus 1999-02 816 439 42 6,877 .538 4. Karim Abdul-Jabbar 1992-95 608 3,341 159 3,182 5.23 4. Drew Olson 2002- 770 422 33 5,334 .548 5. Wendell Tyler 1973-76 526 3,240 59 3,181 6.04 5. Troy Aikman 1987-88 627 406 41 5,298 .648 6. Skip Hicks 1993-94, 96-97 638 3,373 233 3,140 4.92 6. Tommy Maddox 1990-91 670 391 33 5,363 .584 7. Theotis Brown 1976-78 526 2,954 40 2,914 5.54 7. Wayne Cook 1991-94 612 352 34 4,723 .575 8. Kevin Nelson 1980-83 574 2,687 104 2,583 4.50 8. Dennis Dummit 1969-70 552 289 29 4,356 .524 9. Kermit Johnson 1971-73 370 2,551 56 2,495 6.74 9. Gary Beban 1965-67 465 243 23 4,087 .522 10. Kevin Williams 1989-92 418 2,348 133 2,215 5.30 10. Matt Stevens 1983-86 431 231 16 2,931 .536 11. -

Behind the Mask: My Autobiography

Contents 1. List of Illustrations 2. Prologue 3. Introduction 4. 1 King for a Day 5. 2 Destiny’s Child 6. 3 Paris 7. 4 Vested Interests 8. 5 School of Hard Knocks 9. 6 Rolling with the Punches 10. 7 Finding Klitschko 11. 8 The Dark 12. 9 Into the Light 13. 10 Fat Chance 14. 11 Wild Ambition 15. 12 Drawing Power 16. 13 Family Values 17. 14 A New Dawn 18. 15 Bigger than Boxing 19. Illustrations 20. Useful Mental Health Contacts 21. Professional Boxing Record 22. Index About the Author Tyson Fury is the undefeated lineal heavyweight champion of the world. Born and raised in Manchester, Fury weighed just 1lb at birth after being born three months premature. His father John named him after Mike Tyson. From Irish traveller heritage, the“Gypsy King” is undefeated in 28 professional fights, winning 27 with 19 knockouts, and drawing once. His most famous victory came in 2015, when he stunned longtime champion Wladimir Klitschko to win the WBA, IBF and WBO world heavyweight titles. He was forced to vacate the belts because of issues with drugs, alcohol and mental health, and did not fight again for more than two years. Most thought he was done with boxing forever. Until an amazing comeback fight with Deontay Wilder in December 2018. It was an instant classic, ending in a split decision tie. Outside of the ring, Tyson Fury is a mental health ambassador. He donated his million dollar purse from the Deontay Wilder fight to the homeless. This book is dedicated to the cause of mental health awareness. -

Branding Jamaica's Tourism Product

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Masters Theses Student Theses & Publications 2015 Stepping out from the Crowd: (Re)branding Jamaica's Tourism Product through Sports and Culture Thelca Patrice White Eastern Illinois University This research is a product of the graduate program in Communication Studies at Eastern Illinois University. Find out more about the program. Recommended Citation White, Thelca Patrice, "Stepping out from the Crowd: (Re)branding Jamaica's Tourism Product through Sports and Culture" (2015). Masters Theses. 2367. https://thekeep.eiu.edu/theses/2367 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses & Publications at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Graduate School~ U'II'El\.N ILLINOIS UNIVERSITY'" Thesis Maintenance and Reproduction Certificate FOR: Graduate Candidates Completing Theses in Partial Fulfillment of the Degree Graduate Faculty Advisors Directing the Theses RE: Preservation, Reproduction, and Distribution of Thesis Research Preserving, reproducing, and distributing thesis research is an important part of Booth Library's responsibility to provide access to scholarship. In order to further this goal, Booth Library makes all graduate theses completed as part of a degree program at Eastern Illinois University available for personal study, research, and other not-for-profit educational purposes. Under 17 U.S.C. § 108, the library may reproduce and distribute a copy without infringing on copyright; however, professional courtesy dictates that permission be requested from the author before doing so. Your signatures affirm the following: • The graduate candidate is the author of this thesis. -

The Bar Will Shut 20 Minutes Before the Lounge Is Closed So That Customers Have Time to Finish Their Drinks & Take Their Seats for the Main Events

Dear Fight Fan Hospitality Ticket Packages are now on sale for fans to see IBF world featherweight champion Josh Warrington take on his mandatory challeng- er Kid Galahad at the First Direct Arena on June 15th live on BT Sport. Josh will make the second defence of his IBF world featherweight title against mandatory challenger Kid Galahad at the Leeds Arena on June 15th. It will be a hometown return for Warrington in the all Yorkshire grudge match against his old amateur rival Galahad who hails from Shef- field. Warrington, 28, caused a big upset when he outpointed defending champion Lee Selby in front of 25,000 fans at Elland Road, home of his beloved Leeds United last May. In December, he cemented his status as one of the boxing stars of 2018 with a thrilling points win against two- weight world champion, Carl Frampton at Manchester Arena in his maiden defence. Fight Night: June 15th 2019 Venue: First Direct Arena, Arena Way, Leeds, LS2 8BY Promotional Representative on the night: Henry The HOSPITALITY PACKAGE includes: - Top priced seated inner ringside ticket to see Josh Warrington v Kid Galahad headline a fantastic card - Access to the FD Bar hospitality lounge from doors open until approx. 21:00 - Complimentary food & drinks - Souvenir Fight Night Accreditation - A free official fight programme - Merchandise item exclusively for package purchasers - Hospitality Staff on site at all times FD Bar Hospitality Lounge: Drinks included in the free bar: Single measure spirits with mixers, wine, beer, cider, soft drinks & bottled water THE BAR WILL SHUT 20 MINUTES BEFORE THE LOUNGE IS CLOSED SO THAT CUSTOMERS HAVE TIME TO FINISH THEIR DRINKS & TAKE THEIR SEATS FOR THE MAIN EVENTS AS PER BRITISH BOXING BOARD OF CONTROL RULES, CUSTOMERS ARE NOT ALLOWED DRINKS AT RINGSIDE. -

WORLD BOXING ASSOCIATION GILBERTO JESUS MENDOZA PRESIDENT OFFICIAL RATINGS AS of NOVEMBER Based on Results Held from 01St to November 30Th, 2018

2018 Ocean Business Plaza Building, Av. Aquilino de la Guardia and 47 St., 14th Floor, Office 1405 Panama City, Panama Phone: +507 203-7681 www.wbaboxing.com WORLD BOXING ASSOCIATION GILBERTO JESUS MENDOZA PRESIDENT OFFICIAL RATINGS AS OF NOVEMBER Based on results held from 01st to November 30th, 2018 CHAIRMAN VICE CHAIRMAN MIGUEL PRADO SANCHEZ - PANAMA GUSTAVO PADILLA - PANAMA [email protected] [email protected] The WBA President Gilberto Jesus Mendoza has been acting as interim MEMBERS ranking director for the compilation of this ranking. The current GEORGE MARTINEZ - CANADA director Miguel Prado is on a leave of absence for medical reasons. JOSE EMILIO GRAGLIA - ARGENTINA MARIANA BORISOVA - BULGARIA Over 200 Lbs / 200 Lbs / 175 Lbs / HEAVYWEIGHT CRUISERWEIGHT LIGHT HEAVYWEIGHT Over 90.71 Kgs 90.71 Kgs 79.38 Kgs WBA SUPER CHAMPION: ANTHONY JOSHUA GBR WBA SUPER CHAMPION: OLEKSANDR USYK UKR WORLD CHAMPION: MANUEL CHARR * SYR WORLD CHAMPION: BEIBUT SHUMENOV KAZ WORLD CHAMPION: DMITRY BIVOL RUS WBA GOLD CHAMPION: ARSEN GOULAMIRIAN ARM WBC: DEONTAY WILDER WBC: OLEKSANDR USYK WBC: ADONIS STEVENSON IBF: ANTHONY JOSHUA WBO: ANTHONY JOSHUA IBF: OLEKSANDR USYK WBO: OLEKSANDR USYK IBF: ARTUR BETERBIEV WBO: ELEIDER ALVAREZ 1. TREVOR BRYAN INTERIM CHAMP USA 1. YUNIEL DORTICOS CUB 1. BADOU JACK SWE 2. JARRELL MILLER USA 2. ANDREW TABITI USA 2. MARCUS BROWNE USA 3. FRES OQUENDO PUR 3. RYAD MERHY CIV 3. KARO MURAT ARM 4. DILLIAN WHYTE JAM 4. YURY KASHINSKY RUS 4. SULLIVAN BARRERA CUB 5. DERECK CHISORA INT GBR 5. MURAT GASSIEV RUS 5. SHEFAT ISUFI SRB 6. OTTO WALLIN SWE 6. MAKSIM VLASOV RUS 6. -

Boxing Edition

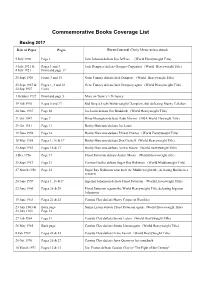

Commemorative Books Coverage List Boxing 2017 Date of Paper Pages Event Covered (Daily Mirror unless stated) 5 July 1910 Page 3 Jack Johnson defeats Jim Jeffries (World Heavyweight Title) 3 July 1921 & Pages 1 and 3 Jack Dempsey defeats Georges Carpentier (World Heavyweight Title) 4 July 1921 Front and page 17 25 Sept 1926 Front, 3 and 15 Gene Tunney defeats Jack Dempsey (World Heavyweight Title) 23 Sept 1927 & Pages 1, 3 and 18 Gene Tunney defeats Jack Dempsey again (World Heavyweight Title) 24 Sep 1927 Front 1 October 1927 Front and page 5 More on Tunney v Dempsey 19 Feb 1930 Pages 5 and 22 Kid Berg is Light Welterweight Champion after defeating Mushy Callahan 24 June 1937 Page 30 Joe Louis defeats Jim Braddock (World Heavyweight Title) 21 Oct 1947 Page 7 Rinty Monaghan defeats Dado Marino (NBA World Flyweight Title) 29 Oct 1951 Page 11 Rocky Marciano defeats Joe Louis 19 June 1954 Page 14 Rocky Marciano defeats Ezzard Charles (World Heavyweight Title) 18 May 1955 Pages 1, 16 & 17 Rocky Marciano defeats Don Cockell (World Heavyweight Title) 23 Sept 1955 Pages 16 & 17 Rocky Marciano defeats Archie Moore (World Heavyweight Title) 3 Dec 1956 Page 17 Floyd Patterson defeats Archie Moore (World Heavyweight title) 25 Sept 1957 Page 23 Carmen Basilio defeats Sugar Ray Robinson (World Middleweight Title) 27 March 1958 Page 23 Sugar Ray Robinson wins back the Middleweight title, defeating Basilio in a rematch 28 June 1959 Pages 1, 16 &17 Ingemar Johansson defeats Floyd Patterson (World Heavyweight Title) 22 June 1960 Pages 28 & 29 Floyd Patterson -

FA 2010 Resource Pack

Frantic Assembly and the National Theatre of Scotland present Beautiful Burnout By Bryony Lavery A Comprehensive Guide for students (aged 14+), teachers & arts educationalists By Scott Graham Contents 3 Introduction 4 Why Boxing? 4 Why Beautiful Burnout? 5 Why Underworld? 5 Why Bryony Lavery? 5 Essays 5 Research and Development 6 The danger of cliché and the need for authenticity 7 Damage: The Elephant in the room 8 Bloodsport or Noble Art? 9 Creating the image 10 The Training 12 The Research - the gyms, lists, DVDs, books, interviews 13 The Warm Ups - Flipping what we know - Explosive before stretches 13 Fathers and Sons - the boxing family 14 The Use of Film 15 The Referee 17 God and Man 17 The Danger of Unison 17 Scenes 17 The Fight - 'Beautiful Burnout' 19 Kittens 19 Wraps 20 Scribble (inc.This Is Your Scribble!) 21 One Punch 22 Catch Up 23 Referees 24 Exercises 24 Head Smacks 24 Trainer and Boxer 25 Bibliography Photos by Gavin Evans Front cover photo by Ela Wlodarczyk Introduction This resource pack is written to enhance the experience of watching Beautiful Burnout, to hopefully give some insight into the creative process and maybe even answer some questions. What you will not find too much of is work sheets and references to examination bodies and attainment targets. The reason behind this is that we hope this pack can be both informative and enjoyable. Teachers know their classes better than we do and can take any inspiration found in here and apply it within the classroom better than we can by suggesting an exercise. -

Boxing, Governance and Western Law

An Outlaw Practice: Boxing, Governance and Western Law Ian J*M. Warren A Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Human Movement, Performance and Recreation Victoria University 2005 FTS THESIS 344.099 WAR 30001008090740 Warren, Ian J. M An outlaw practice : boxing, governance and western law Abstract This investigation examines the uses of Western law to regulate and at times outlaw the sport of boxing. Drawing on a primary sample of two hundred and one reported judicial decisions canvassing the breadth of recognised legal categories, and an allied range fight lore supporting, opposing or critically reviewing the sport's development since the beginning of the nineteenth century, discernible evolutionary trends in Western law, language and modern sport are identified. Emphasis is placed on prominent intersections between public and private legal rules, their enforcement, paternalism and various evolutionary developments in fight culture in recorded English, New Zealand, United States, Australian and Canadian sources. Fower, governance and regulation are explored alongside pertinent ethical, literary and medical debates spanning two hundred years of Western boxing history. & Acknowledgements and Declaration This has been a very solitary endeavour. Thanks are extended to: The School of HMFR and the PGRU @ VU for complete support throughout; Tanuny Gurvits for her sharing final submission angst: best of sporting luck; Feter Mewett, Bob Petersen, Dr Danielle Tyson & Dr Steve Tudor; -

Wbc´S Lightweight World Champions

WORLD BOXING COUNCIL Jose Sulaimán WBC HONORARY POSTHUMOUS LIFETIME PRESIDENT (+) Mauricio Sulaimán WBC PRESIDENT WBC STATS WBC HEAVYWEIGHT CHAMPIONSHIP BOUT BARCLAYS CENTER / BROOKLYN, NEW YORK, USA NOVEMBER 4, 2017 THIS WILL BE THE WBC’S 1, 986 CHAMPIONSHIP TITLE FIGHT IN ITS 54 YEARS OF HISTORY LOU DiBELLA & DiBELLA ENTERTAINMENT, PRESENTS: DEONTAY WILDER (US) BERMANE STIVERNE (HAITI/CAN) WBC CHAMPION WBC Official Challenger (No. 1) Nationality: USA Nationality: Canada Date of Birth: October 22, 1985 Date of Birth: November 1, 1978 Birthplace: Tuscaloosa, Alabama Birthplace: La Plaine, Haiti Alias: The Bronze Bomber Alias: B Ware Resides in: Tuscaloosa, Alabama Resides in: Las Vegas, Nevada Record: 38-0-0, 37 KO’s Record: 25-2-1, 21 KO’s Age: 32 Age: 39 Guard: Orthodox Guard: Orthodox Total rounds: 112 Total rounds: 107 WBC Title fights: 6 (6-0-0) World Title fights: 2 (1-1-0) Manager: Jay Deas Manager: James Prince Promoter: Al Haymon / Lou Dibella Promoter: Don King Productions WBC´S HEAVYWEIGHT WORLD CHAMPIONS NAME PERIODO CHAMPION 1. SONNY LISTON (US) (+) 1963 - 1964 2. MUHAMMAD ALI (US) 1964 – 1967 3. JOE FRAZIER (US) (+) 1968 - 1973 4. GEORGE FOREMAN (US) 1973 - 1974 5. MUHAMMAD ALI (US) * 1974-1978 6. LEON SPINKS (US) 1978 7. KEN NORTON (US) 1977 - 1978 8. LARRY HOLMES (US) 1978 - 1983 9. TIM WITHERSPOON (US) 1984 10. PINKLON THOMAS (US) 1984 - 1985 11. TREVOR BERBICK (CAN) 1986 12. MIKE TYSON (US) 1986 - 1990 13. JAMES DOUGLAS (US) 1990 14. EVANDER HOLYFIELD (US) 1990 - 1992 15. RIDDICK BOWE (US) 1992 16. LENNOX LEWIS (GB) 1993 - 1994 17. -

WBC International Championships

Dear Don José … I will be missing you and I will never forget how much you did for the world of boxing and for me. Mauro Betti The Committee decided to review each weight class and, when possible, declare some titles vacant. The hope is to avoid the stagnation of activities and, on the contrary, ensure to the boxing community a constant activity and the possibility for other boxers to fight for this prestigious belt. The following situation is now up to WEDNESDAY 9 November 2016: Heavy Dillian WHYTE Jamaica Silver Heavy Andrey Rudenko Ukraine Cruiser Constantin Bejenaru Moldova, based in NY USA Lightheavy Joe Smith Jr. USA … great defence on the line next December. Silver LHweight: Sergey Ekimov Russia Supermiddle Michael Rocky Fielding Great Britain Silver Supermiddle Avni Yildirim Turkey Middle Craig CUNNINGHAM Great Britain Silver Middleweight Marcus Morrison GB Superwelter vacant Sergio Garcia relinquished it Welter Sam EGGINGTON Great Britain Superlight Title vacant Cletus Seldin fighting for the vacant belt. Silver 140 Lbs Aik Shakhnazaryan (Armenia-Russia) Light Sean DODD, GB Successful title defence last October 15 Silver 135 Lbs Dante Jardon México Superfeather Martin Joseph Ward GB Silver 130 Lbs Jhonny Gonzalez México Feather Josh WARRINGTON GB Superbantam Sean DAVIS Great Britain Bantam Ryan BURNETT Northern Ireland Superfly Vacant title bout next Friday in the Philippines. Fly Title vacant Lightfly Vacant title bout next week in the Philippines. Minimum Title vacant Mauro Betti WBC Vice President Chairman of WBC International Championships Committee Member of Ratings Committee WBC Board of Governors Rome, Italy Private Phone +39.06.5124160 [email protected] Skype: mauro.betti This rule is absolutely sacred to the Committee WBC International Heavy weight Dillian WHYTE Jamaica WBC # 13 WBC International Heavy weight SILVER champion Ukraine’s Andryi Rudenko won the vacant WBC International Silver belt at Heavyweight last May 6 in Odessa, Ukraine, when he stopped in seven rounds USA’s Mike MOLLO. -

Mccall – OQUENDO IBF INTER CONTINENTAL HEAVYWEIGHT TITLE CLASH TOMORROW NIGHT LIVE on GFL

McCALL – OQUENDO IBF INTER CONTINENTAL HEAVYWEIGHT TITLE CLASH TOMORROW NIGHT LIVE ON GFL CLICK TO ORDER THE FIGHT HOLLYWOOD, FLA/ NEW YORK (December 6, 2010)—TOMORROW night, a crossroads heavyweight fight between former Heavyweight champion Oliver McCall and former world title challenger Fres Oquendo will take place with huge implications for the winner. The bout will headline a card from the beautiful Seminole Hard Rock Hotel and Casino in Hollywood, Florida and will be seen around the world, LIVE on www.gofightlive.tv The bout will be for the IBF Intercontinental Heavyweight championship. The bout plus a full undercard can be seen LIVE at 7pm est. for just $9.99 by clicking: http://www.gofightlive.tv/Events/Fight/Boxing/Tuesday_Night_Fi ghts__McCall_Vs_Oquendo/894 With the consistent uncertainty in the Heavyweight division, the winner of this bout will get a big leg up in being able to once again compete for the Heavyweight championship of the world. McCall has a career that has spanned twenty-five years, has a record of 54-10 with thirty-seven knockouts. McCall has been in the ring with just about every big-time Heavyweight that has competed in the last quarter century as he has shared the ring with former undisputed champion James “Buster” Douglas (L 10); Former Cruiserweight champion Orlin Norris (L 10) ; Former WBA Heavyweight champion Bruce Seldon (TKO 9); former world title challenger Tony Tucker ( L 12) before shocking the world by stopping WBC Heavyweight champion Lennox Lewis with the right hand heard round the world on September 24, 1994. McCall made one defense against the legendary Larry Holmes before dropping the belt to Frank Bruno in Bruno’s homeland of England.